Stefan Dušan facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Stefan DušanСтефан Душан |

|

|---|---|

| Emperor of the Serbs and Greeks | |

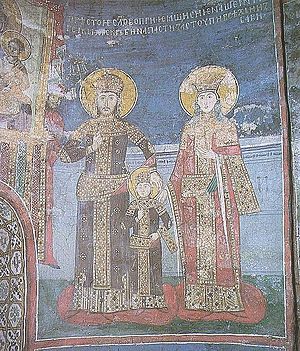

Detail of fresco in the Lesnovo Monastery, 1350.

|

|

| King of all Serbian and Maritime Lands | |

| Reign | 8 September 1331 – 16 April 1346 |

| Predecessor | Stefan Uroš III |

| Successor | Stefan Uroš V |

| Emperor of the Serbs | |

| Reign | 16 April 1346 – 20 December 1355 |

| Coronation | 16 April 1346, Skopje |

| Successor | Stefan Uroš V |

| Born | c. 1308 |

| Died | 20 December 1355 (aged 46–47) Serbian Empire |

| Burial | Monastery of the Holy Archangels; after 1927: St. Mark's Church |

| Spouse | Helena of Bulgaria |

| Issue | Stefan Uroš V |

| Dynasty | Nemanjić |

| Father | Stefan Uroš III |

| Mother | Theodora Smilets of Bulgaria |

| Religion | Serbian Orthodox |

Stefan Uroš IV Dušan (Serbian Cyrillic: Стефан Урош IV Душан), also known as Dušan the Mighty (Serbian: Душан Силни), was a powerful ruler. He was the King of Serbia from 1331. Later, in 1346, he became the Emperor of Serbs and Greeks, Albanians and Bulgarians. He ruled until his death in 1355.

Dušan conquered a huge part of Southeast Europe. This made him one of the most powerful rulers of his time. Under Dušan, Serbia became the strongest country in Southeast Europe. It was a large Eastern Orthodox empire with many different peoples and languages. His empire stretched from the Danube River in the north to the Gulf of Corinth in the south. Its capital city was Skopje.

He created a set of laws for the Serbian Empire, called Dušan's Code. This was a very important document for medieval Serbia. Dušan also helped the Serbian Orthodox Church grow. He changed it from an archbishopric to a patriarchate. He also finished building the Visoki Dečani Monastery, which is now a UNESCO World Heritage site. He also founded the monastery of the Holy Archangels. During his rule, Serbia reached its greatest size, power, wealth, and culture.

After Dušan's sudden death in 1355, his empire started to get weaker. When his son and successor, Emperor Stefan Uroš V, died, the Serbian Empire broke into many smaller, independent Serbian states. Among these, the Serbian Despotate became the most important, ruled by the Lazarević dynasty.

Contents

Early Life and Rise to Power

In 1314, King Stefan Milutin of Serbia had a disagreement with his son, Stefan Uroš III. Milutin sent his son, also known as Dečanski, to Constantinople to be blinded. However, he was not completely blinded. Dečanski later returned to Serbia in 1320. He was given control of the area called 'Budimlje' (modern Berane). His half-brother, Stefan Konstantin, ruled the province of Zeta.

King Milutin died in 1321. Konstantin was crowned king, but a civil war started right away. Dečanski and his cousin, Stefan Vladislav II, both wanted the throne. Dečanski invaded Zeta, defeated, and killed Konstantin. Dečanski was crowned king in 1322. His son, Stefan Dušan, was crowned "young king." Dečanski later gave Zeta to Dušan, showing that Dušan was meant to be the next ruler. By 1326, Dušan was known as the "young king" and ruler of Zeta and Zahumlje. Some historians believe Dušan was born in 1312, not around 1308, based on these records.

Meanwhile, Vladislav II gathered support in Rudnik. He declared himself king and was supported by the Hungarians. In 1323, war broke out between Dečanski and Vladislav. By the end of 1323, Dečanski had taken Rudnik. Vladislav was defeated in 1324 and fled to Hungary. This left Dečanski as the undisputed "King of All Serbian and Maritime lands."

