Motul de San José facts for kids

A badly fire-damaged stela in Group C

|

|

| Location | San José |

|---|---|

| Region | Petén Department, |

| Coordinates | 17°1′35″N 89°54′5″W / 17.02639°N 89.90139°W |

| History | |

| Periods | Middle Preclassic to Early Postclassic |

| Cultures | Maya |

| Site notes | |

| Excavation dates | 1998–2008 |

| Archaeologists | Antonia Foias, Kitty Emery Proyecto Arqueológico Motul de San José |

| Architecture | |

| Architectural styles | Classic Maya |

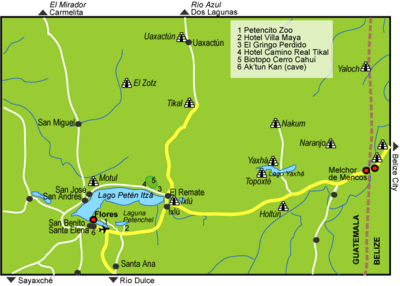

Motul de San José is an ancient Maya city. It was known long ago as Ik'a (meaning 'Windy Water'). This city is located north of Lake Petén Itzá in the Petén Basin area of southern Guatemala. It's only a few kilometers from the modern village of San José.

Motul de San José was a medium-sized center for important public and religious events. It was a key political and economic hub during the Late Classic period (around AD 650–950). People first settled here between 600 and 300 BC. This was during the Middle Preclassic period. The city grew and was continuously lived in until the Early Postclassic period, around AD 1250. It was most active during the Late Preclassic and Late Classic times.

Motul de San José had changing alliances with other powerful Maya cities. In the late 300s AD, it was linked to Tikal. By the 600s, it switched its loyalty to Calakmul, Tikal's big rival. Then, in the early 700s, it went back to Tikal. In the late 700s, it seems Dos Pilas conquered Motul de San José.

The city had easy access to many natural resources. A nearby port called La Trinidad de Nosotros was important for trade. Exotic goods came in, and local items like chert (a type of rock) and pottery were sent out. The local area had different types of soil for farming. The port also provided fresh water foods like turtles, crocodiles, and freshwater molluscs. Deer were hunted for protein, especially for the upper class. Freshwater snails were a main protein source for common people.

Motul de San José is famous for its "Ik-style" painted pottery. These pots show scenes of Maya nobles doing courtly activities. The Ik-style pottery often had pink or pale red hieroglyphs. It also showed dancers wearing masks and very realistic pictures of people. Motul de San José was the capital of a kingdom that included several smaller towns. One of these was a port on Lake Petén Itzá.

Where is Motul de San José?

Motul de San José is about 3 kilometers (1.9 miles) north of Lake Petén Itzá. It is in the middle of the Petén department in Guatemala. The closest large town is Flores, about 10.5 kilometers (6.5 miles) south across the lake. The villages of San José and San Andrés are also nearby, both to the south.

The ancient city sits on a limestone plateau. This area has ridges and lower areas with clay soils. Water from these low areas flows into Lake Petén Itzá or the Akte River. The Kantetul River, which is seasonal, flows near the site. It eventually connects to the San Pedro River, which leads to Mexico and the Gulf of Mexico. Access to water was very important for Maya cities. They used canoes for trade on rivers and the sea.

Motul de San José is surrounded by many smaller sites. It is about 32 kilometers (20 miles) southwest of the famous ruins of Tikal. The site is on a hill about 180 meters (590 feet) above sea level.

Today, Motul de San José is part of the Motul Ecological Park. This park is managed by the Guatemalan Institute of Anthropology and History (IDAEH) and local communities. The park covers about 2.2 square kilometers (0.85 square miles).

What is an Emblem Glyph?

Ancient Maya cities and kingdoms had special symbols called emblem glyphs. These were like royal titles in hieroglyphic texts. They usually had three parts: "divine," "lord," and the name of the kingdom. Understanding these symbols helped experts learn about Maya politics.

The emblem glyph for Motul de San José includes the sign ik, meaning "breath" or "wind." This symbol is found on monuments and pottery from the 700s and 800s. A pot with this symbol, showing king Lamaw Ek', was found far away at Altar de Sacrificios. This shows that Motul de San José traded or interacted with distant places.

