Philippine–American War facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Philippine American WarDigmaang Pilipino–Amerikano |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of Decolonisation of Asia | |||||||||

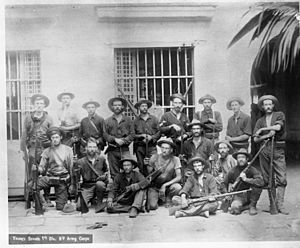

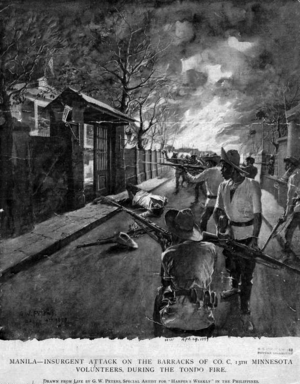

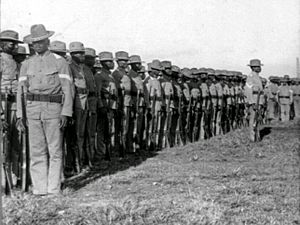

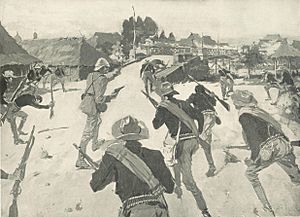

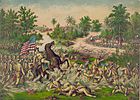

Clockwise from top left: U.S. troops in Manila, Gregorio del Pilar and his troops around 1898, Americans guarding the Pasig River bridge in 1898, the Battle of Santa Cruz (1899) |

|||||||||

|

|||||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||||

|

1899–1902:

|

1899–1902:

|

||||||||

|

1902–1913:

|

1902–1906: 1899–1905: 1899–1913: |

||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||||

|

|

||||||||

| Units involved | |||||||||

|

1899–1902:

1902–1913:

|

1899–1902:

1902–1913 |

||||||||

| Strength | |||||||||

|

≈80,000–100,000 regular and irregular |

||||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||||

| 4,200 killed, 2,818 wounded, several succumbed to disease | About 10,000 killed (Emilio Aguinaldo estimate), 16,000–20,000 killed (American estimate) |

||||||||

| Filipino civilians: 200,000–250,000 died | |||||||||

The Philippine–American War was a fight between the First Philippine Republic (Filipinos) and the United States. It lasted from February 4, 1899, to July 2, 1902. This war started because the United States took control of the Philippines after the Spanish–American War. The U.S. did not recognize the Philippines' declaration of independence.

Fighting began on February 4, 1899, in what is known as the 1899 Battle of Manila. On June 2, 1899, the First Philippine Republic officially declared war on the United States. The Filipino President, Emilio Aguinaldo, was captured on March 23, 1901. The American government officially ended the war on July 2, 1902, declaring victory.

However, some Filipino groups kept fighting for several more years. These included veterans of the Katipunan, a Filipino revolutionary group. One leader was Macario Sakay, who started the Tagalog Republic in 1902. Other groups, like the Moro people in the south, also continued to resist. This resistance, called the Moro Rebellion by the Americans, ended on June 15, 1913, after the Battle of Bud Bagsak.

The war caused many deaths, especially among Filipino civilians. At least 200,000 Filipino civilians died, mostly from diseases like cholera and from hunger. The war and American rule changed the islands' culture. Protestantism grew, and the Catholic Church lost some power. English became the main language for government, schools, and business.

In 1902, the United States Congress passed the Philippine Organic Act. This law set up the Philippine Assembly, where Filipino men could elect members. This act was later replaced by the 1916 Jones Act. This law was the first time the U.S. government officially promised to give the Philippines independence. The 1934 Tydings–McDuffie Act created the Commonwealth of the Philippines the next year. This gave Filipinos more self-rule. The U.S. finally granted full independence to the Philippines in 1946 through the Treaty of Manila.

Contents

Why the War Started

The Philippine Revolution Against Spain

The Philippine–American War was a continuation of the fight for independence that began in 1896. This was the Philippine Revolution against Spanish rule. Andrés Bonifacio started the Katipunan on July 7, 1892. This was a secret group that wanted to gain independence from Spain through armed revolt.

