Rocky Mountain Trench facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Rocky Mountain Trench |

|

|---|---|

Kinbasket Lake lies in the Rocky Mountain Trench

|

|

| Floor elevation | 600–900 m (2,000–3,000 ft) |

| Length | 1,600 km (1,000 mi) |

| Width | 3–16 km (2–10 mi) |

| Geography | |

The Rocky Mountain Trench, also called the Valley of a Thousand Peaks, is a huge valley in western North America. It runs along the western side of the northern Rocky Mountains. This valley is a very clear feature on maps and when seen from above. It stretches about 1,600 kilometers (1,000 miles). It goes from Flathead Lake in Montana all the way to the Liard River near the British Columbia–Yukon border.

The bottom of the Trench is usually 3 to 16 kilometers (2 to 10 miles) wide. It sits about 600 to 900 meters (2,000 to 3,000 feet) above sea level. The valley runs almost perfectly straight from southeast to northwest. This makes it a helpful guide for pilots flying north or south.

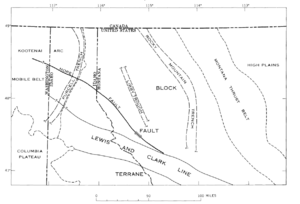

Even though glaciers have carved some parts of it into U-shaped valleys, the Trench was mostly formed by cracks in the Earth's crust called geologic faults. It separates the Rocky Mountains to the east from the Columbia and Cassiar Mountains to the west. It also borders part of the McGregor Plateau in British Columbia. The Trench can be up to 25 kilometers (16 miles) wide if you measure from peak to peak. It is easy to see from airplanes, satellites, or from the top of nearby mountains.

Contents

Rivers and Lakes of the Trench

The Rocky Mountain Trench is home to parts of four major river systems. These are the Columbia River, Fraser River, Peace River, and Liard River. Today, two large reservoirs, Lake Koocanusa and Kinbasket Lake, fill much of the Trench's length. These were created as part of the Columbia River Treaty. Another reservoir, Williston Lake, was also formed by a power project in British Columbia.

Many rivers flow along the Trench, at least for some distance. These include the Kootenay River, Columbia River, Canoe River, Flathead River, Fraser River, Parsnip River, Finlay River, Fox River, and Kechika River. The North Fork of the Flathead River flows into Flathead Lake and is part of the Columbia River system. The Kechika River is part of the Liard River system. The Fox, Parsnip, and Finlay Rivers are part of the Peace River system. The Canoe River is a short river that flows into Kinbasket Lake, which is a reservoir on the Columbia River.

The Kootenay River does not stay entirely within the Trench. It leaves Canada southwest through Lake Koocanusa. It then joins the Columbia River in Castlegar, British Columbia, after flowing through the United States.

Northern and Southern Parts of the Trench

For easier understanding, the Rocky Mountain Trench is often split into two parts: the Northern Rocky Mountain Trench and the Southern Rocky Mountain Trench. The dividing line is around 54°N, near Prince George, British Columbia. This point marks where rivers start flowing north and east towards the Arctic Ocean, instead of south and west towards the Pacific Ocean.

The northern part of the Trench was mainly formed by a type of fault called a strike-slip fault. In contrast, the southern part was created by normal faults. Even though they formed differently and at different times, both parts line up. This is because their formation was guided by an older, deep rock layer that had a large vertical drop.

Northern Rocky Mountain Trench: Geography and History

The Northern Rocky Mountain Trench is very close to the Tintina Trench near the British Columbia-Yukon border. Some people even consider them to be the same or extensions of each other. The Tintina Trench continues further northwest into the Yukon and Alaska. The visible parts of both trenches disappear under the forests of the Liard Plain, near the towns of Watson Lake, Yukon, and Lower Post, BC. The highest point in the northern Trench is Sifton Pass, which is about 1,010 meters (3,314 feet) high.

How the Northern Trench Formed

The movement of the Tintina Fault, which runs along the Tintina-Northern Rocky Mountain Trench, likely started around the middle Jurassic period. The fastest movements probably happened in two bursts: one in the middle Cretaceous period and another in the early Cenozoic period. The later movement likely occurred during the Eocene epoch.

Overall, the land to the west of this fault system has moved about 750 to 900 kilometers (466 to 559 miles) north. About 450 kilometers (280 miles) of this movement has happened since the mid-Cretaceous. This type of movement is related to other major faults in western North America, like the San Andreas Fault.

