Sulphur Bank Mine facts for kids

|

|

| Location | |

|---|---|

| Location | Clearlake Oaks, Lake County |

| California | |

| Country | United States |

| Coordinates | 39°00′14″N 122°39′59″W / 39.00389°N 122.66639°W |

| Production | |

| Products | Borax, Sulfur, Mercury, Gold |

| History | |

| Opened | 1856 (California Borax Co) 1875 (Sulphur Bank Quicksilver Mining Co) 1927 (Bradley Mining Co) |

| Closed | 1957 |

| Reference #: | 428 |

| Owner | |

| Company | Bradley Mining Company |

| Year of acquisition | 1927 |

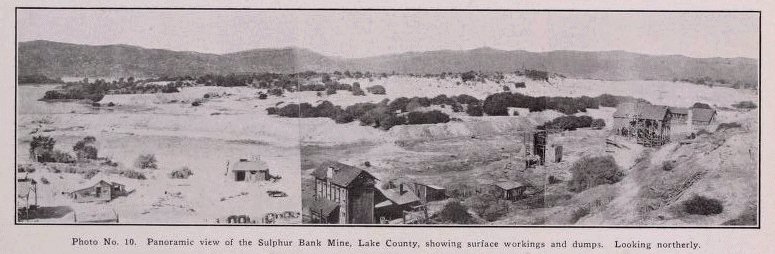

The Sulphur Bank Mine is located near Clearlake Oaks and Clear Lake in Lake County, California. This mine, covering about 150 acres, became one of the most famous places in the world for producing mercury.

For over 150 years, the Sulphur Bank area has attracted many scientists. They have studied its unique geology and, more recently, the effects of mercury pollution. This pollution affects the Cache Creek watershed and the larger Sacramento River-Delta Region and San Francisco Bay.

Contents

History of the Mine

Mining at Sulphur Bank began in 1856, first for borax. Then, in 1865, people started mining for sulfur, producing a lot in just four years. From 1873 to 1957, mercury ore was mined using both underground tunnels and open-pit methods. By 1918, the Sulphur Bank Mine had produced a huge amount of mercury. It was especially important during both World War I and World War II.

The mine closed in 1957 and is now a California Historical Landmark (number 428). In 1990, the Sulphur Bank Mine was added to the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) superfund site list. This means it's a place with serious pollution that needs a big cleanup.

Early Mining Companies

Even though the Sulphur Bank had hot springs with borax, the first big borax mining started nearby at Borax Lake. The California Borax Company began operating there in 1860. This was the first commercial borax mine in the United States. The company also claimed land at Sulphur Bank.

The California Borax Company mined sulfur at Sulphur Bank for a while. However, they found that the sulfur was mixed with cinnabar, which is mercury ore.

Discovering Mercury Ore

Around 1858, people started looking for minerals in the area. This led to the discovery of cinnabar (mercury ore) in 1860. One story says Seth Dunham and L.D. Jones found it while cutting a road. Another account in Scientific American magazine in 1861 said John Newman found it after fires burned off the brush.

These early discoveries didn't lead to much mercury mining until 1872. At that time, the price of mercury went up, and new ways to process the ore were developed. This led to many mercury mines opening in Lake and Napa counties.

The Parrott Family Takes Over

In 1873, a group including Tiburcio and John Parrott, William F. Babcock, and Darius Ogden Mills bought the old California Borax Company. Their goal was to mine mercury at Sulphur Bank.

In 1875, the mine changed its name to the Sulphur Bank Quicksilver Mining Company. Tiburcio Parrott was in charge. He even faced legal trouble for not following a state law about who could work at the mine.

