Luray Caverns facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Luray Caverns |

|

|---|---|

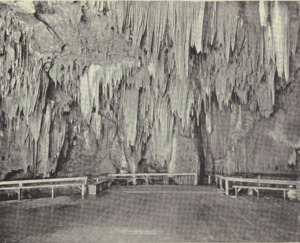

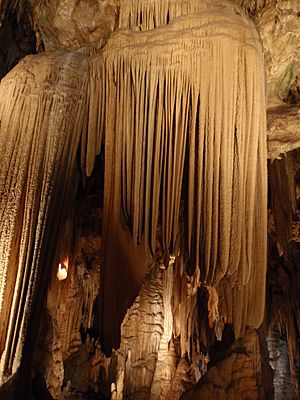

Stalactites, stalagmites and columns in Luray Caverns

|

|

| Lua error in Module:Location_map at line 420: attempt to index field 'wikibase' (a nil value). | |

| Location | Luray, Virginia |

| Designated | 1973 |

Luray Caverns, once called Luray Cave, is a famous cave located near Luray, Virginia, in the United States. Many people have visited it since it was found in 1878.

The cave system is filled with amazing rock formations called speleothems. These include columns, stalactites (hanging from the ceiling), stalagmites (growing from the floor), flowstone (like frozen waterfalls), and pools that look like mirrors.

Luray Caverns is also home to the Great Stalacpipe Organ. This is a special musical instrument that uses solenoids (electric devices) to gently tap different sized stalactites. Each tap makes a sound, like a xylophone or bell.

In 1880, a report from the Smithsonian Institution said that Luray Caverns was probably one of the most beautifully decorated caves in the world.

The Graves family owns Luray Caverns. They have lived in Luray for many years. Theodore Clay Northcott, who was the great-grandfather of the current owners, bought the land where the caverns are in 1905.

Contents

Exploring Luray Caverns

When you visit Luray Caverns, you walk along a path that goes down into the cave. You will see beautiful spots like Dream Lake, The Saracen's Tent, and the Great Stalacpipe Organ. There are also many large stalactites and stalagmites to admire.

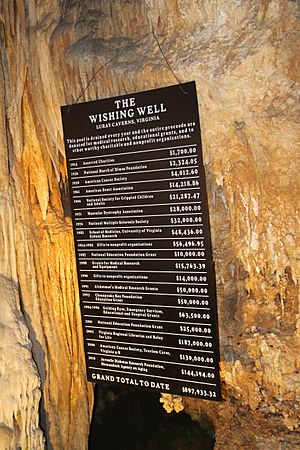

The path continues to the Wishing Well and a special memorial for veterans from Page County. Then, you go up through a small passage past a rock formation called the Fried Eggs. Finally, you return to the entrance.

The whole walk is about 1.5 miles (2.4 km) long. It usually takes between 45 minutes to 1 hour to complete. You can bring small pets on the cave tour. Leashed pets are also allowed on the grounds outside the cave.

The caverns now have a path with no steps, which makes it easier to get around. This path allows wheelchairs, but the caverns are not fully advertised as being accessible for everyone.

History of the Caverns

How Luray Caverns Was Found

Luray Caverns was discovered on August 13, 1878. Five local men found it. They were Andrew J. Campbell (a local tinsmith, who worked with metal), William Campbell, John “Quint” Campbell, and a photographer named Benton Stebbins.

The men noticed a piece of limestone sticking out of the ground. They also felt cool air coming from a nearby sinkhole (a hole in the ground). They thought there might be a cave, so they started digging.

About four hours later, they made a hole big enough for the smallest men, Andrew and Quint, to squeeze through. They slid down a rope and explored the cave with candles. The first large rock column they saw was named the Washington Column, after the first U.S. President.

In an area called Skeleton's Gorge, they found old bone pieces and other items stuck in the rock. They also found pieces of charcoal, flint, and human bone fragments. A skeleton, believed to be from a Native American girl, was found in one of the deep cracks. Experts thought it was about 500 years old. It is believed her remains might have fallen into the cave if her burial spot collapsed.

Ownership and Fame

The land where the cave was found belonged to Sam Buracker. Because of money problems, his land was sold at an auction on September 14, 1878. Andrew Campbell, William Campbell, and Benton Stebbins bought the land where the cave was. They kept their discovery a secret until after the sale.

