North Western Area Campaign facts for kids

Quick facts for kids North Western Area Campaign |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Pacific War | |||||||

B-25 Mitchell bombers from No. 18 (NEI) Squadron near Darwin in 1943. This was one of three joint Australian-Dutch squadrons formed during the war. |

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

The North-Western Area Campaign was an air war fought between the Allied and Japanese air forces. It took place over northern Australia and the Netherlands East Indies (NEI) from 1942 to 1945. The campaign started with the Japanese bombing of Darwin on 19 February 1942. It continued until the end of World War II.

The Japanese attack on Darwin badly damaged the Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF) base. But the Allies quickly got back on their feet. Darwin was made stronger to prepare for a possible Japanese invasion. More airfields were built south of the town. By October 1942, the RAAF's North-Western Area Command had six squadrons. They were attacking Japanese bases in the NEI every day.

The Allied forces grew even more in 1943. United States Army Air Forces B-24 Liberator heavy bombers arrived. Australian and British Spitfire squadrons joined them. Australian and Dutch medium bomber squadrons also came. The Spitfires caused big losses for Japanese planes. The North-Western Area increased its attacks on Japanese positions. RAAF Catalina flying boats also successfully dropped mines in Japanese shipping lanes.

Contents

Japanese Air Power Near Australia

On 15 February 1942, a Japanese Kawanishi H6K flying boat took off from Ambon. Its mission was to follow the Houston convoy. This convoy had left Darwin without air protection. It had to return the next day, failing to help Allied soldiers on Timor. The Japanese flying boat found the convoy at 10:30 AM. It watched the ships for three more hours. When it was about 190 kilometers (118 miles) west of Darwin, the H6K tried to bomb the ships. It missed and turned back.

Soon after, an American Kittyhawk fighter spotted the flying boat. Lieutenant Robert Buel was the pilot. He attacked the Japanese aircraft. After a short fight, both planes caught fire. They crashed into the sea. This was the first air battle in the northern Australian air war.

This was the first of many Japanese aircraft shot down over northern Australia. For over two years, Japanese Army and Naval Air Forces watched northern Australia. They flew from Broome in the west to Horn Island in north Queensland. During much of this time, Australia was also bombed regularly. Land-based bombers were stationed just a few hours away from Darwin.

By early 1942, Japan had nearly 130 aircraft in the islands north-west of Darwin. This force included sixty-three Mitsubishi G4M (Betty) bombers. There were also forty-eight Mitsubishi A6M (Zero) fighters. Eighteen four-engined flying boats completed the group. These planes had fought in the Philippines campaign. They had also helped sink the British battleships HMS Prince of Wales and HMS Repulse. From bases in Java, Timor, Celebes, and New Guinea, the Japanese attacked Allied airfields. These included important ones at Townsville and Horn Island. Allied supply ships in the Arafura Sea and Torres Strait were also at risk.

The Air War Begins

First Attacks on Darwin

Darwin suffered the most from these powerful attacks. They began on 19 February 1942. The first two Japanese air raids on Darwin were very difficult for Australia. Allied leaders had not understood how strong the Japanese forces were. This was despite what happened at Pearl Harbor, Singapore, and Rabaul. Darwin's port had no fighter planes to defend it. The army had only two brigades. The harbor was full of ships, but only eighteen anti-aircraft guns protected them.

After the first Darwin air raid, there was a lot of confusion. People panicked because of rumors about a Japanese invasion. This was the biggest attack ever on mainland Australia. So, many historians focused only on these first surprise attacks. But these early raids were not isolated events. They were connected to later raids on Broome, Millingimbi, or Horn Island.

The Japanese air raids on Australia, though spread out, greatly affected General MacArthur's plans. He was the Allied commander in the South-West Pacific. The threat of invasion forced the Allies to defend northern Australia. This meant less focus on the New Guinea campaign at first. Darwin was attacked by a force as big as the one that hit Pearl Harbor. Yet, the main Allied effort was to defend Port Moresby.

MacArthur took the threat to northern Australia very seriously. He sent his first fighter squadron to Darwin, not Port Moresby. As more fighters became ready, they went to the Northern Territory. It was late April 1942 before Port Moresby had as many fighters as Darwin. Early warning radar systems were rare in 1942. But Darwin got them before Port Moresby.

Japanese Attacks in the North-Western Area

The Japanese kept attacking the North-Western Area. This also threatened the western approaches to New Guinea. This area was on the side of MacArthur's main forces. It had to be protected for his planned attacks to succeed. MacArthur knew the Japanese had much stronger air power in Timor, Java, and Celebes. By May 1943, Japan had almost sixty-seven airfields around Australia. A report in March 1943 said Japan could send 334 aircraft to north-west Australia.

This threat was so serious that eleven Allied squadrons were sent to defend the region. This included three of MacArthur's valuable heavy bomber squadrons. By August 1943, the air defenses grew. By July 1944, when the last Japanese plane was shot down over Australia, seventeen squadrons were defending northern Australia.

The war in northern Australia was more than just another Pearl Harbor. Pearl Harbor was a single attack on American warships. But attacks on northern Australia continued until late 1943. They hit many land targets and merchant ships. Darwin was probably the second most bombed Allied base in the South-West Pacific, after Port Moresby. For almost two years, the Japanese Air Force kept bombing. This slowed down the Allied war effort. It also caused a lot of worry among Australian civilians.

