Rocky Flats Plant facts for kids

Quick facts for kids |

|

|

Rocky Flats Plant

|

|

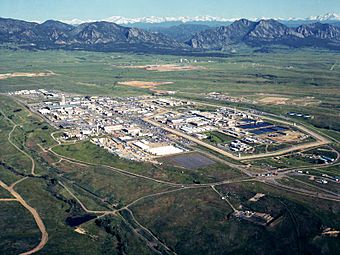

July 1995

|

|

| Location | Jefferson County, Colorado |

|---|---|

| Nearest city | Arvada, Colorado |

| Area | 175.8 acres (71.1 ha) |

| Built | 1952 |

| Built by | Austin Construction Co. |

| NRHP reference No. | 97000377 |

| Added to NRHP | May 19, 1997 |

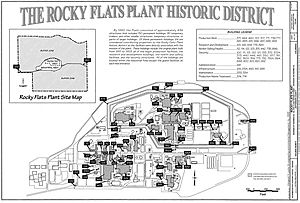

The Rocky Flats Plant was a factory in the western United States, near Denver, Colorado, that made parts for nuclear weapons. Its main job was to make special parts called plutonium "pits," which were then sent to other places to be put into nuclear weapons. The plant operated from 1952 to 1992. It was managed first by the U.S. Atomic Energy Commission (AEC) and later by the Department of Energy (DOE).

Making plutonium pits stopped in 1989 after agents from the EPA and FBI visited the factory. The plant officially closed in 1992. The company that ran the plant, Rockwell, later admitted to breaking environmental laws. They paid a large fine, which was one of the biggest for an environmental case at that time.

Cleanup of the site began in the early 1990s and finished in 2006. During the cleanup, over 800 buildings were taken down, more than 21 tons of weapons material were removed, and a lot of waste and water were treated. Today, the Rocky Flats Plant is gone. The area is now split into two parts:

- The "Central Operable Unit" (the old factory area) is still closed to the public. It is managed by the U.S. Department of Energy because it is a special cleanup site called a "Superfund" site.

- The Rocky Flats National Wildlife Refuge is open to the public. It is managed by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. This area was found to be safe for people to use.

Every five years, the U.S. Department of Energy, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), and the Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment check the site. They make sure the cleanup is still working as it should. The latest check in 2017 said the site is safe for people and the environment.

Contents

History of the Rocky Flats Plant

Starting the Plant in the 1950s

After World War II, the United States started making more nuclear weapons. The government chose the Dow Chemical Company to run a new factory. They picked a site about 15 miles (25 km) northwest of Denver. This windy area was called Rocky Flats. On July 10, 1951, construction began on the first building. News reports at the time said the site would not make bombs, but would produce parts for nuclear weapons.

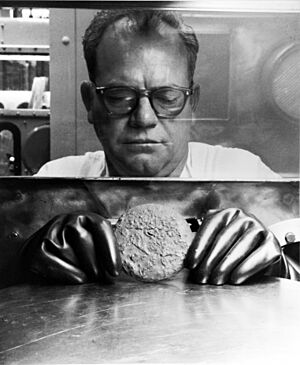

In 1953, the plant began making bomb parts. It produced plutonium "pits" that were sent to another factory in Amarillo, Texas, to build nuclear weapons. By 1957, the plant had grown to 27 buildings.

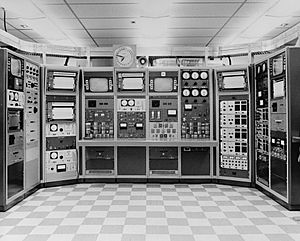

On September 11, 1957, a fire started in a special sealed box called a glovebox. These boxes are used to handle radioactive materials. The fire burned the rubber gloves and plastic windows of the box. Metallic plutonium can catch fire easily if the conditions are right. This accident contaminated Building 771 and released plutonium into the air. It caused about $818,600 in damage. In 1958, a special incinerator was installed to burn plutonium-contaminated waste.

In 1959, barrels of radioactive waste were found leaking into an open field. The public did not know about this until 1970, when tiny radioactive particles were found in Denver.

Events in the 1960s

Throughout the 1960s, the plant continued to grow and add more buildings. But it also had more contamination problems. In 1967, about 3,500 barrels (560 m3) of plutonium-contaminated oils and cleaning liquids were stored in an area called Pad 903. Many of these barrels were leaking. Low levels of contaminated soil from this area were being blown away by the wind. This pad was later covered with gravel and asphalt in 1969.

On May 11, 1969, a very large fire happened in a glovebox in Building 776/777. This was the most expensive industrial accident in the United States at that time. Cleaning up after the fire took two years. This led to better safety features at the plant, like fire sprinkler systems and firewalls.

Changes in the 1970s

To make the area safer and create a security zone around the plant, the United States Congress bought a 4,600-acre (7.2 sq mi; 19 km2) buffer zone in 1972. In 1973, nearby Walnut Creek and the Great Western Reservoir had high levels of tritium, a radioactive substance. This tritium came from contaminated materials sent to Rocky Flats from another lab.

