McMahon–Hussein Correspondence facts for kids

The McMahon–Hussein Correspondence was a series of letters exchanged during World War I. In these letters, the British government promised to support Arab independence in a large area after the war. In return, the Sharif of Mecca (a leader of the Arabs) would start the Arab Revolt against the Ottoman Empire. This exchange of letters greatly influenced the Middle East during and after the war. A disagreement about Palestine continued for many years because of these letters.

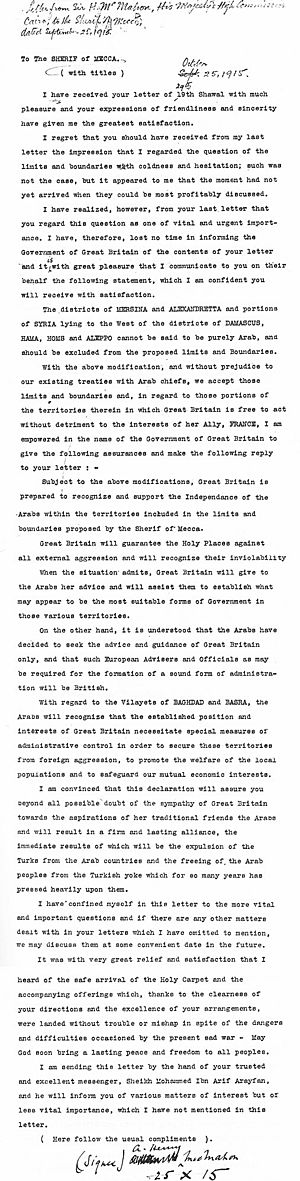

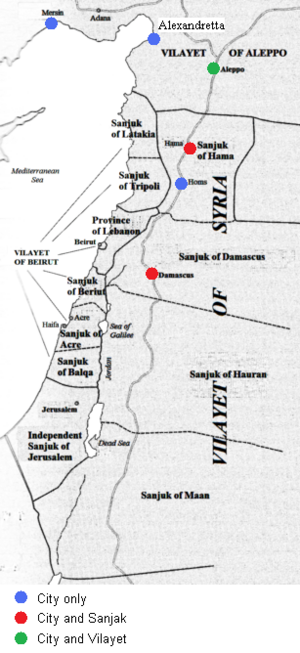

The correspondence includes ten letters sent between July 1915 and March 1916. They were exchanged by Hussein bin Ali, Sharif of Mecca and Sir Henry McMahon, who was the top British official in Egypt. The British wanted Arab help to fight the Ottomans. They also wanted to prevent the Ottoman Empire's call for a "holy war" from turning the many Muslims in British India against them. The area promised for Arab independence was described as "within the limits and boundaries proposed by the Sherif of Mecca". However, some parts of Syria were excluded. These were areas west of Damascus, Homs, Hama, and Aleppo. Different ideas about this description caused big problems later on. One major disagreement, which still exists today, is about how much of the coastal area was meant to be excluded.

Later, in November 1917, the Balfour Declaration was published. This letter promised a national home for Jewish people in Palestine. Then, a secret agreement from 1916, called the Sykes–Picot Agreement, was leaked. This agreement showed that Britain and France planned to divide and control parts of the land promised to the Arabs. Because of these, the Sharif and other Arab leaders felt that the promises made in the McMahon–Hussein Correspondence had been broken. Hussein refused to sign the 1919 Treaty of Versailles. In 1921, when Britain suggested a treaty to accept their control over these areas, Hussein said he couldn't agree to a document that gave Palestine to Zionists and Syria to foreign powers. Another British attempt to make a treaty failed in 1923–24. Within six months, the British stopped supporting Hussein. Instead, they supported their ally Ibn Saud in central Arabia, who then took over Hussein's kingdom.

The correspondence "haunted Anglo-Arab relations" for many years. Parts of the letters were published in newspapers in 1923 and in the 1937 Peel Commission Report. The full correspondence was officially published in 1939. More documents were made public in 1964.

Contents

Why the Letters Were Written

Early Talks About Independence

The first talks between the UK and the Hashemites (Hussein's family) happened in February 1914. This was five months before World War I started. The discussions were between Lord Kitchener, a British official in Egypt, and Abdullah bin al-Hussein, Hussein's second son. Hussein was worried about the new Ottoman governor in his region.

These talks led to a message from Kitchener to Hussein in November 1914. Kitchener, who was now the Secretary of War, promised that Great Britain would "guarantee the independence, rights and privileges of the Sharifate" if the Arabs of Hejaz supported them. Hussein said he couldn't break with the Ottomans right away. But when the Ottomans joined Germany in World War I in November 1914, Britain's interest in an Arab revolt grew quickly. Some historians believe that Britain's failure in a battle called Gallipoli made them even more eager to make a deal with the Arabs.