Unlike the war in New Guinea, the northern Australian war was mostly fought in the air. The only ground troops were anti-aircraft gunners. Both sides lost many aircraft and aircrew. In the end, Japan could not replace its losses. This forced them to stop their attacks there.

Not much has been written about the northern Australian air war. What has been published usually shows the Allied side. This began to change in the mid-1980s. Researchers started looking at original documents from Japan, Australia, and the United States.

Japanese aircraft losses in this campaign have not been studied in detail. Yet, they directly affected the outcome. By looking at these losses, we can better understand the air war. We can also get a more balanced view of this part of Australia's military history.

Japanese air operations against northern Australia had three main types: anti-shipping, reconnaissance, and bombing. Anti-shipping attacks were the first offensive actions. They mainly targeted Allied ships trying to resupply forces in Timor and Java. These attacks slowed down after 19 February 1942. But they started again in the Arafura Sea and Torres Strait in early 1943. Flying boats like the Kawanishi H6K (Mavis) and H8K (Emily) often did anti-shipping missions. Float-planes like the Mitsubishi F1M (Pete) or Aichi E13A (Jake) were also used.

Early Air Battles (February–April 1942)

The first plane destroyed in the northern Australian campaign was a Kawanishi Mavis. It was shot down 190 kilometers (118 miles) west of Darwin. This happened after it attacked the Houston convoy. Japanese anti-shipping operations began on 8 February 1942. This was almost two weeks before the first Darwin raid. The minesweeper HMAS Deloraine was attacked by a dive-bomber. This happened 112 kilometers (70 miles) west of Bathurst Island.

A week later, the Japanese 21st Air Flotilla sent five Mavises to find Allied convoys leaving Darwin. Four flying boats took off from Ceram at 2:00 AM. But the fifth, piloted by Sub-Lieutenant Mirau, was delayed. It took off at 4:00 AM. Mirau's plane was alone when it saw the Houston convoy at 10:30 AM. The convoy was heading for Timor. Mirau reported this by radio. He was told to keep following the convoy, which he did for three more hours. Before returning to Ceram, he tried to bomb the convoy from 4,000 meters (13,123 feet). He used 60-kilogram (132-pound) bombs, but missed. The crew was about to eat lunch when an American Kittyhawk attacked them.

Mr. M. Takahara was the flying boat's observer. He was one of only two crewmen who were not hurt. His memories, published in Japan, give a rare look into the Japanese air war. He described what happened after the Kittyhawk was seen: "The fighter came at them from behind. Takahara fired his cannon at it. At the same time, shots from the fighter tore through the flying-boat. When the fighter was very close, they saw white smoke from its tail. As the fighter dived to the sea, Takahara fired a whole magazine (50 rounds) into it. They saw the fighter hit the water... Takahara found his wireless operator was hit... the flying-boat, too, had flames from the door near the tanks... Takahara felt the shock as they hit, opened the door, and then passed out. He woke up in the water."

Takahara and the five other survivors were glad the Japanese Army Air Force used their information. The next morning, they saw twenty-seven Japanese bombers flying south to attack the convoy. The flying boat crew were captured on Melville Island. They were later held at Cowra, where they took part in the famous breakout in August 1944.

Anti-shipping attacks started again on 18 February. The Army supply ship, MV Don Isidro, was attacked by a Japanese plane. This happened north of the Wessel Islands in eastern Arnhem Land. It was not badly damaged and kept sailing west. Early the next morning, bombers returning from the first Darwin raid attacked it. This time, the Don Isidro caught fire and drifted ashore at Bathurst Island. MV Florence D. was another American Army supply ship in the area. A United States Navy Catalina from Patrol Squadron 22 was checking on the ship. Nine Zero fighters attacked the Catalina. The pilot, Lieutenant Thomas H. Moorer, survived. He wrote a detailed report. It is now seen as the first account of an air battle in northern Australia.

He wrote: "At 0800, February 19 I took off from Port Darwin... to patrol near Ambon... an unreported merchantman was seen off north cape of Melville Island... When about ten miles [sixteen kilometers] from the ship I was suddenly attacked by nine fighters... At that time I was flying downwind at 600 feet [190 meters]. I tried to turn into the wind but all fabric except starboard aileron was destroyed... There was no choice but to land downwind... the float mechanism was destroyed by gunfire... noise from bullets hitting the plane was terrible... I hit the water hard but after bouncing three times managed to land... The port waist gun was too hot to use but LeBaron... manned the starboard gun and fired back strongly... One boat was full of holes but [a second] boat was launched through the navigator's hatch. By this time the entire plane behind the wings was melting and large areas of burning gasoline surrounded the plane."

The Florence D. rescued the Catalina crew. Soon after, twenty-seven dive-bombers from the 1st Air Fleet attacked and sank the ship. This was the last anti-shipping attack of 1942. Japanese tactics changed by January 1943. They restarted anti-shipping operations in the Arafura Sea and Torres Strait. Small float-plane groups constantly patrolled the supply route to Darwin. They used Petes, Jakes, or (Kates). Japanese pilots often turned off their engines and dived from the sun. This meant the plane was not heard or seen until it dropped its bomb. The supply ship HMAS Patricia Cam was sunk this way near Wessel Island on 22 January 1943. The store ship Macumba was also sunk by float-planes at Millingimbi on 10 May. But a Spitfire from No. 457 Squadron shot down one of the float-planes.

