Border reivers facts for kids

Border reivers were groups of people who raided along the Anglo-Scottish border from the late 1200s to the early 1600s. They were from both Scottish and English families. These raiders stole from anyone in the border country, no matter their nationality. They were most active during the last 100 years of their time, when the House of Stuart ruled Scotland and the House of Tudor ruled England.

Contents

Why They Became Reivers

Scotland and England often fought wars during the Middle Ages. These wars made life very hard for people living near the Borders. Even when there was no war, things were tense. The kings and queens in both countries often had weak control over these distant areas.

Because survival was so difficult, families and communities banded together. They tried to make their lives better by taking things from their neighbors, who were also just trying to survive. Relying on the king or the law often made people targets instead of keeping them safe.

Other reasons also led to this raiding lifestyle. In some parts of the English Borders, land was divided equally among all sons when a father died. This meant that each son might not get enough land to live on. Also, much of the Border region is hilly or open moorland. This land is not good for growing crops but is perfect for raising animals. Livestock like cattle and horses were easy to steal and drive away by reivers who knew the land well. The raiders also took valuable household items and sometimes captured people to demand money for their return.

The governments of England and Scotland sometimes allowed or even encouraged these fierce families. This was because the reivers acted as a first line of defense against invasions. But when their lawlessness became too much, the authorities would punish them very harshly.

The word "reive" means "raid." It comes from old words meaning "to rob or plunder." The term "border reiver" was first used by Sir Walter Scott in his book Minstrelsy of the Scottish Border.

What Reivers Were Like

Reivers were from both England and Scotland. They raided both sides of the border fairly, as long as the people they attacked had no strong protectors or were not related to their own family. Their raids usually happened within a day's ride of the border, but sometimes they went further. English raiders reached the edge of Edinburgh, and Scottish raids went as far south as Lancashire and Yorkshire.

The main raiding season was in the early winter. The nights were longest then, and the cattle and horses were fat from summer grazing. A raid could involve a few dozen riders or even large groups of up to three thousand.

When raiding, or "riding" as they called it, reivers rode light horses or ponies. These horses were known for being able to cross the boggy lands easily. Reivers first wore simple shepherd's plaids. Later, they wore light armor like "jacks of plate" (sleeveless jackets with small steel plates sewn in) and metal helmets. This is why they were nicknamed the "steel bonnets." They carried light lances, small shields, and sometimes longbows or light crossbows. Later, they also used pistols. They always carried swords and dirks (small daggers).

Reivers as Soldiers

Border reivers were sometimes hired as soldiers because they were skilled light cavalry. Reivers often served in English or Scottish armies in places like the Low Countries and Ireland. They sometimes did this to avoid punishment for their own actions. Reivers fought as soldiers in important battles like Flodden and Solway Moss.

Queen Elizabeth I once met a famous reiver, the Bold Buccleugh. She reportedly said that with ten thousand such men, James VI could challenge any king in Europe.

However, these borderers were hard to control in larger armies. They often changed their nationality depending on what suited them best. Many had relatives on both sides of the Scottish-English conflicts, even though marrying across the border was against the law. They could cause trouble in army camps, seeing fellow soldiers as targets for stealing. They were more loyal to their own families (clans) than to nations, so their commitment was often uncertain. At battles like Ancrum Moor in Scotland in 1545, borderers even switched sides during the fight to gain favor with the likely winners. At the Battle of Pinkie Cleugh in 1547, someone saw Scottish and English borderers chatting. Then, they put on a show of fighting hard once they knew they were being watched.

Homes and Fortifications

People living in the Borders had to be ready for danger at all times. To protect themselves, they built strong tower houses.

During the worst times of war, people could only build simple huts made of turf. Losing these would not be a big deal. But when times were a bit better, they built houses designed for defense as much as for living. The bastle house was a strong two-story building. The ground floor was used to keep valuable animals and horses safe. The upper floor was where the people lived. You could often only reach it by an outside ladder, which was pulled up at night or if danger was near. The stone walls were very thick, about 3 feet (1 meter), and the roof was made of slate or stone tiles. Only narrow slits allowed light and air. These homes could not be easily burned down. While they could be captured, for example, by smoking out the defenders, they usually weren't worth the effort.