What Was the Damascus Protocol?

On May 23, 1915, Faisal bin Hussein, Hussein's third son, received a document known as the Damascus Protocol. Faisal was in Damascus to talk with Arab secret groups. The document said that the Arabs would revolt with the United Kingdom. In return, the UK would recognize Arab independence in a large area. This area would stretch from the 37th parallel (a line of latitude) near the Taurus Mountains in the north, to Persia and the Persian Gulf in the east, the Mediterranean Sea in the west, and the Arabian Sea in the south.

The Letters: July 1915 to March 1916

After discussions among Hussein and his sons in June 1915, Hussein decided to write to Sir Henry McMahon. Between July 14, 1915, and March 10, 1916, ten letters were exchanged. McMahon was in touch with Edward Grey, the British Foreign Secretary, who approved the correspondence.

Some historians point to a private letter from McMahon in December 1915 as a sign of possible British dishonesty. In it, McMahon wrote that he didn't take the idea of a "strong united independent Arab State" too seriously. He felt that the situation was "too nebulous" and that their main goal was to "tempt the Arab people into the right path" and get them to join the British side. He suggested using "persuasive terms" rather than arguing over conditions.

Here's a summary of the ten letters:

| No. | From, To, Date | Summary |

|---|---|---|

| 1. | Hussein to McMahon, 14 Jul 1915 |

Boundaries: Asked England to recognize Arab independence in an area from Mersina and Adana in the north, to Persia and the Persian Gulf in the east, the Indian Ocean in the south (except Aden), and the Red Sea and Mediterranean Sea in the west. This was similar to the Damascus Protocol. Caliphate: Asked England to approve an Arab leader for Islam. |

| 2. | McMahon to Hussein, 30 Aug 1915 |

Confirmed British desire for Arab independence and approval of an Arab leader for Islam. |

| 3. | Hussein to McMahon, 9 Sep 1915 |

Repeated that agreeing on the "limits and boundaries" was very important for the talks. |

| 4. | McMahon to Hussein, 24 Oct 1915 |

Boundaries: Agreed on the importance of limits. Said that Mersina, Alexandretta, and parts of Syria west of Damascus, Homs, Hama, and Aleppo were not purely Arab and should be excluded. Stated that Britain would support Arab independence in other areas, as long as it didn't harm France's interests. Other: Promised to protect Holy Places and offer advice to the Arab government. Also mentioned special arrangements for Britain in Baghdad and Basra. |

| 5. | Hussein to McMahon, 5 Nov 1915 |

"Vilayets of Mersina and Adana": Agreed to give up on including these. "[T]wo Vilayets of Aleppo and Beirut and their seacoasts": Refused to exclude these, saying they were purely Arab. |

| 6. | McMahon to Hussein, 14 Dec 1915 |

"Vilayets of Mersina and Adana": Acknowledged agreement. "Vilayets of Aleppo and Beirut": Said this needed "careful consideration" due to France's interests and would be discussed later. |

| 7. | Hussein to McMahon, 1 Jan 1916 |

"Iraq": Proposed to agree on payment after the war. "[T]he northern parts and their coasts": Refused any more changes, saying no land in those regions could be given to France or any other power. |

| 8. | McMahon to Hussein, 25 Jan 1916 |

Acknowledged Hussein's previous points. |

| 9. | Hussein to McMahon, 18 Feb 1916 |

Discussed early plans for the revolt. Asked McMahon for £50,000 in gold, plus weapons, ammunition, and food. |

| 10. | McMahon to Hussein, 10 Mar 1916 |

Discussed early plans for the revolt. Confirmed British agreement to the requests. The Sharif set a possible date for the revolt in June 1916. |

Were These Letters a Treaty?

Some historians, like Elie Kedourie, said the October letter was not a treaty. He also argued that Hussein didn't keep his promises. But Victor Kattan called the correspondence a "secret treaty." He said the UK government treated it as a treaty during the 1919 Paris Peace Conference.

The Arab Revolt: 1916 to 1918

The Arabs saw McMahon's promises as a formal agreement with the United Kingdom. British Prime Minister David Lloyd George and Foreign Secretary Arthur Balfour also called it a treaty during post-war talks. Because of this understanding, the Arabs, led by Hussein's son Faisal, formed a military force. They fought against the Ottoman Empire during the Arab Revolt, with help from T. E. Lawrence (known as "Lawrence of Arabia").

In June 1916, the Arab Revolt began. An Arab army attacked Ottoman forces. They helped capture Aqabah and cut the Hejaz railway, an important link from Damascus to Medina. Meanwhile, the British army, led by General Allenby, moved into Palestine and Syria. The British advance ended with the Battle of Megiddo in September 1918. The Ottoman Empire surrendered on October 31, 1918.

