Steamboats of the upper Columbia and Kootenay Rivers facts for kids

From 1886 to 1920, steamboats were a common sight on the upper parts of the Columbia and Kootenay rivers. These rivers are found in the Rocky Mountain Trench in western North America. Steamboat travel became possible because of how the rivers flowed and because new railways were built across the area.

Contents

- Rivers and Railways: How Steamboats Started

- Early Steamboat Adventures

- Making River Travel Easier

- The Baillie-Grohman Canal

- The Upper Columbia Navigation and Tramway Company

- Steamboats on the Upper Kootenay River

- The Dangerous Jennings Canyon

- The End of Steamboat Travel on the Upper Kootenay

- Later Steamboat Operations on the Upper Columbia

- The Last Steamboat Runs

- Finding Old Steamboat Wrecks

- List of Steamboats

Rivers and Railways: How Steamboats Started

The Columbia and Kootenay Rivers

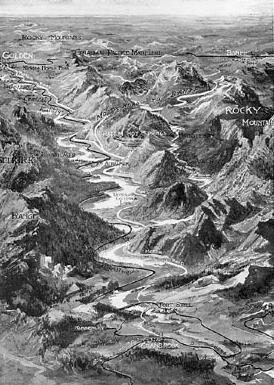

The Columbia River starts at Columbia Lake. It flows north through the Columbia Valley to Windermere Lake and then to Golden. The Kootenay River flows south from the Rocky Mountains. It then turns west into the Rocky Mountain Trench. It gets very close to Columbia Lake, about 1.6 kilometers away, at a place called Canal Flats. A shipping canal was built there in 1889. The Kootenay then flows south, crosses into the USA, and turns north back into Canada. It enters Kootenay Lake near Creston.

The upper Columbia and Kootenay rivers were quite different. The Columbia from Columbia Lake to Golden was shallow and slow. It had many twists and turns. Its elevation only dropped about 15 meters. From Golden, the Columbia flows north to Donald. Then it sharply turns south at the Big Bend. It continues south past Revelstoke and Arrowhead. There, it widens into the Arrow Lakes. Before dams were built, the Big Bend had many rapids. These rapids made it impossible for steamboats to travel upstream from the Arrow Lakes.

The Kootenay River, before the Libby Dam was built, flowed much faster than the Columbia. It went through Jennings Canyon, a very dangerous area with fast-moving water. This was on its way to Jennings and Libby, Montana. Larger steamboats could operate on the upper Kootenay than on the upper Columbia. The Kootenay River flows into Idaho. Then it turns north and flows back into Canada. Near Creston, the Kootenay River enters Kootenay Lake. Steamboats could travel up the lower Kootenay to the railhead at Bonners Ferry, Idaho. However, rapids and falls on the Kootenay blocked boats between Bonner's Ferry and Libby.

Building Railways for Steamboat Travel

Building railways in Canada and the United States helped steamboat travel in the Rocky Mountain Trench. There were two main railway stops: Golden, BC, and Jennings, Montana. At Golden, the Canadian Pacific Railway (CPR) line ran south along the Columbia. Then it turned east to follow the Kicking Horse River. It crossed the Continental Divide at Kicking Horse Pass. From there, it went past Banff and east to Calgary. Jennings was reached by the Great Northern Railway. This line was built across the northern United States by James J. Hill.

Between these two railway stops, the Rocky Mountain Trench stretched for about 480 kilometers. Most of this area could be reached by steamboats. Canal Flats was almost in the middle. It was just south of Columbia Lake, about 200 kilometers upstream from Golden.

Early Steamboat Adventures

The First Steamboats: Duchess and Clive

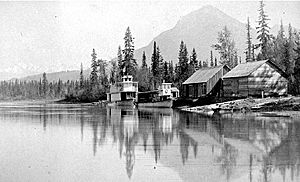

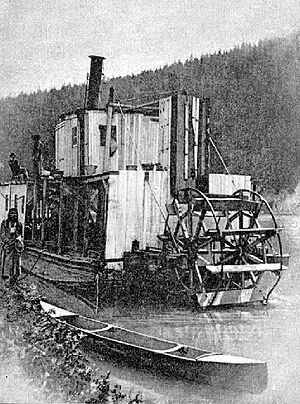

In 1886, a man named Frank P. Armstrong built a steamboat. He used old planks and wood from a sawmill. He called it the Duchess. It was launched in 1886 at Golden. Some early passengers said it looked "somewhat decrepit" (meaning old and worn out). Armstrong himself later agreed it was "a pretty crude steamboat."

