Nicholas Miklouho-Maclay facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

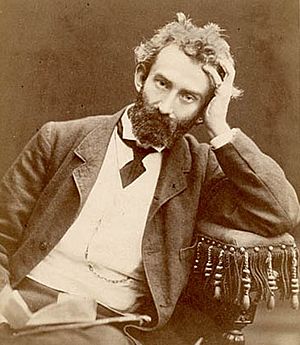

Nicholas Miklouho-Maclay

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Born | 17 July 1846 Rozhdestvenskoe, Novgorod Governorate, Russian Empire

|

| Died | 14 April 1888 (aged 41) |

| Nationality | Russian Empire |

| Alma mater | Heidelberg University, Leipzig University, Jena University |

| Known for | anthropological work in New Guinea and the Pacific |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Ethnology, Anthropology, Biology |

| Influences | Ernst Haeckel |

| Author abbrev. (botany) | Mikl.-Maclay |

| Author abbrev. (zoology) | Miklucho-Maclay |

Nicholas Miklouho-Maclay (Russian: Никола́й Никола́евич Миклу́хо-Макла́й; 17 July 1846 – 14 April 1888) was a Russian explorer, ethnologist, anthropologist and biologist. He became famous for being one of the first scientists to live among and study the indigenous people of New Guinea. These people had never seen a European before.

Miklouho-Maclay spent most of his life traveling. He did scientific research in the Middle East, Australia, New Guinea, Melanesia, and Polynesia. Australia became like a second home to him, and Sydney was where his family lived.

He was an important person in Australian science in the 1800s. He spoke out against the slave trade, also known as "blackbirding". This was when people were forced to work on plantations in Australia and other Pacific islands. He also opposed British and German countries trying to take over New Guinea.

While in Australia, he built the first biological research station in the Southern Hemisphere. He believed that all human races were equal. He was one of the first scientists to prove that different races did not belong to different species.

Contents

Early Life and Family Roots

Nicholas Miklouho-Maclay was born in 1846 in a temporary workers' camp in Russia. His father was a civil engineer working on the Moscow-Saint Petersburg Railway. His family had Ukrainian roots, tracing back to Zaporozhian Cossacks.

His ancestor, Stepan Myklukha, was a brave Cossack officer. He was honored by Empress Catherine II for his military actions. Nicholas wrote about his family:

My ancestors came originally from the Ukraine, and were Zaporogg-cossacks of the Dnieper. After the annexation of the Ukraine, Stepan, one of the family, served as sotnik (a superior Cossack officer) under General Count Rumianzoff, and having distinguished himself at the storming of the Turkish fortress of Otshakoff, was by ukase of Catherine II created a noble...

Nicholas's father, Mykola Myklukha, became an engineer. He was the first chief of the Moskovsky passenger railway station in Saint Petersburg. Sadly, he died in 1857 from tuberculosis. Before he died, he was fired from his job for sending money to a famous Ukrainian poet, Taras Shevchenko.

Nicholas's mother, Ekaterina Semenovna, had German and Polish family. After 1873, the family bought a country estate in Malyn, Ukraine. Nicholas had several brothers. One became a judge, another a geologist, and a third was a navy captain who died in battle.

Education and Scientific Training

In 1858, Nicholas started school in Saint Petersburg. He was arrested for taking part in student protests while at high school. A Russian writer, Aleksey Konstantinovich Tolstoy, helped him and his brother. In 1863, Nicholas started at St. Petersburg University. But he was expelled after only two months for "breaking the rules."

In 1864, he moved to Germany to continue his studies. He used a fake passport to leave Russia. He studied at different universities, including Heidelberg, Leipzig, and University of Jena. At Jena, he was taught by the famous German scientist Ernst Haeckel. Haeckel greatly influenced Nicholas's future work.

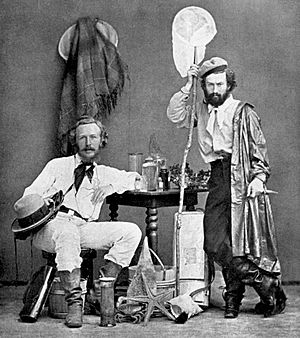

Nicholas was a brilliant student. Haeckel made him his assistant for a trip to the Canary Islands in 1866. There, Nicholas studied sharks and sponges. He even discovered a new sponge species, which he named Guancha blanca. He also became good friends with biologist Anton Dohrn. Together, they thought of the idea of having special research stations for scientists.

Life and Work in Australia

Miklouho-Maclay traveled from St Petersburg to Australia on a ship called the Vityaz. He arrived in Sydney on July 18, 1878. Soon after, he suggested creating a zoological center to the Linnean Society.

