Ptolemy VIII Physcon facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Ptolemy VIII Euergetes II |

|

|---|---|

|

|

| King of the Ptolemaic Kingdom | |

| Reign | 170–164 BC with Ptolemy VI and Cleopatra II 145–132/1 BC with Cleopatra II and Cleopatra III 127/6–116 BC with Cleopatra III and (from 124 BC) with Cleopatra II (Ptolemaic) |

| Predecessor | Ptolemy VI and Cleopatra II |

| Successor | Ptolemy IX and Cleopatra II and Cleopatra III |

| Consorts | Cleopatra II of Egypt (m. 145 BC) Cleopatra III of Egypt (m. 142 or 141 BC) |

| Children |

|

| Father | Ptolemy V of Egypt |

| Mother | Cleopatra I of Egypt |

| Born | c. 184 BC |

| Died | 28 June 116 BC (aged around 68) |

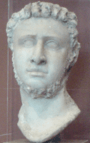

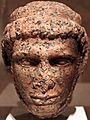

Ptolemy VIII Euergetes II Tryphon (born around 184 BC – died June 28, 116 BC) was a king of ancient Egypt. He belonged to the Ptolemaic dynasty, a family of Greek rulers. People sometimes called him Physcon, which meant "Fatty." He was the younger son of King Ptolemy V and Queen Cleopatra I. His time as king was full of big fights and disagreements with his older brother, Ptolemy VI, and his sister, Cleopatra II.

Ptolemy VIII became a co-ruler with his siblings in 170 BC, just before a major war. During this war, his brother Ptolemy VI was captured. Ptolemy VIII then became the sole king for a short time. After the war ended in 168 BC, his brother returned, and their arguments continued. In 164 BC, Ptolemy VIII took over as the only king, but he was forced out in 163 BC. The Romans stepped in and gave him control of Cyrene. From there, he often tried to take Cyprus from his brother, as the Romans had promised it to him.

After Ptolemy VI died in 145 BC, Ptolemy VIII came back to Egypt. He became co-ruler and married his sister, Cleopatra II. However, he was very strict with those who opposed him. He also decided to marry his niece, Cleopatra III, and made her a co-ruler too. This led to a civil war from 132/1 to 127/6 BC. During this war, Cleopatra II controlled the city of Alexandria. She had the support of the Greek people in Egypt. Ptolemy VIII and Cleopatra III controlled most of the rest of Egypt. They were supported by the native Egyptian people. For the first time, native Egyptians were given important jobs in the government. Ptolemy VIII won the war. He ruled with both Cleopatra II and Cleopatra III until he died in 116 BC.

Ancient Greek writers were very critical of Ptolemy VIII. They said he was cruel and made fun of him for being fat. They often compared him negatively to his brother, Ptolemy VI, whom they praised. Historian Günther Hölbl called him "one of the most brutal and at the same time one of the shrewdest politicians of the Hellenistic Age."

Contents

Early Life and Family Background

Ptolemy VIII was the younger son of Ptolemy V, who ruled Egypt from 204 to 180 BC. His father's reign was largely shaped by the Fifth Syrian War. In this war, Egypt fought against the Seleucid king Antiochus III. Antiochus III defeated Egypt and took over some of its lands.

To make peace, Ptolemy V married Antiochus III's daughter, Cleopatra I, in 194 BC. Their oldest son, Ptolemy VI, was born in 186 BC and was the heir to the throne. They also had a daughter, Cleopatra II. Ptolemy VIII, their youngest child, was likely born around 184 BC.

The defeat in the war caused problems for Ptolemy V's rule. Some people at court wanted to fight again to make Egypt strong. Others wanted to avoid the costs of rebuilding the army. When Ptolemy V died suddenly in 180 BC, his son Ptolemy VI became king. He was only six years old. Power then went to his guardians. These guardians preferred peace. Because of this, some people who wanted war started to look to the young Ptolemy VIII as their leader.

First Time as King (170–163 BC)

Becoming King and the Sixth Syrian War

In 175 BC, the Seleucid king, who had been peaceful, was murdered. His brother, Antiochus IV, took the throne. This unstable situation made the war-supporters in Egypt stronger. By 172 BC, Ptolemy VI's guardians seemed to agree with them.