In August 1896, the Spanish found out about the Katipunan, and the revolution began. Filipino fighters in Cavite province won early battles. Emilio Aguinaldo, a mayor from Cavite, became a very popular leader. He took control of much of eastern Cavite. Aguinaldo and his group eventually led the revolution. He was elected president of a new government on March 22, 1897.

Aguinaldo's Exile and Return

By late 1897, the Spanish had taken back most of the land the rebels had captured. Aguinaldo and the Spanish Governor-General, Fernando Primo de Rivera, started talking about peace. Aguinaldo was hiding in Biak-na-Bato in Bulacan province.

On December 14, 1897, they made a deal called the Pact of Biak-na-Bato. Spain agreed to pay Aguinaldo $800,000 if he would leave the Philippines. Aguinaldo and 25 of his closest friends went to Hong Kong. Before leaving, Aguinaldo told other rebels to stop fighting. He said those who kept fighting were bandits. Aguinaldo later said Spain never paid the rest of the money.

While in Hong Kong, Aguinaldo met with U.S. Consul E. Spencer Pratt in Singapore on April 22, 1898. Aguinaldo said Pratt promised that the U.S. would recognize Philippine independence. Pratt said this promise came from Commodore George Dewey, a U.S. Navy commander. With these promises, Aguinaldo agreed to return to the Philippines.

However, Pratt later said he made no political deals with Aguinaldo. Admiral Dewey also said he promised nothing about the future of the Philippines. He wanted to avoid any formal alliance with the Filipino rebels.

Filipino historian Teodoro Agoncillo believed the Americans broke their word. He said the U.S. first asked Aguinaldo for help against Spain. He felt Dewey secretly planned for Spain to surrender only to the Americans. Agoncillo concluded that the Americans came to the Philippines "not as a friend, but as an enemy masking as a friend."

Aguinaldo returned to the Philippines on May 19, 1898. This was just after Commodore Dewey's forces destroyed the Spanish fleet in the Battle of Manila Bay. In less than three months, the Philippine Revolutionary Army had taken almost all of the Philippines. Only Manila remained under Spanish control. Aguinaldo declared independence at his home on June 12, 1898.

Neither the United States nor Spain recognized this declaration. On December 10, 1898, the U.S. and Spain signed the Treaty of Paris. This treaty officially ended the Spanish–American War. In the treaty, Spain gave the Philippines to the United States for $20 million.

After returning, Aguinaldo first set up a "Dictatorial Government." Then he created a "Revolutionary Government" and became "President." He organized a congress in Malolos, Bulacan, to write a constitution. This led to the official start of the "Philippine Republic" in January 1899. This government is now known as the First Philippine Republic. Aguinaldo is considered the first President of the Republic of the Philippines.

The Start of the Conflict

The Battle for Manila (1898)

On July 9, 1898, U.S. General Anderson reported that Aguinaldo was trying to take Manila without American help. He worried this would make it hard for the U.S. to set up its own government. On July 15, Aguinaldo declared himself the civil leader of the Philippines.

General Anderson also wrote that Aguinaldo had set up a military government. He said Aguinaldo was stopping supplies from reaching the Americans. Anderson told Aguinaldo that the Americans needed supplies and that Aguinaldo must help.

On July 24, Aguinaldo warned General Anderson not to land American troops in areas Filipinos had conquered. He said they must first agree on where the troops would go. General Merritt, another U.S. commander, decided not to talk directly with Aguinaldo. He believed his orders from the U.S. President meant he had full authority.

U.S. commanders thought Aguinaldo's forces were telling the Spanish about American plans. A U.S. Army Major later confirmed this after studying Filipino documents.

The U.S. and Spanish leaders had a secret agreement. Spanish forces would surrender only to the Americans, not to the Filipinos. To save face, they would have a fake battle in Manila. The Spanish would lose, and Filipinos would not be allowed into the city. Before the battle, General Anderson told Aguinaldo not to let his troops enter Manila. He warned that they would be fired upon if they crossed into the city.

On August 13, American forces captured Manila from the Spanish. Before this, Americans and Filipinos were allies against Spain. After Manila was captured, Spain and the U.S. worked together, leaving out the Filipinos. Filipino fighters were angry they were not allowed to enter their own capital. Relations got worse as Filipinos realized the Americans planned to stay.

