Ngarrindjeri facts for kids

The Ngarrindjeri people are the traditional Aboriginal Australian people who have lived for a very long time in the lower Murray River area, the eastern Fleurieu Peninsula, and the Coorong in southern South Australia. The name Ngarrindjeri means "belonging to men." It refers to a group of different but related Aboriginal communities. These groups included the Jarildekald, Tanganekald, Meintangk, and Ramindjeri. Over time, many of these groups came together, especially at Raukkan, South Australia (which used to be called Point McLeay Mission).

Some people, like Irene Watson, who is a descendant of these peoples, believe that the idea of one "Ngarrindjeri" identity was created by European settlers. They think that settlers grouped many different Aboriginal communities and families into one big group, which is now known as Ngarrindjeri.

Contents

Understanding the Ngarrindjeri Name

The name "Ngarrindjeri" was made popular by a missionary named George Taplin. He spelled it Narrinyeri. He used it to describe a group of different tribes, and it meant "belonging to people," as opposed to kringgari (which meant white people). The name suggests that those outside the group were not seen as fully human. Other names were used, but Taplin's name became widely known.

Later experts who studied cultures and people had different ideas about how these tribes were connected. Some thought it was a "reinvention of tradition," meaning the idea of a single big group might have been created later.

Ngarrindjeri Lands

The Ngarrindjeri lands stretch along the Coorong coastline. They go from Victor Harbor in the north to Cape Jaffa in the south. Inland, their lands reach just north of Murray Bridge. In some areas, the land is a narrow strip along the coast, but in the south, it extends further inland towards Coonawarra. The Ngarrindjeri lands also include the two large lower lakes of the Murray River: Lake Alexandrina and Lake Albert.

History of the Ngarrindjeri People

Ancient History

Archaeological digs, especially at a place called Roonka Flat, show that the Ngarrindjeri lands have been lived on for a very long time. People have been there since about 8,000 BC, right up until around 1840 AD. This site is very important for understanding Aboriginal burial practices before Europeans arrived in Australia.

After European Contact

European whalers and sealers started visiting the South Australian coast in the early 1800s. By 1819, there was a permanent camp on Kangaroo Island. These men sometimes took Aboriginal women from the mainland, especially from the Ramindjeri group.

Before British settlers officially arrived in South Australia, a smallpox sickness spread down the River Murray. This disease likely killed many Ngarrindjeri people. It changed their funeral customs, cultural practices, and how family groups lived and used the land. Old songs from that time talk about the smallpox coming from the east like a bright flash. In 1830, the first European explorers reached Ngarrindjeri lands and noticed that the people already knew about firearms.

By the time British settlement began in 1836, the Ngarrindjeri population was around 6,000 due to the smallpox epidemic. They are one of the few Aboriginal groups whose land was close to a capital city (Adelaide) who have survived as a distinct people. Many still live at the former mission at Raukkan.

Pomberuk, which means "crossing place" in Ngarrindjeri, was a very important site on the banks of the Murray River in Murray Bridge. All 18 of their clans (called lakinyeri) would meet there for special ceremonies. About 22 kilometers further down the river was Tagalang (Tailem Bend), a traditional trading camp where clans would gather to trade things like ochre, weapons, and clothes. In the 1900s, Tailem Bend became a government place where Ngarrindjeri people received food rations.

European Settlement and Changes

The Ngarrindjeri were among the first Aboriginal people in South Australia to work with Europeans on big projects. They worked as farmers, whalers, and laborers. As early as 1836, Aboriginal crews were working at whaling stations, and some boats were even fully operated by Aboriginal crews. The Ngarrindjeri helped process whale oil and were given meat, gin, and tobacco in return. They were often treated as equals in these early days.

As more Europeans settled in South Australia and moved onto Ngarrindjeri lands, the traditional campsite of Pomberuk remained until the 1940s. The last Aboriginal people living there were forced to leave in 1943 by the new landowners, the Hume Pipe Company. They were then moved by the local council and the South Australian government.

A senior Ngarrindjeri elder named Albert Karloan (Karloan Ponggi) fought to stay on his land. He traveled to Adelaide to get help, but he was given an eviction order. He returned to Pomberuk and sadly died the next morning in 1943.

Today, the Ngarrindjeri Regional Authority wants to rename Hume Reserve to Karloan Ponggi Reserve to honor the old people who fought to keep their traditions. They have a plan to protect and develop the site as a memorial and a place for learning about reconciliation.

Ngarrindjeri Language

The first study of the Ngarrindjeri language was done by a missionary named H.A.E. Meyer in 1843. He collected many words, mostly from the Ramindjeri dialect. George Taplin collected even more words from different dialects, and his dictionary had 1,668 English entries. Today, a modern Ngarrindjeri dictionary has 3,700 words. The Ngarrindjeri language is now grouped with other languages of the Lower Murray area.