Dušan's Youth and Taking the Throne

Dušan was the oldest son of King Stefan Dečanski and Theodora Smilets. His mother was the daughter of Emperor Smilets of Bulgaria. Dušan was born around 1308 or in 1312 in Serbia. From 1314 to 1320, his family lived in Constantinople while his father was in exile. In Constantinople, Dušan learned Greek and understood Byzantine life and culture. He was very interested in war. As a young man, he fought well in two important battles. In 1329, he defeated Stephen II Kotromanić in the War of Hum. In 1330, he defeated the Bulgarian emperor Michael III Shishman in the Battle of Velbužd.

After the victory at Velbazhd, King Dečanski chose not to attack the Byzantines. This upset many nobles who wanted to expand south. By early 1331, Dušan was arguing with his father. Some sources say that advisors turned Dečanski against his son. Dečanski sent an army against Dušan, but Dušan managed to escape. After a short period of trouble, father and son made peace in April 1331.

However, three months later, Dečanski ordered Dušan to meet him. Dušan feared for his life. His advisors told him to resist. So, Dušan marched from Skadar to Nerodimlje and surrounded his father. Dečanski fled, but Dušan captured the royal treasury and family. Dušan then caught up with his father at Petrich. On August 21, 1331, Dečanski surrendered. On the advice of Dušan's advisors, he was imprisoned. Dušan was crowned King of All Serbian and Maritime lands in early September.

The civil war in Serbia had stopped Serbia from helping Ivan Stephen and Anna Neda in Bulgaria. They were removed from power in March 1331. The new Bulgarian Emperor, Ivan Alexander of Bulgaria, feared Serbia. So, he quickly sought peace with Dušan. Dušan wanted to move against the richer Byzantine Empire. So, the two rulers made peace and an alliance in December 1331. This alliance was sealed when Dušan married Ivan Alexander's sister, Helena.

Dušan's Character

Writers from Dušan's time said he was very tall and strong. They described him as "the tallest man of his time." He was also very handsome and a dynamic leader. He had quick intelligence and strength, showing a "kingly presence." According to pictures from that time, he had dark hair and brown eyes. As an adult, he grew a beard and longer hair.

Dušan's Reign

Serbia made some attacks into the Macedonia region in late 1331. However, a big attack on Byzantium was delayed. Dušan had to stop rebellions in Zeta in 1332. The Zetan nobles might have been upset because they didn't get the rewards they were promised. Dušan put down this rebellion in the same year.

Dušan started fighting the Byzantine Empire in 1334. These wars continued off and on until he died in 1355. He also fought with the Hungarians twice, but these were mostly defensive battles. Dušan's armies were first defeated by Charles I of Hungary's large army in Šumadija in 1336. But as the Hungarians moved south, Dušan's cavalry attacked them in open fields. This caused the Hungarian troops to retreat north of the Danube River. Charles I was wounded but survived. As a result, the Hungarians lost Mačva and Belgrade. Dušan then focused on his country's internal matters. In 1349, he wrote the first law book for the Serbs.

To the west, Dušan won battles against Hungarian leader Louis the Great. This gave him the eastern part of modern Bosnia. Dušan also defeated Louis's vassals, like the Croatian ban and Hungarian commanders. He was at peace with Tsar Ivan Alexander of Bulgaria. Ivan Alexander even helped him sometimes. Serbia became the most powerful state between 1331 and 1365.

Dušan took advantage of the civil war in the Byzantine Empire. This war was between the regent Anna of Savoy and general John VI Kantakouzenos. Dušan and Ivan Alexander supported different sides. But they remained at peace with each other. They both used the Byzantine civil war to gain more land for themselves.

Dušan's main attacks began in 1342. He eventually conquered all Byzantine lands in the western Balkans up to Kavala. He did not take the Peloponnesus or Thessaloniki because he didn't have a strong navy. Some people think Dušan wanted to conquer Constantinople. His goal might have been to replace the weakening Byzantine Empire with a united Orthodox Greco-Serbian Empire under his rule. In 1344, his commander Preljub was stopped by a Turkic force at Stephaniana. The Turks won, but it wasn't enough to stop Serbia from conquering Macedonia. Because of Dušan's attacks, the Byzantines sought help from the Ottoman Turks. This was the first time the Turks were brought into Europe.

In 1343, Dušan added "of Romans (Greeks)" to his title. He called himself "King of Serbia, Albania and the coast." In another document, he called himself "King of the Bulgarians." In 1345, he started calling himself tsar, which means Emperor. This was written in documents from November 1345 and January 1346. Around Christmas 1345, at a meeting in Serres, he declared himself "Tsar of the Serbs and Romans."