End of the Spanish–American War

On August 12, 1898, a peace agreement was signed between the U.S. and Spain. This agreement stopped the fighting. It stated that the United States would control Manila until a peace treaty decided the future of the Philippines.

The Filipino Revolutionary Government held elections between June and September 1898. This led to the creation of the Malolos Congress. This group wrote the Malolos Constitution, which was approved on January 21, 1899. This officially created the First Philippine Republic, with Emilio Aguinaldo as president.

The peace treaty talks began in Paris in October 1898. President McKinley first wanted only Luzon, Guam, and Puerto Rico. But American generals and European diplomats advised him to take all of the Philippines. They said it would be "cheaper and more humane" to take the whole country.

On October 28, 1898, McKinley decided to demand the entire Philippine archipelago. Spanish negotiators were angry but agreed when offered $20 million for their improvements to the islands. On December 10, 1898, the U.S. and Spain signed the Treaty of Paris. Spain officially gave the Philippine Islands to the United States for $20 million.

In the U.S., some people wanted the Philippines to be independent. They argued that the U.S. had no right to control a land where people wanted to rule themselves. Andrew Carnegie, a rich businessman, even offered to pay the U.S. government $20 million to give the Philippines independence. Others argued that if the U.S. didn't take the islands, another country like Empire of Japan would.

"Benevolent Assimilation"

On December 21, 1898, President William McKinley announced a policy called "benevolent assimilation." He said the U.S. would rule with "justice and right" for the "greatest good of the governed." He stated that the U.S. was taking over from Spain. He told the military commander, General Otis, to tell Filipinos that Americans came as "friends" to protect their homes, jobs, and rights.

The Spanish gave up Iloilo to the Filipinos on December 26. An American general, Marcus P. Miller, arrived in Iloilo on December 28. A Filipino official there refused to let Miller's forces land without orders from Aguinaldo.

Major General Elwell Stephen Otis, the new Military Governor of the Philippines, delayed publishing McKinley's announcement. On January 4, 1899, Otis published a changed version. He removed words like "sovereignty" and "protection" that were in the original. Otis said he believed the U.S. wanted to set up a free government for the Filipinos.

However, the U.S. War Department had also sent the original announcement to General Miller. Miller didn't know Otis had changed it, so he published the original version. This original version reached Aguinaldo. Aguinaldo was already upset that Otis had changed his own title to "Military Governor of the Philippines" instead of "in the Philippines."

Aguinaldo received the original announcement and saw the changes Otis had made. On January 5, he issued his own statement. He protested the U.S. taking over Filipino land. He said his government would fight if American troops tried to take the Visayan Islands. He accused the U.S. of being "oppressors of nations."

Aguinaldo later issued another statement, saying he would defend the Philippines' freedom and independence. Otis saw these statements as a declaration of war. He strengthened American positions and alerted his troops. Aguinaldo's statements made many Filipinos determined to fight. About 40,000 Filipinos left Manila in 15 days.

On January 6, Filipino official Felipe Agoncillo was in Washington. He asked to meet with the U.S. President to discuss the Philippines. The next day, U.S. officials were surprised to learn that messages telling General Otis to be gentle with the rebels had reached Agoncillo. Agoncillo then sent these messages to Aguinaldo.

On January 8, Agoncillo stated that Filipinos would never agree to be a U.S. colony. He said Filipino soldiers would not give up their weapons until Aguinaldo told them to. Filipino groups in London, Paris, and Madrid also sent messages to President McKinley. They protested American troops landing in Iloilo. They said the U.S. claim to control was too early because the peace treaty was not yet approved.

By January 10, Filipino rebels were ready to attack. They wanted the Americans to fire the first shot. A Filipino colonel named Cailles refused to move his troops back. He told an American interpreter that he would not deal with any American since McKinley opposed their independence. He said, "War, war, is what we want." Aguinaldo approved of Cailles' actions. He believed the Americans were just waiting for more troops.

On January 31, 1899, the Filipino Minister of Interior ordered that all empty lands be planted. This was to provide food for the people, as war with the Americans seemed certain.

