Scottish trade in the early modern era facts for kids

Scottish trade in the early modern era looks at how Scotland bought and sold goods from the early 1500s to the mid-1700s. This time is known as the early modern era. It started with the Renaissance (a time of new ideas) and the Reformation (changes in religion). It ended with the last Jacobite risings (attempts to put the old royal family back on the throne) and the start of the Industrial Revolution.

At the start of this period, Scotland was quite a poor country. It had tough land and it was hard to travel around. There wasn't much trade inside Scotland itself. Most towns relied on what they made nearby. International trade was like it had been in the Middle Ages. Scotland mostly sold raw materials and bought fancy goods or things it didn't have.

The early 1500s saw trade grow a bit. But then English invasions in the 1540s caused problems. The late 1500s brought tough times. Prices went up, and there were famines. However, things also became more stable. New ways of making things started to appear. The early 1600s saw trade grow again until the late 1630s. After that, wars and English occupation caused a lot of trouble.

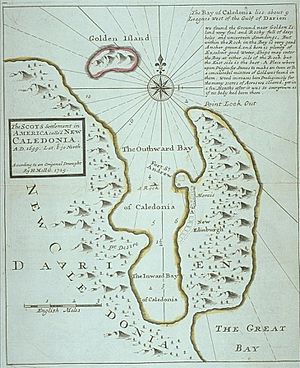

After the Restoration in 1660, trade got better. Scotland traded more with England and the Americas. But there were still problems with taxes on goods. A big plan to start a Scottish colony in Central America, called the Darién scheme, failed badly in the 1690s. After Scotland joined with England in 1707, the cattle trade and coal mining grew even more. Linen cloth became a very important product. Trade with the Americas kept growing. This led to the rich Tobacco Lords in Glasgow. Greenock traded in sugar and rum. Paisley became known for its cloth. New banks like the Bank of Scotland and Royal Bank of Scotland also started. Roads got better too. All these changes helped lead to the Industrial Revolution later in the 1700s.

Contents

How Trade Started in Scotland

A historian named Jenny Wormald once said that calling Scotland a "poor country" was very true. At the start of this time, Scotland had rough land and bad roads. It was hard to move goods around. So, there was little trade between different parts of the country. Most towns and villages depended on what they made themselves. They often had very little extra if times were bad.

Foreign trade was controlled by a few special towns called royal burghs. Smaller towns, called baronial or church burghs, mostly served as local markets. They were also places where craftspeople worked.

From the 1300s, Scottish exports and most imports went through a special trading place called the Staple. For a long time, it was in Bruges, a town in Flanders. In 1508, King James IV moved the Staple to Veere, a small port in Zealand. It stayed there until the late 1600s. Most of Scotland's exports were raw materials. These included wool, coal, and fish. The main imports were luxury items like cloth, wine, and military gear. Scotland also imported raw materials it didn't have, like wood and iron. Important trading partners included France, Scandinavia, and England. England was only the fourth most important partner. It mainly bought salt and coal from Scotland.

Trade in the 1500s

Trade slowly grew in the 1530s. But it suffered badly from English invasions in the 1540s. From the mid-1500s, fewer people in Europe wanted Scottish cloth and wool. So, Scots started selling more of their traditional goods. They increased how much salt, herring, and coal they produced.

The late 1500s were a tough time for the economy. Taxes went up, and money lost its value. For example, in 1582, a pound of silver was worth 640 shillings. By 1601, it was worth 960 shillings. The Scottish pound also became worth less compared to the English pound. Wages went up quickly, but not fast enough to keep up with rising prices. There were also many bad harvests. Almost half the years in the late 1500s saw food shortages. This meant Scotland had to buy a lot of grain from the Baltic Sea region. This area was like Scotland's "emergency food store." Grain came mainly from Poland through the port of Danzig. Later, Königsberg and Riga (shipping Russian grain) and Swedish ports also became important. This trade was so vital that Scottish communities were set up in these ports.

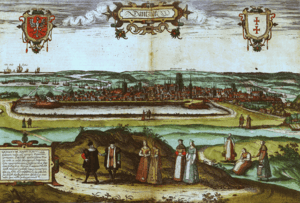

The importance of Scottish towns in foreign trade changed. Haddington, which had been a big trading center, saw its foreign trade almost disappear. Aberdeen's trade stayed steady for most of the century but dropped in the last ten years. Small ports in Fife became more important. Edinburgh's share of trade grew a lot through its port, Leith. In 1480, Edinburgh handled 54% of export money. A century later, it was 75%. This made smaller ports try new types of goods and do more trade along the coast. Overall, foreign trade increased from the 1570s, with Edinburgh getting most of it.

