Pistolerismo facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Pistolerismo |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Part of Spanish liberal state crisis | |||

| Date | 1917-1923 | ||

| Location |

Spain, mainly in industrial areas and especially in Barcelona

|

||

| Goals | Achievement of social rights for the working class (CNT and UGT) Repression of all union trade initiatives (counter-revolutionary front) | ||

| Methods | Murders, bombing attacks, strike repressions | ||

| Resulted in | Dictatorship of Primo de Rivera | ||

| Parties to the civil conflict | |||

|

|||

| Lead figures | |||

|

|

|||

Pistolerismo was a tough time in Spanish history between 1917 and 1923. It was a period when bosses and workers fought violently. This happened mostly in industrial cities like Barcelona.

During this time, factory owners sometimes hired people to attack or even kill trade unionists (workers' leaders). Workers' groups also fought back. Many armed groups appeared, made up of "pistoleros," or gunmen.

The worst violence happened in Catalonia, especially in Barcelona. Hundreds of people were killed or hurt because of these fights. These clashes played a big part in the end of Spain's old government system, which was called the Liberal State. It finally ended with a coup by Primo de Rivera in 1923.

Contents

Spain's Past: A Quick Look

At the start of the 1900s, Spain was a parliamentary monarchy. This means it had a king but also a parliament. This system began in 1874 after the First Spanish Republic ended.

The political system worked by having two main parties, the Liberal and Conservative parties, take turns running the country. The government was often decided even before elections happened.

The Spanish government at that time relied on three main things: the king, the Catholic Church, and the army. After King Alfonso XII died in 1885, his son Alfonso XIII became king. He ruled until 1931.

The Church had a lot of power in Spain. It ran schools, hospitals, and nursing homes. The Church also had strong anti-liberal ideas.

The army was also very powerful. It often stepped in to control politics. The government couldn't fully control the army. The army saw itself as protecting social order. Political parties often used the army to stop strikes and protests. This made violence seem like a normal way to solve problems.

Why the Conflict Started

Pistolerismo grew out of problems with Spain's government system. This system was weak and couldn't handle the big changes happening in society. This weakness led to a lot of social unrest and violence.

Factories and Workers Unite

In the late 1800s, Spain started to build more factories. This happened mostly in Catalonia. Many people moved from farms to cities like Barcelona to find factory jobs.

This led to big changes. Many workers in one place helped socialist and anarchist ideas spread. Workers started forming groups. Strikes and protests grew bigger and more frequent. In 1888, the first national trade union, the Unión General de Trabajadores (UGT), was formed. This helped workers organize their demands.

The government worried about these strikes. They tried to stop them by using more police, like the Civil Guard. But police forces weren't enough. Protests were happening all over the country.

So, the government often used the army. This made public order a military issue. When the government couldn't stop protests in faraway places, people started to defend themselves. Landlords and factory owners began using violence to fight strikes and protect their property. For example, the Requeté, a group linked to Carlists, fought against left-wing groups. This made violence even more common.

Losing Colonies

Another big problem was Spain's defeat in the Spanish–American War in 1898. Spain lost its last colonies in the Caribbean Sea and Pacific Ocean. Cuba and Philippines became independent. The U.S.A. took Puerto Rico and Guam.

This defeat had a huge impact at home. Many people criticized politicians. There was a strong feeling that Spain needed to improve. Some people thought political attacks were the answer, while others wanted the army to take control. After the war, many soldiers returned to Spain. The government then used this larger army to brutally stop protests and strikes. This made people trust the government less, as it relied so much on the army.

World War I's Impact

When First World War started in 1914, Spain stayed neutral. This helped Spanish factories grow a lot. They made raw materials and military gear for the countries fighting the war. Thousands of workers moved to industrial areas.

However, this also caused problems. With so many people looking for jobs, bosses could pay lower wages. This made workers' lives harder. Prices for basic goods also went up. All these issues led to more protests about food and wages. This forced the government to change. The difficult situation for workers, especially where left-wing ideas were strong, made workers' groups grow and become more extreme. The war made all existing problems much worse in Spain.

The Start of the Conflict

In 1916, the government tried to fix the economy by cutting military spending. But this failed, and the economy got worse. The government fell.

In June 1917, soldiers protested by forming their own unions. In July, a group of rich Catalans, the Lliga Regionalista, created a regional assembly. They wanted to change the constitution, going against the parliament in Madrid. In August, the first general strike in Spanish history happened. It was organized by UGT, with help from the Confederación Nacional del Trabajo (CNT), a group of anarchist unions.