Historians see the Arab revolt as the first organized movement of Arab nationalism. It brought Arab groups together to fight for independence from the Ottoman Empire. After the war, the revolt had lasting effects. The Hashemite kingdom in Jordan is still influenced by the actions of Arab leaders in the revolt.

Other Agreements: 1916 to 1918

The Sykes–Picot Agreement

The Sykes–Picot Agreement was a secret deal between the UK and France. It was agreed upon in January 1916. The French government knew about Britain's letters to Hussein in December 1915, but they didn't know formal promises had been made.

This agreement was revealed in December 1917 by the Bolsheviks after the Russian Revolution. It showed that Britain and France planned to divide and control parts of the promised Arab land. Hussein was told by British officials that the British promises to the Arabs were still valid and that the Sykes–Picot Agreement was not a formal treaty. After the Sykes-Picot Agreement became public, McMahon resigned.

Many sources say the Sykes-Picot Agreement went against the Hussein–McMahon Correspondence. For example, Persia was placed in the British area. Also, British and French advisors would control the area meant for an Arab State. While the correspondence didn't mention Palestine, Haifa and Acre were to be British, and a smaller Palestine area was to be controlled internationally.

The Balfour Declaration

In 1917, the UK issued the Balfour Declaration. This promised to support a national home for Jewish people in Palestine. Historians often look at this declaration, the McMahon-Hussein correspondence, and the Sykes-Picot agreement together. This is because they might not all fit together, especially regarding Palestine. According to Albert Hourani, a historian, these agreements were meant to have "more than one interpretation."

The Hogarth Message

Hussein asked for an explanation of the Balfour Declaration. In January 1918, David George Hogarth, a British official, was sent to deliver a letter to Hussein, who was now King of Hejaz. The Hogarth message assured Hussein that "the Arab race shall be given full opportunity of once again forming a nation in the world." It also mentioned the "freedom of the existing population both economic and political." Hogarth reported that Hussein "would not accept an independent Jewish State in Palestine."

The Declaration to the Seven

Because of the McMahon–Hussein correspondence, the Balfour Declaration, and the Sykes–Picot Agreement, seven Syrian leaders in Cairo asked the UK government for clear answers. They wanted a "guarantee of the ultimate independence of Arabia." In response, on June 16, 1918, the Declaration to the Seven was issued. It stated that British policy was to let the people of the Ottoman Empire's occupied regions decide their own future government.

Allenby's Promise to Faisal

On October 19, 1918, General Allenby told the UK Government that he had promised Faisal that any military actions were temporary. He said they would not affect the final peace agreement, where Arabs would have a representative. Allenby also told Faisal that the Allies were honor-bound to reach a settlement based on the wishes of the people involved.

The Anglo-French Declaration of 1918

In this declaration on November 7, 1918, Britain and France stated their goal was to free the people oppressed by the Turks. They wanted to establish national governments chosen by the local people. This declaration was seen by historians as misleading.

After the War: 1919 to 1925

The Sherifian Plan

Just before the war with the Ottomans ended, the British Foreign Office discussed T.E. Lawrence's "Sherifian Plan." This plan suggested Hussein's sons become leaders in Syria and Mesopotamia. One reason for this was to fulfill a promise to the Hashemites from the McMahon correspondence.

Mandates

The Paris Peace Conference in 1919 was held to decide how to divide territories after the war. Prince Faisal, representing King Hussein, asked for an Arab state under British control.

In January 1920, Prince Faisal signed an agreement with French Prime Minister Georges Clemenceau. This agreement recognized "the right of the Syrians to unite to govern themselves as an independent nation." On March 8, 1920, a meeting in Damascus declared an independent state of Syria. This new state included parts of Syria, Palestine, and northern Mesopotamia. Faisal was declared king. In April 1920, the San Remo conference quickly met in response. There, the Allies gave control of Palestine and Mesopotamia to Britain, and Syria and Lebanon to France.

Britain and France agreed to recognize the temporary independence of Syria and Mesopotamia. But Palestinian independence was not mentioned. France decided to rule Syria directly. They took military action in June 1920, removing King Faisal from Damascus. In Palestine, the UK appointed a High Commissioner and set up their own rule. The January 1919 Faisal–Weizmann Agreement was a short-lived agreement for Arab–Jewish cooperation in Palestine. Faisal had mistakenly thought this would be part of the Arab kingdom. Faisal treated Palestine differently in his presentation to the Peace Conference. He said Palestine, because of its special nature, should be considered by all parties.

The agreement was never put into action. At the same conference, US Secretary of State Robert Lansing asked if the Jewish national home meant an independent Jewish government. The head of the Zionist group said no. Lansing believed the system of mandates was a way for the Great Powers to hide their division of war spoils.