In October 170 BC, Ptolemy VIII, who was about sixteen, became a co-ruler. He joined his brother and sister, who were already married to each other. This year was declared the start of a new era. Historians believe these ceremonies were meant to unite the different groups at court before the war. Ptolemy VI remained the main king. His coming-of-age ceremony was held, officially ending the guardians' rule. But in reality, the guardians still ran the government.

The Sixth Syrian War began soon after, likely in early 169 BC. Ptolemy VIII probably stayed in Alexandria. The Egyptian army marched to invade Palestine but was defeated by Antiochus IV. The army retreated, and Antiochus took a border fort. He then moved towards the Nile Delta.

Because of this defeat, the guardians were removed from power. Two generals took their place. As Antiochus IV moved towards Alexandria, Ptolemy VI went to meet him. They made a peace deal, which made Egypt a weaker state under Seleucid control. When people in Alexandria heard about this, they rioted. The generals rejected the deal and Ptolemy VI's authority. They declared Ptolemy VIII the only king. Cleopatra II's position stayed the same. Antiochus IV then surrounded Alexandria, but he could not capture the city. He left Egypt in September 169 BC, leaving Ptolemy VI as his puppet king in Memphis.

Within two months, Ptolemy VIII and Cleopatra II made up with Ptolemy VI. He returned to Alexandria as their co-ruler. The government then rejected the deal Ptolemy VI had made with Antiochus IV. They started to recruit new soldiers from Greece. In response, Antiochus IV invaded Egypt again in spring 168 BC. He quickly took Memphis and was crowned king of Egypt. He then moved towards Alexandria. However, the Ptolemies had asked Rome for help. A Roman group met Antiochus and forced him to agree to a settlement, ending the war.

At first, the shared rule of the two brothers and Cleopatra II continued. But Egypt's defeat in the war had greatly damaged the royal family's image. This caused a lasting split between Ptolemy VI and Ptolemy VIII.

In 165 BC, a court official named Dionysius tried to use the conflict between the brothers to gain power. He told the people of Alexandria that Ptolemy VI had tried to kill Ptolemy VIII. He tried to start a riot. Ptolemy VI convinced Ptolemy VIII that the claims were false. The two brothers appeared together in public, calming the situation. Dionysius fled and caused some soldiers to rebel. There was heavy fighting for the next year. This and another revolt were attempts to overthrow the Ptolemies. Ptolemy VI successfully stopped the rebellion.

Late in 164 BC, Ptolemy VIII, who was about twenty, somehow removed Ptolemy VI and Cleopatra II from power. Ptolemy VI fled to Rome and then to Cyprus. The exact details are not known. Ptolemy VIII then took the title Euergetēs, meaning 'benefactor'. This title was used by his ancestor Ptolemy III. It also helped to show he was different from Ptolemy VI and Cleopatra II. Ptolemy VIII was said to be a harsh ruler. His minister used torture to get rid of enemies. In summer 163 BC, the people of Alexandria rioted against Ptolemy VIII. They forced him out and called Ptolemy VI back to power.

Ruling Cyrenaica (163–145 BC)

When Ptolemy VI returned to power, Roman agents convinced him to give Ptolemy VIII control of Cyrenaica. Ptolemy VIII went to Cyrene, but he was not happy. In late 163 or early 162 BC, he went to Rome to ask for help. The Roman Senate thought the division was unfair. They said Ptolemy VIII should also get Cyprus. The historian Polybius believed the Senate wanted to weaken Egypt. Roman envoys were sent to make Ptolemy VI agree.

From Rome, Ptolemy VIII went to Greece. He hired soldiers to take Cyprus by force. He sailed to Rhodes with his fleet. There, he met the Roman envoys. They convinced him to send his troops home and return to Cyrene. He waited near the border of Egypt and Cyrene for the results of the Roman talks with Ptolemy VI. While he waited, the governor he left in Cyrene started a revolt. Ptolemy VIII marched to stop it but was defeated. He regained control of Cyrene by the end of 162 BC.

However, when the Roman envoys arrived in Alexandria, Ptolemy VI delayed them. When he heard about the revolt in Cyrene, he refused their demands. The envoys returned to Rome without success. In winter 162/61 BC, the Roman Senate broke off relations with Ptolemy VI. They gave Ptolemy VIII permission to use force to take Cyprus. But they did not offer him any real help. He launched a military trip to Cyprus in 161 BC. This trip lasted up to a year. Strong resistance from the Cypriots forced him to give up.