In 1886, there was a supposed "uprising" among the First Nations people down the Kootenay River. A group of North-West Mounted Police, led by Major Samuel Benfield Steele, was sent to Golden. Their orders were to go to the Kootenay to stop the uprising. Steele decided to hire Armstrong and the Duchess to carry his soldiers. This turned out to be a mistake. Once the horses' food, ammunition, uniforms, and other supplies were loaded, the Duchess tipped over and sank!

After this problem, Steele decided to hire the only other steam boat on the upper Columbia, the Clive. The Clive, like the Duchess, was made from old and used parts. It was even worse. Once Steele loaded his soldiers' equipment onto the Clive, that boat also sank! Steele and his troops ended up riding about 240 kilometers south to Galbraith's Landing. This trip took about a month. When they arrived, the soldiers set up a camp. This camp later became the town of Fort Steele. By then, the "uprising" was already over.

Better Steamboats Arrive

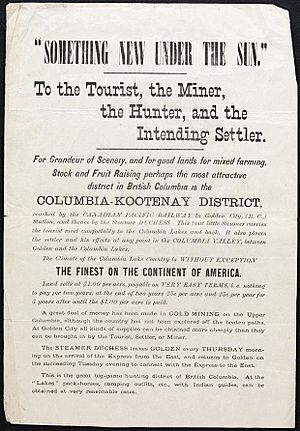

Armstrong was eventually able to get the first Duchess out of the river. He used this odd-looking boat to earn enough money in 1887 to build a new sternwheeler. This new boat was also called Duchess. Armstrong hired a skilled shipbuilder, Alexander Watson, from Victoria. The new steamer was small but well-designed. It looked like a proper steamboat, not an old floating barn.

Someone arranged to print handbills (flyers) to promote the new Duchess. One side had a picture of the new Duchess. The other side explained the company's plan. They wanted to attract tourists, miners, hunters, and new settlers. They said the Duchess was the best way to get around the Columbia Valley.

The flyer also praised the Columbia Valley's climate. It called it "WITHOUT EXCEPTION THE FINEST ON THE CONTINENT OF AMERICA." Land was available for $1.00 per acre, payable over five years. Gold mining was said to be good, with hints of more gold to be found. The flyer said "the country has not been explored off the beaten paths." All kinds of supplies were cheaper at Golden City. Finally, the flyer announced the schedule for the new Duchess:

The STEAMER DUCHESS leaves GOLDEN every THURSDAY morning on the arrival of the Express from the East, and returns to Golden on the succeeding Tuesday evening to connect with the express to the East.

This is the great big-game hunting district of British Columbia. At the "Lakes" pack-horses, camping outfits, etc., with Indian guides, can be arranged at very reasonable rates.

Armstrong also built a second steamer, the Marion. It was smaller than the second Duchess. But it only needed 15 centimeters of water to run. This was a big help in the often shallow parts of the Columbia River above Golden. Armstrong said that "the river's bottom was often very close to the river's top."

Making River Travel Easier

Clearing the River

The upper Columbia River had many "snags." These were sunken logs stuck in the riverbed. They were a big problem for boats. For example, it took the Clive 23 days to travel 160 kilometers up to Windermere Lake. Many snags caused this delay.

To remove snags, a special boat called a "snag boat" was used. It had a large crane and strong winches to pull the logs out. (You can still see examples like the Samson V at New Westminster, BC and the W.T. Preston at Anacortes, Washington.) In 1892, the government put a snag boat, the Muskrat, on the upper river. This greatly improved river travel.