When the Colorado Department of Health found this contamination, the AEC and EPA started investigations. As a result, new steps were taken to prevent more contamination. These included:

- Sending wastewater runoff to three dams for testing before it was released.

- Building a special facility to clean wastewater using a process called reverse osmosis.

The next year, high plutonium levels were found in the topsoil near the now-covered Pad 903. Another 4,500 acres (7.0 sq mi; 18 km2) of land was bought for the buffer zone.

In 1975, Rockwell International took over from Dow Chemical as the company running the plant. This year, local landowners also sued the plant because their properties were contaminated.

In 1978, 60 protesters from the Rocky Flats Truth Force were arrested for going onto the Rocky Flats property. A doctor testified that the biggest danger of contamination came from the 1967 incident where oil barrels leaked plutonium into sand. Strong winds then blew this sand as far as Denver.

Dr. Carl Johnson, a health director for Jefferson County, studied contamination levels and health risks from the plant. He was against building homes near Rocky Flats and was later fired. While some of his findings were later supported, a court in 1985 found his studies "unreliable." The court agreed that there was "no measurable increases in cancer incidence" from the plant's operations.

On April 28, 1979, after the Three Mile Island accident, about 15,000 protesters gathered near the plant. Singers Jackson Browne and Bonnie Raitt performed. The next day, 286 protesters, including Daniel Ellsberg, were arrested for civil disobedience on the plant's property.

The 1980s and Plant Protests

On December 11, 1980, Congress passed a law to help clean up the nation's worst environmental sites.

Dark Circle is a 1982 documentary film about the Rocky Flats Plant and its plutonium contamination. The film won awards, including an Emmy Award.

Rocky Flats became a major focus for peace activists in the 1980s. In 1983, 17,000 people joined hands around the 17-mile (27 km) perimeter of the plant in a large demonstration.

A security zone was added around the plant in 1983 and improved in 1985. Also in 1983, the plant processed its first radioactive waste using a new system, creating a plutonium button.

In 1985, employees celebrated 250,000 continuous safe hours. Rockwell also received an award for a process that removed contamination from wastewater. The next year, the site received a safety award.

In 1986, the State of Colorado, EPA, and DOE agreed to work together to make sure the plant followed environmental laws. This agreement also started the process of investigating and cleaning up environmental contamination.

On August 10, 1987, 320 protesters were arrested after trying to force a one-day shutdown of the plant.

In 1988, a report from the Department of Energy (DOE) criticized the plant's safety measures. The EPA fined the plant for leaks of a chemical called polychlorinated biphenyl (PCB). A solid waste form, called pondcrete, was found to be leaking. A boxcar of radioactive waste from the site was sent back after Idaho refused to accept it. Plans to possibly close the plant were also discussed.

In 1989, an employee left a faucet running, causing a chemical called chromic acid to leak into the water system. The Colorado Department of Health and the EPA then placed full-time staff at the plant to watch over safety. Plutonium production was stopped because of safety problems.

In August 1989, about 3,500 people took part in another protest at Rocky Flats.

FBI and EPA Investigation

Starting in 1987, people working at the plant secretly told the EPA and FBI about unsafe conditions. In December 1988, the FBI began flying planes over the area. Using special cameras, they saw that an old incinerator, which was not allowed to be used, was still being operated late at night. After months of gathering evidence from workers and direct measurements, the FBI told the DOE on June 6, 1989, that they wanted to meet.

On June 6, 1989, a court issued a search warrant to the FBI. This was partly based on information from Colorado Department of Health inspectors.

The raid, called "Operation Desert Glow," began at 9 a.m. on June 6, 1989. When FBI agents arrived for the meeting, they told the surprised DOE and Rockwell officials the real reason for their visit. The FBI found many violations of federal anti-pollution laws, including contamination of water and soil. In 1992, Rockwell International was charged with environmental crimes. Rockwell admitted guilt and paid an $18.5 million fine. This was the largest fine for an environmental crime at that time.

After the FBI raid, a special grand jury was formed in Colorado. This jury heard from 110 witnesses and reviewed many documents. The grand jury wanted to release a report to the public, but the U.S. Justice Department kept it secret. However, parts of the report were leaked to a newspaper. According to these leaks, the grand jury had planned to charge three DOE officials and five Rockwell employees with environmental crimes. The grand jury also said that Rocky Flats had released pollutants and radioactive materials into nearby creeks and water supplies for many years.

Even the DOE itself, in a study before the FBI raid, had called Rocky Flats' groundwater the biggest environmental danger at any of its nuclear sites.

Cleanup and Transformation in the 1990s

EG&G replaced Rockwell International as the main company for the Rocky Flats plant. EG&G started a strong safety and cleanup plan. This included building a system to remove contamination from the site's groundwater. A court case, Sierra Club vs. Rockwell, ruled that Rocky Flats had to manage plutonium waste as hazardous waste.

