SS Edmund Fitzgerald facts for kids

class="infobox " style="float: right; clear: right; width: 315px; border-spacing: 2px; text-align: left; font-size: 90%;"

| colspan="2" style="text-align: center; font-size: 90%; line-height: 1.5em;" |

|} The SS Edmund Fitzgerald was a huge American cargo ship that sailed the Great Lakes. On November 10, 1975, she sank during a terrible storm on Lake Superior. All 29 crew members were lost.

When she was launched in 1958, the Edmund Fitzgerald was the longest ship on the Great Lakes. She still holds the record as the largest ship ever to sink there. Divers found her wreckage on November 14, 1975. She was in two large pieces at the bottom of the lake.

For 17 years, the Edmund Fitzgerald carried taconite (a type of iron ore) from mines in Minnesota. She delivered it to steel factories in Detroit, Michigan, Toledo, Ohio, and other Great Lakes ports. She was a very busy ship and set new cargo records six times.

Captain Peter Pulcer, one of her captains, was famous for playing music over the ship's speakers. He would do this while passing through the St. Clair River and Detroit River. He also entertained people at the Soo Locks with fun facts about the ship. Because of her size, records, and "DJ captain," the Edmund Fitzgerald was a favorite among people who watched ships.

Contents

| History | |

|---|---|

| Name | SS Edmund Fitzgerald |

| Namesake | Edmund Fitzgerald, president of Northwestern Mutual |

| Owner | Northwestern Mutual Life Insurance Company |

| Operator | |

| Port of registry | Milwaukee, Wisconsin |

| Ordered | February 1, 1957 |

| Yard number | 301 |

| Laid down | August 7, 1957 |

| Launched | June 7, 1958 |

| Maiden voyage | September 24, 1958 |

| In service | June 8, 1958 |

| Out of service | November 10, 1975 |

| Identification | Registry number US 277437 |

| Nickname(s) | Fitz, Mighty Fitz, Big Fitz, Pride of the American Side, Toledo Express, Titanic of the Great Lakes |

| Fate | Lost with all hands (29 crew) in a storm, November 10, 1975 |

| Status | Wreck |

| Notes | Location of wreck: 46°59′54″N 85°6′36″W / 46.99833°N 85.11000°W |

| General characteristics | |

| Type | Lake freighter |

| Tonnage |

|

| Length |

|

| Beam | 75 ft (23 m) |

| Draft | 25 ft (7.6 m) typical |

| Depth | 39 ft (12 m) (moulded) |

| Depth of hold | 33 ft 4 in (10.16 m) |

| Installed power |

|

| Propulsion | Single fixed pitch 19.5 ft (5.9 m) propeller |

| Speed | 14 kn (26 km/h; 16 mph) |

| Crew | 29 |

- Waves and Weather

- Rogue Wave Idea

- Cargo Hold Flooding Idea

- Hitting a Shoal Idea

- Structural Failure Idea

- Topside Damage Idea

- Weather Forecasting Issues

- Inaccurate Maps

- No Watertight Walls

- Missing Equipment

- Increased Cargo Limits

- Maintenance Issues

- Overconfidence

History of the Ship

Building the Fitzgerald

The Northwestern Mutual Financial Network company paid for the Edmund Fitzgerald to be built. It was a big investment for them. In 1957, they hired Great Lakes Engineering Works in River Rouge, Michigan, to design and build the ship. They wanted it to be almost as long as possible to fit through the new Saint Lawrence Seaway.

The ship cost $7 million to build, which would be a lot more money today. The Edmund Fitzgerald was the first "laker" (Great Lakes ship) built to the maximum size for the St. Lawrence Seaway. This meant she was 729 feet (222 m) long, 75 feet (23 m) wide, and could sit 25 feet (7.6 m) deep in the water.

The ship's main body, called the moulded depth, was 39 ft (12 m) high. The cargo hold, where the ore was kept, was 33 ft 4 in (10.16 m) deep. The first part of her keel (the bottom structure) was laid down on August 7, 1957.

The Edmund Fitzgerald could carry 26,000 long tons (26,000 t) of cargo. She was the longest ship on the Great Lakes until 1959. Her three cargo holds were loaded through 21 large, waterproof cargo hatches. Each hatch was 11 by 48 feet (3.4 by 14.6 m) and made of thick steel.