These anti-shipping attacks did not stop Allied coastal supplies for long. Japanese flying boat bases at Taberfane and Dobo in the Aru Islands were attacked often in 1943. No. 31 Squadron RAAF Beaufighters carried out these attacks. Radar-equipped Beauforts from No. 7 Squadron RAAF also caused losses. By early 1944, the Japanese stopped their anti-shipping campaign. By this time, the Japanese navy had lost seven float-planes over northern Australia. Most of these were shot down by large twin-engined bombers like the Beaufort or Hudson.

Reconnaissance missions caused fewer Japanese aircraft losses. These were mainly done by Army Air Force Mitsubishi Ki46s (Dinahs). Kawasaki Ki-48s (Lilys), Mitsubishi Ki-21 (Sallys), C5Ms (Babs), and Zeros were also used. A naval reconnaissance plane was the first to appear over Darwin on 10 February 1942. Reconnaissance flights happened throughout the campaign. The last Japanese aircraft to fly over Australia in World War II was a Mitsubishi Ki21 (Sally). Lieutenant Kiyoshi Iizuka piloted it.

Reconnaissance flights were more common than bombing missions. Yet, only ten Japanese reconnaissance planes were destroyed by Allied fighters. When a reconnaissance plane appeared, it usually meant a bomber attack was coming. Reconnaissance flights were usually above 6,000 meters (19,685 feet). But Broome and Millingimbi, with weak anti-aircraft defenses, were checked from below 3,000 meters (9,842 feet). Sergeant Akira Hayashi flew a Bab when he first scouted Broome on 3 March 1942. The Bab was an old design even for 1942. This was probably its only use over Australia.

The nine Dinahs shot down over Australia likely belonged to the 70th Independent Squadron. This unit was part of the 7th Air Division, based at Koepang in Timor. The Dinah was very fast, reaching over 600 kilometers per hour (373 mph). Radar showed that Dinahs would cross the coast at high altitude. On the way back, they would dive, gaining speed. This helped them escape fighters and anti-aircraft guns. Japanese reconnaissance losses were acceptable given how often they flew. The 70th Squadron lost eight Dinahs. Four of them were lost on a single day (17 August 1943). Wing Commander C. R. Caldwell, Australia's top ace, shot down one of these planes. This was his last confirmed victory:

"I opened fire with all guns... strikes were seen on the enemy plane's left side, right engine, and tail. The right engine and body immediately caught fire. Some pieces of debris hit my plane... I flew behind it for several miles; it was burning in three places and trailing white smoke... The enemy plane seemed to try to level out for a moment. It hit the water 32 kilometers (20 miles) west of Cape Fourcroy. I photographed the splash with my camera gun. I flew low around the wreckage, seeing three bodies in the water. Two had partially open parachutes... One body was a large man in a black flying suit and helmet. He was lying spread-eagled on top of the water, face up. I thought he was still alive."

Losses from anti-shipping and reconnaissance were small. But nearly 160 Japanese aircraft were destroyed during the bombing attacks on Australia. These attacks were the most important part of the campaign. They also caused the most discussion. The bomber attacks caused most Japanese aircraft losses over Australia. They also had the biggest impact on the Allied war effort. Because of these Japanese bomber attacks, the United States Fifth Air Force had to send fighters and heavy bombers to the Northern Territory. This was at a time when they needed them elsewhere.

General MacArthur, the Allied Commander, told his air force commander, General Kenney, to prepare. Squadrons might need to move quickly to airfields around Torres Strait and in the Northern Territory. This would happen if Australia was threatened with invasion. To help these plans, the RAAF was ordered to build airbases quickly. These stretched from Truscott Airfield in the west to Jacky Jacky (Higgins Field) in north Queensland. The RAAF became so busy patrolling the Australian coast. By April 1943, it had more active squadrons in Australia than in the front lines in New Guinea.

These operations targeted land bases like Townsville, Horn Island, Fenton, and Millingimbi. The Japanese bomber attacks started on 19 February 1942. They ended on 12 November 1943. The last raids were against Darwin and Fenton. The Naval Air Force provided most aircraft for these attacks. But the Army Air Force also took part in at least two raids (19 February 1942 and 20 June 1943).

Betty bombers from the Kanoya and 753rd Air Corps were used most often. Kates, Sallys, Lilys, Mitsubishi G3Ms (Nells), Aichi D3As (Vals), and Nakajima Ki49s (Helens) were also used less often. The raids on Townsville and Mossman in July 1943 were different. Emily flying boats from the 14th (Yokosuka) Air Group carried them out. These planes flew from Rabaul, New Britain, a very long distance.

Bombers flying in daylight were always joined by Mitsubishi Zero fighters. These were called Haps, Hamps, or Zekes. Protecting the bombers was costly. Almost as many fighters were destroyed as bombers. The Zeros in the first Darwin raid were from the 1st Air Fleet. But the fleet had to leave the area after 19 February. Then, the 3rd, 4th, and 202nd Air Corps shared the job of escorting bombers. The first raids on Darwin, Broome, and Townsville have been described elsewhere. This article will focus on the bomber attacks on Darwin after February 1942.

Darwin was bombed sixty-four times. Each attack followed one of five patterns, switching between day and night. For months, Japanese air forces used the same attack method. This gave the Allies many chances to guess when and where the next attack would be. The Japanese became so predictable. One person wrote after the raid on 31 March 1942: "This is getting boring – the same. A small change this time, though, because they also came over at 10 p.m."