Peel towers were usually three-story buildings. They were built specifically for defense by authorities or important clan leaders. Smailholm Tower is one of many peel towers still standing. Like bastle houses, they were built very strongly for protection. If needed, they could be left empty with smoldering turf inside to prevent enemies from destroying them with gunpowder.

Peel towers and bastle houses often had a stone wall around them called a barmkin. Inside this wall, cattle and other animals were kept overnight for safety.

Rules and Justice

A special set of rules, called March law or Border law, developed in the region. Under this law, if someone was raided, they had the right to go on a counter-raid within six days to get their goods back. This was called a "hot trod." They had to make a lot of noise with "hound and horne, hew and cry" and carry a burning piece of turf on a spear. This showed everyone their purpose and made sure they weren't mistaken for unlawful raiders. They might use a special dog called a "sleuth hound" to follow the raiders' tracks. Anyone who met this "hot trod" had to join in and help, or they would be seen as helping the raiders. A "cold trod," which happened after six days, needed official permission.

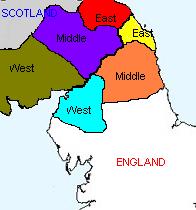

Both sides of the border were divided into areas called Marches. Each March was led by a march warden. These wardens were in charge of patrols, watches, and soldiers to stop raids from the other kingdom. Sometimes, wardens would lead their own "warden roades" to get back stolen goods and send a message to raiders.

The march wardens also tried to keep things fair. Wardens from both kingdoms would meet at certain times along the border. These meetings, called "Days of Truce," were like big fairs with entertainment and socializing. For reivers, it was a chance to meet relatives or friends who were usually separated by the border. Sometimes, violence even broke out at these truce days.

However, march wardens were often not very good at keeping law and order. Scottish wardens were usually borderers themselves and sometimes involved in raiding. They often favored their own families, which caused problems with other Scottish border families. Many English officers came from southern England and often couldn't get the local people or their own soldiers to respect them. Some local officers became known for being corrupt, just like the worst Scottish wardens.

By the time Elizabeth I of England died, things were so bad that the English government thought about rebuilding Hadrian's Wall. When Elizabeth died, there was a very violent period of raiding known as "Ill Week." This happened because people believed that the laws were paused between the death of a ruler and the start of the next one. When James VI of Scotland became James I of England, he took strong action against the reivers. He ended border law and even changed the name "Borders" to "Middle Shires," giving strict justice to reivers.

Laws were passed to stop the raiding and bring peace to the border region. These laws aimed to end the old conflicts between England and Scotland and prevent future problems. They also made it easier to bring people to justice if they committed crimes across the border. Over many years, these laws were updated and continued to help control the lawlessness.

Border Families and Clans

Many terms describe the Border families, like "Riding Surnames" and "Graynes." This is similar to the Highland Clans and their smaller groups called septs. For example, the Clan Donald and Clan MacDonald of Sleat are like the Scotts of Buccleuch and the Scotts of Harden. Both Border Graynes and Highland septs had a male leader (chief) and lived in areas where most of their relatives lived. Border families also had customs like the Gaels, such as having a guardian when a young heir became chief, and making loyalty agreements.

In a Scottish law from 1587, there's a description of the "chiefs of all clans... living in the highlands or borders." This shows that the words 'clan' and 'chief' were used for both Highland and Lowland families. The law then lists the different Border clans. Later, in 1680, a lawyer named Sir George MacKenzie said that "chief" means the head of a family, and in the Irish (Gaelic), the chief is called the "head of the clan." So, the words chief or head, and clan or family, can be used interchangeably. The idea that Highlanders are called clans and Lowlanders are called families became popular in the 1800s.

Border Family Names (1587)

In 1587, the Parliament of Scotland passed a law to bring order to the "disorderly subjects" living in the Borders, Highlands, and Islands. This law included a list of family names from both the Borders and Highlands. The Borders part listed 17 'clans' with a Chief and their areas:

Middle March

- Elliot, Armstrong, Nixon, Crozier

West March

- Scott, Bates, Little, Thompson, Glendenning, Irvine, Bell, Carruthers, Graham, Johnstone, Jardine, Moffat, and Latimer.

Some of these Border Clans, like Elliot, Carruthers, Scott, Irvine, Graham, Johnstone, Jardine, and Moffat, are officially recognized as Scottish Clans today. Others, like Armstrong, Little, and Bell, are known as clans but don't have a recognized chief. Some, like Clan Blackadder, died out or lost their lands.