At first, the ship burned coal for power. But in the winter of 1971–72, she was changed to burn oil instead. In 1969, a bow thruster was added to help her steer better.

The inside of the Edmund Fitzgerald was quite fancy for a cargo ship. It had soft carpets, tiled bathrooms, and leather chairs for guests. There were two guest rooms for visitors. Even the crew's living areas had air conditioning and more comforts than usual. The ship had a large kitchen, called a galley, and two dining rooms. The pilothouse, where the ship was steered, had the newest navigation equipment.

Naming and Launching

Northwestern Mutual wanted to name the ship after their president, Edmund Fitzgerald. His family had a history with ships. His grandfather and great-uncles were lake captains, and his father owned a company that built and repaired ships. Mr. Fitzgerald tried to suggest other names, but the company board voted to name it after him.

More than 15,000 people came to the ship's launch ceremony on June 7, 1958. The event had some bad luck. When Edmund Fitzgerald's wife, Elizabeth, tried to break a champagne bottle on the ship's bow, it took her three tries. Then, it took 36 minutes for the shipyard crew to release the ship from its blocks.

When the ship finally slid sideways into the water, it made a huge wave. This wave splashed all over the people watching. The ship then crashed into a pier before straightening itself. Some witnesses even said the ship looked like it was "trying to climb right out of the water." Despite these issues, the Edmund Fitzgerald finished her sea trials on September 22, 1958.

Ship's Career

Northwestern Mutual usually bought ships for other companies to operate. For the Edmund Fitzgerald, they signed a 25-year contract with Oglebay Norton Corporation. This company immediately made the Edmund Fitzgerald the main ship of its Columbia Transportation fleet.

The Edmund Fitzgerald was a very busy and successful ship. She often broke her own records for how much cargo she carried. In 1969, she carried her biggest load ever: 27,402 long tons (27,842 t). For 17 years, she moved taconite from Minnesota's Iron Range to cities like Detroit and Toledo. She set seasonal cargo records six times.

People gave her many nicknames, like "Fitz," "Mighty Fitz," and "Titanic of the Great Lakes." Loading the ship with ore pellets took about four and a half hours. Unloading took around 14 hours. A round trip from Superior, Wisconsin, to Detroit usually took five days. She made about 47 such trips each season. By November 1975, she had traveled over a million miles. That's like going around the world 44 times!

Passengers sometimes traveled on the ship as guests. They were treated very well with excellent food and drinks. The captain even held special dinners for them.

Because of her size and records, the Edmund Fitzgerald was popular with boat watchers. Captain Peter Pulcer was known for playing music over the ship's speakers. He would also use a bullhorn to talk to tourists at the Soo Locks.

In 1969, the Edmund Fitzgerald won a safety award for eight years without a worker injury. However, she did have some small accidents. She ran aground in 1969 and hit another ship in 1970. She also hit a lock wall in 1973 and 1974. In 1974, she lost her front anchor in the Detroit River. None of these were seen as serious problems. Great Lakes ships are built to last over 50 years, so the Edmund Fitzgerald was expected to have a long career.

Final Voyage and Sinking

The Edmund Fitzgerald left Superior, Wisconsin, at 2:15 p.m. on November 9, 1975. Captain Ernest M. McSorley was in charge. She was heading to a steel mill near Detroit, Michigan. She carried 26,116 long tons (26,535 t) of taconite ore pellets. Soon, she reached her top speed of 16.3 miles per hour (26.2 km/h).

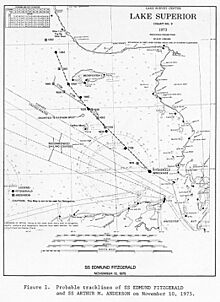

Around 5 p.m., the Edmund Fitzgerald joined another cargo ship, the SS Arthur M. Anderson. This ship was also carrying taconite. The weather forecast was normal for November. The National Weather Service (NWS) said a storm would pass south of Lake Superior.

Another ship, the SS Wilfred Sykes, left about two hours after the Edmund Fitzgerald. Its captain, Dudley J. Paquette, thought a big storm would hit Lake Superior directly. So, he chose a route that would protect his ship. The crew of the Wilfred Sykes listened to the radio calls between the Edmund Fitzgerald and the Arthur M. Anderson. They heard the captains decide to take the usual route.