The strike stopped some big Spanish cities for a few days. But the police and army crushed it. This brutal response made some extreme members of the CNT decide to use violence.

Before this, the CNT, led by Salvador Seguí and other moderate members, mostly used long strikes to get what they wanted. But after the general strike was crushed, some anarchists formed armed groups. They started attacking bosses and factory owners. Many attacks happened in Barcelona between 1917 and 1918. The first anarchist groups were quickly stopped by police. But as the war ended, the situation got worse, and violence continued with spontaneous groups of workers.

The "Bolshevik Three Years"

After World War I, the economy got worse. Prices went up, and exports went down. This led to a lack of goods and many job losses. The time between the end of the war and 1921 is called the Trienio Bolscevico (Bolshevik Three Years). This is because strikes and worker struggles reached their highest point. The October Revolution in Russia strongly influenced Spain. It made socialist and anarchist ideas more popular and encouraged left-wing unions to fight harder.

In 1918, the two main unions, CNT and UGT, joined forces in some areas to make strikes more effective. A key event was the Canadenca strike in February 1919. This strike stopped a factory for 44 days. It forced the Spanish government to create a law for an eight-hour working day.

The CNT grew very fast, from about 80,000 members in 1918 to over 845,000 in 1919. It became the most important union in Spain. The harsh response to the Canadenca strike also led the extreme part of the CNT to take control. Salvador Seguí's moderate approach was replaced by targeted killings. Soon, anarchist groups formed, using violence and murders as political tools.

Meanwhile, conservative groups and bosses worried. To stop the CNT, they formed their own armed groups. So, from early 1919, violence increased rapidly. Spanish governments even tried to make strikes more violent by sending people to stir up trouble within worker groups. This gave them an excuse for brutal crackdowns. But this plan failed and only made the fighting worse.

Because the police were weak and the government couldn't keep order, more private groups started using weapons to protect their interests. People began to see their political opponents as enemies who needed to be defeated by any means, including killing. This led to terrible clashes. Hundreds of people were killed or hurt. The government's authority also weakened.

Barcelona's Special Situation

Political violence was widespread in Spain after WWI, but Barcelona was the worst place. It was Spain's main industrial city. Socialist and anarchist ideas were very popular among workers there. During the war, thousands of workers moved to Barcelona for factory jobs. By 1919, half of the CNT's members were in Barcelona or nearby. The city also had the most strikes in Spain.

This situation made conservative groups and bosses in Barcelona support and pay for private armed groups. They wanted to stop the anarcho-syndicalist movement. But this only made anarchist groups fight back harder. Between 1919 and 1920, they increased personal attacks and bombings. Violence became a normal part of these social clashes.

A group formed to fight against unions and anarchists. It included local politicians, armed groups, and business leaders. The Federación Patronal de Barcelona, a group of rich business owners, heavily funded these private armed groups.

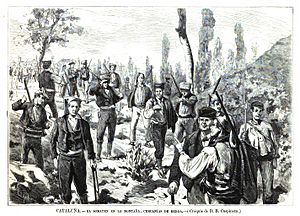

The Somatén

The biggest armed group was Somatén armado de Catalunya. It was an old group from the Middle Ages, meant to protect Catalan citizens. Its members were private citizens who could carry weapons. In the late 1800s, it was reformed to work with the army. It became legal to use violence to keep social peace. By 1909, Somatén had 44,000 members. It helped control the population and limit socialist and anarchist ideas. In 1905, a royal order made it an official police force. It was then used to help stop strikes.

Somatén showed its strength during the Tragic Week of 1909. It took control of some cities, allowing the army to focus on Barcelona. Even though it was spread across Catalonia, Somatén didn't have a section in central Barcelona until 1919. But then, rich Catalans, who funded the group, decided to create a city center section to fight the union movement.

From then on, Somatén was often used by bosses to fight the CNT and anarchist groups. Its members took part in clashes and arrested many CNT activists. In March 1919, after a general strike, the government suspended constitutional rights and declared a state of war. Somatén was used to arrest many CNT members, who stayed in prison for a long time. Somatén was a key armed group for Barcelona's factory owners and helped increase violence in the city.