Another problem on the upper Columbia was the many sandbars. These were used by salmon for spawning. A clam shell dredge was used to dig out the river bottom and make the sandbars deeper. However, this probably harmed the salmon spawning grounds.

Carrying the Mail by Steamboat

On May 1, 1888, Armstrong got a contract from the Canadian Post Office. He was to carry mail on the 320-kilometer route from Golden to Cranbrook. Armstrong carried the mail twice a week on the Duchess. When the water was low, he used the Marion. They went up to Columbia Lake. From there, the mail was transferred to a stagecoach line. This line took the mail across Canal Flats and down the Kootenay River valley to Grohman, Fort Steele, and Cranbrook.

The contract was renewed from 1889 to 1892. When the river was too low or frozen, Armstrong had the mail carried overland by wagon road. The mail contracts were renewed again from 1893 to 1897. The mail then ran from Golden to the St. Eugene Mission in the Kootenay Valley. These mail contracts were very important for Captain Armstrong and his Upper Columbia Company.

People living along the upper Columbia would wave down the mail steamer to send letters or freight. The captain would steer the front of the boat into the riverbank. The sternwheel would keep the boat in place. Mail would be picked up, or freight loaded, fees collected, and then the boat would continue. In April 1897, the Upper Columbia Company lost the mail contract. This meant customers would still flag down the steamer for letters, but the company wasn't paid to carry them.

The Company's Own "Postage Stamps"

The company didn't want to upset potential freight customers by refusing letters. But they also didn't want to carry mail for free. So, the company's business manager, C.H. Parson, had the company print its own "postage stamps." They printed 1,000 "stamps" with the letters "U.C." (for Upper Columbia Company) and a value of 5 cents. They also printed 1,000 more "labels" with just the letters "U.C."

An ordinary letter cost 3 cents to send back then. So, the Upper Columbia Company's "stamps" were more expensive. The idea was probably to discourage people from using the steamer for mail. Maybe they also hoped to make a little extra money. It's not clear exactly how these stamps and labels were used. But some did go through the official Canadian mail with regular postage stamps added. Original envelopes (called "covers") with these Upper Columbia Company stamps or labels are very rare. Stamp collectors highly value them.

Fake covers have appeared, made to trick collectors. Knowing the history of the Upper Columbia Company helps tell if a cover is real or fake.

The Baillie-Grohman Canal

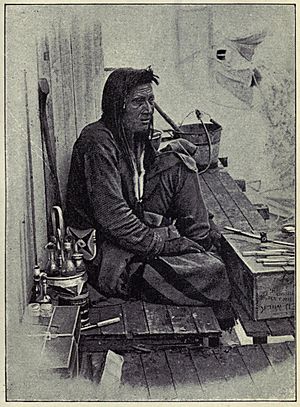

In the early 1880s, a rich European adventurer named William Adolf Baillie-Grohman traveled to the Kootenay Region. He became very interested in developing an area called Kootenay Flats. This was far down the Kootenay River, near the southern end of Kootenay Lake, close to the town of Creston.

The problem for Baillie-Grohman was that the Kootenay River kept flooding Kootenay Flats. He thought the flooding could be reduced by sending some of the Kootenay River's water into the Columbia River through Canal Flats. However, this would have increased the water flow in the Columbia River, especially near Golden and Donald. If his plan had been carried out, it could have flooded the newly built railway and other parts of the Columbia Valley.

The government said no to his plan to divert the river. But Baillie-Grohman was able to get ownership of large areas of land in the Kootenay region. He had to promise to do certain things to help the economy. This included building a shipping canal and a lock. The lock was needed because the Kootenay River was about 3.4 meters higher than Columbia Lake.

The Baillie-Grohman canal was used only three times by steam-powered boats. In 1893, Armstrong built the Gwendoline on the Kootenay River. He took the boat through the canal north to the shipyard at Golden to finish building it. In late May 1894, Armstrong took the completed Gwendoline back to the Kootenay River, using the canal again.

The canal was not used again until 1902. That year, Armstrong brought the North Star north from the Kootenay to the Columbia. This trip was only possible because the lock at the canal was broken. This made the canal unusable for its original purpose.