At 7:00 p.m., the NWS changed its forecast. They issued gale warnings (strong wind warnings) for all of Lake Superior. The Arthur M. Anderson and Edmund Fitzgerald changed course to the north. They looked for shelter along the Canadian shore. But at 1:00 a.m. on November 10, they ran into a winter storm.

The Edmund Fitzgerald reported winds of 52 knots (96 km/h; 60 mph) and waves 10 feet (3.0 m) high. Captain Paquette of the Wilfred Sykes heard Captain McSorley say he had slowed down because of the rough conditions. Paquette was surprised because McSorley usually didn't slow down. McSorley said, "we're going to try for some shelter from Isle Royale."

At 2:00 a.m. on November 10, the NWS upgraded its warnings to a full storm. They predicted winds of 35–50 knots (65–93 km/h; 40–58 mph). The Edmund Fitzgerald had been following the Arthur M. Anderson, but she pulled ahead around 3:00 a.m. As the storm passed over the ships, the winds changed direction and got stronger.

After 1:50 p.m., the Arthur M. Anderson recorded winds of 50 knots (93 km/h; 58 mph). It started snowing at 2:45 p.m., making it hard to see. The Arthur M. Anderson lost sight of the Edmund Fitzgerald, which was about 16 miles (26 km) ahead.

Shortly after 3:30 p.m., Captain McSorley radioed the Arthur M. Anderson. He reported that the Edmund Fitzgerald was taking on water. She had lost two vent covers and a fence railing. The ship was also leaning to one side, called a list. Two of her bilge pumps (which remove water) were running all the time. McSorley said he would slow down so the Arthur M. Anderson could catch up.

The United States Coast Guard (USCG) warned all ships that the Soo Locks were closed. They told ships to find a safe place to anchor. Around 4:10 p.m., McSorley called the Arthur M. Anderson again. He said his radar had failed and asked the Arthur M. Anderson to track them. The Edmund Fitzgerald, now blind, slowed down so the Arthur M. Anderson could get within 10 miles (16 km) and guide her.

For a while, the Arthur M. Anderson guided the Edmund Fitzgerald toward Whitefish Bay, a safer area. Then, at 4:39 p.m., McSorley asked the USCG if the Whitefish Point Light and navigation beacon were working. The USCG said they were not. McSorley then asked other ships in the area. Captain Cedric Woodard of the Avafors said the light was on, but not the radio beacon. Woodard heard McSorley say, "Don't allow nobody on deck." He also heard something about a vent. Later, McSorley told Woodard, "I have a 'bad list', I have lost both radars, and am taking heavy seas over the deck in one of the worst seas I have ever been in."

By late afternoon on November 10, winds over 50 knots (93 km/h; 58 mph) were recorded across eastern Lake Superior. The Arthur M. Anderson recorded winds as high as 58 knots (107 km/h; 67 mph) at 4:52 p.m. Waves grew to 25 feet (7.6 m) by 6:00 p.m. The Arthur M. Anderson was also hit by gusts of 70 to 75 knots (130 to 139 km/h; 81 to 86 mph) and huge rogue waves up to 35 feet (11 m).

At about 7:10 p.m., the Arthur M. Anderson asked the Edmund Fitzgerald how she was doing. McSorley replied, "We are holding our own." This was the last message ever heard from the ship. No distress signal was sent. Ten minutes later, the Arthur M. Anderson could no longer reach the Edmund Fitzgerald by radio or see her on radar.

The Search and Discovery

Captain Cooper of the Arthur M. Anderson first called the USCG at 7:39 p.m. He used the emergency radio channel. The USCG told him to call back on another channel. Cooper then called another ship, the Nanfri, which also couldn't find the Edmund Fitzgerald on its radar. Cooper kept trying to reach the USCG and finally got through at 7:54 p.m. The officer asked him to look for a small boat that was lost.

Around 8:25 p.m., Cooper called the USCG again to say he was worried about the Edmund Fitzgerald. At 9:03 p.m., he reported her missing. A USCG officer later said he thought it was serious, but not urgent at that moment.

