Loren Eiseley facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Loren Corey Eiseley

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Born | September 3, 1907 Lincoln, Nebraska, U.S.

|

| Died | July 9, 1977 (aged 69) Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, U.S.

|

| Nationality | American |

| Alma mater | University of Nebraska, BA/BS (1933) University of Pennsylvania, MA, PhD (1937) |

| Known for | Nature writer, educator, philosopher |

| Awards | 36 honorary degrees; Phi Beta Kappa Award for "Best science book", Darwin's Century |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Anthropology |

| Institutions | University of Pennsylvania |

| Influences | Sir Francis Bacon, Charles Darwin, Ralph Waldo Emerson, Henry David Thoreau, Alfred Russel Wallace |

Loren Eiseley (born September 3, 1907 – died July 9, 1977) was an amazing American scientist, teacher, and writer. He loved to explore big ideas about humans, nature, and the universe. He was an anthropologist (someone who studies human societies and cultures), a philosopher (someone who thinks deeply about life), and a natural science writer.

Eiseley taught and published many books from the 1950s to the 1970s. He received many special awards and was a member of important groups. When he passed away, he was a top professor at the University of Pennsylvania.

He was known as a "scholar and writer of imagination and grace." His work went far beyond the university where he taught for 30 years. Some people even called him "the modern Henry David Thoreau," who was another famous nature writer. Eiseley's writing covered many topics, from the mind of Sir Francis Bacon to the prehistoric origins of man and the ideas of Charles Darwin.

Eiseley became famous mostly because of his books. These include The Immense Journey (1957), Darwin's Century (1958), The Unexpected Universe (1969), The Night Country (1971), and his life story, All the Strange Hours (1975). Science writer Orville Prescott said Eiseley could write "with poetic sensibility and with a fine sense of wonder." Author Mary Ellen Pitts noted that Eiseley combined science and literature, much like naturalists from the 18th and 19th centuries. The famous science fiction writer Ray Bradbury called Eiseley "every writer's writer, and every human's human."

A newspaper called The New York Times said that Eiseley's main message was in his essay The Enchanted Glass. He wrote about the need for a thoughtful naturalist who had time to observe, think, and dream. Before he died, he received awards for helping people understand science and for improving life and the environment.

Contents

Growing Up and Discovering Nature

Eiseley was born in Lincoln, Nebraska. His childhood was not easy. His father worked hard, and his mother was deaf and sometimes struggled with her emotions. Their home was on the edge of town, which made them feel separate from others. Eiseley's autobiography, All the Strange Hours, talks about his childhood as being difficult.

His father, Clyde, was a salesman but also loved acting in Shakespearean plays. He taught Loren to love beautiful language and writing. His mother, Daisey Corey, was an artist who taught herself. She lost her hearing as a child.

Living on the edge of town helped Eiseley become interested in nature. He would play in nearby caves and creek banks when things were tough at home. His half-brother, Leo, gave him a copy of Robinson Crusoe, which helped him teach himself to read. After that, he often went to the public library and became a huge reader.

Eiseley went to school in Lincoln. In high school, he knew he wanted to be a nature writer. He described the lands around Lincoln as "flat and grass-covered and smiling so serenely up at the sun." But because of his home life and his father's illness and death, he left school for a while and took odd jobs.

He later enrolled at the University of Nebraska. There, he wrote for a new journal called Prairie Schooner. He also went on archaeology digs for the school's natural history museum, Morrill Hall. In 1927, he got sick with tuberculosis. He left the university and moved to the western desert, hoping the dry air would help him. He soon felt restless and traveled around the country by hopping on freight trains, like many people did during the Great Depression. A professor named Richard Wentz wrote that Eiseley explored his soul as he searched for the past. He became a naturalist and a "bone hunter" because the landscape connected his mind to life and death.

His Journey as a Scientist and Teacher

Eiseley eventually returned to the University of Nebraska. He earned degrees in English and Geology/Anthropology. He was the editor of The Prairie Schooner magazine and published his own poems and stories. His trips to hunt for fossils and human artifacts in Nebraska and the southwest inspired much of his early work. He later said he came to anthropology from studying old bones, and he preferred to leave ancient human burial sites alone unless they were in danger.