The Black Band

Around the same time, the Federación Patronal de Barcelona created a private police force called Banda Negra (Black Band). They wanted to increase military pressure against the unions. Manuel Bravo Portillo organized and led the Black Band. It quickly became important in stopping the CNT, thanks to money from factory owners. It was made up of criminals, former police, and union members. They attacked CNT leaders. In September 1919, anarchists killed Portillo. Rudolf Stalmann, known as König baron, became the new leader. König had a deal with Miguel Arleguì, Barcelona's police chief. This made the Black Band a sort of parallel police force. They started taking part in raids and questioning, using more and more violence against left-wing people. For some months, the group was protected by Jaime Milans del Bosch, the top military leader in Catalonia.

Violence was the main tool of the Black Band. It operated in Barcelona until mid-1920, when the government decided to break it up. The Black Band showed that Barcelona's industrial leaders didn't want to find a compromise with unions. This led to more violence in the city. Workers realized that to survive, they had to respond to violence with even more violence.

The winter of 1919-1920 was a turning point. Bosses closed factories for ten weeks to stop strikes. This made many workers' economic situations worse, leading to new strikes. From the start of the new year, conservative groups and government officials decided to crush the CNT using all possible methods. Two new military groups appeared in Barcelona, starting the bloodiest period in recent Spanish history. In 1920-1921, 148 people were killed and 365 injured in Barcelona alone due to these social fights.

The Sindicatos Libres

The main reason for the rise in killings was the brutal fight between CNT members and a new group called Sindicatos Libres. They were officially started on December 19, 1919, by Catholic workers linked to the Carlist movement. They tried to create a union that would support factory owners and defend the interests of Barcelona's rich families against left-wing unions. At first, the Libres group grew with help from the Carlist Party and support from important Catalan factory owners, journalists, and lawyers.

However, Sindicatos Libres grew even more when many workers joined them. From summer 1920, more workers rejected the CNT's anarchist ideas. They joined Libres because of their Catholic and conservative beliefs, or because they disagreed with the CNT's extreme methods. In autumn 1920, a real war began between the CNT and Libres. It started with an attempt to kill CNT leader Salvador Seguí. In just a few months, factories became battlegrounds, and murder attempts happened daily. Libres formed their own armed groups, made of Carlist workers and professional gunmen. These gunmen had been part of other armed groups like the Requeté. They had police support. From early 1921, they started breaking up CNT local groups, killing or arresting many anarchist members.

The Libres group went through three phases. First, until early 1921, they grew slowly because the CNT was still very strong. During this time, they got important help from Catalan owners and rich families. Second, from mid-1921 to October 1922, Libres became a huge movement, with 175,000 members in 1922. They were almost the only organized workers' group in Catalonia because the CNT was banned, and many left-wing activists were in prison or killed. In this period, they organized successful strikes and negotiations, getting good benefits for many workers. But their relationship with bosses got worse, and the group became more focused on workers' issues. Third, from late 1922 until Primo de Rivera's coup in September 1923, Libres lost official protection. The last Liberal governments tried to stop them. At the same time, the CNT started to reorganize, which weakened Libres even more. After a failed strike in August 1923, Libres began to shrink, and many workers left the group.

The Army and Ley de Fugas

The rise of Sindicatos Libres was strongly supported by official protection, especially after Severiano Martínez Anido arrived in Barcelona. In December 1920, the government decided to use the army heavily to defeat the anarcho-syndicalist groups in Catalonia. To do this, Anido was made both the civil and military governor of Barcelona, giving him huge power. Anido had close ties with Libres and helped them a lot with protection and military equipment.

Anido's appointment meant that military leaders were now more powerful than civil leaders in keeping public order. Civil authorities lost almost all their power. For nearly two years, Anido created his own military dictatorship within Liberal Spain. During this time, violence reached its highest point. To defeat the CNT and anarchist groups, the anti-union side used brutal methods. These included sending people away, stealing, searching people on the streets, arresting people without reason, and closing union offices and newspapers.

The most terrible method used was the Ley de Fugas (Law for the Fugitives). This was a way for security forces to kill union members without a trial. It started after the general strike of March 1919, but it became common after Anido arrived in Barcelona. Prisoners were told they were free, but as soon as they left prison, they were killed in cold blood. This system made it look like the killings happened because prisoners tried to escape. This way, no one was held legally responsible. It also made it almost impossible to tell who was a murderer and who was just a striker.

Overall, Anido's brutal actions, supported by different armed groups, greatly reduced the CNT's ability to defend workers' rights and organize strikes. In 1919, 3,250,000 working days were lost due to strikes. By 1921, this number dropped to 101,950. However, the anarcho-syndicalist movement was not completely defeated. From late 1922, it started to reorganize itself.