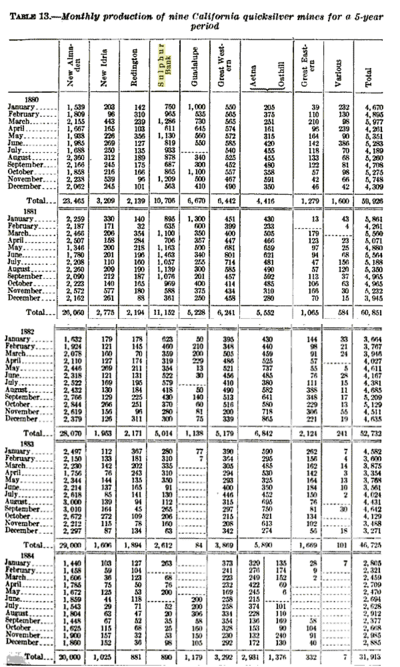

The years from 1875 to 1883 were the busiest for the mine. The Sulphur Bank Quicksilver Mine often produced the most mercury after the New Almaden mine. However, working conditions were very hot underground, sometimes reaching 176°F (80°C). This was because the ore was near hot springs.

Mercury was shipped in iron flasks, each weighing about 90 pounds. The closest train station was 45 miles away in Calistoga. The wagon trip over Mt Saint Helena could take a week or more.

Historians estimate that the mine produced a total of 92,400 flasks of mercury by 1918. Most of this was during the Parrott family's time.

Eastlake Town

The town of Eastlake grew up right next to the mine. The mine's managers lived there. In 1880, many different people worked at the mine. The census showed 218 men from China and 40 men from other countries. Most of the European miners were from Sweden and Norway. Only a few white miners were born in the United States.

How the Mine Worked

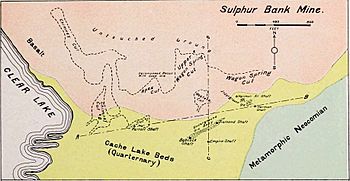

The mercury mine was both an open pit and an underground operation with tunnels. There were three main shafts: the Hermann, the Fiedler, and the Parrott. Miners used these shafts and tunnels to reach the ore.

Mining stopped in certain areas when the hot water and gas made it too difficult to work. Then, a new shaft would be dug nearby.

The cinnabar ore was heated in furnaces to turn the mercury into a gas. This gas was then cooled to become liquid mercury. The waste rock, called calcine, was dumped near the lake shore. All the furnaces used wood for fuel.

End of the Parrott Era

The busy time for mercury mining ended when the price of mercury dropped a lot. The Sulphur Bank Quicksilver Mining Company went bankrupt by 1883. The town of Eastlake was abandoned after the mine closed.

The mine was mostly quiet through the late 1880s and 1890s. In 1901, the Sulphur Bank mine was sold to a group of bankers from New York.

Empire Consolidated Company

By 1902, the Sulphur Bank mine was run by the Empire Consolidated Quicksilver Company. They dug a new shaft called the Empire. However, this company faced many problems and lawsuits.

A newspaper reported in 1901 that New York investors bought the Sulphur Bank and other mines for $1 million. But the deal quickly fell apart. Lawsuits followed, and the company's stock was eventually sold for a very small amount of money. The mines were never fully reopened by this company.

George Ruddock and Bradley Mining Company

Later, George T. Ruddock, a mining engineer, owned the Sulphur Bank mercury mine. He leased it to H.W. Gould. The mine had not been actively worked since 1906.

Ruddock believed there were still hundreds of thousands of tons of valuable ore on the surface. He thought it could be dug up cheaply with a steam shovel. This open-pit mining method was used later when the Bradley Mining Company bought the mine.

The Bradley Mining Company, founded by Frederick Worthen Bradley, bought the Sulphur Bank mercury mine and 700 acres around it in 1927. Frederick's son, Worthen Bradley, became the assistant superintendent.

The Bradley family was interested in the mine because the price of mercury was rising. During the 1930s Depression, the mine opened and closed depending on mercury prices. The Sulphur Bank mercury mine finally closed for good in 1957.

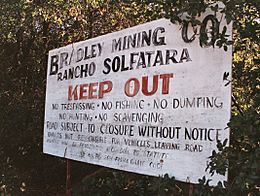

Rancho Solfatara

Frederick Worthen Bradley passed away in 1933. His son, Worthen, then took over the mine. He also developed a summer home called Rancho Solfatara on 800 acres next to the mine. This land was first used to raise cattle to feed the 100 miners who lived there during World War II. During the war, there was a huge demand for mercury because it was used in detonators for munitions.

The Sulphur Bank Mine and Rancho Solfatara are still owned by the Bradley Mining Company and the Worthen Bradley Trust today.