Eiseley earned his highest degree, a Ph.D., from the University of Pennsylvania in 1937. His research focused on understanding ancient times, which started his career in academics. He began teaching at the University of Kansas that same year. During World War II, he taught anatomy to students preparing for medical school.

In 1944, he became the head of the Sociology and Anthropology Department at Oberlin College. In 1947, he returned to the University of Pennsylvania to lead its anthropology department. He was chosen as president of the American Institute of Human Paleontology in 1949. From 1959 to 1961, he was a top leader at the University of Pennsylvania. In 1961, the university created a special teaching position just for him.

Eiseley was also a member of many important groups, including the American Association for the Advancement of Science.

When he died in 1977, he was still a special professor at the University of Pennsylvania. He had received 36 special degrees over 20 years, making him one of the most honored people at the university since Benjamin Franklin. In 1976, he won awards for helping the public understand science and for improving the environment.

Amazing Books by Loren Eiseley

Besides his scientific work, Eiseley started writing essays in the mid-1940s that reached many people. He wrote different types of books, including poetry, autobiography (his life story), science history, and essays. In all his writing, he used a poetic style. His writing was special because he could explain complex ideas about human origins and our connection to nature to people who weren't scientists. Robert G. Franke said Eiseley's essays were like plays, perhaps influenced by his father's acting hobby.

Why He Wrote

Richard Wentz, a professor, explained that for Eiseley, writing was a way of thinking deeply. He said Eiseley had a special way of making readers feel like they were on a journey into the universe with him. He could explain history or the ideas of scientists and philosophers in a very personal way.

However, because Eiseley's writing was so intense and poetic, and he focused on nature and the universe, some of his fellow scientists didn't always understand him. A friend once told him, "You are a freak... You like scholarship, but the scholars... are not going to like you because you don't stay in the hole where God supposedly put you."

Books from the 1950s

- The Immense Journey (1957)

This was Eiseley's first book, a collection of writings about human history. It was a rare science book that many people loved. It sold over a million copies and was translated into at least 16 languages. This book made him famous as a writer who could mix science and humanity in a beautiful, poetic way.

In the book, Eiseley shares his wonder at how long time has passed and how huge the universe is. He uses his own experiences and thoughts about ancient fossils to talk about evolution. He especially focuses on human evolution and how much we still don't know.

- Darwin's Century (1958)

The full title of this book is "Evolution and the Men Who Discovered It." Eiseley showed that people had been observing animal changes, extinctions, and Earth's long history since the 1600s. Scientists were trying to understand evolution even before Charles Darwin published On the Origin of Species.

Naturalist Mary Ellen Pitts said that in Darwin's Century, Eiseley looked at the history of evolutionary ideas. He saw that science had made nature seem separate from humans, like a machine. Eiseley believed that this way of thinking had big effects on humankind. He wanted to re-examine science and how we understand it.

In his conclusion, Eiseley quoted Darwin, who said that if we let our imaginations run wild, all animals might share a common ancestor with us. Eiseley added that even if Darwin hadn't come up with natural selection, his words about our connection to animals were incredibly insightful.

This book won a special award for the best science book in 1958.

Books from the 1960s

- The Firmament of Time (1960)

This book explores how humans in the 1960s, with all their scientific knowledge, can find hope and confidence in the new world science has created. A review in The New Yorker said Eiseley "describes with zest and admiration the giant steps that have led man... to grasp the nature of his extraordinary past." It called the book "an irresistible inducement to partake of the almost forgotten excitements of reflection."

The Firmament of Time won the John Burroughs Medal in 1961 for the best nature writing book.