About 8 kilometers north of Columbia Lake, the river widened into another lake. It was first called Mud Lake, but later changed to Adela Lake. The 8-kilometer stretch between Adela Lake and Columbia Lake was shallow. It was hard to navigate even for Armstrong's very shallow boats.

Armstrong's solution was to start a new company: the Upper Columbia Navigation and Tramway Company ("UCN&TC"). The company's rules said it had to build two tramways to improve transport. Armstrong was the manager, and T.B.H. Cochrane was the president.

The company built two tramways that used horses or mules. One ran from the CPR station at Golden to a point 3.2 kilometers south. This was where the Kicking Horse River flowed into the Columbia. The company's steamboat dock was located there.

The second tramway was further upriver. It was 8 kilometers long. It ran from Adela Lake, BC, south to Columbia Lake. Tramways were like small railways, but the cars were pulled by horses and were much smaller than train cars. The company had steamers on Columbia Lake and the Kootenay River. But they did not use the Grohman Canal. Instead, they carried goods over Canal Flats. The canal was only used twice by steamboats in its entire history.

With the tramways, the 480-kilometer journey from the Golden railway station to Jennings, Montana, worked like this: Freight would go on the tramway to the steamboat dock at Golden. Then it was loaded onto a steamer. The steamer went upriver to the south end of Windermere Lake. The freight was then carried around Mud (or Adlin) Lake to Columbia Lake. Once at Columbia Lake, the cargo was loaded onto another steamboat, the Pert. It went to the south end of Columbia Lake. There, it was unloaded again, carried across Canal Flats, and loaded onto another steamer on the Kootenay River. This boat then traveled down to Jennings, going through Jennings Canyon.

Steamboats on the Upper Kootenay River

Mining and New Boats

Mining was growing in the upper Kootenay valley in the early 1890s. Miners needed a way to get to the area and transport their supplies. The ore dug from the mountains also had to be moved out. In the early 1890s, there were no railways nearby. Without transport to a smelter (a place to process ore), the mined ore was worthless. The closest railway was the Great Northern Railway at Jennings, Montana. This was over 160 kilometers from the main mining areas at Kimberley and Moyie Lake. Moving the ore by land was impossible. It could only be moved by boat on the Kootenay River.

Because of this, Walter Jones and Captain Harry S. DePuy started the Upper Kootenay Navigation Company ("UKNC"). In the winter of 1891-1892, they built a small sternwheeler called the Annerly at Jennings. When the ice melted in the spring of 1893, DePuy and Jones were able to take the Annerly about 210 kilometers upriver to Quick Ranch. This was about 24 kilometers south of Fort Steele, BC. There, the Annerly picked up passengers and loaded 50 short tons of ore. Returning to Jennings, Jones and DePuy earned enough money to hire James D. Miller. He was a very experienced steamboat captain in the Pacific Northwest. He managed the Annerly for the rest of the 1893 season.

Growing Competition on the Kootenay

Armstrong also wanted to profit from the demand for shipping. So, he moved south from the Columbia to the Kootenay. He built the small sternwheeler Gwendoline at Hansen's Landing. This was about 19 kilometers north of the town of Wasa. Armstrong's plan was to move the ore north across Canal Flats. Then it would go down the Columbia to the CPR railway at Golden. As mentioned earlier, Armstrong took the Gwendoline through the Baillie-Grohman canal in the fall of 1893. He finished fitting her out at Golden. Then he returned through the canal in the spring of 1894.

In March 1896, Miller started working with Armstrong's Upper Columbia Navig. & Tramway Co. to run the Annerly. In 1896, Armstrong and Miller built the Ruth at Libby, Montana. Launched on April 22, 1896, the Ruth was 275 tons. It was the largest steamer to operate on the upper Kootenay River so far. Like the second Duchess, the Ruth was designed and built by a professional shipbuilder, Louis Pacquet, from Portland, Oregon. The Ruth made trips downriver to Jennings. The smaller Gwendoline traveled upriver with goods to Canal Flats and the portage tramway.