In 156 or 155 BC, someone tried to kill Ptolemy VIII, but failed. He blamed his older brother. Ptolemy VIII went to Rome and showed his scars to the Senate. As a result, the Roman Senate sent another group in 154 BC. They were meant to make Ptolemy VI give Cyprus to Ptolemy VIII. Ptolemy VIII was surrounded by his brother's forces at Lapethus and captured. He was convinced to leave Cyprus. In return, he kept Cyrenaica, received yearly payments of grain, and was promised marriage to one of Ptolemy VI's young daughters when she grew up.

- Friendship with Rome

While king of Cyrene, Ptolemy VIII had very close ties with Rome. From 162 BC, he was an official friend and ally of the Roman Republic. It is said that he met Cornelia in Rome. In 152 BC, after her husband died, Ptolemy VIII supposedly asked to marry her. She refused. This story was popular in art, but it probably never happened. Even if it's not true, it shows how close Ptolemy VIII was to important Roman families.

An old stone inscription from 155 BC talks about Ptolemy VIII's will. In it, he left Cyrenaica to Rome if he died without children. This act is not mentioned by other ancient writers. But it fits with his close relationship with the Romans. Other kings at that time also made similar wills. They often did this to protect themselves from being overthrown. Ptolemy VIII's will might be the earliest example of this practice.

- Showing Off Wealth

As king of Cyrene, Ptolemy VIII tried to show off his royal wealth and luxury. He became the main priest of Apollo in Cyrene. He performed his duties, especially hosting feasts, in a very grand way. He also started many building projects in the city. A large tomb west of Ptolemais seems to have been planned as his final resting place.

Second Time as King (145–132/1 BC)

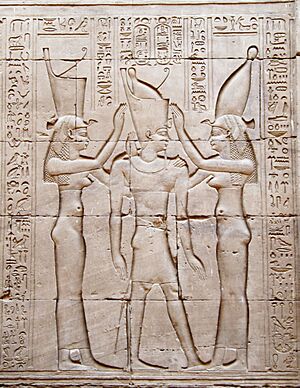

Ptolemy VI died in Syria in 145 BC. His seven-year-old son was meant to take over. But the people of Alexandria asked Ptolemy VIII to return from Cyrene. They wanted him to become king and marry his older sister, Cleopatra II. The royal couple were then called the Theoi Euergetai, meaning 'benefactor gods'. Ptolemy VIII became pharaoh in Memphis in 144 or 143 BC. Their only child, Ptolemy Memphites, was born during this time.

When Ptolemy VIII returned to Alexandria in 145 BC, he reportedly punished those who had opposed him. Ancient writings describe this as a very harsh time. It is hard to know if all the stories are true or if some belong to a later time. It was likely during this period that he got nicknames like Physkōn ("fatty") and Kakergetēs ("Malefactor"). This last name was a joke on his official title, Euergetēs ("Benefactor"). His return also meant the end of Egypt's power in the Aegean Sea. Within months, he pulled all troops from the last Egyptian bases there. The Egyptian empire was now only Egypt, Cyprus, and Cyrene.

Ptolemy VIII likely had his young nephew Ptolemy killed. According to one historian, Ptolemy VIII did it himself on his wedding night to Cleopatra II in 145 BC. The boy reportedly died in his mother's arms. However, other records suggest the boy was initially kept as heir. He was only removed after Ptolemy Memphites was born. By the late 140s BC, Ptolemy Memphites was declared heir. He was shown as king on temple carvings, but he did not rule with his father.

Between 142 and 139 BC, Ptolemy VIII married Cleopatra III. She was the daughter of Ptolemy VI and Cleopatra II. He made her a co-ruler, even though he was still married to Cleopatra II. This new marriage caused conflict with Cleopatra II.