- The Unexpected Universe (1969)

The poet W.H. Auden said that the main idea of The Unexpected Universe is about humans as heroes on a quest. We are wanderers, voyagers, always searching for adventure, knowledge, and meaning. Eiseley wrote in the book:

Every time we walk along a beach some ancient urge disturbs us so that we find ourselves shedding shoes and garments or scavenging among seaweed and whitened timbers like the homesick refugees of a long war ... Mostly the animals understand their roles, but man, by comparison, seems troubled by a message that, it is often said, he cannot quite remember or has gotten wrong ... Bereft of instinct, he must search continually for meanings ... Man was a reader before he became a writer, a reader of what Coleridge once called the mighty alphabet of the universe.

Books from the 1970s

- The Invisible Pyramid (1971)

This book explores inner and outer space, the vastness of the universe, and the limits of what we can know. Eiseley connects past and present civilizations, different universes, humans, and nature. He brings poetic ideas to scientific topics.

He wrote:

Man would not be man if his dreams did not exceed his grasp. ... Like John Donne, man lies in a close prison, yet it is dear to him. Like Donne's, his thoughts at times overleap the sun and pace beyond the body. If I term humanity a slime mold organism it is because our present environment suggest it. If I remember the sunflower forest it is because from its hidden reaches man arose. The green world is his sacred center. In moments of sanity he must still seek refuge there. ... If I dream by contrast of the eventual drift of the star voyagers through the dilated time of the universe, it is because I have seen thistledown off to new worlds and am at heart a voyager who, in this modern time, still yearns for the lost country of his birth.

- The Night Country (1971)

This book is like a journey where Eiseley talks with nature and evolution. Time Magazine said, "Eiseley has met strange creatures in the night country, and he tells marvelous stories about them... For Eiseley, storytelling is never pure entertainment. The autobiographical tales keep illustrating the theses that wind through all his writing – the fallibility of science, the mystery of evolution, the surprise of life."

An alumnus of the University of Pennsylvania, Carl Hoffman, said that The Night Country was his favorite book. Eiseley wrote in it, "It is thus that one day and the next are welded together, and that one night's dying becomes tomorrow's birth. I, who do not sleep, can tell you this."

- All the Strange Hours: The Excavation of a Life (1975)

In this book, Eiseley looks back at his own life. He tells his story with modesty, grace, and a sharp eye for interesting details. He starts with his childhood, which he describes as difficult. From there, he traces his journey that led him to search for early humans and into deep philosophical thinking. He became world-famous, but he felt uneasy about it. Eiseley creates a fascinating self-portrait of a man who thought deeply about his place in society and humanity's place in the natural world.

- The Star Thrower (1978)

His friend, science fiction author Ray Bradbury, said, "The book will be read and cherished in the year 2001. It will go to the Moon and Mars with future generations. Loren Eiseley's work changed my life."

- Darwin and the Mysterious Mr. X (1979)

This book tries to solve a mystery about Charles Darwin. It looks at a disagreement Darwin had with Samuel Butler about who first came up with certain ideas. Eiseley gives credit to Edward Blyth, a naturalist from the 1800s, for developing the idea and even the words "natural selection." Eiseley believed Darwin took these ideas and expanded on them. However, many experts on Darwin, like Stephen Jay Gould, disagreed with Eiseley's conclusions.

Books Published After His Death

- The Lost Notebooks of Loren Eiseley (1987)

Before he died, Eiseley asked his wife to destroy his personal notebooks. But she decided to take them apart instead so they couldn't be used easily. Later, his friend Kenneth Heuer worked hard to put most of them back together. The Lost Notebooks of Loren Eiseley includes many of Eiseley's writings, like childhood stories, sketches from when he traveled, old family pictures, poems he never published, parts of unfinished novels, and letters from famous writers like W.H. Auden and Ray Bradbury.

Eiseley's Big Ideas

Thoughts on Religion

Richard Wentz, a professor of religious studies, said that Eiseley didn't openly say he was religious, but he cared deeply about things that are historically linked to religion. Wentz believed that Eiseley was like Ralph Waldo Emerson and Henry David Thoreau, who were thinkers and writers who saw their observations of the universe as a form of deep thought.

Wentz quoted Eiseley to show that he was indeed a religious thinker:

I am treading deeper and deeper into leaves and silence. I see more faces watching, non-human faces. Ironically, I who profess no religion find the whole of my life a religious pilgrimage.