The War Begins

Outbreak of Fighting

On the evening of February 4, 1899, Private William W. Grayson, an American soldier, fired the first shots of the war. He was a guard for the 1st Nebraska Infantry Regiment. He told four Filipino soldiers to "Halt!" When they moved their rifles, he fired at them.

Later that day, Aguinaldo declared that peace with the Americans was broken. He said they should be treated as enemies. This started the 1899 Battle of Manila. The next day, Filipino General Isidoro Torres brought a message from Aguinaldo to General Otis. Aguinaldo said the fighting started by accident and wanted it to stop. He asked for a neutral zone between the two sides. Otis refused, saying the "fighting, having begun, must go on."

On February 5, General Arthur MacArthur ordered his troops to advance. This began a full-scale armed conflict. The first Filipino soldier to die was Corporal Anastacio Felix. On June 2, 1899, the First Philippine Republic officially declared war on the United States.

American War Strategy

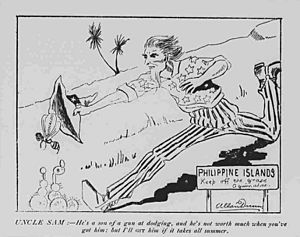

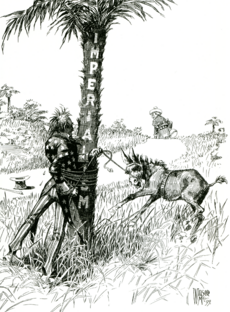

The U.S. government and media said that taking over the Philippines was to free and protect the people. Senator Albert J. Beveridge said Americans went to war to free Cubans, Puerto Ricans, and Filipinos. He claimed they stayed in the Philippines to protect Filipinos from other European countries. He also said they wanted to teach Filipinos American-style democracy.

On February 11, 1899, American naval forces attacked the city of Iloilo. Filipino forces set the town on fire before leaving. American ground forces captured the city with no American deaths. However, the Filipino part of the city was almost completely destroyed.

After securing Manila, American forces moved north. They chased the Filipino forces and their commanders. In September 1899, the U.S. military changed its strategy. They focused on controlling key areas. They gathered civilians into "zones of protection" away from the guerrilla fighters. Many civilians in these camps died from disease due to poor conditions.

General Otis became known for some of his actions. He was told to avoid conflict, but he did little to stop the war from starting. Otis demanded that the Philippine Army surrender completely. He often made big military decisions without asking leaders in Washington. He thought Filipino resistance would end quickly. Even when this was proven wrong, he kept saying the rebellion was defeated. He claimed remaining fights were just from "isolated bands of outlaws."

Otis also tried to hide information about American military actions from the media. When letters describing American actions reached the news, Otis would send the news clippings to the soldier's commander. The commander would then make the soldier take back their statements.

Filipino War Strategy

The Filipino forces had between 80,000 and 100,000 fighters. Many also had tens of thousands of helpers. Most of them had only bolo knives, bows and arrows, and spears. These weapons were much weaker than the American guns.

The goal of the First Philippine Republic was to create a free, independent, and stable nation. This nation would be led by educated Filipinos, called ilustrados. Local leaders, landowners, and businessmen were also important. The war was strongest when these groups and the peasants worked together against the U.S.

The peasants, who were most of the fighters, had different goals than their educated leaders. It was hard to unite people from different social groups and different parts of the country. Aguinaldo and his generals needed to keep Filipinos united against the U.S. This was their main goal.

The Filipino military aim was not to defeat the U.S. Army. Instead, they wanted to cause constant losses for the Americans. In the early part of the war, the Philippine Army used regular military tactics. They hoped to cause enough American deaths to make President McKinley lose the 1900 presidential election. They hoped that William Jennings Bryan, who was against imperialism, would pull American forces out of the Philippines.

McKinley's victory in 1900 made the Filipino rebels feel discouraged. Many realized the U.S. would not leave soon. They also suffered many losses against American forces with better weapons and training. Aguinaldo then decided to change his approach. On November 13, 1899, Emilio Aguinaldo ordered that guerrilla warfare would be their new strategy.