The USCG didn't have enough rescue ships ready. So, around 9:00 p.m., they asked the Arthur M. Anderson to turn around and look for survivors. Around 10:30 p.m., the USCG asked all commercial ships in Whitefish Bay to help. The Arthur M. Anderson and another ship, the SS William Clay Ford, started searching. A third ship, the SS Hilda Marjanne, couldn't help because of the bad weather.

The USCG sent a buoy tender (a ship that maintains buoys), the Woodrush. But it took a long time to launch and travel to the search area. A USCG search plane arrived at 10:53 p.m. A USCG helicopter arrived at 1:00 a.m. on November 11. Canadian aircraft also joined the three-day search. Police patrolled the eastern shore of Lake Superior.

They found some debris, like lifeboats and rafts, but none of the 29 crew members were found. The crew included the captain, mates, engineers, cooks, and deckhands. Their ages ranged from 20 to 63. Most were from Ohio and Wisconsin.

The Edmund Fitzgerald is one of the most famous ships lost on the Great Lakes. But many other ships have sunk in that area. Between 1816 and 1975, at least 240 ships were lost near Whitefish Point.

Finding the Wreck

A U.S. Navy plane found the wreck on November 14, 1975. The plane could detect magnetic anomalies (changes in the Earth's magnetic field), which helped locate the ship. The Edmund Fitzgerald lay about 15 miles (24 km) west of Deadman's Cove, Ontario. She was in Canadian waters, 530 feet (160 m) deep.

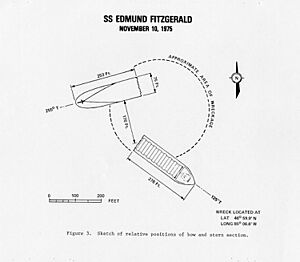

Another survey by the USCG from November 14–16 used side scan sonar. This showed two large objects close together on the lake floor. The U.S. Navy did another survey from November 22–25.

Underwater Explorations

From May 20–28, 1976, the U.S. Navy used an unmanned submersible called CURV-III to dive to the wreck. They found the Edmund Fitzgerald in two large pieces. The front part, the bow, was 276 feet (84 m) long and stood upright in the mud. The back part, the stern, was 253 feet (77 m) long and lay upside down. It was about 170 feet (52 m) from the bow. Between the two pieces was a lot of ore pellets and scattered wreckage.

In 1980, explorer Jean-Michel Cousteau (son of Jacques Cousteau) sent divers in a manned submersible to the wreck. They thought the ship had broken apart on the surface.

In 1989, the Michigan Sea Grant Program organized another dive. They used a special underwater robot called an ROV to record 3-D video. This video was used for museum programs and documentaries.

Canadian explorer Joseph B. MacInnis led more dives in 1994. He used a manned submersible. His team concluded that their findings didn't fully explain why the ship sank. That same year, Fred Shannon led a privately funded dive. His team took over 42 hours of underwater video. Shannon found that the two main parts of the ship were 255 feet (78 m) apart. This led him to believe the ship broke apart on the surface.

Shannon's group also found the remains of a crew member wearing a life jacket near the bow. This showed that at least one crew member knew the ship might sink.

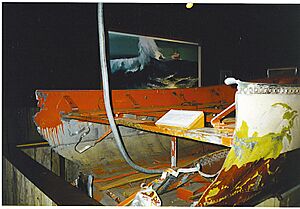

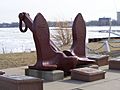

In 1995, MacInnis led another dive to bring up the ship's bell. They replaced it with a replica. The Sault Tribe of Chippewa Indians helped fund this. The bell is now on display at the Great Lakes Shipwreck Museum.

What Caused the Sinking?

Bad weather and huge waves played a role in all the ideas about why the Edmund Fitzgerald sank. But experts have different ideas about other causes.

Waves and Weather

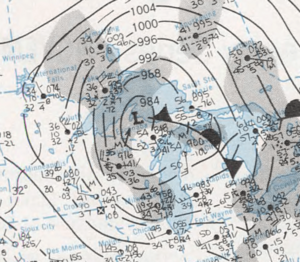

In 2005, NOAA and the NWS used computers to recreate the storm. Their study showed two areas of very high winds over Lake Superior at 4:00 p.m. on November 10. Winds were over 40 knots (74 km/h; 46 mph). The area where the Edmund Fitzgerald was heading had the strongest winds.