Armstrong, Miller, and Wardner, with their new boat Ruth, created strong competition for Jones and DePuy's UKNC. Their only boat was the barely adequate Annerly. Large bags of ore were piling up at Hansen's Landing from the mines. All of it needed transport. The competing companies agreed to share the business on the Kootenay River. To earn their share, DePuy and Jones built the Rustler (125 tons) at Jennings in 1896. The Rustler reached Hansen's Landing in June 1896 on its trip up from Jennings.

Another competitor was Captain Tom Powers. He traded 15 cayuse horses for the machinery to build a small steamer near Fort Steele. He called it the Fool Hen. The machinery was too big for the Fool Hen, and there was no room for freight. Powers used old wooden packing cases from Libby merchants to make his paddlewheel buckets. So, as the steamer moved, the merchants' names spun around on the wheel. Soon after the Fool Hen was finished, Powers removed its engines. He put them into a new steamer, the Libby. This time, the engines were too small for the boat's body. The Libby was only used sometimes in 1894 and 1895.

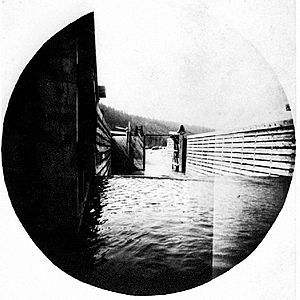

The Dangerous Jennings Canyon

In the United States, the Kootenay River, before the Libby Dam, flowed through Jennings Canyon to the town of Jennings, Montana. Jennings is almost gone now, but it was near Libby, Montana. Above Jennings, the Kootenay River became very narrow in Jennings Canyon. This was a big danger for any boat. A particularly risky part was called the Elbow. Professor Lyman described Jennings Canyon as "a strip of water, foaming-white, downhill almost as on a steep roof, hardly wider than steamboat."

No insurance company would insure steamboats and their cargo going through Jennings Canyon. Captain Armstrong once convinced an agent from San Francisco to consider giving a price for insurance. The agent decided to see the route himself. He went on board with Armstrong as the captain's boat sped through the canyon. At the end of the trip, the agent's price for insurance was one-quarter of the cargo's value! Faced with this high price, Armstrong decided not to get insurance.

The huge profits that could be made seemed to be worth the risk. Together, two steamers could earn $2,000 in total income per day. That was a lot of money in 1897. For comparison, the sternwheeler J.D. Farrell (1897) cost $20,000 to build in 1897. So, in just ten days of operation, a whole steamboat could be paid for.

Only seven steamboats ever went through Jennings Canyon: Annerly, Gwendoline, Libby, Rustler, Ruth, J.D. Farrell, and North Star (1897). Of these, only Annerly and Libby were not wrecked in the canyon. Armstrong and Miller tried to get the U.S. Government to pay for clearing some rocks and obstacles in Jennings Canyon. Without government help, they hired crews themselves to do the work over two winters. But the results were not very helpful.

The Rustler was the first steamboat lost in Jennings Canyon. In the summer of 1896, after only six weeks of use, the Rustler got caught in a swirling current in the canyon. It spun around and crashed into rocks. It was damaged beyond repair. This left DePuy and Jones with only one boat, the "nasty little Annerly." DePuy and Jones could not stay in business after losing the Rustler. They had to sell their facilities at Jennings and the Annerly to Armstrong, Miller, and Wardner.

With their main competitors gone, Armstrong, Miller, and Wardner started their own company. It was called the International Transportation Company ("ITC"). They started it on April 5, 1897, in Washington state. They used parts salvaged from the Rustler to build the North Star. They launched this new boat at Jennings on May 28, 1897.

The wreck of the Gwendoline and Ruth on May 7, 1897, was perhaps the most dramatic. With no insurance, both the Ruth and Gwendoline were going through Jennings Canyon. The Ruth, with Captain Sanborn, was about an hour ahead of the Gwendoline, with Armstrong himself. Both steamers were heavily loaded. A 26-car train was waiting at Jennings for their cargo. The Ruth reached the Elbow, lost control, and stopped, blocking the main channel. The Gwendoline came through at high speed and could not avoid crashing into the Ruth. No one was killed. However, the Ruth was completely destroyed. The Gwendoline was badly damaged, and the cargo on both boats was lost. The North Star was almost finished when this disaster happened. Once it was launched, Armstrong was able to make 21 round trips on the Kootenay. Then low water forced him to stop on September 3, 1897.