Hussein's Downfall

In 1919, King Hussein refused to sign the Treaty of Versailles. After February 1920, the British stopped paying him. In August 1920, the British asked Hussein to sign the Treaty of Sèvres, which recognized his kingdom, and offered him money. Hussein refused. In 1921, he said he couldn't sign a document that gave Palestine to Zionists and Syria to foreigners.

After the 1921 Cairo Conference, T. E. Lawrence was sent to get Hussein's signature on a treaty for a yearly payment. This also failed. In 1923, the British tried again to settle issues with Hussein, but it failed. Hussein kept refusing to recognize any of the mandates he felt were his. In March 1924, the UK government stopped talks. Within six months, they withdrew support for Hussein. They supported Ibn Saud, who then took over Hussein's kingdom.

Disagreements Over Land and Palestine

McMahon's letter to Hussein on October 24, 1915, said Britain would recognize Arab independence with some exceptions. The original letters were in English and Arabic. There are slightly different English translations.

The letter stated: "The districts of Mersina and Alexandretta, and portions of Syria lying to the west of the districts of Damascus, Homs, Hama and Aleppo, cannot be said to be purely Arab, and must on that account be excepted from the proposed limits and boundaries.

With the above modification and without prejudice to our existing treaties concluded with Arab Chiefs, we accept these limits and boundaries, and in regard to the territories therein in which Great Britain is free to act without detriment to interests of her ally France, I am empowered in the name of the Government of Great Britain to give the following assurance and make the following reply to your letter:

Subject to the above modifications, Great Britain is prepared to recognize and support the independence of the Arabs within the territories in the limits and boundaries proposed by the Sherif of Mecca."

The letters were written first in English, then translated to Arabic, or vice versa. The exact writer and translator are not clear.

The "Portions of Syria" Debate

The argument about Palestine started because Palestine is not directly named in the McMahon–Hussein Correspondence. However, it was within the boundaries Hussein first suggested. McMahon accepted Hussein's boundaries "subject to modification." He suggested that "portions of Syria lying to the west of the districts of Damascus, Homs, Hama and Aleppo cannot be said to be purely Arab and should be excluded." Until 1920, British government papers suggested Palestine was meant to be part of the Arab area. Their interpretation changed in 1920, leading to public disagreement. Each side used small details of the wording to support their views.

Historian Jonathan Schneer used an example to explain the main disagreement: Imagine a line from the districts of New York, New Haven, New London, and Boston. It excludes land west of an imaginary coastal kingdom. If "districts" means "nearby areas," that's one thing. But if it means "provinces" or "states," it's completely different. There are no states of Boston, New London, or New Haven, just as there were no provinces of Hama and Homs. But there is a state of New York, just as there was a vilayet (province) of Damascus. Land west of New York State is different from land west of the district of New York City. The same applies to Damascus.

More than 50 years later, historian Arnold J. Toynbee shared his thoughts on the debate. He said if McMahon's "districts" meant provinces, it would mean McMahon was either very uninformed about Ottoman geography or was being tricky. Toynbee found both ideas hard to believe.

The "Without Harm to France" Debate

In the letter of October 24, the English version says: "...we accept those limits and boundaries; and in regard to those portions of the territories therein in which Great Britain is free to act without detriment to the interests of her ally France." At a meeting in December 1920, the English and Arabic texts were compared. An official present said that in the Arabic version sent to King Hussein, it seemed Britain was free to act without harming France in the entire area. This was a problem for the British, as they had used this phrase to tell the French they had protected their rights, and to tell the Arabs that they would need to deal with the French later.

James Barr wrote that McMahon wanted to protect French interests. But the translator lost this meaning in the Arabic version. In a British Cabinet analysis from May 1917, William Ormsby-Gore, a Member of Parliament, wrote that French plans in Syria seemed to go against the Allies' war goals. He questioned if British promises to King Hussein were consistent with French plans to make Syria and Upper Mesopotamia like another Tunis. He felt it was time to tell the French about their promises to Hussein.

Declassified British papers show a message from McMahon to the Foreign Secretary, Lord Grey, on October 18, 1915. McMahon described talks with a Syrian nationalist who said Arabs would fight if the French took Damascus, Homs, Hama, and Aleppo. But he thought they would accept some changes to the northern boundaries. Based on this, McMahon suggested the wording: "In so far as Britain was free to act without detriment to the interests of her present Allies, Great Britain accepts the principle of the independence of Arabia within limits propounded by the Sherif of Mecca." Lord Grey allowed McMahon to make this promise, with the exception for the Allies.