Average wave heights grew to almost 19 feet (5.8 m) by 7:00 p.m. Winds were over 50 mph (80 km/h) across most of southeastern Lake Superior. The Edmund Fitzgerald sank at the edge of this high-wind area. The long distance the wind blew over the water, called the fetch, created huge waves. These waves averaged over 23 feet (7.0 m) by 7:00 p.m. and over 25 feet (7.6 m) by 8:00 p.m. The simulation also showed that some waves could reach 36 feet (11 m), and even 46 feet (14 m). Since the ship was sailing east-southeast, these waves likely made her roll heavily.

The Arthur M. Anderson reported winds of 57 mph (92 km/h) at the time of the sinking. The computer model showed winds of 54 mph (87 km/h). The model also showed that the strongest winds reached almost hurricane force, about 70 mph (110 km/h), with gusts up to 86 miles per hour (138 km/h). This was at the exact time and place where the Edmund Fitzgerald sank.

Rogue Wave Idea

Some people believe a group of three huge waves, called "three sisters," hit the Edmund Fitzgerald. A "three sisters" event is when three very large waves form, each about one-third bigger than normal waves. The first wave puts a lot of water on the ship's deck. This water doesn't drain away before the second wave hits, adding more water. The third wave then adds even more, quickly overloading the deck.

Captain Cooper of the Arthur M. Anderson said his ship was "hit by two 30 to 35 foot seas about 6:30 p.m." He said these waves, possibly followed by a third, continued toward the Edmund Fitzgerald. They would have hit around the time she sank. This idea suggests that these "three sisters" made the ship's problems worse. The Edmund Fitzgerald was already leaning and moving slower in the heavy seas. This meant water stayed on her deck longer than usual.

A TV show called Dive Detectives showed a model of the Edmund Fitzgerald in a wave tank. It showed how a 17 metres (56 ft) rogue wave could almost completely cover the ship's front or back with water.

Cargo Hold Flooding Idea

A USCG report in 1977 suggested the ship sank because the hatch covers didn't seal properly. They thought waves slowly filled the cargo hold with water. This would have caused the ship to lose its ability to float and become unstable. The ship would have sunk suddenly without warning. However, video of the wreck showed most hatch clamps were in good condition. The USCG thought only a few clamps were fastened. This would have allowed water to get in.

Some families of the crew and worker groups thought the USCG's findings might be unfair. They believed the USCG was trying to avoid blame for its own rules and inspections. The Lake Carriers Association (LCA), which represents ship owners, disagreed with the USCG. They said the hatch covers were very good and had worked well for almost 40 years without any ships sinking.

It was common for ships to sail without all hatch clamps locked in fine weather. Captain Paquette of the Wilfred Sykes said that unlocked clamps would not have caused the Edmund Fitzgerald to sink.

The National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB) had different findings in 1978. They looked at the wreck and found that some hatch covers were missing or damaged. They believed the Edmund Fitzgerald sank suddenly because giant waves collapsed one or more hatch covers. This would have flooded the cargo hold very quickly.

Hitting a Shoal Idea

The LCA believed the Edmund Fitzgerald hit a shoal (a shallow area) northwest of Caribou Island. They thought the ship "unknowingly raked a reef" when the Whitefish Point light and radio beacon were not working. A 1976 survey found that a shoal extended farther east than shown on old maps. Officers from the Arthur M. Anderson saw the Edmund Fitzgerald sail through this area.

This idea suggests that the ship's front and back bent downwards, and the middle part lifted up when it hit the shoal. This could have pulled the fence railing tight until it broke. However, divers searched the Six Fathom Shoal after the wreck and found no signs of a recent collision. Photos of the wreck also showed no damage to the ship's bottom, propeller, or rudder that would suggest it hit a shoal.

Some people thought the LCA supported this idea to protect shipping companies and the USCG from blame.