The End of Steamboat Travel on the Upper Kootenay

In the summer of 1897, a new competitor appeared for Armstrong, Miller, and Wardell. With money from John D. Farrell, steamboat captain M.L. McCormack started the Kootenai River Transportation Company on August 16, 1897. They began building a new steamer, the J.D. Farrell. It was launched on November 8, 1897, and finished over the winter. Meanwhile, in January 1898, both Armstrong and Wardner sold their shares in the International Trading Company. They went north to Alaska to join the Klondike Gold Rush. Armstrong decided to try his luck as a steamboat captain on the Stikine River. This river was promoted as the "All-Canadian" route to the Yukon River gold fields.

The J.D. Farrell was the largest steamboat ever built on either the upper Kootenay or Columbia Rivers. It had luxuries like bathrooms, electric lights, and steam heat. It reached Fort Steele on April 28, 1898, on its first trip up the Kootenay. This fine steamer was built to last ten years. But it only ran for one season on the Kootenay. On June 8, 1898, Captain McCormack was taking the J.D. Farrell south through Jennings Canyon. A very strong headwind blew it off course into a rock, making a hole in the back. McCormack managed to get the steamer to shallow water before it sank up to the wheelhouse. Its owners were able to raise the J.D. Farrell and make a few more trips that season.

By October 1898, enough railway lines were finished along the upper Kootenay. This made steamboat travel no longer a good way to transport goods. In particular, the Crow's Nest Railway was completed on October 6, 1898. Also, new smelters were built in the Kootenay region, especially at Trail, BC. This allowed ore to be sent to smelters by rail, completely avoiding Jennings.

The remaining upper Kootenay boats, North Star, J.D. Farrell, and Gwendoline, were stored at Jennings. (The Annerly had already been taken apart.) The J.D. Farrell and North Star were tied up for almost three years at Jennings. Then they found work helping to build a railway line to Fernie, BC. The J.D. Farrell was later taken apart. Its engines and machinery were used on another steamer. (This was a common practice.) The North Star was sold back to Captain Armstrong when he returned from his Yukon adventure. On June 4, 1902, he took her north to the Columbia River. This was his famous trip through the old Baillie-Grohman canal, helped by dynamite. With the North Star gone, steamboating on the upper Kootenay ended for good.

The Gwendoline's fate was unique. When Armstrong and Wardner left ITC for the north, James D. Miller was in charge of the ITC boats. He had the idea of moving the Gwendoline to the lower Kootenay River by rail. He hoped it could make money there. In June 1899, he had the boat loaded onto three flat cars. Then disaster struck. The boat was moved to fit around a rock cut next to the track. It was moved too close to the edge. The boat flipped off the rail cars and landed in a canyon. The Libby Press newspaper described it:

She turned over in the fall and lit on her smokestack and is there now, not worth a bad fifty-cent piece, with her bottom up and flat as a pancake.

Later Steamboat Operations on the Upper Columbia

While Armstrong was busy with the Kootenay and Klondike mining booms, a few other boats appeared on the upper Columbia. In 1899, H.E. Forster, a rich politician and occasional steamboat captain, brought the Selkirk by rail from Shuswap Lake to Golden. He launched her there. But he used her as a yacht, not for commercial work at first. Also, Captain Alexander Blakely bought the small sidewheeler Pert and operated her on the river.

In 1899, the Duchess was involved in the Stolen Church Affair. This was a dispute over who owned a church in Donald. One group packed up the entire church and moved it to Golden. The other group removed the church bell while it was on the Duchess on its way to Golden. (The church itself was later moved to Windermere, but without the bell.)