Ngarrindjeri Culture

Dreaming Stories

Many important Dreaming sites are found along the River Murray. Near where the Murray River meets Lake Alexandrina is a place called Murungun, which is home to a bunyip spirit called Muldjewangk.

One famous Dreaming story tells of an ancestral hero named Ngurunderi. He chased a huge Murray cod fish named Pondi from a stream in central New South Wales. As Pondi tried to escape, its thrashing tail created the River Murray and the lagoons next to it. At Kauwira (Mannum), Ngurunderi forced Pondi to turn sharply south. The straight part of the river to Peindjalong (near Tailem Bend) happened because Pondi fled in fear after being speared in the tail. The two large sandhills of Mount Misery on Lake Alexandrina are called Lalangenggul. They show where Ngurunderi brought his rafts ashore to make camp. Ngurunderi then cut up Pondi at Raukkan, throwing the pieces into the water, and each piece became a different type of fish.

While there was a main Dreaming story, different family groups had their own versions. For example, some said Ngurunderi created the fish on the coast, while others believed it was where the river meets Lake Alexandrina, or where fresh water meets salt water. They also shared some Dreaming stories with tribes in New South Wales and Victoria.

The bunyip appears in Ngarrindjeri Dreaming as a water spirit called the Mulyawonk. This spirit would get anyone who took too many fish from the waterways or took children if they got too close to the water. These stories taught important lessons about caring for the land and its people, helping the Ngarrindjeri survive for a long time.

Customs and Relationships

The Ngarrindjeri have their own language group. They also have their own unique family customs and rituals that are different from surrounding peoples. This is partly because of their relationships with other groups. For example, they were sometimes in conflict with the Kaurna people to the west, who controlled red ochre. They also had issues with the Merkani to the east, who sometimes took Ngarrindjeri women.

However, the Ngarrindjeri had important friendly relationships with the Walkandi-woni (people of the warm north-east wind), which was their name for various groups living along the River Murray as far as Wentworth. These groups often met at places like Wellington, Tailem Bend, Murray Bridge, Mannum, or Swan Reach to share songs and hold ceremonies. In 1849, George Taplin saw about 500 Ngarrindjeri warriors gathered together.

Daily Life

Unlike most Aboriginal communities in Australia, the rich land of the Ngarrindjeri allowed them to live a semi-settled life. They would move between permanent summer and winter camps. One challenge for early European settlers was that the Ngarrindjeri would often rebuild their camps on land that Europeans wanted for farming.

In the early days of South Australia, laws were supposed to protect the land rights of Aboriginal people. However, these laws were often ignored by settlers who wanted to survey and sell the land without any problems.

Crafts and Tools

The Ngarrindjeri were known as excellent craftspeople. They used plants like bulrushes, reeds, and sedges for basket-weaving, making mats, and ropes. Trees provided wood for spears, and stones were shaped into tools. They were especially good at making nets. Records show they used nets over 100 meters long to catch emus. Settlers even said that the fishing nets made by the Ngarrindjeri were better than their own. These nets were made by chewing the roots of bulrush plants until only the strong fibers remained. Women would then spin these fibers into threads, and men would weave them into nets. Owning a net was seen as a sign of wealth.

Ngarrindjeri Food and Nutrition

The Ngarrindjeri people relied on the plants and animals around them for food and bush medicine. Before European settlement, the Fleurieu Peninsula had many swamps and woodlands. These areas were home to many birds, fish, and other animals, including snake-necked turtles, yabbies, ducks, and black swans. Plants like native orchids, guinea flowers, and swamp wattle were also important.

Europeans often praised the Ngarrindjeri for their cooking skills and efficient camp ovens, which can still be found in the River Murray area. Some easy-to-catch fish, birds, and animals were reserved by law for the elderly and sick. This shows how much food was available in Ngarrindjeri lands. In the early colony, Ngarrindjeri people would often offer to catch fish for the European settlers.

Many foods were subject to ngarambi (a type of taboo or prohibition). For example, eating their ngaitji (family group totems) was not always forbidden, but it depended on the family's rules. Some families would not eat their totem, while others could if it was caught by someone from a different family. Once an animal was dead, it was no longer considered ngaitji, which means "friend." A ngaitji was not sacred in the Western sense but was seen as a "spiritual advisor" to the family group.

Other foods were ngarambi based on how people felt about the species. Male dogs were friends and not eaten, while female dogs were not eaten because they were considered "unclean." Snakes were not eaten because of how their skin felt. Some birds that acted cruelly to other animals were ngarambi, and magpies were forbidden because they would warn other birds if they were being hunted. Some bird species were ngarambi because they were believed to be the spirits of people who had died. Birds also became ngarambi during nesting season.