Because of this new marriage, a mercenary captain named Galaestes started a revolt. Galaestes had been a trusted officer under Ptolemy VI. He had been forced to leave Egypt in 145 BC. In Greece, he gathered an army of other exiles. He claimed to have a young son of Ptolemy VI and crowned this boy as king. Galaestes attacked Ptolemy VIII. Ptolemy VIII's soldiers were almost ready to switch sides because they hadn't been paid. But their commander paid them with his own money. By February 139 BC, Galaestes was defeated. Ptolemy VIII then issued a decree. It said that he, Cleopatra II, and Cleopatra III were ruling together peacefully.

In the same year, Ptolemy VIII received Roman visitors. They were led by Scipio Aemilianus. Their goal was to bring peace to the Eastern Mediterranean. Ancient writers noted the very grand welcome the Romans received. This was often to show how simple the Romans were in comparison. By this time, Ptolemy VIII was reportedly very large and had to be carried everywhere.

Civil War (132–126 BC)

In late 132 BC, the conflict between the royal family members turned into an open war. Ptolemy VIII and Cleopatra III were on one side. Cleopatra II was on the other. At first, Ptolemy VIII controlled Alexandria. But in late 131 BC, the people of Alexandria rioted. They supported Cleopatra II and set fire to the royal palace. Ptolemy VIII, Cleopatra III, and their children escaped to Cyprus. Cleopatra II then crowned herself as the only queen. This was the first time a Ptolemaic woman had done this. She took a new title, linking her to her dead husband Ptolemy VI.

Even though Alexandria supported Cleopatra II, Ptolemy VIII and Cleopatra III were more popular with the native Egyptian people. Most of Egypt still recognized Ptolemy VIII as king. In the south, a man named Harsiesi started a rebellion. He declared himself Pharaoh and took control of Thebes in August or September 131 BC. He was forced out in November by an Egyptian general.

Ptolemy VIII and Cleopatra III returned from Cyprus to Egypt by early 130 BC. By spring, they controlled Memphis. They promoted the Egyptian general who had fought Harsiesi. This was the first time an Egyptian held such a high military position. Harsiesi was finally captured and killed in September 130 BC. Alexandria was surrounded, but Ptolemy VIII and Cleopatra III could not capture it. Cleopatra II also held strongholds throughout the country. During this struggle, Ptolemy VIII had his two oldest sons killed. One was called from Cyrene and killed because people thought the Alexandrians might make him king. The other, Ptolemy Memphites, was about twelve years old when his father killed him. Both sides asked Rome for help, but the Senate did not get involved.

Becoming desperate, Cleopatra II offered the throne of Egypt to her son-in-law in 129 BC. He was the Seleucid king Demetrius II. Demetrius II invaded Egypt in 128 BC. But his troops were still fighting near the border when he heard bad news. His wife, Cleopatra II's daughter, had made their son king of Syria. The Seleucid soldiers rebelled, and Demetrius II had to return to Syria.

To stop Demetrius II from coming back, Ptolemy VIII agreed to help rebels in Syria. They had asked him to send a royal leader. Ptolemy VIII chose Alexander II. He claimed Alexander II was the son of an earlier Seleucid king. The resulting conflict in Syria lasted for years. This meant that the Seleucids could no longer interfere against Ptolemy VIII.

In 127 BC, Cleopatra II took her money and fled Alexandria. She went to the court of Demetrius II. With her gone, Ptolemy VIII finally took back Alexandria by August 126 BC. This reconquest was followed by harsh punishment for Cleopatra II's supporters.

Third Time as King (127/6–116 BC)

After this, Ptolemy VIII started talks to make peace with Cleopatra II and the Seleucid court. In 124 BC, Ptolemy VIII stopped supporting Alexander II. He agreed to support Demetrius II's son, Antiochus VIII, instead. To seal the agreement, he sent his second daughter with Cleopatra III, Tryphaena, to marry Antiochus VIII. Cleopatra II returned to Egypt from the Seleucid court. She was again recognized as a co-ruler with Ptolemy VIII and Cleopatra III. She appears with them in official documents from July 124 BC onwards.

The reconciliation of Ptolemy VIII, Cleopatra III, and Cleopatra II took a long time. To make their peace stronger and bring calm to Egypt, the three rulers issued the Amnesty Decree in April 118 BC. Many copies of this decree still exist on papyrus. This decree forgave all crimes except murder and temple robbery committed before 118 BC. It encouraged people who had fled to return home and reclaim their property. It also canceled all old taxes. It confirmed land given to soldiers during the civil war. It protected temple lands and tax benefits. It also told tax officials to use standard weights and measures, or face severe punishment.