Guerrilla War Phase

Using guerrilla warfare made it much harder for Americans to control the Philippines. In the first four months of this new fighting style, the Americans had almost 500 casualties. The Philippine Army started bloody ambushes and raids. They won battles at Paye, Catubig, Makahambus, Pulang Lupa, Balangiga, and Mabitac. At first, it seemed Filipinos might be able to fight the Americans to a standstill. President McKinley even thought about pulling out troops when the guerrilla attacks began.

Martial Law

On December 20, 1900, General Arthur MacArthur Jr. took over as U.S. Military Governor. He put the Philippines under martial law. He said that guerrilla actions would no longer be allowed. He explained the rules for how the U.S. Army would treat guerrillas and civilians. Guerrillas who wore no uniform but peasant clothes would be held responsible. Secret groups that collected taxes for the revolution would be treated as "war rebels." Filipino leaders who kept working for independence were sent away to Guam.

Decline of the First Philippine Republic

The Philippine Army kept losing battles to the better-armed United States Army. This forced Aguinaldo to keep moving his headquarters during the war.

On March 23, 1901, General Frederick Funston and his troops captured Aguinaldo in Palanan, Isabela. They had help from some Filipinos called the Macabebe Scouts. The Americans pretended to be prisoners of the Scouts, who wore Philippine Army uniforms. Once they entered Aguinaldo's camp, they quickly captured him.

On April 1, 1901, Aguinaldo swore an oath at the Malacañan Palace in Manila. He accepted the authority of the United States over the Philippines. On April 19, he told his followers to put down their weapons and stop fighting.

"Let the stream of blood cease to flow," Aguinaldo said. "The lesson which the war holds out... leads me to the firm conviction that the complete termination of hostilities and a lasting peace are... essential for the well-being of the Philippines."

Aguinaldo's capture was a big blow to the Filipino cause. But it was not as big as the Americans had hoped. General Miguel Malvar took over leadership of the Filipino government. He had been fighting defensively, but now he launched attacks against American-held towns in the Batangas region. General Vicente Lukbán in Samar and other officers continued the war in their areas.

General Bell chased Malvar and his men without stopping. This forced many Filipino soldiers to surrender. Finally, Malvar surrendered on April 16, 1902, along with his sick wife and children. By the end of that month, almost 3,000 of Malvar's men had also surrendered. With Malvar's surrender, the Filipino war effort weakened even more.

Setting Up a Civilian Government

On March 3, 1901, the U.S. Congress passed a law that allowed the president to set up a civilian government in the Philippines. Before this, the president had ruled the Philippines using his war powers. On July 1, 1901, a civilian government officially began. William H. Taft became the civil governor. Later, in 1903, his title was changed to Governor-General.

A public school system was started in 1901. English was used for teaching. This caused a shortage of teachers. So, the Philippine Commission brought 600 teachers from the U.S. These teachers were called Thomasites. They taught free primary education to prepare people for citizenship. Also, the Catholic Church was no longer the official church. A lot of church land was bought and given out to people.

A law against rebellion was made in 1901. Another law against banditry followed in 1902.

Official End of the War

The Philippine Organic Act was approved on July 1, 1902. This law confirmed the earlier order that created the Second Philippine Commission. The act also said that a two-house legislature would be created. There would be a lower house, the Philippine Assembly, elected by the people. The upper house would be the appointed Philippine Commission. The act also gave Filipinos the same rights as Americans, like those in the United States Bill of Rights.

On July 2, the U.S. Secretary of War announced that the rebellion had ended. He said that civilian governments were set up across the Philippines. So, the office of military governor was ended. On July 4, Theodore Roosevelt, who became U.S. President after McKinley's death, announced a full pardon for everyone who fought in the conflict.

On April 9, 2002, Philippine President Gloria Macapagal Arroyo declared that the Philippine–American War ended on April 16, 1902. This was when General Miguel Malvar surrendered. She made the 100th anniversary of that date a national holiday.

The Kiram-Bates Treaty helped the U.S. control the Sultanate of Sulu. American forces also took control of mountain areas that had resisted Spanish rule.

Casualties of the War

Many more Filipinos died than Americans during the war. The United States Department of State says that over 4,200 American soldiers died. Over 20,000 Filipino soldiers also died. It is believed that as many as 200,000 Filipino civilians died from violence, hunger, and disease. Most of these deaths were from famine and disease. A cholera outbreak at the end of the war killed between 150,000 and 200,000 people.