Becoming Emperor and Church Independence

On April 16, 1346 (Easter), Dušan held a huge meeting in Skopje. Important church leaders were there, including the Serbian Archbishop Joanikije II and the Bulgarian Patriarch Simeon. They all agreed to raise the independent Serbian Archbishopric to the status of a Serbian Patriarchate. From then on, the Archbishop was called the Serbian Patriarch. The first Serbian Patriarch, Joanikije II, then crowned Dušan as "Emperor and autocrat of Serbs and Romans." Dušan also had his son Uroš crowned King of Serbs and Greeks. This gave Uroš nominal rule over the Serbian lands. Dušan, however, still governed the whole state. He had a special responsibility for the Eastern Roman lands.

After this, the Serbian court became more like the Byzantine court. This was seen in court ceremonies and titles. As Emperor, Dušan could grant titles that only an Emperor could give. His half-brother Symeon Uroš and brother-in-law Jovan Asen became despotes. His other brother-in-law Dejan Dragaš and Branko Mladenović received the title of sebastocrator. Military commanders like Preljub and Vojihna were given the title of caesar. With the Serbian Patriarchate, bishoprics became metropolitans, like the Metropolitanate of Skopje.

The Serbian Patriarchate took control over Mount Athos and the Greek church areas. These had been under the Ecumenical Patriarchate of Constantinople. The Archbishopric of Ohrid remained independent. Because of these actions, Dušan was excommunicated by the Ecumenical Patriarch of Constantinople in 1350. However, this did not stop Dušan's good relations with Mount Athos. The monks there still called him Emperor.

Expanding the Empire

In 1347, Dušan conquered Epirus, Aetolia, and Acarnania. He made his half-brother, Simeon Uroš, the governor of these areas. In 1348, Dušan also conquered Thessaly, appointing Preljub as its governor. In eastern Macedonia, he made Vojihna the governor of Drama.

Once Dušan had conquered Byzantine lands in the west, he wanted to take Constantinople. To do this, he needed a strong navy. He knew that the navies of the southern Serbian Dalmatian towns were not strong enough. So, he started talking with Venice, with whom he had good relations. Venice was worried that if Serbs controlled Constantinople, their trading privileges in the Empire would be reduced. Venice chose not to form a military alliance with Serbia. While Dušan wanted Venice's help against Byzantium, Venice wanted Serbia's help against the Hungarians over Dalmatia. Venice politely refused Dušan's offers of help.

While Dušan was fighting in Bosnia, Kantakouzenos tried to get back lands Byzantium had lost. The patriarch of Constantinople, Kallistos, excommunicated Dušan. This was to discourage the Greek people in Dušan's provinces from supporting the Serbian government. However, the excommunication did not stop Dušan's relations with Mount Athos.

Kantakouzenos gathered a small army and took the Chalcidic peninsula, then Veria and Voden. Veria was a very rich town. Dušan had replaced many Greeks with Serbs there, including a Serb army. But the local people opened the gates for Kantakouzenos in 1350. Voden resisted but was taken by force. Kantakouzenos then marched toward Thessaly. He was stopped at Servia by Caesar Preljub and his army. The Byzantine forces went back to Veria. When Dušan heard about the Byzantine campaign, he quickly gathered his forces from Bosnia and marched to Thessaly.

War with Bosnia

Dušan wanted to take back areas that Serbia had controlled before. One of these was Hum, which the Bosnian Ban Stephen II Kotromanić had taken in 1326. In 1329, Ban Stephen II attacked Lord Vitomir. Dušan defeated the Bosnian army at Pribojska Banja. The Ban soon took over Nevesinje and the rest of Bosnia. Petar Toljenović, a relative of Dušan, started a rebellion against the new ruler. But he was captured and died in prison.

In 1350, Dušan attacked Bosnia. He wanted to get back Hum and stop raids on his lands in Konavle. Venice tried to make peace but failed. In October, Dušan invaded Hum with a large army. He successfully took part of the disputed area. Many nobles in Hum were ready to betray the Ban and support Dušan. The Bosnian Ban avoided a big battle. He retreated to the mountains and made small, quick attacks. Most of Bosnia's fortresses held out, but some nobles surrendered to Dušan. The Serbs damaged much of the countryside. Dušan tried to negotiate peace with the Ban. He offered to marry his son Uroš to Stephen's daughter Elizabeth. She would receive Hum as her dowry, returning it to Serbia. But the Ban did not accept this offer.