The Mine Today

Today, the mine site has mine tailings (waste rock) and a flooded open pit mine called the Herman Impoundment or Herman Pit. About two million cubic yards of mine waste are still on the site.

The Herman pit is filled with acidic water and covers 23 acres. It is located about 750 feet uphill from Clear Lake. The Elem Tribal Colony of Pomo Indians lives right next to the mine. There is also a freshwater wetland nearby. Important habitats for three endangered species—the peregrine falcon, southern bald eagle, and yellow-billed cuckoo—are less than a quarter-mile away.

The EPA believes the mine site is causing mercury pollution in Clear Lake. However, the Bradley Mining Company, the current owner, disagrees.

EPA Involvement

In 1976, scientists accidentally found high levels of mercury in fish from Clear Lake. Over the next ten years, state and federal agencies tested the lake and mine. This led the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) to add Sulphur Bank Mercury Mine to the National Priorities List (NPL) in 1990. This list identifies the most polluted sites in the country.

The Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry also looked at the site. They concluded that Sulphur Bank Mine was a public health hazard. (You can learn more about this at Mercury poisoning.)

In 1990, the EPA began studying the flooded pit, waste rock piles, and lake sediments. In 1992, the EPA did an emergency cleanup. They cut back the mine waste along the shoreline, covered it with clean soil, and replanted the area. The agency said that over 32 acres of waste rock had been dumped into the lake and piled along the shore.

Other EPA cleanup actions included building an earthen dam in 1996 to separate the acidic Herman pit from the lake. In 1999, a 4,000-foot pipeline was built to move surface water away from the pit. In 1997, contaminated soil was removed from the nearby Elem Indian Colony.

Legal Actions and Studies

In 1992, the Bradley Mining Co. challenged the EPA's decision to list the mine on the NPL. They argued that the EPA couldn't prove the mercury in the lake came from the mine. The court, however, sided with the EPA. They said there was enough evidence that mercury was being released from the mine.

Researchers from UC Davis have studied the lake. Their tests from 1992 to 1998 showed higher mercury levels closer to the mine. They believe that acidic water from the mine is seeping through the waste rock and into the lake. The Herman pit has a very low pH level of 3.2, meaning it is very acidic.

It's hard to study how water flows through the mine's waste. The old mining operations mixed up the ground, making it difficult to track water and air movement.

UC Davis studies used special tracers to track water flow from the Herman Pit to the lake. They confirmed that water from the pit flows into Clear Lake. However, they couldn't say exactly how much water or the exact path it takes.

Another idea is that geothermal hot springs are a natural source of mercury in Clear Lake. Deep samples from the 1980s show high mercury levels from ancient times. This suggests that natural processes like volcanoes might have released mercury into the lake long ago.

EPA-funded research by UC Davis found that total mercury levels in the lake sediments have not gone down much, even a decade after the cleanup work in 1992.

Cleanup Plans and Costs

In 2005, the EPA placed a lien on 554 acres of Bradley-owned land at the mine site. This was to get back cleanup costs, which were estimated at $27 million. Future cleanup costs could go as high as $40 million.

Another $1.7 million was agreed upon in a deal between the EPA and NEC Acquisition Company. This was for the costs of re-closing three geothermal wells at Sulphur Bank. These wells were drilled in the 1960s to look for geothermal energy, but the project was stopped in the 1980s.

A project manager for the Superfund site said in 2009 that a big problem is dealing with the water in the Herman Pit. They need a treatment plant to stop the flow of contaminated water. The question of where to discharge the treated water is still unsolved. Building a treatment plant and removing all the mine waste could cost between $30 million and $40 million.

Some scientists suggest using phytoremediation for cleanup. This means using special plants, some of which are genetically modified, to absorb mercury and arsenic from the soil. Another less expensive idea is to add things like compost, lime, and fertilizer to the soil. This helps the soil hold onto metals, making them less harmful, and helps plants grow to prevent erosion.

Recovery Act Funds

In 2009, the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act provided $5 million for cleanup work at Sulphur Bank Mine. These funds paid for fixing BIA 120, a road to the Elem Indian Colony. This road was built in the 1970s using mine waste from Sulphur Bank.