The decree also set rules for courts when Egyptians and Greeks had legal disagreements. From then on, the language of the documents would decide which court heard the case. Greek documents went to Greek judges. Egyptian documents went to Egyptian judges. Greek judges were no longer allowed to force Egyptians into their courts, which had happened before.

Ptolemy VIII died on June 28, 116 BC. His oldest surviving son, Ptolemy IX, took over. He ruled with Cleopatra II and Cleopatra III. One historian says Ptolemy VIII left the throne to Cleopatra III. He allowed her to choose which of her sons she preferred. Even though she preferred her younger son, Ptolemy X, the people of Alexandria forced her to choose Ptolemy IX. This story might be false, created later after Ptolemy IX was removed by Ptolemy X.

Royal Traditions

The Ptolemaic Royal Cult

Ancient Egypt had a special royal cult. It focused on a festival and an annual priest. This priest's full title included the names of all the ruling Ptolemaic kings and queens. Their names appeared in official documents as part of the date. In October 170 BC, when Ptolemy VIII first became co-ruler, he was added to the cult. He became a "Mother-loving God" with his brother and sister. When he took sole power in 164 BC, he seemed to use the new title Euergetēs ("Benefactor God"). After he was forced out in 163 BC, the "Mother-loving Gods" cult returned.

At the start of his second reign in 145 BC, Ptolemy VIII and Cleopatra II officially became the Theoi Euergetai ('Benefactor Gods'). Cleopatra III was added as a third Benefactor god in 142 or 141 BC. This was before she married Ptolemy VIII and became a co-ruler. During the civil war, Cleopatra II removed the Theoi Euergetai from the cult in Alexandria. But Ptolemy VIII and Cleopatra III kept their own rival priest from 130 BC. This continued until they took back Alexandria in 127 BC. The situation before the civil war was restored in 124 BC. This continued until Ptolemy VIII's death.

From May 118 BC, a new king was added to the royal cult. He was called Theos Neos Philopatōr ("New Father-loving God"). This was a special honor for one of the princes killed by Ptolemy VIII. Most scholars believe it was Ptolemy Memphites, Ptolemy VIII's son. This honor showed that the prince had made peace with his father after his death.

Since the death of Arsinoe II, dead Ptolemaic queens had their own separate cult. This included a priestess who marched in religious parades in Alexandria. Her name also appeared in dates. In 131 or 130 BC, Ptolemy VIII and Cleopatra III used this tradition. They created a new priesthood to honor Cleopatra III. This new position was called the 'Sacred Foal of Isis, Great Mother of the Gods'. It was placed very high in importance. This position was different because it was for a living queen, not a dead one. Also, the person holding it was a priest, not a priestess. This position is not mentioned after 105 BC.

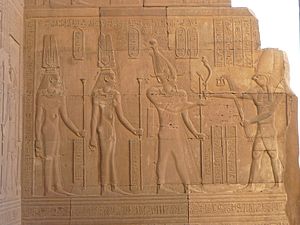

Egyptian Religion and Pharaoh's Role

From the very beginning, the Ptolemaic kings took on the traditional role of the Egyptian pharaoh. They worked closely with the Egyptian priests. The Ptolemies became more involved in this part of their rule over time. Ptolemy VIII marked a new step in this process. During his conflict with Cleopatra II, he was more popular with his Egyptian subjects than with his Greek ones.

In the Amnesty Decree of 118 BC, the three rulers promised to support rebuilding and repair work at temples across Egypt. They also promised to pay for the mummification and burial of the sacred Apis and Mnevis bulls.

Learning and Alexandria

Ptolemy VIII was interested in Greek learning, especially the study of language. He reportedly wrote a study about Homer before 145 BC. He also wrote twenty-four books of Hypomnemata ('Notes'). This was a collection of strange stories, including tales about kings, unusual animals, and other topics.

Despite his interest, Alexandria became less important as a center for learning during Ptolemy VIII's reign. This was partly due to the harsh actions he took when he gained control of the city in 145 BC and again in 126 BC. Many important thinkers were among his victims. Others were forced to leave Alexandria. Most of them moved to Athens or Rhodes.