Economy and Daily Life

Most basic natural resources were easy to find near Motul de San José. The local soils were good for growing corn and other crops. La Trinidad de Nosotros, a site on Lake Petén Itzá, was an important port. It helped Motul de San José import and export goods. Other foods not found nearby were likely supplied by smaller towns around the city. La Trinidad also provided fresh water foods like crocodiles, fish, and turtles.

Chert rock was available from hills north of the lake. A workshop for making chert tools was found in Motul de San José. Ceramic figures were made in the royal palace area and other noble homes.

A small site called Chak Maman Tok', a few kilometers southwest, was a major center for making chert tools. Even though it was small, it was very important to Motul de San José's economy.

Different styles of noble homes suggest that the upper class in Motul de San José had different groups. These included the royal family, royal courtiers, and lower-ranking nobles.

The Kantetul River, though seasonal now, was once a navigable waterway. It might have been an important link to the San Pedro River. This river was a major trade route in ancient times.

Ik Style Ceramics

Motul de San José is likely where the famous "Ik-style" painted pottery came from. This idea has been supported by recent archaeological digs. These beautiful pots and cylindrical vessels were first linked to an unknown site called Ik in the 1970s. This was because of the emblem glyphs on them. Investigations from 1998 to 2004 confirmed that Motul de San José was indeed Ik. Chemical tests show these pots were made in workshops in Motul and nearby towns.

Ik-style pottery has special features. These include hieroglyphs painted in pink or pale red. They also show scenes with dancers wearing masks. One unique feature is the realistic way subjects are shown, which is rare in Mesoamerican art. Over 30 complete pots of this style exist, many from unknown locations. They have been compared to pottery pieces found at Motul de San José. The pots show scenes of courtly life from the Petén region in the 700s AD. These include diplomatic meetings, feasts, bloodletting rituals, warriors, and the sacrifice of war prisoners.

The different art styles and chemical makeup of Ik-style pottery suggest they were made in several workshops around Motul de San José. They are divided into five types, four from Motul itself and one from a nearby town. Lower-quality examples were likely made in less important sites within the Motul de San José kingdom. These pots were probably made between 740 and 800 AD. They were given as gifts to seal alliances between Maya kingdoms.

Interestingly, chemical tests show that the same workshops made both the highest-quality Ik-style pots and everyday household pottery. High-quality Ik-style ceramics from Motul de San José have been found across the Maya region. This includes Tikal and Uaxactún to the northeast, Copán far to the south, and Altar de Sacrificios, Tamarindito, and Seibal in western Petén.

A rare feature on Motul de San José pottery is the "X-ray style." This shows a figure wearing a mask but also reveals their face underneath. This style is also seen on sculptures at sites that Motul de San José had contact with, like Dos Pilas, Machaquila, Tikal, and Yaxchilan. This X-ray style is on at least nine painted pots from Motul de San José and on Stela 2.

How People Lived and What They Ate

Motul de San José was lived in from the Middle Preclassic to the Early Postclassic periods. However, it was most populated during the Late Classic period. The city's main area had about 250 buildings per square kilometer. The suburbs had 125 buildings per square kilometer, and the outer areas had 79.

The area around Motul de San José, where resources were gathered, likely stretched 5 to 7 kilometers (3 to 4.3 miles). This area included smaller towns like Kantetul and La Trinidad de Nosotros. It also had two main water sources: Lake Petén Itzá and the Kantetul River. The land around the city had various soils good for farming. About 20% was very fertile. Over 50% was fertile but needed care like fertilization or crop rotation. Only 14% was low-fertility clay soil, mostly for corn or left unfarmed. Studies show corn was grown near homes as well as in outer areas.

Archaeological digs show that people in Motul de San José ate many different animals. These included dogs, turtles (like pond sliders and Mesoamerican river turtles), freshwater snails, white-tailed deer, red brocket (a small deer), white-lipped peccary, rabbits, lowland pacas, Central American agouti, and nine-banded armadillos. Only dogs were domesticated by the Maya. Most protein came from hunting and fishing. The most common food animals were white-tailed deer, river clams, and river turtles.

Some animal remains, like those of jaguars, ocelots, and crocodiles, were found with elite people. These animals were likely used for rituals or trade, not just food. Freshwater snails were more common in the diet of lower-class families. Deer remains were found more with the city's elite residents.

At La Trinidad de Nosotros, most animal remains were from water species. At Motul de San José, most were from land species. Aquatic animal products brought to Motul de San José were more often eaten by the elite than by commoners.