In 1902, the Duchess was taken apart. In 1903, Captain Armstrong built a new steamer, the Ptarmigan. He used the engines from the old Duchess, which were over 60 years old by then! In 1911, the same engines were put into the newly built steamer Nowitka.

With more railways being built and the economic problems from Canada joining the Great War, steamboat activity slowed down around 1915. Many steamboat men from the route went to war. Captain Armstrong oversaw British river transport in the Middle East, on the Nile and Tigris rivers. Captain Blakey's son, John Blakely (1889–1963), had trained under his father and Captain Armstrong. He went to Europe and was one of only six survivors when his ship was torpedoed in the English Channel.

The Last Steamboat Runs

Nowitka made the last steamboat trip on the upper Columbia in May 1920. Under Captain Armstrong, she pushed a pile driver to build a bridge at Brisco, northwest of Invermere. When the bridge was finished, it was too low for a steamboat to pass under it.

Armstrong himself found work with the government after returning from the war. He was badly hurt in an accident in Nelson, BC. He died in a hospital in Vancouver, BC in January 1923. His life covered the entire history of steamboat travel in the Rocky Mountain Trench, from 1886 to 1920. In 1948, Captain John Blakely built his own sternwheeler, the Radium Queen. It had to be small enough to fit under the Brisco bridge.

Finding Old Steamboat Wrecks

In April 2001, members of the Kootenay Chapter of the British Columbia Underwater Archaeological Society ("BCUAS") found two previously unknown shipwrecks. They were near the old Columbia River Lumber Company mill. The two boat bodies were buried deep in mud. The team believed one of the boats was the Nowitka.

The expedition also found and mapped the wreck of the F.P. Armstrong. This was within 2 kilometers of Columbia Lake. Most of the Armstrong wreck is under 50 to 80 centimeters of mud. Some wood paneling, thought to be from the deck or upper part of the boat, was found downstream. The team used a metal detector. Their findings showed that the machinery and boiler had been removed from the boat's body. Downstream, near the Riverside Golf Course, the expedition found a larger wreck. About 8 meters of its hull (boat body) framing was visible. The hull was 7 meters wide. This was wider than any boat ever put on the upper Columbia, except for the North Star. It could not be determined if this was a powered boat or an unpowered barge.

List of Steamboats

| Name | Year Built | Registra- tion # |

Mills # | Gross Tons | Reg. Tons | Length | Beam | Depth | Engines | Disposition |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Duchess (1886) |

1886 | 32 | 60 ft (18 m) | 17 ft (5 m) | 4 ft (1 m) | 8" x 30" | Taken apart 1888, engines moved to Duchess (1888) | |||

| Clive | 1879 | 20 | 31 ft (9 m) | 9.3 ft (3 m) | 4.0 ft (1 m) | single cylinder 5.5" x 8" | Sank near Spillmacheen 1887. | |||

Duchess (1888) |

1888 | 90800 | 014610 | 145.5 | 99.5 | 81.6 ft (25 m) | 17.3 ft (5 m) | 4.6 ft (1 m) | 8" x 30" | Taken apart 1901 or 1902, engines moved to Ptarmigan |

Marion |

1888 | 94801 | 035040 | 14.8 | 9.3 | 61 ft (19 m) | 10.3 ft (3 m) | 3.6 ft (1 m) | 5.5" x 8" | Moved to Arrow Lakes 1890. |

Pert |

1890 | 107826 | 042920 | 6.5 | 4.0 | 49.8 ft (15 m) | 10 ft (3 m) | 2.6 ft (1 m) | 5" x 6" | Abandoned at Windermere Lake 1905 |

Hyak |

1892 | 100637 | 024760 | 39 | 24.6 | 81 ft (25 m) | 11.2 ft (3 m) | 3.9 ft (1 m) | 6" x 24" | Stopped operating 1906 |

Gwendoline |

1893 | 100805 | 022400 | 91 | 57 | 63.5 ft (19 m) | 19 ft (6 m) | 3.2 ft (1 m) | 8" x 36" | Returned to Kootenay River, spring 1894 (see chart below for final disposition). |