Because the true value of the cave was not known until after the purchase, there were legal arguments for the next two years. People tried to prove that the sale was unfair. In April 1881, the Supreme Court of Virginia canceled the purchase by the cave discoverers. Eventually, the property was sold to the Luray Caverns Company in 1893. This company, owned by J. Kemp Bartlett, still owns the caverns today.

Even with the legal problems, news of the amazing cave spread quickly. Famous people, like Arctic explorer Professor Jerome J. Collins, visited. The Smithsonian Institution sent nine scientists to study the cave. The Encyclopædia Britannica even wrote a long article about its wonders. Alexander J. Brand, Jr., a writer for the New York Times, was the first travel writer to visit and make the caverns popular.

The Limair Sanatorium

In 1901, Colonel Theodore Clay Northcott, who was the president of the Luray Caverns Corporation, built the Limair Sanatorium on top of Cave Hill. He used the cool, clean air from Luray Caverns to cool the rooms of the sanatorium. A sanatorium is a place where people go to get better from illnesses.

Colonel Northcott said it was the first air-conditioned home in the United States. Even on the hottest summer days, the house stayed cool at about 70°F (21°C). He did this by digging a 5-foot (1.5 m) wide shaft down to a cave chamber. He installed a large fan that could change the air in the whole house every four minutes.

Tests showed that the air was very pure, which was thought to help people with breathing problems. This pure air came from the cave, where it was naturally filtered as it moved through cracks in the rocks and over clear springs and pools. The original "Limair" building burned down, but it was rebuilt with bricks.

Luray Caverns Today

Parts of the caverns are open to the public and have been lit with electricity for a long time. In 1906, about 18,000 people visited. By 2018, around 500,000 guests visited each year.

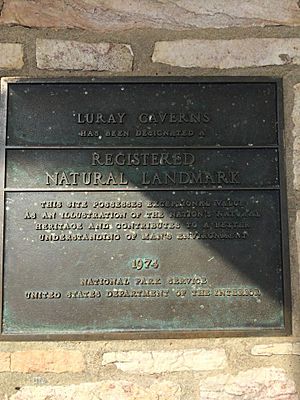

In 1974, the National Park Service and the Department of the Interior named Luray Caverns a National Natural Landmark. This means it is a very special natural place.

Luray Caverns also has a commercial rope course and a fun hedge maze. The maze has 1,500 dark American arborvitae trees that create a 0.5-mile (0.8 km) path for visitors.

Three museums are also on site, and your general admission ticket includes them.

- The Toy Town Junction Museum has many old miniature trains, dolls, and other collectible toys.

- The Car and Carriage Caravan Museum shows over 140 items related to early transportation. This includes a Conestoga wagon and an 1892 Mercedes-Benz car.

- The Shenandoah Heritage Village has old buildings from the 1800s that show what life was like in the Shenandoah Valley.

- The Luray Valley Museum has many important items from the region, like a 1536 Zürich Bible and a special butter churn powered by a dog.

Geology of the Cave

Luray Caverns is located in the Shenandoah Valley, west of the Blue Ridge Mountains. These mountains are part of the Appalachian Mountains in Luray, Virginia. The valley stretches from northeast to southwest along the northwest side of the Blue Ridge.

Cave Hill, which is 927 feet (283 m) above sea level, has always been interesting because of its pits and sinkholes. The people who discovered Luray Caverns entered through one of these sinkholes.

Luray Caverns formed in dolomite rock. At one time, the cave chambers were completely filled with water that had a lot of acid in it. This acid slowly ate away at the softer parts of the rock, forming the walls, ceilings, and floors. One area, called Elfin Ramble, clearly shows where the water levels changed over time.

The temperature inside the caverns stays the same all year, at 54°F (12°C). This is similar to the temperature in Mammoth Cave in Kentucky.

How Cave Formations Grow

Like other limestone caves, the formations at Luray Caverns are made when water with calcium carbonate in it loses some of its carbon dioxide. This causes lime to form. It starts as a thin ring of calcite crystals. Over time, more layers build up, creating stalactites and other types of dripstone and flowstone.