Foods with supernatural rules were limited to bats, white owls, and certain foods that were only ngarambi for women or pregnant women. Young boys going through initiation were also considered ngarambi. Any food they caught or prepared was forbidden to all women, who were not even allowed to see or smell it. Breaking these rules, even by accident, could lead to physical punishments for the woman and her relatives. By the 1930s, many of these ngarambi rules were forgotten or ignored.

Ngarrindjeri Social Structure

According to George Taplin, there were eighteen land-based clans, or lakalinyeri, that formed the Ngarrindjeri "confederacy" or "nation." Each clan was managed by about a dozen elders called tendi. The tendi from each clan would then meet to choose a rupulli, who was the leader of the entire Ngarrindjeri confederacy. Taplin believed this was a central, organized government that managed eighteen separate areas.

Ngarrindjeri Clans (lakinyeri)

Taplin listed 18 lakinyeri. Each lakinyeri had its own nga:tji/ngaitji (totem or "friend"). Later, Alfred William Howitt, using Taplin's information, listed 20. Here are some examples:

| Clan Name | Location | Totem (ngaitji) |

|---|---|---|

| Ramindjeri | Encounter Bay | wirulde/tangari (wattle gum) |

| Tanganarin | Goolwa to the Coorong | manguritpuri (pelican) |

| Kandarlindjeri | West side of the Murray Mouth | kandarli (whale) |

| Pankindjeri | Coorong east of Lake Albert | kunnguldi (butterfish) |

| Kaikalabindjeri | Southern/eastern shores of Lake Albert | ngulgar-indjeri (bull ant) |

| Rangulindjeri | Western shore of Lake Albert | turiit-pani (dark-colored dingo) |

| Punguratpula | Western side of Lake Alexandrina around Milang | peldi (musk duck) |

Every member of a lakinyeri is related by blood. It is forbidden to marry someone from the same lakinyeri. Also, a couple cannot marry someone from another lakinyeri if they share a great-grandparent or a closer family member.

Later research by Norman Tindale and Ronald and Catherine Berndt in the 1920s and 1930s identified only 10 lakinyerar. Some clans might have disappeared or merged due to population decline after European settlement. Also, family groups within the clans sometimes used local dialects or their own family names for the clans, which caused confusion.

Ngarrindjeri Regional Authority

The Ngarrindjeri Regional Authority (NRA) is the main group that represents the Ngarrindjeri people today. It includes representatives from 12 Ngarrindjeri organizations and four other elected community members. Its goals are to:

- Protect and improve the well-being of the Ngarrindjeri people.

- Protect important cultural sites for the Ngarrindjeri people.

- Create better economic opportunities for the Ngarrindjeri people.

- Help with social welfare programs for Aboriginal people.

- Work towards Native Title over the traditional lands and waters of the Ngarrindjeri people.

- Make agreements and contracts with other groups on behalf of the Ngarrindjeri people.

- Manage land that is culturally important to the Ngarrindjeri people.

- Protect the intellectual property rights of the Ngarrindjeri people.

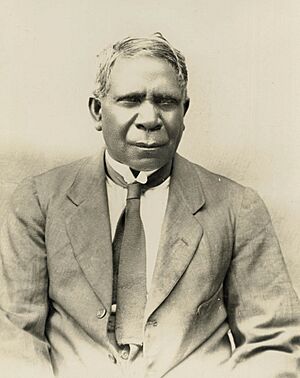

Notable Ngarrindjeri People

- Ian Abdulla (1947–2011), a famous artist.

- Poltpalingada Booboorowie (Tommy Walker), a well-known person in Adelaide in the 1890s.

- Ruby Hunter, a talented musician.

- Doreen Kartinyeri (1935–2007), an elder and historian.

- Natascha McNamara, an academic and activist.

- David Unaipon, an inventor and author, whose picture is on the Australian $50 note.

- James Unaipon, the first Aboriginal deacon.

- The Deadly Nannas, a musical group from the Murray Bridge area.

Some Ngarrindjeri Words

- kondoli (whale)

- korni/korne (man)

- kringkari, gringari (whiteman)

- muldarpi/mularpi (traveling spirit of sorcerers and strangers)

- yanun (speak, talk)

Animals No Longer Found in the Area Since Colonisation

- maikari: Eastern hare-wallaby

- rtulatji: Toolache wallaby

- wi:kwai: Pig-footed bandicoot

See also

In Spanish: Ngarrindjeri para niños

In Spanish: Ngarrindjeri para niños

| Bayard Rustin |

| Jeannette Carter |

| Jeremiah A. Brown |