Selkirk 1895 |

1899 | 103299 | 050990 | 58.5 | 37.5 | 62 ft (19 m) | 11.2 ft (3 m) | 3.6 ft (1 m) | 5" x 24" | Abandoned 1917 at Golden shipyard, still visible on ways in 1926 |

North Star |

1897 | US 130739 | 380 | 265 | 130 ft (40 m) | 26 ft (8 m) | 4.0 ft (1 m) | 14" x 48" | Moved through Baillie-Grohman Canal in 1902 from Kootenay River to Columbia River. Technically seized by customs at Golden in 1903; stored and gradually taken apart with parts used for other steamers. | |

Ptarmigan |

1903 | 111950 | 044870 | 246.5 | 155 | 110.5 ft (34 m) | 20.5 ft (6 m) | 4 ft (1 m) | 8" x 30" | Taken apart 1909, engines moved to Nowitka. |

Isabella McCormack |

1908 | 122399 | 025730 | 178 | 112 | 94.9 ft (29 m) | 18.8 ft (6 m) | 3.5 ft (1 m) | 7" x 42" | Beached 1910 at Althalmer, BC, and turned into a houseboat. Engines moved to Klahowya. |

Klahowya |

1910 | 126946 | 029880 | 175 | 111 | 92 ft (28 m) | 19 ft (6 m) | 3.5 ft (1 m) | 7" x 42" | Stopped operating 1915 |

| Nowitka | 1913 | 130604 | 040720 | 82 | 62 | 80.5 ft (25 m) | 19 ft (6 m) | 3.5 ft (1 m) | 8" x 30" | Stopped operating May 1920 |

F.P. Armstrong |

1913 | 134032 | 017430 | 126 | 79 | 81 ft (25 m) | 20 ft (6 m) | 4.0 ft (1 m) | 12" x 72" | Abandoned near Fairmont Hot Springs, BC around 1920. |

Invermere |

1912 | 130892 | 025370 | 66 | 75 ft (23 m) | 13 ft (4 m) | 4.0 ft (1 m) | propeller-driven, gasoline or diesel engine | ||

| Muskrat (1892) | 1892 | none | 038440 | 84 ft (26 m) | 20 ft (6 m) | Government snag boat |

| Name | Year Built | Registra- tion # |

Jones # | Gross Tons | Reg. Tons | Length | Beam | Depth | Engines | Disposition |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Annerly |

1892 | US #106963 | 128 | 80 | 92.5 ft (28 m) | 16 ft (5 m) | 4.4 ft (1 m) | Broken up 1896 | ||

| Gwendoline | 1893 | 100805 | 022400 | 91 | 57 | 63.5 ft (19 m) | 19 ft (6 m) | 3.2 ft (1 m) | 8" x 36" | Toppled off flat car during rail transfer to lower Kootenay River, June 1899, fell in canyon and was a total loss |

| Fool Hen | 1894 | Taken apart, engines moved to Libby | ||||||||

| Libby | 1895 | steam engine | ||||||||

| Rustler | 1896 | US 111114 | 258 | 196 | 124 ft (38 m) | 22 ft (7 m) | 4.0 ft (1 m) | 10" x 72" | Wrecked in Jennings Canyon, 1896, after being in service only 6 weeks. | |

| Ruth | 1896 | US 111113 | 315 | 275 | 131 ft (40 m) | 22 ft (7 m) | 4.5 ft (1 m) | 10" x 74" | Lost control at The Elbow in Jennings Canyon and destroyed in collision with Gwendoline, 1897 | |

J.D. Farrell |

1897 | 100687 | 359 | 226 | 130 ft (40 m) | 26 ft (8 m) | 4.5 ft (1 m) | Taken apart 1903, engines, boiler, fittings and major parts of upper structure moved to Lake Pend Oreille sternwheeler Spokane (1903). | ||

North Star |

1897 | 130739 | 380 | 265 | 130 ft (40 m) | 26 ft (8 m) | 4.0 ft (1 m) | 14" x 48" | Moved through Baillie-Grohman Canal in 1902 to Columbia River. See table above for what happened to it later. |