The Arab View

The Arabs argued that Palestine could not be excluded because it was far south of the named places. They said the vilayet (province) of Damascus did not exist. The district (sanjak) of Damascus only covered the area around the city. Palestine was part of the vilayet of Syria A-Sham, which was not mentioned in the letters. Supporters of this view also noted that during the war, thousands of messages were dropped in Palestine. These messages, from the Sharif Hussein and the British, said that an Anglo-Arab agreement had been made to secure Arab independence.

The British View

In November 1918, British historian Arnold J. Toynbee prepared a memo for the Political Intelligence Department. This memo was used for the Peace Conference. Later, Jan Smuts asked for a summary, and Toynbee produced another document. These documents were discussed by the Eastern Committee of the Cabinet in December 1918. T. E. Lawrence also attended.

The Eastern Committee met nine times to create policies for the negotiators. Henry Erle Richards summarized Toynbee's work into a "P-memo" for the Peace Conference delegates.

In public, Arthur Balfour was criticized when some politicians said secret treaties should be changed. They felt these treaties went against why Britain entered the war. In response to growing criticism about the conflicting promises, the 1922 Churchill White Paper stated that Palestine had always been excluded from the Arab area. Although this went against many earlier government documents, those documents were not known to the public. For this White Paper, a British official named John Evelyn Shuckburgh talked with McMahon. They relied on a 1920 memo by Major Hubert Young. Young noted that in the original Arabic text, the word translated as "districts" was "vilayets" (provinces). He concluded that "district of Damascus" meant the province of Damascus, which extended south but excluded most of Palestine.

| British Interpretations: 1916–39 | ||

|---|---|---|

| Source | Context | Quotation |

| Henry McMahon 26 October 1915 |

Message to British Foreign Secretary Edward Grey | "I have been definite in stating that Great Britain will recognise the principle of Arab independence in purely Arab territory... but have been equally definite in excluding Mersina, Alexandretta and those districts on the northern coasts of Syria, which cannot be said to be purely Arab, and where I understand that French interests have been recognised. I am not aware of the extent of French claims in Syria, nor of how far His Majesty's Government have agreed to recognise them. Hence, while recognising the towns of Damascus, Hama, Homs and Aleppo as being within the circle of Arab countries, I have endeavoured to provide for possible French pretensions to those places by a general modification to the effect that His Majesty's Government can only give assurances in regard to those territories "in which she can act without detriment to the interests of her ally France."" |

| Arab Bureau for Henry McMahon 19 April 1916 |

Memorandum sent by Henry McMahon to the Foreign Office | Interpreted Palestine as being included in the Arab area:"What has been agreed to, therefore, on behalf of Great Britain is: (1) to recognise the independence of those portions of the Arab-speaking areas in which we are free to act without detriment to the interests of France. Subject to these undefined reservations the said area is understood to be bounded N. by about lat. 37, east by the Persian frontier, south by the Persian Gulf and Indian Ocean, west by the Red Sea and the Mediterranean up to about lat. 33, and beyond by an indefinite line drawn inland west of Damascus, Homs, Hama and Aleppo: all that lies between this last line and the Mediterranean being, in any case, reserved absolutely for future arrangement with the French and the Arabs." |

| War Office 1 July 1916 |

The Sherif of Mecca and the Arab Movement | Adopted the same conclusions as the Arab Bureau memorandum of April 1916 |

| Arnold J. Toynbee, Foreign Office Political Intelligence Department November 1918 |

War Cabinet Memorandum on British Commitments to King Husein |

"With regard to Palestine, His Majesty's Government are committed by Sir H. McMahon's letter to the Sherif on the 24th October, 1915, to its inclusion in the boundaries of Arab independence. But they have stated their policy regarding the Palestinian Holy Places and Zionist colonisation in their message to him of the 4th January, 1918."

|

| Lord Curzon 5 Dec 1918 |

Chairing the Eastern Committee of the British War Cabinet | "First, as regards the facts of the case. The various pledges are given in the Foreign Office paper [E.C. 2201] which has been circulated, and I need only refer to them in the briefest possible words. In their bearing on Syria they are the following: First there was the letter to King Hussein from Sir Henry McMahon of the 24th October 1915, in which we gave him the assurance that the Hedjaz, the red area which we commonly call Mesopotamia, the brown area or Palestine, the Acre-Haifa enclave, the big Arab areas (A) and (B), and the whole of the Arabian peninsula down to Aden should be Arab and independent." "The Palestine position is this. If we deal with our commitments, there is first the general pledge to Hussein in October 1915, under which Palestine was included in the areas as to which Great Britain pledged itself that they should be Arab and independent in the future... the United Kingdom and France—Italy subsequently agreeing—committed themselves to an international administration of Palestine in consultation with Russia, who was an ally at that time... A new feature was brought into the case in November 1917, when Mr Balfour, with the authority of the War Cabinet, issued his famous declaration to the Zionists that Palestine 'should be the national home of the Jewish people, but that nothing should be done—and this, of course, was a most important proviso—to prejudice the civil and religious rights of the existing non-Jewish communities in Palestine. Those, as far as I know, are the only actual engagements into which we entered with regard to Palestine." |