Travel and Exploration in the Northern Trench

First Nations people have always traveled through the northern Trench. After Europeans arrived, many expeditions also explored this area. Today, much of the northern Trench remains wild. The northern 300 kilometers (186 miles) have almost no roads, only some rough trails used for fire control, hunting, or logging.

It's interesting that this natural travel route in northern British Columbia has stayed wild. This is due to various events and decisions made since 1824. Even though many government maps since 1897 showed a passable trail, it can be hard to find today. This is because of changes in the land from beaver dams or forest fires. Only local Indigenous people and experienced Kaska natives can easily follow it. Today, it is more often used as a route for airplanes.

The northern Trench, from the Highway 97 bridge on the Parsnip River, has routes on both sides of Williston Lake to Fort Ware. The road on the east side cannot be used because of the Peace Reach reservoir. Travelers use a gravel road on the west side of the reservoir to get to Ware. Beyond that, the road becomes a very narrow path, only a few kilometers long.

The Kaska Dena people of Fort Ware and Lower Post call their ancient travel route "The Trail of The Ancient Ones." They also call it the "Davie Trail," named after David Braconnier, who founded the community at Ware.

- 1797: John Finlay explored parts of the Finlay and Parsnip Rivers. The Finlay River was later named after him.

- 1823-1825: Samuel Black of the Hudson's Bay Company traveled north through Finlay Forks to the Fox River. He almost reached the Liard River but decided to explore the Finlay River's source instead.

- 1831: John Macleod of the Hudson's Bay Company recorded the Kechika River flowing into the Liard River from the northern end of the Trench.

- 1872: Captain William F. Butler explored part of the Finlay River and noted the Fox River and Fox Lake.

- 1897-1898: The Canadian government sent Inspector Moodie's police patrol to map a supply route from the Peace River to the Yukon. They proved the route was possible.

- 1898: McGregor's book mentioned that many groups traveled the route from Fox River to Sylvestre's Landing. There were also reports of cattle being driven along this route.

- 1906: A North West Mounted Police patrol began building the Police Trail westward from Hudson Hope and then north up the Trench from Fort Graham.

- 1907: British Columbia Premier R. McBride asked Canada to redirect police efforts to connect with the more western "Telegraph Trail." This trail was later abandoned because it was not practical.

- 1912: Prospector Bower reported that Sifton Pass was the best route for a railway from the Fraser River to the Yukon.

- 1914: Premier McBride supported building a railway along Inspector Moodie's route.

- 1926: Whitewater Post was established by the Hudson's Bay Company.

- 1930-1931: The British Columbia Department of Public Works looked into building a road over Sifton Pass.

- 1934: Charles Bedaux led the Bedaux Expedition. His team had to stop their mission due to tiredness and lack of supplies.

- 1942: A decision was made to build the Alaska Highway (Alcan Highway), which bypassed the Northern Trench.

- 1942: The American government secretly surveyed the Northern Rocky Mountain Trench for a military railway link. The project was later declined.

- 1949: The U.S. Congress approved a survey for a railway from Prince George to Fairbanks.

- 1950: Canadian Transport Minister Lionel Chevrier proposed the 1942 railway route to the Federal Cabinet.

- 1953: Whitewater Post (Kwadacha) of the Hudson's Bay Company closed. Today, Fort Ware remains a full-time settlement.

- 1957: Axel Wenner-Gren proposed large-scale developments for the Peace River area, including a monorail up the Northern Trench.

- 1960-1967: The British Columbia Government chose a western route for their strategic railway instead of the Northern Trench. This was partly because parts of the Finlay and Parsnip Rivers in the Trench would be flooded by the Peace River dam.

- 1964: The U.S. Congress considered the NAWAPA proposal, which would have flooded parts of the Trench as part of a huge water diversion project.

- 1971: Sir Ranulph Fiennes traveled down the Trench as part of his expedition around the world. He was later recognized as the "Greatest Living Explorer."

- 1981: "Skook" Davidson, a long-time outfitter, suggested creating a national park in the Northern Trench.

- 1998: The British Columbia Government began steps to create the Muskwa-Kechika Management Area.

- 1999: Karsten Heuer completed the final part of the Y2Y (Yellowstone to Yukon) hike at Lower Post.

- 2000: The Muskwa-Kechika Management Area was extended into the Northern Trench. Much of the northernmost part of the Trench is now a protected area.

Even in 2009, the Northern Trench was still considered a possible route for the 120-year-old idea of a Canada Alaska Railway. Experts still debate if this route is the best choice, even though it is lower, more direct, has fewer major river crossings, and less snow.