History of Motul de San José

Early Times (Preclassic Period)

Motul de San José was first settled between 600 and 300 BC. It was probably a small place then. Some of its nearby towns, like La Trinidad de Nosotros, were also settled around this time.

The city grew a lot during the Late Preclassic period (300 BC–AD 300). It became a large center. Many major buildings were constructed. La Trinidad de Nosotros also grew and became more important than Motul de San José during this time.

Classic Period

Motul de San José had shifting alliances. In the late 300s AD, it was under Tikal's influence. By the 600s, texts say it was controlled by Calakmul, Tikal's main enemy. Then, in the early 700s, it returned to Tikal's side.

Early Classic Period

Not many Early Classic pottery pieces have been found at Motul de San José itself. This suggests the city might have been mostly empty during this time. However, some Early Classic pottery was found in nearby Trinidad de Nosotros.

Late Classic Period

Motul de San José had its second major growth spurt during the Late Classic period (AD 600–830). Most of the city's large buildings were constructed then. The city reached its biggest size. Motul de San José became one of the three most important cities around Lake Petén Itzá. It was about the same size as Tayasal. Its smaller towns also grew.

In the 700s AD, the city had important connections with Maya cities to the southwest. This included cities in the Petexbatún region and along the Pasión and Usumacinta rivers. It's thought that the spread of Ik-style pottery in elite tombs in the Petexbatún region might be linked to Motul de San José's military defeat by Dos Pilas. These high-quality pots might have been part of a tribute payment. After this defeat, Motul de San José stopped putting up carved stone monuments (stelae). But its history continued to be recorded on Ik-style pottery.

Politics in the Late Classic

During the Late Classic period, Motul de San José was located between two powerful enemies: Tikal to the north and the Petexbatún kingdom to the southwest. The Petexbatún kingdom was a vassal (a state controlled by another) of Calakmul, Tikal's enemy. Cities like Motul de San José, located on borders, often became centers of political activity. They tried to use the changing power of their neighbors to their own benefit. Motul de San José's rich pottery tradition shows the many politically motivated feasts held in the city.

In the 600s AD, hieroglyphic texts say Motul de San José was a vassal of Calakmul. By the early 700s, it switched its loyalty to Jasaw Chan K'awiil I, the king of Tikal. Then, in the mid-700s, it fell under the power of Petexbatún, which was a vassal of Calakmul. Later, it switched back to Tikal. Despite these changing alliances, Motul de San José was quite independent and a powerful kingdom in the 700s AD. Its ruler used the kaloomte title, given to high kings. The city's rulers were very successful in Maya politics. They used feasts, wars, trade, and political marriages to gain power.

Records show that before 731, a lord of Motul was captured by a lord of Machaquilá. In 740, Machaquila attacked Motul de San José. In 745, a text from Dos Pilas says a lord of Motul was captured by K'awiil Chan K'inich of Dos Pilas. In the mid-700s AD, Motul de San José was closely allied with Yaxchilan. This is shown by the fact that Yaxchilan's king, Yaxun B'alam IV, married two women from Motul de San José.

Known Rulers

Here are some known rulers of Motul de San José:

| Name | Ruled |

|---|---|

| Sak Muwaan | sometime between 700–726 |

| Tayel Nichan K'inich Nich'ich | c.725–740? |

| Yajaw Te' K'inich | 29 September 740?–755? |

| Lamaw Ek' | 755?–779 |

| Sak Ch’een | ?–? Late Classic. |

| Kan Ek' | c.849 |

An Ik-style pot says it belonged to Chuy-ti Chan, the son of Sak Muwaan. Sak Muwaan was the divine lord of Motul de San José from AD 700 to 726. Chuy-ti Chan was an artist and ballplayer.

Two rulers, Yajawte' K'inich and Lamaw Ek', are often shown on Ik-style pottery. Lamaw Ek' seems to have ruled after Yajawte' K'inich. Yajawte' K'inich is shown dancing on one pot and on Stelae 2 and 6. One pot suggests Yajawte' K'inich might have died in AD 755. Another pot records Lamaw Ek's death in AD 779.

Terminal Classic Period

Motul de San José's population dropped a lot at the end of the Classic Period (AD 830–1000). Building also slowed down. Pottery from this time is common but mostly found in Motul de San José and its main satellite, La Trinidad de Nosotros. Even though it declined, building didn't stop completely.