| H. Erle Richards January 1919 |

Peace Conference: Memorandum Respecting Palestine, for the Eastern Committee of the British War Cabinet, ahead of the Paris Peace Conference | "A general pledge was given to Husein in October, 1915, that Great Britain was prepared (with certain exceptions) to recognise and support the independence of the Arabs with the territories included in the limits and boundaries proposed by the Sherif of Mecca; and Palestine was within those territories. This pledge was restricted to those portions of the territories in which Great Britain was free to act without detriment to the interests of her Ally, France." |

| Arthur Balfour 19 August 1919 |

Memorandum by Mr. Balfour respecting Syria, Palestine, and Mesopotamia | "In 1915 we promised the Arabs independence; and the promise was unqualified, except in respect of certain territorial reservations... In 1915 it was the Sherif of Mecca to whom the task of delimitation was to have been confided, nor were any restrictions placed upon his discretion in this matter, except certain reservations intended to protect French interests in Western Syria and Cilicia." |

| Hubert Young, of the British Foreign Office 29 November 1920 |

Memorandum on Palestine Negotiations with the Hedjaz, written prior to the arrival of Faisal bin Hussein in London on 1 December 1920. | Interpreted the Arabic translation to be referring to the Vilayet of Damascus. This was the first time an argument was put forward that the correspondence was intended to exclude Palestine from the Arab area.: "With regard to Palestine, a literal interpretation of Sir H. McMahon's undertaking would exclude from the areas in which His Majesty's Government were prepared to recognize the 'independence of the Arabs' only that portion of the Palestine mandatory area [which included 'Transjordan '] which lies to the west of the 'district of Damascus'. The western boundary of the 'district of Damascus' before the war was a line bisecting the lakes of Huleh and Tiberias; following the course of the Jordan; bisecting the Dead Sea; and following the Wadi Araba to the Gulf of Akaba.'" |

| Eric Forbes Adam October 1921 |

Letter to John Evelyn Shuckburgh | "On the wording of the letter alone, I think either interpretation is possible, but I personally think the context of that particular McMahon letter shows that McMahon (a) was not thinking in terms of vilayet boundaries etc., and (b) meant, as Hogarth says, merely to refer to the Syrian area where French interests were likely to be predominant and this did not come south of the Lebanon. ... Toynbee, who went into the papers, was quite sure his interpretation of the letter was right and I think his view was more or less accepted until Young wrote his memorandum." |

| David George Hogarth 1921 |

A talk delivered in 1921 | "...that Palestine was part of the area in respect to which we undertook to recognise the independence of the Arabs" |

| T. E. Lawrence (Lawrence of Arabia) February 1922 |

Autobiography: Seven Pillars of Wisdom | "The Arab Revolt had begun on false pretences. To gain the Sherif's help our Cabinet had offered, through Sir Henry McMahon, to support the establishment of native governments in parts of Syria and Mesopotamia, 'saving the interests of our ally, France'. The last modest clause concealed a treaty (kept secret, till too late, from McMahon, and therefore from the Sherif) by which France, England and Russia agreed to annex some of these promised areas, and to establish their respective spheres of influence over all the rest... Rumours of the fraud reached Arab ears, from Turkey. In the East persons were more trusted than institutions. So the Arabs, having tested my friendliness and sincerity under fire, asked me, as a free agent, to endorse the promises of the British Government. I had had no previous or inner knowledge of the McMahon pledges and the Sykes-Picot treaty, which were both framed by war-time branches of the Foreign Office. But, not being a perfect fool, I could see that if we won the war the promises to the Arabs were dead paper. Had I been an honourable adviser I would have sent my men home, and not let them risk their lives for such stuff. Yet the Arab inspiration was our main tool in winning the Eastern war. So I assured them that England kept her word in letter and spirit. In this comfort they performed their fine things: but, of course, instead of being proud of what we did together, I was continually and bitterly ashamed." |

| Henry McMahon 12 March 1922 and 22 July 1937 |

Letter to John Evelyn Shuckburgh, in preparation for the Churchill White Paper Letter to The Times |

"It was my intention to exclude Palestine from independent Arabia, and I hoped that I had so worded the letter as to make this sufficiently clear for all practical purposes. My reasons for restricting myself to specific mention of Damascus, Hama, Homs and Aleppo in that connection in my letter were: 1) that these were places to which the Arabs attached vital importance and 2) that there was no place I could think of at the time of sufficient importance for purposes of definition further South of the above. It was as fully my intention to exclude Palestine as it was to exclude the more Northern coastal tracts of Syria."