Trade in the Indian Ocean

The Ptolemies had long used trading posts in the Red Sea. This allowed them to get gold, ivory, and elephants from the Horn of Africa. In the last years of Ptolemy VIII's reign, sailors discovered something important. They found that the yearly change in the Indian Monsoon Current allowed ships to cross the Indian Ocean in summer and return in winter. The first Greek to make this journey was Eudoxus of Cyzicus. He reportedly traveled to India in 118 BC and again in 116 BC.

This discovery made direct sea trade with India possible. Before this, trade between the Mediterranean and India relied on others. Sailors from Arabian centers would carry goods. Then, desert caravans would take them across the Arabian desert to the Mediterranean coast. After this discovery, sailors from Egypt began to make the full journey themselves. This marked the start of the Indian Ocean trade. It became a major part of the world's economy from the first century BC until the fourth century AD.

Family and Children

Ptolemy VIII married his older sister, Cleopatra II, when he became king in 145 BC. They had one son:

| Name | Image | Birth | Death | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

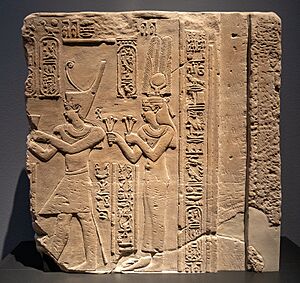

| Ptolemy Memphites | 144–142 BC | 130 BC | Killed by his father around 130 BC. He was shown as king in the Temple of Edfu. |

In 142 or 141 BC, Ptolemy VIII also married his niece Cleopatra III. She was the daughter of Ptolemy VI and Cleopatra II. They had several children:

| Name | Image | Birth | Death | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ptolemy IX |  |

142 BC | December 81 BC | Ruled Egypt with his mother and grandmother from 116 to 107 BC. He was sent away to Cyprus. He ruled Egypt again from 88 to 81 BC. |

| Ptolemy X |  |

140 BC? | 88-87 BC | King of Cyprus from 114 to 107 BC. He then ruled Egypt with his mother until 88 BC. |

| Tryphaena | c. 140 BC | 110/09 BC | Married the Seleucid king Antiochus VIII. | |

| Cleopatra IV | 138–135 BC? | 112 BC | Married her brother Ptolemy IX and ruled with him from 116 to 115 BC. She was then divorced and married the Seleucid king Antiochus IX. | |

| Cleopatra Selene |  |

135–130 BC? | 69 BC | Married Ptolemy IX from 115 BC. She later married three Seleucid kings. She eventually ruled as queen of Syria on her own. |

Ptolemy VIII also had another son with a different woman, possibly named Eirene:

| Name | Image | Birth | Death | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ptolemy Apion |  |

96 BC | King of Cyrenaica until 96 BC. |

How Kings Were Numbered

The way we number Ptolemaic kings today (like Ptolemy VIII) is a modern idea. In ancient times, people usually told kings apart by their nicknames or titles. For example, Ptolemy VIII Euergetes was called "Ptolemy Euergetes II" in some old lists.

Historians used to number kings differently. This was because of how royal names appeared in lists of deified (worshipped as gods) Ptolemies. For a while, Ptolemy Eupator was thought to be a king before Ptolemy VI. And Ptolemy Neos Philopator was thought to be a king before Ptolemy VIII. This would have changed Ptolemy VIII's number.

But we now know that the lists of deified kings showed the order of their death, not their rule. Ptolemy Eupator was a son who ruled with his father but never became the main king. So, he is not numbered. This left his father as "Ptolemy VI Philometor," and his uncle as "Ptolemy VIII Euergetes."

More recently, it was found that Ptolemy Neos Philopator was also never a main king. Even if he was Ptolemy VI's son and had ruled in 145 BC (which he didn't), Ptolemy VIII became king earlier. So, he would technically be "Ptolemy VII Euergetes." However, to avoid confusion with many existing books and studies, most scholars still call him "Ptolemy VIII Euergetes." To prevent confusion, it's best to use the king's title or nickname along with his number.

See also

In Spanish: Ptolomeo VIII para niños

In Spanish: Ptolomeo VIII para niños

| Claudette Colvin |

| Myrlie Evers-Williams |

| Alberta Odell Jones |