These comments were made during the first phase of attacks. The raiding force usually had seven bombers and at least as many fighters. The last of these raids, led by Lieutenant Fujimara, was on 5 April 1942.

Mid-War Attacks (April–December 1942)

The attack pattern changed a lot on 25 April that year. The 753rd Air Corps, led by Lieutenant Commander Matsumi, arrived over Darwin. They had twenty-four bombers and fifteen fighters. This turned out to be one of the most costly raids of the war. Thirteen aircraft did not return. The 23rd Air Flotilla could not afford such high losses. By mid-June, they had to stop large daylight raids.

Japanese aircraft strength on Timor, Bali, and Ambon was reported to be fifty-seven fighters, sixty-nine bombers, and four observation planes. There were more planes at Kendari. Until then, the Japanese had been very consistent. Most flights arrived over the target in the early afternoon. But when attacks started again in late July, after a six-week break, the bombers arrived at night. Most groups were much smaller. For six nights in a row, starting 25 July, small three-plane groups bombed the city. The attacks were all from over 6,600 meters (21,654 feet). The damage was very small.

These night attacks caused little physical damage. But they did make Darwin's people feel down. A Civil Aviation official noted: "We waited for the fifth raid of 27 bombers in a row with a sick feeling. We couldn't stop looking at the burning tanks. The town was empty except for a few people like us whose work kept them there. The raid didn't happen. I think it was the worst day of my life so far, just waiting for something that didn't happen."

The Japanese later used this tactic well. They kept sending small, unescorted groups at night. In other parts of the Pacific, these lone planes would stay overhead for hours. They would drop a bomb now and then to keep people from sleeping.

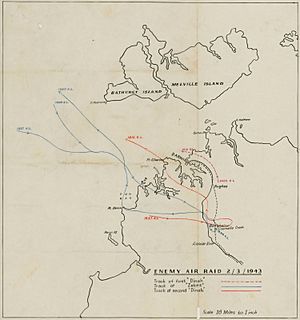

The night bombing pattern continued for the next six months. On 2 March 1943, they switched back to daylight operations. Lieutenant Commander Takahide Aioi's force of sixteen Zeros escorted nine Betty bombers. They raided the airfield at Coomalie.

The 23rd Air Flotilla, based at Kendari in the Celebes, was ordered to attack Darwin and Merauke monthly. These monthly attacks continued until 13 August. Then, the method changed again. The army's 7th Air Division had moved from Ambon to Wewak. This left the 23rd Air Flotilla to continue the campaign. The bombers kept coming at night until 12 November 1943. That was the very last time Darwin was attacked. Night bombers were not accurate, but they were rarely caught by fighters. Only twice in the whole bombing campaign did Allied fighters destroy Japanese bombers at night. Squadron Leader Cresswell destroyed one Betty bomber on 23 November 1942. Flight Lieutenant Smithson (457 Squadron), with searchlights, had destroyed two Betty bombers earlier on 12 November.

George Odgers wrote in his history of the Royal Australian Air Force. He said the need to move parts of the 23rd Air Flotilla finally made Japan stop attacking northern Australia.

The Japanese Naval Air Service lost many planes around Rabaul and the Northern Solomons. This forced them to move squadrons. One 36-aircraft fighter squadron from the 23rd Air Flotilla went to Truk in December. A 36-aircraft bomber squadron went to Kwajalein in the Central Pacific. They were waiting for the American fleet to advance.

The defense of northern Australia was a team effort. It involved the RAAF, the United States Army Air Forces (USAAF), the British Royal Air Force (RAF), and the Netherlands East Indies Air Force (NEIAF). However, the RAAF, RAF, and NEIAF could not help much until late 1942. The RAAF had some Wirraway trainers and Hudson medium bombers in the region in early 1942. But these were not good for the type of fighting the Japanese used.

The northern air war was mainly a fighter conflict. Kittyhawks and Spitfires fought against Zeros and strong Betty bombers. The Kittyhawks of the United States 49th Fighter Group did most of the early fighting. They eventually shot down almost half of the Japanese aircraft over Australia. The 49th Group also created the diving-pass attack system. This became the standard for all Allied fighters in the North-Western Area. The Japanese often arrived at over 6,600 meters (21,654 feet). The Allies' best defense was their early warning radar network. It could spot incoming groups up to 240 kilometers (130 nautical miles) away. Allied fighters were usually less agile than the Zero. They still had to climb fast to attack the Japanese from above.

The fast climb tactic used throughout the war limited the fighters' flight time. Allied planes often had to end their fights early. Ninety-two percent of all Japanese aircraft shot down over northern Australia were by Kittyhawks and Spitfires. The other thirteen planes were destroyed by anti-aircraft fire, Beauforts, Hudsons, or Beaufighters.

Most Japanese losses happened during daylight attacks on targets in the Northern Territory, especially Port Darwin. However, more than half these attacks happened at night. Allied fighters, without air-to-air radar, usually could not stop their attackers then.

The Americans were also at a big disadvantage when Japan first attacked Darwin. Since 15 February 1942, the 33rd Pursuit Squadron had been patrolling north-west of Darwin. But on 19 February, its planes were scheduled to fly to Timor. Ten of the squadron's P-40s had taken off for Koepang around 9:00 AM. But they had to return half an hour later due to bad weather. So, it was more luck than good planning that Darwin was not completely unprotected during the first Japanese air attack. The American Kittyhawks could offer little resistance to the 1st Air Fleet. It arrived over Darwin unseen and in huge numbers. The Japanese pilots were also experienced fighters. Most American pilots were very new, some with only twelve hours of experience in combat planes.