|

| Winston Churchill 3 June 1922 |

Churchill White Paper following the 1921 Jaffa riots |

"In the first place, it is not the case, as has been represented by the Arab Delegation, that during the war His Majesty's Government gave an undertaking that an independent national government should be at once established in Palestine. This representation mainly rests upon a letter dated 24 October 1915, from Sir Henry McMahon, then His Majesty's High Commissioner in Egypt, to the Sharif of Mecca, now King Hussein of the Kingdom of the Hejaz. That letter is quoted as conveying the promise to the Sherif of Mecca to recognise and support the independence of the Arabs within the territories proposed by him. But this promise was given subject to a reservation made in the same letter, which excluded from its scope, among other territories, the portions of Syria lying to the west of the District of Damascus. This reservation has always been regarded by His Majesty's Government as covering the vilayet of Beirut and the independent Sanjak of Jerusalem. The whole of Palestine west of the Jordan was thus excluded from Sir. Henry McMahon's pledge."

|

| Duke of Devonshire's Colonial Office 17 February 1923 |

British Cabinet Memorandum regarding Policy in Palestine | "The question is: Did the excluded area cover Palestine or not? The late Government maintained that it did and that the intention to exclude Palestine was clearly under stood, both by His Majesty's Government and by the Sherif, at the time that the correspondence took place. Their view is supported by the fact that in the following year (1916) we concluded an agreement with the French and Russian Governments under which Palestine was to receive special treatment-on an international basis. The weak point in the argument is that, on the strict wording of Sir H. McMahon's letter, the natural meaning of the phrase "west of the district of Damascus" has to be somewhat strained in order to cover an area lying considerably to the south, as well as to the west, of the City of Damascus." |

| Duke of Devonshire 27 March 1923 |

Diary of 9th Duke of Devonshire, Chatsworth MSS | "Expect we shall have to publish papers about pledges to Arabs. They are quite inconsistent, but luckily they were given by our predecessors." |

| Edward Grey 27 March 1923 |

Debate in the House of Lords; Viscount Grey had been Foreign Secretary in 1915 when the letters were written | "I do not propose to go into the question whether the engagements are inconsistent with one another, but I think it is exceedingly probable that there are inconsistencies... I seriously suggest to the Government that the best way of clearing our honour in this matter is officially to publish the whole of the engagements relating to the matter, which we entered into during the war... It would be very desirable, from the point of view of honour, that all these various pledges should be set out side by side, and then, I think, the most honourable thing would be to look at them fairly, see what inconsistencies there are between them, and, having regard to the nature of each pledge and the date at which it was given, with all the facts before us, consider what is the fair thing to be done." |

| Lord Islington 27 March 1923 |

Debate in the House of Lords | "the claim was made by the British Government to exclude from the pledge of independence the northern portions of Syria... It was described as being that territory which lay to the west of a line from the city of Damascus... up to Mersina... and, therefore, all the rest of the Arab territory would come under the undertaking... Last year Mr. Churchill, with considerable ingenuousness, of which, when in a difficult situation, he is an undoubted master, produced an entirely new description of that line." |

| Lord Buckmaster 27 March 1923 |

Debate in the House of Lords; Buckmaster had been Lord Chancellor in 1915 when the letters were written and voted against the 1922 White Paper in the House of Lords. | "these documents show that, after an elaborate correspondence in which King Hussein particularly asked to have his position made plain and definite so that there should be no possibility of any lurking doubt as to where he stood as from that moment, he was assured that within a line that ran north from Damascus through named places, a line that ran almost due north from the south and away to the west, should be the area that should be he excluded from their independence, and that the rest should be theirs." |

| Gilbert Clayton 12 April 1923 |

An unofficial note given to Herbert Samuel, described by Samuel in 1937, eight years after Clayton's death | "I can bear out the statement that it was never the intention that Palestine should be included in the general pledge given to the Sharif; the introductory words of Sir Henry’s letter were thought at that time—perhaps erroneously—clearly to cover that point." |

| Gilbert Clayton 11 March 1919 |

Memorandum, 11 March 1919. Lloyd George papers F/205/3/9. House of Lords. | "We are committed to three distinct policies in Syria and Palestine:–