Southern Rocky Mountain Trench: Geography and Economy

The Southern Rocky Mountain Trench makes up about half of the Trench in British Columbia. It includes three areas: the Robson Valley, Columbia Valley, and East Kootenay. Many communities are located here, along with two major reservoirs: Kinbasket Lake and Lake Koocanusa.

How the Southern Trench Formed

The Southern Rocky Mountain Trench was mainly formed by normal faulting during the Cenozoic era. This means the Earth's crust pulled apart, causing blocks of land to drop down. Any side-to-side movement (strike-slip) in the southern Trench is not very important. The pulling apart of the crust was very strong, extending as deep as 13.5 kilometers (8.4 miles).

The southern Trench is also different from the northern Trench because it is more winding and not symmetrical across its width. The western side of the Southern Rocky Mountain Trench is less steep and more uneven than the eastern side.

Regions of the Southern Trench

There are four main geographic parts of the Southern Rocky Mountain Trench:

- The part of the Trench that includes the upper Fraser River, east of Prince George and continuing southeast to Valemount, is called the Robson Valley. It is named after Mount Robson, which stands at its southern end. Valemount is the western entrance to the Yellowhead Pass.

- From Valemount and Canoe southeast to the eastern exit of Rogers Pass at Donald, BC, the Trench holds the waters of Kinbasket Lake. This reservoir was created by the Mica Dam. Before the reservoir, this area was part of the "Big Bend Highway," which was replaced by the Trans-Canada Highway in the 1960s.

- The Trench from Golden extending southeast to the source of the Columbia River at Columbia Lake is known as the Columbia Valley. Golden is the western entrance to the Kicking Horse Pass on Highway #1, which goes east to Alberta.

- The southernmost Canadian part of the Trench is the heart of the East Kootenay region. This area, near Cranbrook, British Columbia, is much wider than the Trench to the northwest. It forms a broad basin rather than the U-shaped valley seen elsewhere. This part splits near Wasa, about 100 kilometers (62 miles) north of the U.S. border. The western fork leads to the cities of Cranbrook and Kimberley. Elko is the western entrance to the Crowsnest Pass on Highway 3, which goes east to Alberta.

The Trench continues south into Montana. There, it holds Lake Koocanusa, a reservoir on the Kootenay River created by the Libby Dam.

Economy and Tourism

The large valley and its smaller valleys have always supported an economy based on ranching and logging. This has been boosted by the discovery of several mines in the side valleys. These mines produce lead, zinc, coal, and gypsum. The Canadian Pacific Railway (CPR) also built a railway line that goes north up the southern Trench between Cranbrook and Golden. This line connects the southern Crowsnest Pass railway route to the CPR mainline through Rogers Pass. Today, it carries coal to Tsawwassen for export. Another railway link through Yahk allows freight to be shipped into Idaho and the western U.S.

Tourism has become a big part of the economy. The Southern Trench is known for its many ski resorts, either in the Trench itself or in nearby valleys. These include Fairmont, Panorama, Kimberley, Purden, Kicking Horse, and the original Bugaboo heli-ski lodge. Many other ski touring and backcountry lodges are also found here. In the summer, people enjoy golf, boating, fishing, and hiking. These activities attract more and more visitors and people who want to live there.

Hunting, fishing, off-roading, and camping are also popular activities. These include guided tours and individual adventures. The combination of low elevation, good weather, beautiful scenery, diverse recreation, and resorts has led to a growing real estate industry. This is especially true for communities and rural areas around Cranbrook, Windermere, Invermere, Radium, and Golden. There are also many smaller communities and post offices in the area.

Communities in the Trench

The Trench is home to several communities, from north to south:

- Lower Post, British Columbia

- Fort Ware (Kwadacha)

- Ingenika Point

- Mesilinka

- Fort Grahame

- Mackenzie, British Columbia

- Holmes River, British Columbia

- McBride, British Columbia

- Tête Jaune Cache, British Columbia

- Valemount, British Columbia

- Boat Encampment

- Golden, British Columbia

- Radium Hot Springs, British Columbia

- Invermere, British Columbia

- Fairmont Hot Springs, British Columbia

- Canal Flats, British Columbia

- Kimberley, British Columbia

- Cranbrook, British Columbia

- Eureka, Montana

- Whitefish, Montana

- Kalispell, Montana

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Trinchera de las Montañas Rocosas para niños

In Spanish: Trinchera de las Montañas Rocosas para niños

| John T. Biggers |

| Thomas Blackshear |

| Mark Bradford |

| Beverly Buchanan |