Dušan might have also started the campaign to help his sister, Jelena. She had married Mladen III Šubić in 1347. Mladen died from the Black Death in 1348. Jelena wanted to keep control of the cities for herself and her son. But Hungary and Venice challenged her. So, Dušan's troops in western Hum and Croatia might have been there to help her.

Death of Dušan

Dušan had big plans. He wanted to control Belgrade, Mačva, and Hum. He also wanted to conquer Durrës, Phillipopolis, Adrianople, Thessalonica, and Constantinople. His ultimate goal was to lead a large army to drive the Muslim Turks out of Europe. However, he fell ill and died on December 20, 1355. His early death created a big power gap in the Balkans. This eventually allowed the Turkish invasion and their rule until the early 20th century. He was buried in his monastery, the Saint Archangels Monastery near Prizren.

His empire slowly fell apart. His son and successor, Stefan Uroš V, could not keep the empire together. Many powerful families gained more power, even though they still called Uroš V Emperor. Simeon Uroš, Dušan's half-brother, declared himself Emperor after Dušan's death. He ruled a large area of Thessaly and Epirus, which Dušan had given him earlier.

Today, Dušan's remains are in the Church of Saint Mark in Belgrade. Dušan is the only ruler of the Nemanjić dynasty who has not been made a saint.

Religious Activities

Like his ancestors, Emperor Dušan was very active in fixing up old churches and monasteries. He also founded new ones. First, he took care of the monasteries where his parents were buried. He generously supported the Banjska monastery, built by King Milutin, where his mother was buried. He also supported the Visoki Dečani monastery, built by his father. The Dečani monastery took eight years to build, and Dušan played a huge role in its construction. Between 1337 and 1339, the emperor became ill. He promised that if he survived, he would build a church and monastery in Jerusalem. At that time, there was one Serbian monastery in Jerusalem and many Serbian monks at the Sinai Peninsula.

His greatest building project was the Saint Archangels Monastery. It is located near the town of Prizren. He was originally buried there. Dušan gave many properties to this monastery. This included the forest of Prizren, which was meant to be a special property for storing precious goods and relics.

His son, Stefan Uroš V, did not make peace with the Patriarch of Constantinople. The first attempt was made by despot Uglješa in 1368. This led to the areas under his rule being returned to Constantinople. The final effort for peace between the churches came from Prince Lazar in 1375. There is no evidence that people worshipped Emperor Dušan as a saint in the decades after his death. Dušan's charter to Ragusa (Dubrovnik) was used as a law for trade between Serbia and Ragusa. Its rules were considered unbreakable. Emperor Dušan's legacy was highly respected in Ragusa. Later folk stories in Serbia had different views of Dušan, mostly negative, influenced by the church.

Church Policy

Dušan did not accept Constantinople's claims of authority over the Serbian Orthodox Church. He thought about joining with the Latin Church (Catholic Church). In 1354, Dušan contacted the Papal States. He offered to recognize Pope Innocent VI as the "father of all Christians." He also offered to unite the Catholic and Serbian Orthodox Churches. In return, he wanted the Pope's support for a military campaign against the Turks. Dušan's plans were welcomed, but they never happened because he died in 1355.

When the Serbian Archbishopric became a Patriarchate, big changes happened in the church. Joanikije II became Patriarch. Bishoprics (Eparchies) became Metropolitanates. New territories from the Ochrid Archbishopric and Ecumenical Constantinople were added to the Serbian church's control. The Ecumenical Patriarchate of Constantinople excommunicated Dušan in 1350. However, this did not affect the church's organization in Serbia.

One of the most important spiritual centers, Mount Athos, came under Serbian control. By November 1345, the monks of Athos accepted Dušan's rule. Dušan guaranteed their independence. He also gave them many economic benefits, with huge gifts and donations. The monks of Chilandar (the birthplace of the Serbian church, founded by Saint Sava) were leaders in the church community.