The mine waste was also used by a company called Aggrelite in the 1950s. They had a concrete block plant at Sulphur Bank Mine and used the waste to make bricks.

Important People and Discoveries

The Sulphur Bank Mercury Mine has been connected to many interesting people and scientific ideas.

John Veatch

The first person to name the Sulphur Bank in 1856 was John Allen Veatch. He was a doctor, land surveyor, and mineralogist. He came to California during the 1849 California Gold Rush. He later started the first borax mine in the United States.

Veatch described the Sulphur Bank as a "white hill" that was mostly sulfur. He saw hot vapors and sulfur fumes coming out of cracks in the ground.

Chinese Mine Workers

The 1880 Census showed more than 218 Chinese mine workers at Sulphur Bank Mine. Chinese workers were commonly hired for underground mining in California.

There was a lot of disagreement about Chinese workers. Some people felt they were unfair competition because mine owners could hire them for less money.

A famous court case happened in 1880. California passed a law trying to stop Chinese people from working for wages. Most mine owners fired their Chinese workers, but the Sulphur Bank Quicksilver Mining Company did not. Tiburcio Parrott was arrested for not following the law. He then sued California in federal court. The court ruled in Parrott's favor, saying that only the federal government could make rules about international treaties. The Burlingame Treaty of 1868 allowed Chinese people to immigrate and work in America. This court victory meant the Chinese miners at Sulphur Bank could keep their jobs.

Geology of the Mine

When geologist George F. Becker explored the Sulphur Bank Mercury Mine in 1887, he noticed a strong smell of hydrogen sulfide. He described the mine as a "labyrinth of deep, open pits and trenches."

Becker found many interesting things about the mine. His theories made the site famous worldwide. He wrote a book called The Geology of the Quicksilver Resources of the Pacific Slope in 1888.

Oxland's Theory

Becker wanted to test the ideas of Robert Oxland, a doctor and mineralogist. Oxland believed that the cinnabar (mercury ore) at Sulphur Bank was formed by hot springs. He thought hot springs brought metals from deep underground to the surface. Oxland also believed that the cinnabar deposit was still forming.

Becker eventually agreed with Oxland's theory. He tried to solve other mysteries about the mine, like how sulfur got to the surface. He also wondered why the sulfuric acid didn't dissolve the mercury.

Becker was puzzled because the water in the flooded mine shaft had no mercury. He compared Sulphur Bank to hot springs in Nevada that did contain mercury. He thought that ammonia in the water at Sulphur Bank might prevent mercury from being in the water.

Hot Springs and Mercury

Today, geologists believe a large body of magma (molten rock) is located about 8 miles below southern Lake County. This magma feeds the Geysers geothermal field and many abandoned mercury mines, including Sulphur Bank.

All the mercury mines in the area were connected to mineral or hot springs and were near the start of creeks. This includes Sulphur Bank and the Abbott-Turkey Run mines.

Becker also noted that the abandoned Manhattan mercury mine had cinnabar and even gold. This observation caught the attention of mining geologist Donald Gustafson years later.

McLaughlin Mine and Gold

Between 1985 and 2002, the McLaughlin Mine recovered about 3.4 million ounces of gold from the site of the Manhattan and Redington mines. This was the biggest gold discovery in California in the 20th century. It showed how hot springs can create valuable metal deposits.

The site is now the Sylvia and Donald McLaughlin Ecological Preserve. Scientists there study if wetlands can filter heavy metals from mining. Even though it was known for being environmentally careful, the McLaughlin Mine released a lot of mercury in its last year of operation.

Mercury from Hot Springs

The EPA has mostly focused on mining activity at Sulphur Bank as the cause of mercury pollution in Clear Lake. However, other researchers are starting to think that natural geothermal hot springs might play a bigger role in mercury pollution than previously thought.

Scientists have found that natural hot springs add a lot of mercury to Cache Creek, which then flows downstream. Mercury is also found in hot springs and geysers in places like Yellowstone National Park and Calistoga.

Researchers from UC Davis, funded by the EPA, found no mercury in the acidic Herman Pit pond. This is similar to Becker's observation from 1887.

|

| Emma Amos |

| Edward Mitchell Bannister |

| Larry D. Alexander |

| Ernie Barnes |