Nine Kittyhawks were destroyed quickly. Only Lieutenant Robert Oestreicher managed to land his bullet-ridden P-40 ("Miss Nadine" #43) safely. Oestreicher was the only American pilot to shoot down Japanese planes in this battle (he was credited with two). His report describes that morning: "After flying among the clouds for about half an hour, I saw two series 97 dive bombers with fixed landing gear. They were heading for Batchelor Field. I intercepted them at about 1,500 feet [approximately 500 meters]. I fired and saw one burst into flames and go down. The other was smoking slightly as he headed for the clouds. I lost him in the clouds."

Later that afternoon, a report came that a coast artillery battery found both planes within 1.6 kilometers (1 mile) of each other. These were the first confirmed air victories on Australian soil.

The Japanese 1st Air Fleet is thought to have lost at least five aircraft during the first Darwin raid. Australian anti-aircraft gunners shot down one Zero and one bomber. A second Zero was later found crash-landed on Melville Island. This last plane was mostly intact. It gave Allied intelligence officers their first chance to study the Zero's amazing performance. A detailed look at the plane showed important things like its maximum range and firepower. It also showed weaknesses, like no fuel tank protection, pilot armor, or armored glass. It was also found that the Japanese used Swedish cannons and American compasses, propellers, and machine guns. The Zero was starting to look vulnerable.

Discoveries like these were handled by the Technical Air Intelligence Unit (TAIU). This American unit, based in Brisbane, had a sub-unit in the North-Western Area by October 1942. It was in charge of studying Japanese aircraft. The unit's Australian representative, Pilot Officer Crook, often competed with souvenir hunters for access to Japanese plane wreckage. Crook's main job was to examine enemy wreckage. He collected data plates that souvenir hunters missed. This helped him track changes in weapons, crew size, camouflage, and engine design. By comparing serial numbers and production dates, they could also guess how many of each plane type were made.

Intelligence data appeared in strange ways. For example, in September 1942, members of 77 Squadron on leave found two briefcases with Japanese markings. They contained heated flying suits and other personal gear. But examining crash sites often gave the most information. The unit's biggest success was saving Betty T359. This was the first Japanese plane shot down over Australia at night in air-to-air combat. The plane crashed on Koolpinyah Station and was found mostly intact. Looking at the wreckage showed that the Betty carried nine crewmen, not seven, as thought before.

On 27 February, Lieutenant Oestreicher was ordered to fly south. He was to report to the 49th Fighter Group at Bankstown. General MacArthur had agreed that the 49th Fighter Group, led by Colonel Paul Wurtsmith, should go to the Northern Territory. But Darwin was left unprotected for almost four weeks. The first parts of the group arrived on 14 March. Meanwhile, the Japanese had started attacking Broome, Wyndham, and Horn Island. The Allies had no fighter defenses at Broome or Wyndham when Japanese fighters attacked on 3 March 1942. Twenty-four Allied aircraft were destroyed in fifteen minutes. Only one Zero, piloted by Chief Air Sergeant Osamu Kudo, was shot down by anti-aircraft gunners.

However, the Japanese faced strong resistance when they first attacked Horn Island on 14 March. Eight Nell bombers and nine Zeros arrived at 1:00 PM. Nine P-40s from the 7th Fighter Squadron intercepted them. This squadron was passing through on its way to Darwin. This was the first time the Japanese Air Force met strong fighter opposition over mainland Australia. The result was not good for the Japanese. The Americans shot down four Zeros and one bomber. One American plane was destroyed, and one was damaged. Second Lieutenant House, Jr. shot down two of the Zeros. Although Horn Island was attacked many times, the Japanese always avoided Allied fighters after this.

Kittyhawks of the 49th Fighter Group arrived in Darwin by mid-March. On 22 March, they made their first interception. Nine bombers, three Zeros, and one reconnaissance plane flew 300 kilometers (186 miles) inland to Katherine. They dropped bombs from high altitude. An Aboriginal person was killed, another wounded, and the airfield was damaged. The 9th Fighter Squadron only destroyed one Nakajima reconnaissance plane. But they helped pioneer the use of early warning radar in the South-West Pacific. Early warning radar was the most important factor in the northern Australian air war. Without enough warning, Allied fighters could not defend well against enemy groups. These groups always arrived over the mainland at very high altitudes. The 22 March raid was the first successful radar-controlled interception of the war. The CSIR's experimental radar station at Dripstone Caves, near Darwin, detected the incoming group from about 130 kilometers (81 miles) away. This proved how useful radar-controlled interception was to a doubtful military and civilian community.