In his law code, Dušan emphasized his role as a protector of Christianity. He also pointed out the church's independence. The code shows that he cared about parishes being well-organized in both cities and villages. He also looked after some churches and monasteries from Bari in the west to Jerusalem in the east.

Besides Orthodox Christians, there were many Catholics in the Empire. Most lived in coastal cities like Cattaro and Alessio. There were also Catholics at Dušan's court, such as servants from Cattaro and Ragusa, mercenaries, and guests. In the central areas, Saxons were active in mining and trading. Serbia under Dušan defined itself through Orthodoxy and opposition to Catholicism. Catholics were sometimes treated harshly, especially Catholic Albanians.

Royal Ideas and Laws

Some historians believe that Emperor Dušan wanted to create a new Serbian-Greek Empire. This empire would replace the Byzantine Empire. Historian Ćirković thought Dušan's first idea was like that of earlier Bulgarian emperors, who planned to rule together. However, after 1347, relations with John VI Kantakouzenos got worse. Dušan then allied himself with his rival, John V Palaiologos.

Dušan was the first Serbian ruler who wrote most of his letters in Greek. He also signed them with the Imperial red ink. He was the first to publish prostagma, a type of Byzantine document used by Byzantine rulers. In his royal title, Emperor of the Serbs and Greeks, his claim to be the successor of the Eastern Roman (Byzantine) Empire is clear. He also gave Byzantine court titles to his nobles. This practice continued into the 16th century.

Dušan as a Lawmaker

The most lasting thing Dušan did was create a law code. For Dušan's Code, many documents were written. Some important foreign law books were translated into Serbian. However, the third part of the Code was new and uniquely Serbian. It still had Byzantine influences and followed a long legal tradition in Serbia. Dušan explained that his Code's purpose was spiritual. He said it would help his people prepare for the afterlife. The Code was announced on May 21, 1349, in Skopje. It had 155 rules. Another 66 rules were added at Serres in 1353 or 1354. We don't know who wrote the code. But they were probably court members who knew a lot about law.

Dušan's Code covered both religious and everyday matters. This was especially true because Serbia had recently gained full independence for its Orthodox Church under a Patriarchate. The first 38 rules were about the church. They dealt with problems the Medieval Serbian Church faced. The next 25 rules were about the nobility. Civil law was mostly left out. This was because it was covered in older documents, like Saint Sava's Nomokamon and Corpus Juris Civilis. Dušan's Code mainly dealt with criminal law. It strongly focused on the idea of lawfulness, which came directly from Byzantine law.

The original copy of Dušan's Code does not exist anymore. The Code continued to be used as a constitution under Dušan's son, Stefan Uroš V. After the fall of the Serbian Empire in 1371, it was used in all the areas that followed. It was officially used in the next state, the Serbian Despotate, until the Ottoman Empire took it over in 1459. The Code was also used as a guide for Serbian communities under Turkish rule. These communities had a lot of legal freedom in civil cases. The Code was also used in Serbian areas under the Republic of Venice, like Grbalj and Paštrovići.

Military Strength

Serbian military tactics often involved strong cavalry attacks in a wedge shape. Horse archers were on the sides. Many foreign soldiers worked for the Serbian army in the 14th century. These were mostly German knights and Catalan soldiers with halberds. Dušan had his own personal guard of mercenaries. These were German knights led by Palman. Palman became the leader of all mercenaries in the Serbian army in 1331. The main strength of the Serbian army was its heavy cavalry. They were feared for their fierce charges and endurance. Dušan's imperial army was based on the existing military system of Byzantium. His army included Serbian feudal forces, Albanians, and Greeks. Dušan also hired light cavalry made up of 15,000 Albanians. They were armed with spears and swords.

The Serbian expansion into the former Byzantine Empire happened without a single major battle. It was based on surrounding and taking Greek forts.

Titles and Names

He was crowned Young King on January 6, 1322, as the heir apparent. But he was too young to truly rule with his father. Later, in April 1326, Dušan appeared as a co-ruler in Zeta and Zahumlje. He was given the rule of Zeta. So, he ruled as "King of Zeta." In 1331, he took over from his father as "King of all Serbian and Maritime Lands." In 1343, his title was "King of Serbia, Greeks, Albania and the coast." In 1345, he started calling himself tsar, or Emperor. In 1345, he declared himself "Emperor of Serbs and Eastern Romans." On April 16, 1346, he was crowned Emperor of Serbs and Greeks. This title was soon made even bigger to "Emperor and Autocrat of the Serbs and Greeks, the Bulgarians and Albanians."