A. We are bound by the principles of the Anglo-French Agreement of 1916 [Sykes-Picot], wherein we renounced any claim to predominant influence in Syria. B. Our agreements with King Hussein... have pledged us to support the establishment of an Arab state, or confederation of states, from which we cannot exclude the purely Arab portions of Syria and Palestine. C. We have definitely given our support to the principle of a Jewish home in Palestine and, although the initial outlines of the Zionist programme have been greatly exceeded by the proposals now laid before the Peace Congress, we are still committed to a large measure of support to Zionism. The experience of the last few months has made it clear that these three policies are incompatible ... " |

| Lord Passfield, Secretary of State for the Colonies 25 July 1930 |

Memorandum to Cabinet: "Palestine: McMahon Correspondence" | "The question whether Palestine was included within the boundaries of the proposed Arab State is in itself extremely complicated. From an examination of Mr. Childs’s able arguments, I have formed the judgement that there is a fair case for saying that Sir H. McMahon did not commit His Majesty’s Government in this sense. But I also have come to the conclusion that there is much to be said on both sides and that the matter is one for the eventual judgement of the historian, and not one in which a simple, plain and convincing statement can be made." |

| Drummond Shiels, Under-Secretary of State for the Colonies 1 August 1930 |

House of Commons debate | His Majesty's Government have been impressed by the feeling shown in the House of Commons on various occasions, and especially in the debate on the Adjournment on the 7th May, with regard to the correspondence which took place in 1915–16 between Sir Henry McMahon and the Sherif Husein of Mecca. They have, therefore, thought it necessary to re-examine this correspondence fully in the light of the history of the period and the interpretations which have been put upon it. There are still valid reasons, entirely unconnected with the question of Palestine, which render it in the highest degree undesirable in the public interest to publish the correspondence. These reasons may be expected to retain their force for many years to come. There are not sufficient grounds for holding that by this correspondence His Majesty's Government intended to pledge themselves, or did, in fact, pledge themselves, to the inclusion of Palestine in the projected Arab State. Sir H. McMahon has himself denied that this was his intention. The ambiguous and inconclusive nature of the correspondence may well, however, have left an impression among those who were aware of the correspondence that His Majesty's Government had such an intention. |

| W. J. Childs, of the British Foreign Office 24 October 1930 |

Memorandum on the Exclusion of Palestine from the Area assigned for Arab Independence by McMahon–Hussein Correspondence of 1915–16 | Interpreted Palestine as being excluded from the Arab area: "...the interests of France so reserved in Palestine must be taken as represented by the origins French claim to possession of the whole of Palestine. And, therefore, that the general reservation of French interests is sufficient by itself to exclude Palestine from the Arab area." |

| Reginald Coupland, commissioner on the Palestine Royal Commission 5 May 1937 |

Explanation to the Foreign Office regarding the commission's abstention | "a reason why the Commission did not intend to pronounce upon Sir H. McMahon’s pledge was that in everything else their report was unanimous, but that upon this point they would be unlikely to prove unanimous." |

| George William Rendel, Head of the Eastern Department of the Foreign Office 26 July 1937 |

Minute commenting on McMahon's 23 July 1937 letter | "My own impression from reading the correspondence has always been that it is stretching the interpretation of our caveat almost to breaking point to say that we definitely did not include Palestine, and the short answer is that if we did not want to include Palestine, we might have said so in terms, instead of referring vaguely to areas west of Damascus, and to extremely shadowy arrangements with the French, which in any case ceased to be operative shortly afterwards... It would be far better to recognise and admit that H.M.G. made a mistake and gave flatly contradictory promises – which is of course the fact." |

| Lord Halifax, Foreign Secretary January 1939 |

Memorandum on Palestine: Legal Arguments Likely to be Advanced by Arab Representatives |

"...it is important to emphasise the weak points in His Majesty's Governments case, e.g. :–

|

| Committee Set up to Consider Certain Correspondence 16 March 1939 |

Committee set up in preparation for the White Paper of 1939 | "It is beyond the scope of the Committee to express an opinion upon the proper interpretation of the various statements mentioned in paragraph 19 and such an opinion could not in any case be properly expressed unless consideration had also been given to a number of other statements made during and after the war. In the opinion of the Committee it is, however, evident from these statements that His Majesty's Government were not free to dispose of Palestine without regard for the wishes and interests of the inhabitants of Palestine, and that these statements must all be taken into account in any attempt to estimate the responsibilities which—upon any interpretation of the Correspondence—His Majesty's Government have incurred towards those inhabitants as a result of the Correspondence." |

While some British governments said they didn't intend to promise Palestine to Hussein, they sometimes admitted the problems in the legal wording. A committee set up by the British in 1939 to clarify the arguments said many promises had been made. They said all of them needed to be studied together. Arab representatives told the committee that whatever McMahon intended didn't matter legally. What mattered were his actual statements, which were promises from the British government. They also noted that McMahon was acting for the Foreign Secretary, Lord Grey. Lord Grey himself said in 1923 that he had serious doubts about the Churchill White Paper's interpretation of the promises he had made to Sharif Hussein.

See also

| Valerie Thomas |

| Frederick McKinley Jones |

| George Edward Alcorn Jr. |

| Thomas Mensah |