Towards the Dictatorship

During 1922, violence decreased a lot, not just in Barcelona but all over Spain. This was because the new government, from March 1922, tried to bring back law and order. The prime minister, Sanchez Guerra, restored constitutional rights. He also tried different ways to solve social conflicts, which had become terrible in both industrial and rural areas. One important decision was to remove Martinez Anido in October 1922. His brutal methods had made many people unhappy, even some rich families.

In the winter of 1922-1923, personal attacks and murders dropped significantly, especially in Barcelona. This was due to less social repression and the end of Anido's power. However, restoring constitutional rights allowed all left-wing activists who were illegally imprisoned to be freed. Because of this, CNT leaders started rebuilding their union, and the anarcho-syndicalist movement quickly regained strength. Anarchist action groups reappeared, wanting revenge against their enemies, especially Sindicatos Libres.

As a result, from February 1923, violence and personal attacks returned. These attacks were mainly aimed at leaders of Libres and the CNT. The situation got much worse after Salvador Seguí was murdered in March 1923. This stopped all efforts to stabilize Barcelona. This led to the last wave of violence, ending with a general strike by the CNT in August 1923. During this strike, 22 people died and 32 were injured.

Finally, this new wave of social clashes made Barcelona's industrial leaders lose all trust in the government in Madrid. Rich families and bosses saw the army as the only solution to the chaos. Also, Sindicatos Libres were losing the power they had gained. Meanwhile, different plans for a coup were being made by political and social groups who believed the political system needed to change from the top.

This situation helped Miguel Primo de Rivera, the new top military leader in Catalonia, rise to power. In summer 1923, he sent troops into the streets to militarize public spaces again. De Rivera made a deal with four generals in Madrid who were planning a coup. On September 11, 1923, he carried out his plan. During the celebration of the Catalan Nation, there were protests against the government and the army fighting in Morocco. De Rivera used this situation to take power. With help from Somatén leaders and support from industrial leaders, he took control from civil authorities in Catalonia. This forced the king to choose a side. King Alfonso XIII decided to support the coup. On September 15, he appointed de Rivera as the new prime minister.

What Happened Next

Overall, the period between 1917 and 1923 was a major turning point in Spanish history. During a time of big political, economic, and social changes, these years created deep divisions in Spanish society. These problems weren't solved later. They led to a long period of social clashes, political repression, and less personal freedom. This all ended in 1936 with a terrible civil war. Political and social violence played a key role in the crisis of Spain's Liberal State, pushing many parts of society to choose military solutions.

The violence of this period also affected future union struggles, especially during the Second Spanish Republic. The extreme nature of worker conflicts prevented moderate alternatives to the CNT from forming. This allowed the CNT to easily rebuild its leadership after Primo de Rivera's dictatorship ended in 1930. Also, the brutal repression by the anti-union side eliminated many moderate CNT members. This weakened Salvador Seguí's strategy and helped the extreme part of the organization. As a result, from the early 1930s, anarchist action groups reappeared, using social attacks and personal murders again. However, the level of violence seen between 1917 and 1923 was never reached again.

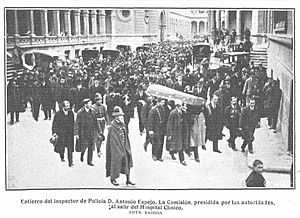

In conclusion, political violence grew from the weakness of the Spanish Liberal State. It greatly sped up its crisis, which was already deep by 1917. Both sides used violence without limits. By the end of the conflict, in Barcelona alone, 267 people were killed and 583 injured. Many important people died, including labor leaders like Pau Sabater, Evelio Boal, Salvador Seguí, and the lawyer Francesc Layret. On the other side, anarchists killed important politicians like Eduardo Dato, who was prime minister when he was killed in 1921.

See also

In Spanish: Pistolerismo para niños

In Spanish: Pistolerismo para niños

- Monarchy of Spain

- Spain geography

- Pope

- Economic history of Spain

- Origins of the labor movement in Spain

- Carlist wars

- Russian Revolution

- Bolshevik Party

- Spanish Cortes

- History of Anarchism

- History of Socialism

- Spanish Empire

- Catalan Nationalist Party

- Rif War

- Catholicism in the Second Spanish Republic

- Spanish Civil war

- Francisco Franco

- Politics of Spain