Another idea was that the Edmund Fitzgerald hit Superior Shoal at 9:30 a.m. on November 10. This shoal is an underwater mountain in the middle of Lake Superior. It has sharp peaks that are close to the surface. A large wave, called a seiche, happened during the storm. This wave caused the lake level to rise. This idea suggests the ship hit the shoal, puncturing its hull. The ship then broke apart on the surface.

Structural Failure Idea

Another idea is that the ship's structure was already weak. Also, changes allowed the ship to carry more cargo and sit lower in the water. This made it easier for large waves to cause a crack in the hull. This idea doesn't necessarily involve "rogue waves."

The USCG and NTSB looked into whether the Edmund Fitzgerald broke apart because of structural failure. Since the two parts of the wreck were 170 feet (52 m) apart, the USCG thought the ship broke when it hit the lake floor. The NTSB agreed. They believed the ship sank in one piece and then broke apart.

However, other experts believe the ship broke in two on the surface before sinking. This is similar to other ore carriers that sank. After reviewing video from a 1989 survey, historian Frederick Stonehouse thought the stern (back) floated for a short time. It spilled ore into the front section. This means the two parts didn't sink at the same time. The 1994 Shannon team found the stern and bow were 255 feet (78 m) apart. Shannon concluded the ship broke up on the surface.

Former crew members also supported the idea of structural failure. Richard Orgel, a former second mate, said the ship "had a tendency to bend and spring during storms." He saw cracks in the paint that showed stress. George H. "Red" Burgner, the ship's steward, said the "keel" (bottom structure) was "tack welded" and many welds were broken.

The Edmund Fitzgerald and her sister ship, the SS Arthur B. Homer, were built with welded joints instead of riveted ones. Riveted joints allow a ship to flex in heavy seas, but welded joints are more likely to break. The Arthur B. Homer was taken out of service just five years after being lengthened. This raised questions about whether both ships had similar structural problems.

A naval architect who worked on the Edmund Fitzgerald's design, Raymond Ramsay, believed the ship was not safe to sail on November 10, 1975. He said the ship's long design, combined with its all-welded hull, made it too flexible. He thought the hull should have been made stronger for its length.

Topside Damage Idea

The USCG also thought damage to the ship's top deck could have caused the sinking. They thought a heavy floating object, like a log, might have damaged the fence rail and vents. Historian Mark Thompson believes something broke loose from the deck. He thought the lost vents could have flooded two ballast tanks, causing the ship to lean. Thompson also thought more damage than Captain McSorley could see might have let water into the cargo hold. He concluded that the damage to the ship's top, combined with the heavy seas, was the most likely reason she sank.

Possible Contributing Factors

Many things might have contributed to the sinking of the Edmund Fitzgerald.

Weather Forecasting Issues

The NWS forecast on November 9, 1975, said a storm would pass south of Lake Superior. But Captain Paquette of the Wilfred Sykes had been tracking the storm since November 8. He believed a major storm would hit Lake Superior directly. So, he chose a safer route.

Based on the NWS forecast, the Arthur M. Anderson and Edmund Fitzgerald took the usual route. This put them right in the storm's path. The NTSB concluded that the NWS didn't accurately predict the wave heights. A later study in 2005 said the Edmund Fitzgerald "ended in precisely the wrong place at the absolute worst time."

Inaccurate Maps

The USCG found that the Canadian navigation map for the Six Fathom Shoal area was based on old surveys from 1916 and 1919. A 1976 survey found that the shoal extended about 1 mile (1.6 km) farther east than shown on the maps. The NTSB concluded that the maps were not detailed enough to show the shoal as a danger.

No Watertight Walls

Mark Thompson, a sailor and author, said that if the ship's cargo holds had watertight walls, the Edmund Fitzgerald could have made it to Whitefish Bay. Frederick Stonehouse also believed the lack of these walls caused the sinking. He called Great Lakes ore carriers "motorized barges" with "virtually no watertight integrity." He said a small hole could sink them.

After the sinking, some people accused shipping companies of caring more about cargo than human lives. The ship's cargo hold was divided by only two non-watertight walls. The NTSB said Great Lakes ships should have watertight walls in their cargo holds.

The USCG had suggested rules for watertight walls after another ship sank in 1966. They did so again after the Edmund Fitzgerald sank. But ship owners argued it would cost too much money. Some ships built after 1975 have watertight walls, but most older ships on the lakes still don't.