In September 1878, his idea was approved. The center was called the Marine Biological Station. It was built in Watsons Bay, near Sydney. This was the first marine biological research center in Australia.

Nicholas married Margaret-Emma Robertson, whose father was the Premier of New South Wales. His home in the Sydney suburb of Birchgrove is now a protected historical site because of him.

Studying People in New Guinea

Miklouho-Maclay lived in northeastern New Guinea for two years, between 1871 and 1880. During this time, he also visited the Philippines, the Malay Peninsula, and Australia. He returned to New Guinea again in 1883.

He lived among the native tribes there. He wrote detailed reports about their way of life and customs. These writings were very helpful for later researchers.

Views on Human Races

In the 1850s and 1860s, scientists often debated about human races. Some, like Samuel Morton, tried to argue that not all human races were equal. They even claimed that "white people" were naturally meant to rule over "colored" races.

Some scientists, including Ernst Haeckel, Nicholas's teacher, thought that culturally "backward" people like Papuans were "intermediate links" between Europeans and animals. Nicholas believed in Darwin's theory of evolution. However, he disagreed with these ideas about race.

He wanted to gather scientific facts to study the dark-skinned people of New Guinea. Based on his research into comparative anatomy, Miklouho-Maclay was one of the first anthropologists to reject the idea that different human races belonged to different species.

The famous writer Leo Tolstoy wrote to Nicholas in 1886:

You were the first to demonstrate beyond question by your experience that man is man everywhere, that is, a kind, sociable being with whom communication can and should be established through kindness and truth, not guns and spirits. I do not know what contribution your collections and discoveries will make to the science for which you serve, but your experience of contacting the primitive peoples will make an epoch in the science for which I serve i.e. the science which teaches how human beings should live with one another.

– Leo Tolstoy, to N. N. Miklhouho-Maclay, September 1886

Fighting Against Slavery

Nicholas Miklouho-Maclay was a humanist. This means he believed in the value and dignity of all people. He actively campaigned against the slave trade. He also fought against "blackbirding"—the practice of kidnapping people from Melanesian islands to work on plantations.

In November 1878, the Dutch government told him they were stopping slave traffic based on his suggestions. From 1879 onwards, he wrote many letters to Australian newspapers. He also wrote to Sir Arthur Gordon, a high official in the Western Pacific. He wanted to protect the land rights of his friends on the Maclay Coast of New Guinea.

Later Years and Legacy

In 1887, Nicholas left Australia and went back to St Petersburg. He wanted to show his work to the Imperial Russian Geographical Society. He took his young family with him.

Miklouho-Maclay was not well. Despite getting treatment, he died at age 41 in St Petersburg. He had an undiagnosed brain tumor. He was buried in the Volkovo Cemetery.

His wife and children returned to Sydney. The scientist's family received a pension from the Russian Empire until 1917. His travel journals were published in 1923. A large collection of his works was published in 1953.

Commemoration Around the World

Nicholas Miklouho-Maclay is remembered in the names of several species he discovered. These include the New Guinea tree Pouteria maclayana and the banana species Musa maclayi. The weevil Rhinoscapha maclayi was also named after him by his friend William Macleay.

Other species named after him are a wasp from New Guinea, Colastomion maclayi, and a scale insect, Dysmicoccus maclayi. An asteroid, 3196 Maklaj, discovered in 1978, was named in his honor.

In Australia, the Marine Biological Station he built is now a private residence. However, it is sometimes open to the public. A park in Birchgrove, Sydney, is named after him. A statue of Miklouho-Maclay was put up at the University of Sydney in 1996. The university also offers a special fellowship in his name.

A monument to Miklouho-Maclay was unveiled in Jakarta, Indonesia, in 2011. In Papua New Guinea, the area where he stayed is sometimes called the Maclay Coast. A street in Madang, Papua New Guinea, is named after him. Monuments have also been built near Bongu village in Madang Province.

In Russia, there is an N.N. Miklukho-Maklai Institute of Ethnology and Anthropology named after him. A street in Moscow and a museum in Okulovka also bear his name. A river passenger ship was named after him too. There is also a statue of him in Sevastopol. In Malyn, Ukraine, where his family lived, a monument to him stands.

Images for kids

-

Bust of Miklouho-Maclay, Macleay Museum at University of Sydney

-

Monument to Miklouho-Maclay in New Guinea

-

Monument near Bongu Village, Madang Province, New Guinea

-

Monument to Miklouho-Maclay in Malyn, Ukraine.

See also

In Spanish: Nikolái Miklujo-Maklái para niños

In Spanish: Nikolái Miklujo-Maklái para niños