The formations in Luray Caverns are white if the calcium carbonate is pure. Other colors come from impurities in the calcite, which are absorbed from the soil or rock layers.

- Reds and yellows come from iron and iron-stained clays.

- Black comes from manganese dioxide.

- Blues and greens come from copper compounds.

Luray Caverns is still an active cave. New formations grow at a rate of about 1 cubic inch (16 cubic cm) every 120 years.

Famous Cave Formations

After the water level dropped, the eroded shapes remained, and new formations like stalactites, stalagmites, and columns began to grow. Some famous formations include:

- The Leaning Column, which leans like the famous tower in Pisa, Italy.

- The Great Stalacpipe Organ, a large shield-shaped formation that has been used as a musical instrument for many years.

- A huge area of broken carbonates in a space called the Elfin Ramble, left behind by the water.

The cave formations can be yellow, brown, or red because of water, chemicals, and minerals. Newer stalactites growing from older ones are usually white, but sometimes pink or amber. The Empress Column is a rose-colored stalagmite, 35 feet (11 m) high, with many layers. The Double Column, named after Professors Henry and Baird, has two fluted pillars side by side. One is 25 feet (7.6 m) high, and the other is 60 feet (18 m) high. Several stalactites in Giant's Hall are over 50 feet (15 m) long. The Pluto's Ghost is a ghostly white pillar.

The cascades look like foamy waterfalls frozen in mid-air and turned into white or amber rock. Brands Cascade is 40 feet (12 m) high and 30 feet (9.1 m) wide, and it is a waxy white color.

Flowstone draperies are common throughout the cave. One of the best examples is Saracen's Tent. These drapery formations can be found in all the main rooms. They make a bell-like sound when you tap them. They form when water trickles down a sloped, bumpy surface, leaving behind carbonates. In Hoveys Balcony, there are sixteen of these alabaster scarfs hanging side by side. Three are white and thin, and thirteen have stripes like agate with different shades of brown.

There are no true streams or springs in the cave, but there are hundreds of basins. Some are 50 feet (15 m) wide and up to 15 feet (4.6 m) deep. The water in these basins contains lime carbonate, which often forms round shapes called pearls, eggs, and snowballs. Inside, these round growths have a radiating pattern.

Calcite crystals line the sides and bottom of water-filled areas. Changes in water level over time are marked by rings and ridges. These are very clear around Broaddus Lake and the curved walls of the Castles on the Rhine. Here, you can also see polished stalagmites that are buff-colored with white stripes. Others look like huge mushrooms with a velvety coat of red, purple, or olive-colored crystals. In some smaller basins, when the extra carbonate acid escapes quickly, a film forms on the surface, like a sheet of ice. One pool, 12 feet (3.7 m) wide, is covered this way, so you can only see about a third of its surface.

The amount of water in the cavern changes a lot during different seasons. Because of this, some stalactites have their tips underwater long enough for crystals to grow on them. In drier seasons, these crystals get covered again with stalactite material, creating unusual shapes. Nearby stalactites often grow together until they become almost round. If you cut them open, you can see the original tubes inside. Twisted stalactites can be caused by crystals growing sideways, air currents, or a tiny fungus found only in the cave.

It is hard to say the exact size of the chambers in Luray Caverns because they are so uneven. There are several levels of passages, and the total vertical depth from the highest to the lowest point is 260 feet (79 m).

Luray Cavern Waters

There is a spring called Dream Lake that looks almost like a mirror. Stalactites are reflected in the water, making them look like stalagmites growing from below. This illusion is so good that people often cannot see the real bottom. It looks very deep because the stalactites are high above the water, but at its deepest point, the water is only about 20 inches (51 cm) deep. The lake is connected to a spring that goes deeper into the caverns.

The Wishing Well is a green pond with coins at the bottom. It is about 3 feet (0.9 m) deep. Like Dream Lake, the well also creates an illusion, but it is the opposite. The pond looks 3 to 4 feet (90 to 120 cm) deep, but at its deepest point, it is actually 6 to 7 feet (1.8 to 2.1 m) deep.

See also

| DeHart Hubbard |

| Wilma Rudolph |

| Jesse Owens |

| Jackie Joyner-Kersee |

| Major Taylor |