Radar was no longer a new invention to be doubted. It was a valuable weapon. Belief in its power grew fast. Radio physicists knew that air warning sets did not cover areas near the ground. This was because of radio waves reflecting from the earth. If the Japanese had known this, they could have flown low. They would have gotten very close to the target before being detected. Luckily for Britain, even German pilots did not know this trick early in the war. German pilots learned it later. Long after the Darwin raids, they passed the trick to the Japanese. But by then, their air strength was almost gone. The Americans failed to intercept during the next five raids. On 2 April, bomb fragments hit the Shell oil refineries in Harvey Street. This caused 136,000 liters (36,000 gallons) of aviation fuel to be lost. Two days later, however, the Kittyhawks were ready. Seven bombers and six fighters attacked the civilian airfield at Darwin. The 9th Fighter Squadron destroyed five bombers and two Zeros. They lost only one of their own planes and damaged two. This battle greatly helped restore confidence in the struggling community. Second Lieutenants John Landers and Andrew Reynolds each destroyed two aircraft in this fight.

The anti-aircraft defenses also did a great job. The Australian 3.7-inch (94 mm) guns at Fanny Bay shot down two enemy bombers. One person watching described it: "Day of days. Our first win. Seven bombers appeared with several fighters. As the bombers came over the point, the very first two shots from the A.A. burst just behind the group. They got five of the seven bombers. One blew up right away. Another, badly burning, screamed down to the ground. The others, with amazing discipline, tried to stay in formation. I saw a Jap jump out of one of the burning machines – just a small black dot. His parachute opened, but a burning piece of plane fell on it. The Jap fell fast and landed just on the other side of the airfield."

Equally dramatic were reports the next day of "enemy fighters flying at about 400-500 feet with American markings." Gunners at the oval "reported clear Zero features with USA markings." The fact that these reports were made separately and from close range makes them believable.

The anti-aircraft guns were important throughout the campaign. They made sure bombers stayed at a high altitude. This made accurate bombing very hard. The Australian gunners were very effective. They shot down a total of eight enemy aircraft. Until 4 April, Darwin had only one squadron of American fighters. The city felt less defenseless when more help arrived two days later. This was the 7th Fighter Squadron. The 8th Fighter Squadron also arrived by 15 April. This gave the 49th Fighter Group its full sixty aircraft. Never again were the Allies outnumbered as they were at the start of the war.

The group repeated its earlier successes on 25 April. It destroyed thirteen enemy aircraft from a group of twenty-four bombers and fifteen fighters. Second Lieutenant James Morehead of the 8th Fighter Squadron shot down three of the bombers. First Lieutenant George Kiser did the same two days later. He also destroyed two bombers and one Zero. This was the last raid for some time. The 23rd Air Flotilla then stopped attacking Australia for almost six weeks. The 49th Fighter Group had done very well so far. Before May, it had lost eight P-40s and three pilots. It had destroyed thirty-eight Japanese planes and an estimated 135 crewmen. The 49th's combat record was the only good news in the Allied war effort, which was still mostly defensive.

The 49th Fighter Group had been fighting for over two months. On 28 May, the British prime minister announced he was sending three Spitfire squadrons to Australia. These were No. 54 Squadron (RAF) and two Empire Air Training Scheme squadrons, Nos 452 and 457. Both had formed in Britain in June 1941. The plan was for each squadron to get sixteen aircraft at first. They would also get five replacement aircraft per squadron each month. Unfortunately, the first forty-two Spitfires were sent to the Middle East. This happened after Tobruk fell on 21 June. Almost four months passed before the second seventy-one Spitfires arrived in Australia.

Large daylight raids started again on 13 June and continued for four days. During the last of these raids, on 16 June, the 49th Fighter Group had its first big setback. It lost five Kittyhawks but destroyed only two enemy aircraft. The Americans still had something to celebrate. Second Lieutenant Reynolds had shot down his fifth Japanese aircraft in northern Australia. Reynolds became the first ace of the Australian campaign. Five other Allied pilots would also become aces by the time the campaign ended in July 1944. It is not known if any Japanese pilots became aces in this area.

The bombers arrived at night in July. This left the 49th Fighter Group unable to do anything but watch. The Japanese attacks spread out towards the end of the month. They included Port Hedland in Western Australia and Townsville in north Queensland. Port Hedland was not very important. But Townsville was the largest aircraft depot in northern Australia. It was also a key stop for planes going to New Guinea and the Central Pacific. This made the air war more real for Australians. For three nights from 25 July, Emily flying boats from the 14th (Yokosuka) Air Group bombed Townsville. Six American Airacobras from the 8th Fighter Group were alerted and airborne. This happened when the enemy was still 80 kilometers (50 miles) away. The Emily managed to drop its bombs and avoid being caught, despite these preparations. The Yokosuka Air Group returned the next night, encouraged by its success. This time, however, Emily number W37 was intercepted by two Airacobras from the 36th Fighter Squadron. They hit the huge flying boat many times. It seemed to escape without serious damage. An Allied radio operator later heard a message saying W37 had returned to Rabaul.

The radar station at Kissing Point in Townsville detected the enemy flying boats from far away. The RAAF badly needed an early warning radar network. By early 1942, the Australian Radiophysics Laboratory was asked to change some SCR268 anti-aircraft gunnery sets. These had arrived in Australia after the Americans left the Philippines. The first set changed this way was put up at Kissing Point. In July 1942, it gave an amazing one-hour-fifty-minute warning of an approaching enemy aircraft.

Such successes did not happen every day. At Exmouth Gulf in Western Australia on 24 September 1943, a group of birds on top of the antenna caused an air raid alert.