Missing Equipment

The Edmund Fitzgerald did not have a fathometer (a device to measure water depth). USCG rules didn't require one. Instead, the ship used a hand line (a rope with a weight) to measure depth. The NTSB said a fathometer would have given the ship more navigation information. It would have made her less reliant on the Arthur M. Anderson.

The ship also had no way to check for water in her cargo hold. It would have been impossible to access the hatches during the storm. The USCG said the crew wouldn't have known about flooding until water reached the top of the ore. The ship also lacked a system to read how deep she was in the water. So, the crew couldn't tell if the ship was losing freeboard (how high the deck is above the water).

Increased Cargo Limits

The USCG allowed the Edmund Fitzgerald to carry more cargo in 1969, 1971, and 1973. This meant her deck was 3 feet 3.25 inches (0.9970 m) closer to the water than her original design allowed. When she faced 35 feet (11 m) waves, her deck was only 11.5 feet (3.5 m) above the water. Captain Paquette noted this change allowed her to carry 4,000 tons more than she was designed for.

Concerns about the ship's keel welding came up when the USCG increased her cargo limits. Carrying more cargo reduced the ship's ability to float safely. Before these changes, she was a "good riding ship." Afterward, she became slower to respond and recover in waves. Captain McSorley said he didn't like how the ship, which he called a "wiggling thing," behaved.

Maintenance Issues

NTSB investigators thought the ship's past groundings might have caused hidden damage. This damage could have led to structural failure during the storm. Great Lakes ships were usually inspected in drydock only every five years. Some also claimed that Captain McSorley didn't keep up with routine maintenance. An expert who looked at photos of the ship's welds said "the hull was just being held together with patching plates." Questions were also raised about why the USCG didn't find and fix problems with the ship's hatch covers, gaskets, and clamps during inspections before November 1975.

Overconfidence

On the night of November 10, 1975, McSorley said he had never seen bigger seas. Captain Paquette of the Wilfred Sykes agreed, calling it a "monster" sea. The USCG didn't tell all ships to find safe harbor until after 3:35 p.m. on November 10. This was many hours after the weather had worsened.

McSorley was known as a "heavy weather captain" who "beat hell" out of the ship and "very seldom ever hauled up for weather." Paquette thought carelessness caused the sinking. He said McSorley "kept pushing that ship and didn't have enough training in weather forecasting to use common sense." Paquette was never asked to testify during the investigations.

The NTSB said Great Lakes cargo ships could usually avoid severe storms. They suggested setting limits on when ships could operate in bad weather. There were concerns that shipping companies pressured captains to deliver cargo quickly, no matter the weather. At the time, no government agency controlled ship movement in bad weather. The USCG believed only the captain could decide if it was safe to sail.

The USCG Marine Board concluded that sailors on the Great Lakes sometimes became too confident. They thought short trips in calm waters led to an "overly optimistic attitude" about storms. This could lead to putting off repairs or not preparing for bad weather. The Edmund Fitzgerald disaster showed that everyone involved in Great Lakes shipping needed to be more aware of the dangers.

Legal Outcomes

Under maritime law, ships are judged by the laws of their flag country. Since the Edmund Fitzgerald sailed under the U.S. flag, U.S. law applied, even though she sank in Canadian waters. The ship's loss was the most expensive in Great Lakes history, valued at $24 million.

Two widows of crew members sued the ship's owners, Northwestern Mutual, and operators, Oglebay Norton Corporation. Oglebay Norton tried to limit their financial responsibility to $817,920. The company paid money to the families about a year before the official findings were released. The families had to agree to keep the details private. Some believed the USCG's findings were mild to protect the company from expensive lawsuits.

Changes to Shipping Practices

The USCG investigation led to 15 recommendations for Great Lakes shipping. These included rules about cargo limits, how waterproof ships were, rescue abilities, safety equipment, crew training, and information for captains. The NTSB made 19 recommendations for the USCG.

Here are some changes that happened:

- Since 1977, all large ships must use depth finders.

- Since 1980, survival suits are required for every crew member. Life jackets and survival suits must have strobe lights.

- A LORAN-C navigation system was put in place in 1980, later replaced by GPS in the 1990s.