The time when King James VI ruled (1567–1625) was mostly stable. The government didn't know much about how the economy worked. So, they mostly tried to create monopolies, where only one group could trade certain goods. New industries started to appear. Scotland brought in experts from other countries. For example, they tried to get Flemings to teach new cloth-making skills. They also brought a Venetian expert to help make glass. In 1596, the Society of Brewers started in Edinburgh. They began making Scottish beer using English hops. George Bruce used German methods to solve water problems in his coal mine at Culross. Lead mining at Leadhills also grew. Most of the raw lead was sold to other countries.

Trade in the Early 1600s

King James VI became king of England and Ireland in 1603. He tried to join the economies of England and Scotland. But people in both countries didn't trust each other, so it didn't happen. One good thing was that the Borders became peaceful. This stopped the raids and local wars by the Border Reivers. King Charles I (who ruled from 1625–49) also tried to bring the economies closer. He even tried a common fishing plan, but it failed.

Generally, the early 1600s were a time of growing wealth. Edinburgh gained almost complete control over international trade in important goods. The profits went to a small group of rich "merchant princes." Many of them put their money into new businesses. These included coal mining, salt production, and lending money. This good time ended in the 1630s. It was completely stopped by the Bishop's Wars (1639–40) and the Civil Wars (1642–51).

The English invasions in the 1640s greatly affected Scotland's economy. Crops were destroyed, and markets were disrupted. This caused prices to rise very quickly. Under the Commonwealth (when England ruled without a king), Scotland was taxed heavily. But it also gained access to English markets. When the king returned in 1660, high taxes and occupation ended. The border with England was put back, along with its customs duties. Growth slowly returned, but wealth probably didn't reach the levels of the 1630s. Scottish money remained weak and unreliable. No gold coins were made in Edinburgh after 1638. Scotland bought more than it sold, so it had to send out a lot of silver. Most coins used between 1670 and 1707 were not Scottish. This meant Scottish merchants had to change money often. Gifts of money often stated both the amount and the type of currency.

Trade in the Late 1600s

In the late 1600s, the special trading place at Veere was often ignored. Ships carrying coal and iron from the Forth ports went straight to big ports like Amsterdam and Rotterdam. Imports started to include more luxury goods. These included beer, spices, wine, pictures, iron, salt, soap, and feather beds.

The special right of royal burghs to control foreign trade partly ended in 1672. They kept control over old luxury goods like wines, silk, and dyes. But trade in important goods like salt, coal, corn, hides, and goods from the Americas was opened up. The English Navigation Acts made it hard for Scots to trade with England's growing colonies. But Scots often found ways around these rules.

Glasgow became a very important trading city. It started trading with the American colonies. It imported sugar from the West Indies and tobacco from Virginia and Maryland. It also got deerskin through trade with Native Americans. Scottish exports to America included linen, wool goods, coal, and grindstones. English taxes on salt and cattle were harder to avoid. These taxes likely limited Scotland's economy more. Scottish attempts to add their own taxes didn't work well. Scotland had few important exports to protect. Attempts by the Privy Council to build luxury industries like cloth mills and soap works also mostly failed.

However, by the end of the century, drovers roads were well-established. These roads stretched from the Highlands down through south-west Scotland to north-east England. Black cattle raised in the Highlands were driven along these roads to be sold in northern England. Some were then driven to Norfolk to get fatter. Finally, they were slaughtered in Smithfield to feed the people of London.

The last ten years of the 1600s saw the good economic times end. The Glorious Revolution in 1689 changed Scotland's relationship with France. Scotland got involved in King William II's wars against Louis XIV. Trade with the Baltic and France dropped from 1689–91. This was due to France protecting its own goods and changes in the Scottish cattle trade. Then came four years of bad harvests (1695, 1696, and 1698-99), known as the "seven ill years."