The 23rd Air Flotilla had restarted its daylight bombing campaign against Port Darwin. The 49th Fighter Group had early model Kittyhawk P-40Es. These were not as good as the agile Zero fighters. The Americans quickly realized their best defense was to dive through the enemy group. They knew the Zero could not follow at the same speed. On 30 July, the 49th showed it could get good results. This was if its Kittyhawks had the height advantage. On this day, Darwin's twenty-sixth air raid, the Americans had plenty of warning. So they could attack the enemy from above. They destroyed six bombers and three fighters, losing only one P-40. Second Lieutenant John Landers became the group's second ace. He had already destroyed three enemy aircraft in an earlier fight.

The next day, Port Moresby was raided for the seventy-seventh time. But the groups that attacked Darwin were generally much larger than those attacking Port Moresby. As late as September 1943, the 23rd Air Flotilla could still gather thirty-seven aircraft. In New Guinea, Japanese attacking groups became smaller as the war went on.

The first Australian reinforcements arrived in August 1942. Twenty-four Kittyhawks from No. 77 Squadron started operations at Livingstone. The squadron's arrival happened during a time of less enemy activity. It stayed in the region until early 1943. But it later left for Milne Bay without ever fighting the Japanese equally. The squadron's commander, Wing Commander Cresswell, did have one notable success. He shot down a Betty bomber from the Takao Air Group on the night of 23 November 1942. This was the first successful night interception of the northern Australian war.

No. 77 Squadron arrived in the Northern Territory just as the experienced American 49th Fighter Group was leaving. They had been fighting for five months. The group fought its last battle on 23 August. A very large enemy force of twenty-seven bombers and twenty-seven fighters tried to bomb the Hudsons at Hughes Field. Twenty-four Kittyhawks from the 7th and 8th Fighter Squadrons intercepted the group. They shot down fifteen Japanese aircraft, losing only one P-40. This later became the most successful battle of the entire campaign. It also gave the group its third ace, First Lieutenant James Morehead. He shot down two Zeros over Cape Fourcroy on Melville Island. The group left northern Australia with a total of seventy-nine Japanese aircraft destroyed. This cost them twenty-one Kittyhawks (and two damaged).

The Americans left at the same time replacement fighters arrived from Britain. These arrived in Sydney in October. This was lucky for the Allies. It was a time when the 23rd Air Flotilla was less active. No. 76 Squadron also arrived at Strauss in October. But like No. 77 Squadron, they left soon after, without much combat.

No. 31 Squadron's arrival at Coomalie that same month was a turning point. Until then, Allied air forces had been fighting defensively over their own bases. The arrival of Beaufighters gave the Allies a powerful weapon. They could now attack the enemy in their own territory. Mitchells and Hudsons had been attacking almost from the start of the war. But the Beaufighters of No. 31 Squadron were designed only for ground attacks. They greatly increased the enemy's losses.

Later Battles (January–November 1943)

The Spitfires (secretly called "Capstans") arrived from Britain the previous month. By late 1942, they had finished training in Richmond, New South Wales. They were regrouped under No. 1 Fighter Wing (RAAF). Group Captain Walters commanded the wing. Wing Commander Caldwell, Australia's top ace, was the wing leader. The wing moved to the Northern Territory in January 1943. No. 54 Squadron was based at Darwin, No. 452 at Strauss, and No. 457 at Livingstone. No. 18 Squadron (NEIAF) also arrived that month. This showed the shift to attacking the enemy.

The wing had barely started operations when it got its first victory on 6 February 1943. Flight Lieutenant Foster of No. 54 Squadron was sent to intercept an incoming Dinah. He shot it down over the sea near Cape Van Diemen.

This first excitement was followed by almost four weeks of quiet. Then, on 2 March, nine Kates and sixteen Zeros made a daylight attack on the No. 31 Squadron Beaufighters at Coomalie. Caldwell led No. 54 Squadron in a successful interception. He personally shot down his first Zero and a Kate bomber. The Japanese lost three aircraft in total. No Spitfires were shot down, but one Beaufighter was destroyed on the ground (A19-31). Five days later, No. 457 Squadron got its first victory. Four aircraft were sent to intercept Japanese planes reported over Bathurst Island. They were ordered to 4,500 meters (14,764 feet). They found a Dinah heading home over the sea about twenty-five kilometers (15.5 miles) from Darwin. Flight Lieutenant MacLean and Flight Sergeant McDonald each attacked twice from close range. The enemy plane plunged into the sea, burning fiercely.

The wing had its first big fight with the Japanese on 15 March. All three Spitfire squadrons intercepted a very large force. It had twenty-two Bettys escorted by twenty-seven Zeros. Using the European tactic of dogfighting, the Spitfires shot down six Bettys and two Zeros. They lost four of their own aircraft. However, the bombers did hit six oil tanks, setting two on fire. Squadron Leader Goldsmith, who destroyed two aircraft in this fight, later wrote in his log-book: "Fired at a Hap while his No. 2 came around behind me. Knocked pieces off wing, was hit in tail wheel and wing root. Followed bombers 128 kilometers (80 miles) out to sea, attacked from out of the sun. Got a Hap on the way down, made two attacks on Betty which broke formation. Landed with 14 liters (3 gallons) petrol, tail wheel broke off when I touched down."

Goldsmith's note about having only three gallons of fuel was a warning that was not heeded. The 49th Fighter Group had learned that nothing was gained by dogfighting with a Zero. This type of combat used too much fuel. If not controlled, it could lead to running out of fuel. Kittyhawk pilots had developed the diving-pass technique. They avoided close combat whenever possible.