The religious forms of the present leave me unmoved. My eye is round, open, and undomesticated as an owl's in a primeval forest – a world that for me has never truly departed.

Like the toad in my shirt we were in the hands of God, but we could not feel him; he was beyond us, totally and terribly beyond our limited- senses.

Man is not as other creatures and ... without the sense of the holy, without compassion, his brain can become a gray stalking horror – the deviser of Belsen.

Wentz concluded that Eiseley was a scientist, but his essays also showed his constant thinking about the deepest meaning of the universe. Science writer Connie Barlow said Eiseley wrote beautiful books from a viewpoint that today would be called Religious Naturalism, which combines science and spiritual ideas.

Thoughts on Evolution

Wentz said that Loren Eiseley was very much like Henry David Thoreau. He used everyday situations to ask new questions and search for meaning in the unknown. He quoted Eiseley from The Star Thrower: "We are, in actuality, students of that greater order known as nature. It is into nature that man vanishes."

Eiseley often wrote that humans don't have enough proof to know exactly how we came to be. In The Immense Journey, he wrote, "... many lines of seeming relatives, rather than merely one, lead to man. It is as though we stood at the heart of a maze and no longer remembered how we had come there." According to Wentz, Eiseley realized that some things cannot truly be explained, like "the necessity of life" or "the hunger of the elements to become life." He felt that the human story of evolution might be "too simplistic for belief."

Thoughts on Science and Progress

Eiseley talked about the idea that science might create illusions in his book, The Firmament of Time:

A scientist writing around the turn of the century remarked that all of the past generations of men have lived and died in a world of illusion. The unconscious irony in his observation consists in the fact that this man assumed the progress of science to have been so great that a clear vision of the world without illusion was, by his own time, possible. It is needless to add that he wrote before Einstein ... at a time when Mendel was just about to be rediscovered, and before the advances in the study of radioactivity ...

Wentz noted Eiseley's belief that science might have lost its way. Eiseley thought that much of modern science had moved humanity further away from its responsibility to the natural world. He believed that we had created an artificial world to satisfy our endless desires. Wentz added that Eiseley told us it would be good to listen to the message of the Buddha, who knew that "one cannot proceed upon the path of human transcendence until one has made interiorly in one's soul a road into the future."

Purpose for Humankind

Wentz wrote that Eiseley, like a shaman or spiritual master, shared his healing vision with those who felt lost. He believed we must learn to see again and find the true center of ourselves in the "otherness of nature."

Later Life and Legacy

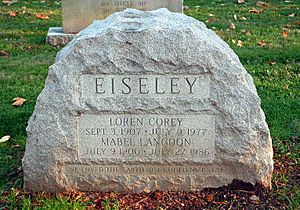

Loren Eiseley passed away on July 9, 1977, after surgery. He was buried in West Laurel Hill Cemetery in Bala Cynwyd, Pennsylvania. His wife, Mabel Langdon Eiseley, is buried next to him. The words on their headstone say, "We loved the earth but could not stay," which is a line from one of his poems.

A library in Lincoln, Nebraska, is named after Eiseley. He also received the Distinguished Nebraskan Award and was added to the Nebraska Hall of Fame. A statue of him is in the Nebraska State Capitol.

Eiseley is still considered a very important nature writer. He explored human life and mind against the background of our universe. He was able to connect science, natural history, and poetry with grace and ease. His writing explained science to non-scientists using beautiful language, stories, and comparisons, making it feel like a good mystery.

On October 25, 2007, the Governor of Nebraska, Dave Heineman, declared that year "The Centennial Year of Loren Eiseley." He encouraged everyone in Nebraska to read Eiseley's writings and appreciate his rich language, his ability to show the long passage of time, and his concern for the future of all living things.

See also

In Spanish: Loren Eiseley para niños

In Spanish: Loren Eiseley para niños

- American philosophy

- List of American philosophers

- Ian McHarg

| Anna J. Cooper |

| Mary McLeod Bethune |

| Lillie Mae Bradford |