An inscription from AD 830 mentions the last known ruler of Machaquilá. This might show a long connection between the two cities. A stone monument (Stela 10) from Seibal, dated around 849 AD, names Kan Ek' as ruler of Motul de San José. It lists Motul de San José as one of four main kingdoms in the mid-800s, along with Calakmul, Tikal, and Seibal.

Itza Migration

Some believe that the Itza Maya people from Motul de San José began moving north to the Yucatán Peninsula at the end of the Classic Period. Old stone monuments at the site mention the "King of the Itzá." This shows the Itza were already in the Petén region at that time. The nearby village of San José is one of the last Itzá communities in Petén today.

Later Times (Postclassic Period)

Not much is known about how much activity happened in the Motul de San José area during the Postclassic Period. There was some activity during the Early Postclassic (AD 1000–1250). Small-scale building and pottery from this time have been found. La Trinidad de Nosotros was a small village then and has some of the best examples of Early Postclassic pottery.

There is little sign of people living in the Motul de San José area during the Late Postclassic (AD 1250–1697). It's possible that La Trinidad de Nosotros was Xililchi, a settlement visited by the Spanish explorer Martín de Ursúa after the fall of the Itza capital Noj Petén in 1697. But archaeologists haven't found definite proof yet.

Modern History

In early 1695, a Spanish friar named Andrés de Avendaño might have called the satellite site of Akte Tanxulukmul. Teoberto Maler visited Motul de San José in May 1895. He wrote about one of the stone monuments (stelae) in his report.

Before the Motul Ecological Park was created, the site was used for farming corn. The site has been damaged several times by wildfires. These fires were caused by uncontrolled burning of fields in 1986, 1987, and 1998. The last fire badly damaged the stelae in the city center.

In 1998, the road to Motul de San José was improved, making it easier for tourists to visit.

The Motul de San José Archaeological Project studied the site and its surrounding towns from 1998 to 2008. This project was led by Antonia Foias and Kitty Emery.

What Motul de San José Looks Like

About 230 buildings have been mapped in a 2 square kilometer (0.77 square mile) area. However, the city was probably much larger. Its total size is thought to be about 4.18 square kilometers (1.6 square miles), but only about a third has been mapped. The city's ceremonial center covers 0.4 square kilometers (0.15 square miles). This area has over 144 buildings, including a large palace, 6 stone monuments (stelae), 33 plazas, and various temples and noble homes. Other residential areas cover an additional 1.2 square kilometers (0.46 square miles).

By 2003, about 1,800 pieces of small figures had been found at the site.

The site is generally divided into three areas: the core, a North Zone, and an East Zone. The North Zone is separated from the core by a wide dip in the land that might have been a water reservoir.

The main buildings are grouped into five areas, A to E. Each group has at least one pyramid and several palace-like buildings. The main residential areas are in Groups A, B, and D, not including the royal palace in Group C. The main building groups are separated by lower areas that might have been used for intensive farming.

Two different building styles date to the last period of the city's occupation in the Late Classic. One uses well-carved stone blocks. The second style, thought to be from the Terminal Classic, uses thin, flat stones.

Building Groups

Group A

Group A is the largest group west of the city center. It has a 5.5-meter (18-foot) tall pyramid. This pyramid was badly damaged by looters, but the pits have been refilled. Six large rectangular palace-like buildings are west of this pyramid, up to 5 meters (16 feet) high. A plaza in Group A is formed by the pyramid and a palace.

Group B

Group B has a 7.7-meter (25-foot) high pyramid. It is about 90 meters (295 feet) south of a palace complex with two small plazas. The main complex in Group B looks a lot like a complex at Dos Pilas. The pyramid was looted, but the pits have been refilled. The tallest building in the palace complex is 4.5 meters (15 feet) high.

North of Group B are smaller residential groups. They were only used during the Late Classic period. Stela 2 is on a low platform west of the main pyramid.

Group C

Group C is the most important group at Motul de San José. It includes the Main Plaza, surrounded by pyramids and palaces. The tallest pyramid is 20 meters (66 feet) high. The three largest pyramids in Group C are built with thin, flat stones, a style likely from the Terminal Classic. Digs show Group C was used since the Late Preclassic (around 300 BC).

The Main Plaza in Group C is about 100 by 200 meters (328 by 656 feet). It's bordered by the Acropolis, twin pyramids, and the South Pyramid. It's the largest plaza at Motul de San José. Five stone monuments (stelae) are in the plaza, honoring Classic Period rulers. All have been badly damaged by bushfires.