Famous riding surnames listed by George MacDonald Fraser in The Steel Bonnets (1989) include:

East March

Middle March

- Scotland: Burns, Kerr, Young, Pringle, Davison, Gilchrist, Tait of East Teviotdale. Scott, Oliver, Turnbull, Rutherford of West Teviotdale. Armstrong, Croser, Elliot, Nixon, Douglas, Laidlaw, Routledge, Turner, Henderson of Liddesdale.

- England: Anderson, Potts, Reed, Hall, Hedley of Redesdale. Charlton, Robson, Dodd, Dodds, Milburn, Yarrow, Stapleton of Tynedale. Also Fenwick, Ogle, Heron, Witherington, Medford (later Mitford), Collingwood, Carnaby, Shaftoe, Ridley, Stokoe, Stamper, Wilkinson, Hunter, Huntley, Thompson, Jamieson.

West March

- Scotland: Bell, Irvine, Johnstone, Maxwell, Carlisle, Beattie, Little, Carruthers, Glendenning, Routledge, Moffat.

- England: Graham, Hetherington, Musgrave, Storey, Lowther, Curwen, Salkeld, Dacre, Harden, Hodgson, Routledge, Tailor, Noble.

Relationships between Border clans could be uneasy alliances or deadly fights. It didn't take much to start a fight; a simple argument or misuse of power was enough. These fights could last for years until they were stopped by an invasion or when new fights caused alliances to change. The border became unstable if families from opposite sides were fighting. These feuds also gave excuses for very violent raids.

Reivers did not wear special family patterns (tartans). The tradition of family tartans started much later, in the 1800s, inspired by the books of Sir Walter Scott. Reivers usually wore a "jack of plate" (armor), steel bonnets (helmets), and riding boots.

In Books and Stories

Writers like Sir Walter Scott made the reivers seem romantic in his book Minstrelsy of the Scottish Border. He also used the term Moss-trooper, which referred to similar groups in the 1600s. Scott himself was from the Borders and wrote down stories that had been passed down through songs and tales.

The English poet William Wordsworth wrote a play called The Borderers which features border reivers.

Stories about famous reivers like Kinmont Willie Armstrong were often told in folk songs called Border ballads. There are also local legends, like the "Dish of Spurs." This dish would be served to a Border chief to remind him that the food was gone and it was time to raid again. Scottish author Nigel Tranter also wrote about these themes in his historical novels. Scottish Border poet Will H. Ogilvie wrote several poems about the reivers. The book The Steel Bonnets (1971) by George MacDonald Fraser describes life in the Anglo-Scottish border areas during the reivers' most active time.

What Happened Next

The names of the Reiver families are still common among people living in the Scottish Borders, Northumbria, and Cumbria today. These families, especially the large or powerful ones, left a strong sense of local pride on both sides of the Border. Newspapers sometimes describe local cross-border rugby games as "re-runs of the bloody Battle of Otterburn." Despite this, many people have moved across the border since the reivers were stopped. Families who were once Scottish now identify as English, and vice versa.

Hawick in Scotland holds an annual Reivers' festival. The town of Duns also has a summer festival led by a "Reiver" and "Reiver's Lass," young people chosen from the town.

Borderers, especially those sent away by James VI of Scotland, took part in the plantation of Ulster in Ireland. They became the people known as Ulster-Scots (or Scotch-Irish in America). Descendants of reivers can be found throughout Ulster with names like Elliot, Armstrong, Bell, and Turnbull.

Border family names are also found in areas of Scotch-Irish settlement in the United States, especially in the Appalachian region. Historian David Hackett Fischer showed how the Anglo-Scottish border culture became part of the United States. Author George MacDonald Fraser even noted Border traits and names among famous people in American history, like Presidents Lyndon B. Johnson and Richard Nixon. It's also interesting that in 1969, a descendant of the Borderers, Neil Armstrong, was the first person to walk on the moon. In 1972, Armstrong was given special honors in Langholm, Scotland, the home of his ancestors.

The artist Gordon Young created a public artwork in Carlisle called Cursing Stone and Reiver Pavement. It refers to a curse made by an archbishop in 1525. Names of Reiver families are set into the paving of a walkway that connects Tullie House Museum to Carlisle Castle. Part of the old curse is displayed on a large stone.

See also

- Debatable Lands

- History of Northumberland

- The Borderers (television series)