The Spitfires kept using the dogfighting technique until 2 May. Then, five aircraft had to make emergency landings because they ran out of fuel. Three more Spitfires made emergency landings due to engine failure. All but two of these eight planes were later recovered. At the time, it looked like the wing had lost thirteen aircraft. The fact that all the bombers reached their target without loss made the situation seem much worse. To make things worse, the press got the casualty figures. They made a big deal about it being the first time heavy losses were reported.

The Advisory War Council had to order an official investigation. They asked for a special report from the Chief of Air Staff. As a result, the Spitfires were fitted with drop-tanks. Dogfighting was banned completely.

The Japanese 7th Air Regiment met a more disciplined enemy when it next attacked Darwin on 20 June. The wing achieved its best result. It shot down fourteen enemy aircraft while losing only three Spitfires. It was during this fight that Wing Commander Caldwell, already an ace from Europe, shot down his fifth Japanese aircraft.

The arrival of the USAAF 380 Bomb Group in the Northern Territory did not go unnoticed by the enemy. On 30 June, they switched their attention to Fenton, where the Liberator B-24s were based. The long-range Liberator attacks were so important. The Japanese now focused almost all their attacks on Fenton. The American airbase remained their main target for all future bombing attacks. This continued until the last Japanese raid on 12 November 1943.

The Liberators, because of their great range and bomb-carrying ability, were making the most effective contribution from the North-Western Area. Their location in the Northern Territory allowed them to hit targets far behind Japanese lines. These were out of reach for other Fifth Air Force bomber groups in New Guinea. These actions helped MacArthur's advance along the north New Guinea coast. They destroyed bases and forced the enemy to keep defenses far back, weakening the front lines. The Spitfires later shot down two more Dinahs. This brought the wing's total to seventy-six, slightly less than the 49th Fighter Group. No. 1 Fighter Wing had lost thirty-six Spitfires and had nine others damaged during the war.

Elsewhere, far east of Darwin, No. 7 Squadron (RAAF) also started to build an impressive record. No. 7 Squadron's Beauforts regularly patrolled the western approaches to Horn Island. They aimed to protect the vital shipping lanes through the Torres Strait. The Australian-built Beaufort Mk VIIIs had ASV (air-to-surface vessel) radar. On 18 June, aircraft A9-296, piloted by Flying Officer Hopton, made the first successful radar interception in the Australian war zone. The crew of A9-296 saw an enemy plane on its radar screen about ten kilometers (6.2 miles) away. This turned out to be a Jake float-plane. The Beaufort attacked it, and it crashed into the sea.

No. 7 Squadron later made two more successful interceptions. One of these must be the war's strangest combat. Flying Officer Legge was flying Beaufort A9-329 on 20 September 1943. He saw a 'Jake' 68 kilometers (42 miles) west of Cape Valsch and attacked it. The enemy plane made an emergency landing in the water, and the pilot dived overboard. Legge tried to bomb the 'Jake' in the water but missed. But the Beaufort came down to 30 meters (100 feet). The navigator fired his nose gun, hitting the enemy aircraft. The 'Jake' burst into flames. The Allied defense of northern Australia was a success. Allied air forces destroyed 174 aircraft in twenty-nine months after February 1942. They lost only sixty-eight Kittyhawks and Spitfires themselves. Japanese personnel losses were much higher. More than half the aircraft lost by the Japanese were bombers, usually Bettys, which each carried seven crewmen.

Results of the Campaign

The Japanese Air Force never reduced its attacks, despite these heavy losses. Darwin was attacked by large enemy groups as late as September 1943. The Northern Territory was still being bombed even after raids on Port Moresby had stopped. The Japanese Air Force also had some success. They kept attacking Australia while being on the defensive in most other war areas.

The damage from these attacks was relatively small. But the cost to the Allies was significant. Their planned attacks were delayed, and resources were moved, especially in 1942. The northern Australian air war could be called a "thorn in MacArthur's side." It was never completely crippling, but it was always a worry. In the end, the fight for air control over northern Australia was decided in the skies over Rabaul and the northern Solomons. The Japanese Naval Air Force suffered heavy losses there. This forced them to move aircraft from the 23rd Air Flotilla. Similarly, the Japanese army's 7th Air Division was also moved to make up for losses elsewhere in the Pacific.

The northern Australian air war will always be seen as an important, rather than a crucial, battle. There were no clear winners or losers. Yet, for all Australians, then and now, this event will always be remembered as a turning point in Australian history. Australians had become too comfortable after 154 years of peaceful settlement. They believed their isolation would keep them safe from foreign attacks. For most people in Australia in February 1942, the war was still an abstract idea. It involved foreign people, places, and ideas. But on 19 February, World War II became a reality for all Australians. It destroyed the idea that Australia was untouchable forever.

| Date | Target | Allied losses | Japanese attacking aircraft | Japanese losses |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 15 February 1942 | Houston convoy | 1 x P-40E | 1 x Kawanishi H6K | 1 x Kawanishi H6K |

| 19 February 1942 (AM) | Darwin | 4 x PBY-5 10 x P-40E 1 x C-53 |

71 x Aichi D3A 36 x Mitsubishi A6M2 81 x Nakajima B5N |

3 x Aichi D3A 2 x Mitsubishi A6M2 |

| Georgia Louise Harris Brown |

| Julian Abele |

| Norma Merrick Sklarek |

| William Sidney Pittman |