What Happened After the War

Conflicts After 1902

After military rule ended on July 4, 1902, the Philippine Constabulary was created. This was a police force for the whole country. Its job was to stop banditry and deal with the remaining rebel groups. This police force slowly took over from the U.S. Army in fighting hostile groups.

Some parts of Aguinaldo's Republic and other rebel groups kept fighting. The American government called these groups "bandits" or "fanatics." They were not seen as a military threat but as a law enforcement problem.

In 1902, Macario Sakay started the Republika ng Katagalugan. He claimed it was the true successor to the First Philippine Republic. This republic ended in 1906 when Sakay and his followers surrendered. They were offered a pardon but were arrested and executed the next year.

After 1903, organized groups of bandits became a problem in some provinces. One group was the Pulahan (meaning "red" in Filipino). They were from the mountains of Samar and Leyte. They wore red clothes and believed special charms would make them bulletproof. The last of these groups surrendered by 1911.

The American government had signed a treaty with the Sultanate of Sulu at the start of the war. This treaty was supposed to prevent fighting in the southern Philippines. But after the Filipino resistance in the north ended, the U.S. canceled the treaty. They began to take control of Moro land. This led to the Moro Rebellion.

The Moro Rebellion began with the Battle of Bayan in May 1902. In the First Battle of Bud Dajo in March 1906, U.S. forces killed 800-900 Moros. The rebellion continued until the Battle of Bud Bagsak in June 1913. In this battle, Moro forces were defeated by U.S. troops led by General John J. Pershing. This battle marked the end of the Moro conflict.

A 1907 law made it illegal to display flags or symbols used during the "late insurrection." Some historians believe these later conflicts are part of the war.

Cultural Changes

The power of the Roman Catholic Church was reduced. The U.S. government separated the Church from the state. It also bought and redistributed a large amount of Church land. This was one of the first attempts at land reform in the Philippines. The U.S. bought about 170,917 hectares of land for over $7 million. The land was then offered for sale or lease to farmers who did not own land.

In 1901, at least 500 teachers came from the U.S. on the ship U.S. Army Transport Thomas. These teachers were called Thomasites. They helped establish education as a major American contribution to the Philippines. They taught in many areas, including the Bicol Region, where there was strong resistance to American rule. Twenty-seven of the original Thomasites died from tropical diseases or were killed by Filipino rebels. Despite the difficulties, the Thomasites kept teaching. They built schools that prepared students for jobs and careers. By the end of 1904, most primary classes were taught by Filipinos under American supervision.

Many American military leaders who served in the Philippine-American War later became important. For example, Douglas MacArthur, Chester W. Nimitz, and Walter Krueger were senior commanders in the U.S. campaign to free the Philippines from Japan during World War II.

Philippine Independence (1946)

On January 20, 1899, President McKinley appointed the First Philippine Commission. This group, led by Jacob Gould Schurman, studied conditions in the islands. In their report, they said Filipinos wanted independence but were not ready for it. They suggested setting up a civilian government quickly. This would include a two-house legislature, local governments, and a new system of free public elementary schools.

From the start, U.S. leaders said their goal was to prepare the Philippines for independence. The question was not if the Philippines would get self-rule, but when. So, political development in the islands happened quickly. The Philippine Organic Act of July 1902 stated that a legislature would be created. It would have an elected lower house, the Philippine Assembly, and an upper house appointed by the U.S. president.

The Jones Act, passed by the U.S. Congress in 1916, promised eventual independence. It also created an elected Philippine senate. The Tydings–McDuffie Act (Philippine Independence Act), approved on March 24, 1934, set up self-government for the Philippines. It also planned for full independence after ten years. However, World War II and the Japanese occupation of the Philippines delayed this. In 1946, the Treaty of Manila officially recognized the independence of the Republic of the Philippines. The U.S. gave up its control over the islands.

|

See also

In Spanish: Guerra filipino-estadounidense para niños

In Spanish: Guerra filipino-estadounidense para niños

- Campaigns of the Philippine–American War

- History of the Philippines (1898–1946)

- Philippines–United States relations

- Timeline of the Philippine–American War