Stone Bridge and the Oregon Central Military Wagon Road facts for kids

Quick facts for kids |

|

|

Stone Bridge and Oregon Central Military Wagon Road

|

|

Stone Bridge during low water period, 1967

|

|

| Location | Rural Lake County, Oregon |

|---|---|

| Nearest city | Lakeview, Oregon |

| Built | 1867-1872 |

| Architectural style | Primitive causeway and wagon trace |

| NRHP reference No. | 74001689 |

| Added to NRHP | 1974 |

The Stone Bridge is a special kind of bridge, called a causeway, built by the United States Army way back in 1867. It crosses a marshy area that connects two lakes, Hart Lake and Crump Lake, in a quiet part of Lake County, Oregon.

This bridge was later used as part of the Oregon Central Military Wagon Road, which was finished in 1872. This wagon road later had some legal problems, which were finally decided by the U.S. Supreme Court in 1893. Both the Stone Bridge and the Oregon Central Military Wagon Road were added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1974 because of their important history.

Today, the Stone Bridge is on land claimed by the State of Oregon. The part of the wagon road next to the bridge is owned by the U.S. Government and is managed by the Bureau of Land Management.

Contents

Building Camp Warner

In 1865, the U.S. Army decided it needed a fort near the Warner Lakes. This fort would help stop Native American groups from raiding in the area. Army scouts from Fort Vancouver chose a spot along Honey Creek, west of the Warner Lakes, in what is now Lake County, Oregon.

In 1866, soldiers from the 14th Infantry Regiment were sent from Fort Boise to build the fort. They traveled through Fort Harney and arrived on the east side of the Warner Lakes in late summer. However, the Army couldn't cross the long chain of lakes, which stretched over seventy miles. After some fights with Native Americans, the soldiers decided to build a temporary camp, called Camp Warner, on the east side of the lakes. The camp was not built very well, and the soldiers had a very hard winter. One sergeant even froze to death during a snowstorm.

In the spring of 1867, a different group of soldiers, from the 23rd Infantry Regiment, took over. In February, General George Crook visited Camp Warner. He ordered that the camp be moved to the Honey Creek spot, west of the lakes. To get the Army's wagons and gear across the wet Warner Lakes area, forty men, led by Captain James Henton, were told to build a bridge. This bridge would cross a narrow, marshy channel between Hart Lake and Crump Lake. Soon after they started the bridge, another group of soldiers went ahead to build the new fort. The bridge was finished that summer, and the soldiers moved into the new camp, which was named Fort Warner.

By 1869, the Native American raids in south-central Oregon had stopped, and a peace treaty was signed. Since there were no more raiders, Fort Warner was closed in 1874. Even though the fort is gone, the Stone Bridge that the Army built to cross the Warner wetlands is still there today.

How the Stone Bridge Was Built

The Stone Bridge was the first big structure built in the south-central part of Oregon. It was constructed between May 16 and July 24, 1867. Forty men from the 23rd Infantry Regiment, supervised by Captain James Henton, built it. They chose a narrow, marshy spot that connects Hart Lake and Crump Lake. These are two large lakes at the southern end of the seventy-mile long chain of lakes and wetlands known as the Warner Lakes.

The Stone Bridge is actually a quarter-mile long causeway, not a typical bridge with arches. A causeway is like a raised road built across wet ground or water. The soldiers built it by bringing large basalt rocks and smaller stones from nearby Hart Mountain. They dumped these rocks into the marsh until they formed a solid path. When it was finished, the causeway was probably several feet above the water. It was also wide enough for wagons to drive over it.

The Army stopped using the crossing in 1874 when Fort Warner closed. However, the Oregon Central Military Wagon Road company started using the Stone Bridge to cross the Warner Lakes. But the road company never took care of it. After the military road was no longer used, local ranchers used the causeway to move their cattle for many years. Over time, the causeway slowly sank into the soft, marshy ground. Today, the Stone Bridge is completely underwater, except during very dry periods. Because of this, it is very hard to find.