His nickname Silni (Силни) means the Mighty. It can also mean the Great, the Powerful, or the Strong.

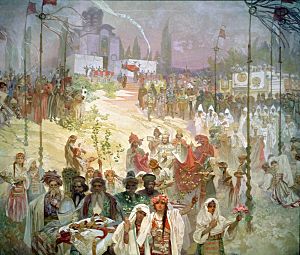

Legacy

Stefan Dušan was the most powerful Serbian ruler in the Middle Ages. He is still seen as a folk hero by Serbs. Dušan lived at the same time as England's Edward III. He is respected in the same way that Bulgarians respect Tsar Simeon I, Poles respect Sigismund I the Old, and Czechs respect Charles IV. According to Steven Runciman, Dušan was "perhaps the most powerful ruler in Europe" during the 14th century. His state was a rival to the strong powers of Byzantium and Hungary. It covered a huge area, which also became its biggest weakness. Dušan was a soldier and a conqueror by nature. He also proved to be a very capable, but feared, ruler. However, his empire slowly fell apart under his son's rule. Local nobles gained more power and moved away from the central government.

The idea of bringing back Serbia as an Empire was a great dream for Serbs. This was true for those living in Ottoman and Austro-Hungarian lands. In 1526, Jovan Nenad called himself Emperor, like Dušan. This was when he ruled a short-lived state of Serbian areas under the Hungarian crown.

The Realm of the Slavs, written by historian Mavro Orbin (around 1550–1614), viewed Emperor Dušan's actions positively. This book was the main source about the early history of South Slavs at the time. Most Western historians got their information about the Slavs from it. Early Serbian historians were influenced by the ideas of their time. They tried to combine information from official documents with stories and family histories. Of the early historians, Jovan Rajić (1726–1801) wrote the most about Dušan's life. Rajić's work greatly influenced Serbian culture then. For decades, it was the main source of information about Serbian history.

After Serbia was restored in the 19th century, people emphasized its connection to the Serbian Middle Ages. They especially focused on its greatest time, during Emperor Dušan's rule. The political goal of restoring his Empire became part of the plans of the Principality of Serbia. This was notably seen in the Načertanije by Ilija Garašanin.

Family Life

With his wife, Helena of Bulgaria, Emperor Dušan had at least one child. This was Stefan Uroš V, who became Emperor after his father. He ruled from 1355 to 1371. According to a Byzantine historian, Dušan also had a daughter named Theodora.

The historian Nicephorus Gregoras said that Dušan was talking about a possible alliance with Orhan in 1351. This would have involved marrying his daughter to Orhan or one of Orhan's sons. However, these talks broke down after Serbian messengers were attacked by Nikephoros II Orsini. The marriage offer was taken back, and Serbia and the Ottoman Empire started fighting again. Theodora likely died between 1352 and 1354.

Some historians think the couple had another child, a daughter. J. Fine suggested it might be "Irene." She was the wife of caesar Preljub (governor of Thessaly, died 1355–1356). She was also the mother of Thomas Preljubović (ruler of Epirus, 1367–1384). In one theory, she married Radoslav Hlapen after her first husband's death in 1360. This idea is not widely accepted.

Foundations

- Saint Archangels Monastery

- Podlastva monastery

- Duljevo monastery

- A large church (27x14m) found near Aranđelovac in 2020

Reconstructions:

- Visoki Dečani

In Fiction

- Epic folk song "Ženidba Cara Dušana" ("Emperor Dušan's wedding").

- 1875 historical three-volume novel "Car Dušan" ("Emperor Dušan") by Dr Vladan Đorđević.

- 1987 historical novel "Stefan Dušan" by Slavomir Nastasijević.

- 2002 historical novel "Dušan Silni" ("Dušan the Great") by Mile Kordić.

See Also

In Spanish: Esteban Dušan para niños

In Spanish: Esteban Dušan para niños

- Serbian Empire

- Serbian Patriarchate of Peć

- Serbian Despotate

- Serbia in the Middle Ages

- Byzantine civil war of 1341–47

- Lesnovo monastery

- Danilo's anonymous pupil