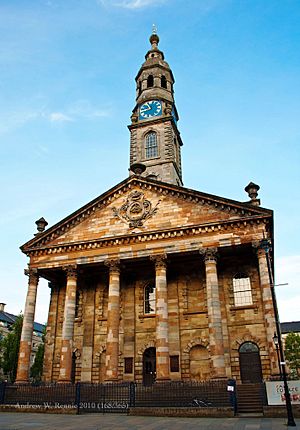

The Scottish Parliament in 1695 made plans to help the bad economy. One plan was to set up the Bank of Scotland. This was Scotland's first company where many people could own shares. It had limited risk for its owners. It also had a monopoly (sole right) to do banking for 21 years. It opened in early 1696 with £10,000 sterling. It worked with banks in London and Amsterdam. It gave loans and printed banknotes. It aimed to help trade, not just the government. It gave loans to government agents just like it gave commercial loans.

The Company of Scotland Trading to Africa and the Indies also got permission to raise money from the public. The Company of Scotland invested in the Darién scheme. This was a big plan by William Paterson, who also started the Bank of England. He wanted to build a colony on the Isthmus of Panama. The idea was to trade with the Far East. The Darién scheme got a lot of support in Scotland. Rich landowners and merchants believed that trade overseas and colonies would make Scotland's economy better.

The rich people in Edinburgh didn't have enough money. So, the company asked ordinary people for money. People responded with great national pride. Even poorer people volunteered to be colonists. However, the English East India Company and the English government were against the idea. The East India Company saw it as a threat to their business. The English government was fighting a war with France (1689-1697). They didn't want to upset Spain, which claimed the land in Panama. So, English investors pulled out of the project.

Back in Edinburgh, the Company raised £400,000 in a few weeks. Three small fleets with 3,000 men eventually sailed for Panama in 1698. The whole plan was a disaster. The colonists were not well-equipped. They faced constant rain and disease. The Spanish attacked them from nearby Cartagena. The English in the West Indies refused to help. The colonists gave up their project in 1700. Only 1,000 people survived, and only one ship made it back to Scotland. The cost of £150,000 put a huge strain on Scotland's money system. It caused a lot of anger against England. But it also showed the problems of having two separate economic policies. This increased the pressure for Scotland and England to fully unite. The Acts of Union of 1707 that created Great Britain were mostly about money matters. Scotland gained access to English markets and colonies. Some Scottish groups got special deals. There were also large payments to make up for Scotland's recent losses. It was a full money union. The Bank of Scotland oversaw the changing of Scottish coins into English sterling.

Trade in the Early 1700s

In the early 1700s, the cattle trade grew a lot. About 30,000 cattle were traded each year in 1700. By the mid-century, this number was perhaps 80,000. Coal mining also kept growing. It went from about 225,000 tons a year in the late 1600s to at least 700,000 tons by 1750.

The biggest change in international trade was the fast growth of the Americas as a market. Glasgow sent cloth, iron farm tools, glass, and leather goods to the colonies. At first, Glasgow used hired ships. But by 1736, it had 67 of its own ships. A third of these traded with the New World. Glasgow became the main center for the tobacco trade. It re-exported tobacco, especially to France. The merchants who dealt in this profitable business became the rich tobacco lords. They controlled Glasgow for most of the century.

Other towns also benefited. Greenock made its port bigger in 1710. It sent its first ship to the Americas in 1719. Soon, it was a major player in importing sugar and rum.

In 1700, most cloth was made at home. Rough plaids were produced. But the most important type of manufacturing was linen cloth. This was especially true in the Lowlands. Some people even said Scottish flax was better than Dutch flax. Scottish members of parliament stopped a plan to put a tax on linen exports. From 1727, linen received government money of £2,750 a year for six years. This led to a big increase in trade. This money came from the Board of Trustees for Fisheries and Manufactures in Scotland. This Board used money set aside when Scotland and England united. It gave £6,000 a year to encourage industry, especially linen and fishing.

Paisley started using Dutch methods and became a big center for linen production. Glasgow made linen for export. This trade doubled between 1725 and 1738. Soon, "manufacturers" managed the trade. They gave flax to spinners. Then they bought back the yarn and gave it to weavers. They bought the finished cloth and sold it again. Overall, output tripled between 1728 and 1750. The British Linen Company also started giving cash loans in 1746. This helped production even more.

Besides the British Linen Company getting into banking, there were other banking changes. The Bank of Scotland was thought to support the Jacobites. So, a rival bank, the Royal Bank of Scotland, was started in 1727. Local banks began to appear in towns like Glasgow and Ayr. These included the Ship Bank (1749) and the Arms Bank (1750) in Glasgow. Later came the Thistle Bank (1761) and the Ayr Bank (1769). These banks provided money for businesses and for improving roads and trade. This helped create the right conditions for the Industrial Revolution, which sped up in the second half of the century.

More to Explore