Building the Wagon Road

Between 1865 and 1869, the United States Congress gave land to the State of Oregon. This land was then given to companies that built military wagon roads. These roads were meant to help the Army move around the state and encourage people to settle along the routes. Congress eventually approved five military wagon roads in Oregon. The first one was approved on July 2, 1865. It was called the Oregon Central Military Wagon Road, and it was planned to run from Eugene, Oregon to Fort Boise in Idaho.

The American Civil War had used up a lot of money from the U.S. government. Also, the State of Oregon didn't have enough money from taxes to build these roads. So, the government paid for the military road projects with land. Private companies were created specifically to build these roads. Congress allowed these companies to claim three sections of land for every mile of road they built. This land was in odd-numbered sections, in a strip about three miles (5 km) wide on either side of the road. As they finished ten-mile (16 km) sections of road, the companies could claim up to thirty sections of land along the route as payment. Once they officially owned the land, the company could sell or rent it out. This helped them get back the money they spent building the road and make a profit for their investors.

Because of this, the road surveyors planned routes that would go through as much good, well-watered land as possible. For example, when the Oregon Central military road reached the top of the Cascade Mountains, it turned south. It went through the upper Deschutes River area into the Klamath Basin to Fort Klamath. It then followed the Williamson and Sprague Rivers, claiming large parts of the Klamath Indian Reservation. The Oregon Central road then wound through the Goose Lake Valley, over the Warner Mountains to Camp Warner. From Camp Warner, it went across Warner Valley, east of Beaty's Butte, and across the south end of Catlow Valley. The road crossed Steens Mountain through Long Hollow, going on to Camp C. F. Smith on Whitehorse Creek. From Camp C. F. Smith, the road continued northeast to the Owyhee River crossing (near present-day Rome), where it connected to an existing wagon road from Winnemucca, Nevada.

The Road's Path

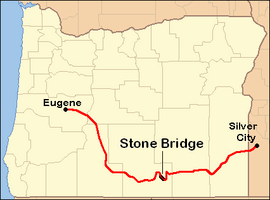

The Oregon Central Military Wagon Road was a winding 420-mile (676 km) path for wagons. It was designed more to claim government land than to connect specific places in the shortest way. Today, Oregon Route 58 (also called the Willamette Pass Highway) follows the first part of the Oregon Central military road. This goes from Eugene over the Cascades to Central Oregon.

From that point, the original road went south through northern Klamath County, past what is now the community of Chemult. It followed the Williamson and Sprague Rivers before turning east into Lake County. The road went over Drews Gap and followed Drews Creek through the north end of the Goose Lake Valley. This part is now mostly followed by Oregon Route 140.

Then, it crossed the Warner Mountains and entered the Warner Valley. It crossed the Warner Lakes at the Stone Bridge, between Crump Lake and Hart Lake. The road continued south of Hart Mountain, through what is now the Hart Mountain National Antelope Refuge. The road crossed the Catlow Valley and then Steens Mountain. It continued through Harney County, entering Malheur County near the Whitehorse Ranch on the east side of the Pueblo Valley. From there, the road followed Crooked Creek northeast, passing near what is now Rome, Oregon. From Rome, it ran along Jordan Creek to Silver City, Idaho.

A Historic Site

The Stone Bridge and the Oregon Central Military Wagon Road were very important projects. They were built by the United States Government and the State of Oregon. Because it is a unique site for military and transportation history, the Stone Bridge and a nearby part of the Oregon Central Military Wagon Road were added to the National Register of Historic Places on November 8, 1974.

Even with this special recognition, both are very hard to find today. A marker was placed at the east end of the Stone Bridge in 1975. However, the causeway itself can only be seen when the water level in the nearby lakes is very low. Some parts of the military road are now part of Oregon's modern road system. In other places, rough dirt roads follow the old route. But most of the original road has completely disappeared.

| Jewel Prestage |

| Ella Baker |

| Fannie Lou Hamer |