- Emergency Position Indicating Radio Beacons (EPIRBs) are now on all Great Lakes ships. These help locate a ship quickly in a disaster.

- Navigation maps for northeastern Lake Superior were made more accurate.

- NOAA changed how it predicts wave heights.

- The USCG canceled the rule that allowed ships to carry more cargo and sit lower in the water.

- The USCG started annual inspections before November. They check hatch and vent closures and safety equipment.

A deckhand on the Arthur M. Anderson during the storm said the sinking changed everything. He stated, "After that, trust me, when a gale came up we dropped the hook [anchor]." This means ships were more likely to anchor and wait out severe storms.

Memorials

The day after the wreck, Mariners' Church in Detroit rang its bell 29 times. Each ring was for one life lost. The church held this memorial every year until 2006. Then, they started honoring all lives lost on the Great Lakes. After singer Gordon Lightfoot died in 2023, the church bell was rung 29 times for the crew, plus one more time for Lightfoot.

The ship's bell was brought up from the wreck on July 4, 1995. A copy of the bell, with the names of the 29 sailors, was placed back on the wreck. The original bell was given to the Great Lakes Shipwreck Historical Society (GLSHS). It is meant to be a permanent memorial at Whitefish Point, Michigan. The GLSHS is responsible for keeping the bell and cannot sell it or use it for business.

In 1995, there was an issue when a worker cleaned the bell, removing its protective coating. The GLSHS also tried to take the bell on tour in 1996. But relatives of the crew stopped this, saying the bell was being used like a "traveling trophy." As of 2005, the bell is on display at the Great Lakes Shipwreck Museum in Whitefish Point, Michigan.

An anchor from the Edmund Fitzgerald, lost on an earlier trip, was found in the Detroit River. It is now on display at the Dossin Great Lakes Museum in Detroit. This museum also hosts a "Lost Mariners Remembrance" event every November 10. Other items from the ship, like two lifeboats, photos, and models, are in the Steamship Valley Camp museum in Sault Ste. Marie. Every November 10, the Split Rock Lighthouse in Minnesota shines its light in honor of the Edmund Fitzgerald.

In 2015, the Royal Canadian Mint made a special silver coin to remember the Edmund Fitzgerald.

Music and Theater Tributes

Canadian singer-songwriter Gordon Lightfoot wrote the famous song "The Wreck of the Edmund Fitzgerald" for his 1976 album. Lightfoot said he was inspired to write the song after seeing the ship's name misspelled in a magazine. He felt it disrespected the memory of those who died. His song made the sinking one of the most well-known disasters on the Great Lakes.

Lightfoot changed one line in the song for live shows. The original line was:

At 7 p.m. a main hatchway caved in,

He said, "Fellas, it's been good to know ya."

He changed it to "At 7 p.m. it grew dark, it was then."

On May 2, 2023, after Lightfoot died, the Mariners' Church of Detroit rang its bell 30 times. Twenty-nine rings were for the crew, and the 30th was for Lightfoot.

In 1986, Steven Dietz and Eric Peltoniemi wrote a musical called Ten November about the sinking. In 2005, it was remade into a concert version called The Gales of November. It opened on the 30th anniversary of the sinking.

In November 2000, Shelley Russell's play, Holdin' Our Own: The Wreck of the Edmund Fitzgerald, opened. It had a cast of 14 actors.

An American composer, Geoffrey Peterson, wrote a piano concerto called The Edmund Fitzgerald in 2002. It was first performed in November 2005 to mark the 30th anniversary.

Commercial Items

Because the Edmund Fitzgerald is so famous, her image and story are used for many commercial products. A "cottage industry" has grown around the Great Lakes. You can find Christmas ornaments, T-shirts, coffee mugs, and even a special beer called Edmund Fitzgerald Porter. These items help remember the ship and its loss.

See also

In Spanish: SS Edmund Fitzgerald para niños

In Spanish: SS Edmund Fitzgerald para niños

- Graveyard of the Great Lakes

- List of maritime disasters

- List of shipwrecks in the Great Lakes

- List of storms on the Great Lakes

- MV Derbyshire, a British cargo ship lost in 1980 in similar ways

Images for kids

| William L. Dawson |

| W. E. B. Du Bois |

| Harry Belafonte |