In 1991, an agreement between DOE, the Colorado Department of Health, and the EPA set up plans for environmental cleanup. The DOE also suggested making the plant smaller. Because the Soviet Union had fallen apart, many of the weapons made at Rocky Flats were no longer needed.

In 1992, President G. H. W. Bush ordered that production of certain submarine-based missiles stop. This led to 4,500 employees being laid off at the plant. However, 4,000 others stayed to work on the long-term cleanup. The DOE announced that about 61 pounds (28 kg) of plutonium was found in the exhaust ductwork of six buildings.

Starting in 1993, weapons-grade plutonium began to be shipped to other national laboratories and sites for storage.

In 1994, the site was renamed the Rocky Flats Environmental Technology Site. This showed that its purpose had changed from making weapons to cleaning up the environment. The cleanup work was given to the Kaiser-Hill Company. They suggested opening 4,100 acres (6.4 sq mi; 16.6 km2) of the buffer zone to the public.

In 1998, the Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment's Cancer Registry studied cancer rates around Rocky Flats. The study found no pattern of increased cancers linked to the plant.

Throughout the rest of the 1990s and into the 2000s, contaminated areas were cleaned up, and contaminated buildings were taken apart. The waste materials were sent to other special facilities across the country.

The 2000s: A New Purpose

In 2001, Congress passed the Rocky Flats National Wildlife Refuge Act. In July 2007, the U.S. Department of Energy gave almost 4,000 acres (6 sq mi; 16 km2) of land at Rocky Flats to the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. This land became the Rocky Flats National Wildlife Refuge. Studies of the site have found 630 types of vascular plants, most of which are native. Herds of elk are often seen there. However, the DOE kept control of the central area, where the factory used to be.

The last contaminated building was removed, and the last weapons-grade plutonium was shipped out in 2003. This marked the end of the main cleanup work. The cleanup agreement was changed to require a higher level of cleanup in the top 3 feet (0.9 m) of soil. In return, they did not have to remove contamination deeper down, unless it could move to the surface or contaminate groundwater. By 2006, all 800 buildings had been taken down. Today, the plant and all its buildings are gone.

The site still has some plutonium left from fires and other releases. Another main contaminant is carbon tetrachloride (CCl4). Both of these substances affected areas next to the site. There were also small releases of beryllium, tritium, and dioxin from burning waste.

The cleanup was declared complete on October 13, 2005. About 1,300 acres (2 sq mi; 5 km2) of the original site, the former industrial area, is still managed by the U.S. DOE. This area is used for ongoing environmental checks and cleanup. In 2007, the DOE, EPA, and Colorado health department signed an agreement to manage the site and protect human health and the environment.

Because the wildlife refuge area was found to be safe for people to use, the EPA removed it from its list of "Superfund" sites in 2007.

The 2010s and Ongoing Discussions

In September 2010, after a 20-year legal battle, a court reversed a large award in a class-action lawsuit against Dow Chemical and Rockwell International. The court said the jury's decision was based on incorrect instructions. The case was sent back to a lower court. The appeals court said that the owners of 12,000 properties had not proven their properties were damaged or that they were harmed by plutonium from the plant.

In response to reports of health issues from people living near Rocky Flats, an online health survey was started in May 2016. This survey aimed to gather information from thousands of Coloradans who lived east of the plant when it was running.

On May 19, 2016, a $375 million agreement was reached. This settled claims from over 15,000 nearby homeowners who said plutonium releases from the plant risked their health and lowered their property values. This ended a 26-year legal battle between residents and the two companies that ran the plant.

June 2014 marked 25 years since the FBI and EPA raid. A three-day event called "Rocky Flats Then and Now: 25 Years After the Raid" took place. It included discussions, historical photos, and art inspired by Rocky Flats.

In 2016, the Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment's Cancer Registry completed a study on cancer rates around Rocky Flats from 1990 to 2014. This study followed up on an earlier one from 1998. It looked at cancers linked to plutonium and other cancers of concern. The study found that "the number of all cancers-combined for both adults and children was no different in the communities around Rocky Flats than expected" compared to the rest of the Denver area.

In 2017, a follow-up study looked at thyroid and rare cancers. It found "no evidence of higher than expected frequencies of thyroid cancer" and that "the incidence of 'rare' cancer was not higher than expected."

In 2018, Metropolitan State University of Denver decided not to continue participating in the health survey.

In January 2019, activist groups who questioned the safety assessment for the wildlife refuge filed a lawsuit. They wanted to unseal documents from the grand jury investigation.

In response to concerns about breast cancer in young women, the Cancer Registry also looked at breast cancer rates in young women near Rocky Flats. In October 2019, they shared their findings. The Cancer Registry concluded that "no increased incidence of breast cancer was found in young women in communities around Rocky Flats."

The 2020s and Beyond

For more information on remaining issues and updates, see Radioactive contamination from the Rocky Flats Plant.

See also

In Spanish: Planta de Rocky Flats para niños

In Spanish: Planta de Rocky Flats para niños

| DeHart Hubbard |

| Wilma Rudolph |

| Jesse Owens |

| Jackie Joyner-Kersee |

| Major Taylor |