The Twin Temples are on the east side of the Main Plaza. They are 17 and 18 meters (56 and 59 feet) high. Three stelae (Stelae 3, 4, and 5) were placed in front of them. The south pyramid has some damage from looters. Both pyramids likely had roof combs (decorative structures on top) and twin stairways.

The Acropolis is a large palace complex that likely housed the royal family. It covers over 83,000 square meters (893,400 square feet) and has six small plazas inside. Digs in the Acropolis found stucco floors, many pottery pieces, and fragments of stone, obsidian, bone, and shell. Among the finds were three painted pots, a flute, and a drum.

The South Pyramid is the tallest building at the site, 20 meters (66 feet) tall. It forms the south side of the Main Plaza. Stela 6 was found near this pyramid.

Group D

Group D is a complex residential area north of the twin pyramids in Group C. It has buildings around a plaza, including two palaces. A 5-meter (16-foot) pyramid is on the east side. A looters' trench in the pyramid showed earlier construction levels. Archaeologists believe looters plundered a high-ranking noble or royal tomb. Items found included painted pottery, jade beads, shell beads, and a stingray spine. Human bones in the tomb were painted red. This suggests the palaces in Group D were royal homes or for priests.

Group D was used from the Middle Preclassic to the Terminal Classic. During the Terminal Classic, a ritual was performed, and the northern building was abandoned. This ritual involved scattering trash and possibly burning the building.

Group E

Group E is the second largest group at Motul de San José. It is west of Groups C and D. It has two pyramids, 7 and 4 meters (23 and 13 feet) high. Both have been looted. Residential groups are south and east of the pyramids.

Two palaces in Group E have a different architectural style. Their doors have projecting corners. One structure has a vaulted room with a central bench. This different style might mean Group E was associated with different noble families.

Group E has a 200-meter (656-foot) long avenue called the North South Avenue. It has homes on the east side and a 1-meter (3-foot) high wall on the west.

Stone Monuments (Stelae)

Six stelae (carved stone monuments) have been found at Motul de San José. All are in Group C, with five in the Main Plaza.

Stela 1, from the 700s AD, is the first known mention of "Itza Chul Ahau" ("Divine Lord of the Itza"). It's on the west side of the Main Plaza. Its text describes a local lord becoming ruler under Tikal's king. Stela 1 also strongly suggests Motul de San José was the Late Classic Ik polity.

Stela 2 is west of the Main Plaza, in Plaza B. Teoberto Maler photographed it in the early 1900s. It shows king Yajawte' K'inich dancing. Its west side shows a figure in the "X-ray style," where a mask is cut away to show the face underneath.

Stela 3 is on the east side of the Main Plaza, north of Stela 4.

Stela 4 is on the east side of the Main Plaza, near the Twin Temples. It shows king Yajawte' K'inich dancing with one foot raised.

Stela 5 is also on the east side of the Main Plaza, south of Stela 4.

Stela 6 is on the south side of the Main Plaza, north of the South Pyramid. It was found in 1988, broken into many pieces. It seems to have shattered after Motul de San José was abandoned. The stela likely showed a ruler in rich clothing, dancing. It is very similar to Stela 1 from Dos Pilas.

Satellite Sites

Several smaller sites are located around Motul de San José:

| Name | Location | Coordinates | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Akte | 7 kilometres (4.3 mi) NW | 17°4′53″N 89°56′13″W / 17.08139°N 89.93694°W | |||

| Buena Vista | 3 kilometres (1.9 mi) SW | 17°0′1″N 89°54′52″W / 17.00028°N 89.91444°W | |||

| Chachaklum | 5 kilometres (3.1 mi) E | ||||

| Chak Maman Tok' (La Estrella) | 3.6 kilometres (2.2 mi) SW | ||||

| Chakokot | 2 kilometres (1.2 mi) E | 17°1′38″N 89°52′55″W / 17.02722°N 89.88194°W | |||

| Kantetul | 2 kilometres (1.2 mi) N | La Trinidad de Nosotros | 2.6 kilometres (1.6 mi) SE | 17°0′34.61″N 89°52′56.55″W / 17.0096139°N 89.8823750°W |

Akte

Akte is about 7.1 kilometers (4.4 miles) northwest of Motul de San José. It's known for its carved stone monuments. Akte's center covers 35 hectares (86 acres) and has 32 buildings on a 40-meter (131-foot) high hill. The main periods of use were the Late Preclassic and Late Classic. Akte might have been a rural administrative center or a royal estate.

Seven carved monuments have been found at Akte, which is unusual for a small site. If these monuments were originally placed here, it might mean Akte was not part of Motul de San José's kingdom.

Stela 1 is the best-preserved monument at Akte. It shows a standing "divine lord."

Buena Vista

Buena Vista is 3 kilometers (1.9 miles) southwest of Motul de San José. It's on a hilltop overlooking Lake Petén Itzá. Thirteen buildings have been mapped around a small plaza. The site was likely used from the Middle Preclassic to the Late Classic. Buena Vista has good soil and is currently used for farming.

The earliest pottery found here dates to the end of the Early Preclassic. This long history might be because it's close to hills rich in chert. Digs have found chert workshops for making tools.

Buena Vista has an older building style than Motul de San José. It uses platforms made of unworked stone. This difference might be due to different building periods.

Structure 1 is the East Pyramid. It's a 2.5-meter (8-foot) high Late Classic burial structure. From its top, you can see Lake Petén Itzá and the Twin Temples of Motul de San José.

Chachaklum

Chachaklum is 5 kilometers (3.1 miles) east of Motul de San José. It might have been part of the Motul de San José kingdom. It's a large site covering over 2 square kilometers (0.77 square miles) with over 141 buildings. Chachaklum has a small ceremonial center. It's in an area with poor soils, which is unusual for such a dense settlement.

Chachaklum was mainly used during the Terminal Classic period (900s and 1000s AD). However, it has a long history, starting in the Late Preclassic and continuing through the Late Classic.

Chak Maman Tok' (La Estrella)

Chak Maman Tok' is a very small site 3.6 kilometers (2.2 miles) southwest of Motul de San José. It has a few mounds overlooking Lake Petén Itzá. Even though it's small, it seems to have been an important center for making high-quality chert tools. It was very important to Motul de San José's economy.

Chakokot

Chakokot is 2 kilometers (1.2 miles) east of the Main Plaza. It covers 16 hectares (40 acres) and has 59 buildings spread around a small plaza on a 40-meter (131-foot) high hill. It was mainly used during the Late Preclassic and Late Classic periods. The soils at Chakokot are good for farming, and corn was grown there.

The Plaza at Chakokot is small. The largest building is a 10-meter (33-foot) tall temple.

Most homes at Chakokot have one or more bottle-shaped underground storage chambers called chultunob. Fourteen have been found. They were closed with stone lids, suggesting they stored dry goods, not water.

La Trinidad de Nosotros

La Trinidad is also known as Sik'u' in the Itza language. It is 2.6 kilometers (1.6 miles) southeast of Motul de San José, on the north shore of Lake Petén Itzá. It might have been a Maya port. The site has over 115 buildings. It was used from the Middle Preclassic to the Early Postclassic. It was very active during the Early Classic (around AD 350) and Late Classic (AD 650–830).

La Trinidad de Nosotros has been suggested as Xililchi, a settlement visited by conquistador Martín de Ursúa after the Spanish conquered the Itza capital Noj Petén in 1697.

The site has two areas. The core is on a hill 40 meters (131 feet) above the lake. The second area is along the lake shore. The core has at least 80 buildings around five plazas. Most buildings are homes, but La Trinidad has a lot of ceremonial buildings for a small site. It seems to have been an important port for trade with Motul de San José.

The ballcourt is in Group F. It is T-shaped, with 25-meter (82-foot) long sides. Its last construction phase was in the Late Classic. This ballcourt is similar to the one at Dos Pilas. No ballcourt has been found at Motul de San José itself, making this one special. Many artifacts were found near the ballcourt, including pottery, obsidian, and stone tools.

Various structures have been found in the port area, including walls, a possible breakwater, and a quay. The port seems to have been partly enclosed by an artificial peninsula.

Images for kids

-

Lady Wak Tuun of Motul de San José married Yaxun B'alam IV of Yaxchilán. Here she is depicted performing a bloodletting rite in AD 755. Yaxchilán Lintel 15, now in the British Museum.

See also

In Spanish: Motul de San José para niños

In Spanish: Motul de San José para niños

| Bayard Rustin |

| Jeannette Carter |

| Jeremiah A. Brown |