Woodland period facts for kids

The Woodland period was a long stretch of time in North American history, lasting from about 1000 years before the Common Era (BCE) until Europeans arrived in the eastern parts of the continent. Some experts see the Mississippian period (from 1000 CE until European contact) as a separate time. The name "Woodland Period" was created in the 1930s to describe ancient sites that fit between the Archaic hunter-gatherer groups and the farming Mississippian cultures. This period covers a large area, including what is now eastern Canada (south of the cold Subarctic region), the Eastern United States, and down to the Gulf of Mexico.

This time is seen as a period of steady growth, not sudden big changes. People continuously improved their tools made from stone and bone, learned more about working with leather and making textiles, started cultivating plants, and built better shelters. Many Woodland people used spears and atlatls (spear throwers) for a long time. Later in the period, these were replaced by bows and arrows. In the Southeast, some Woodland groups also used blowguns.

A major change during the Woodland period was the widespread use of pottery. Even though some pottery was made earlier in the Archaic period, it became much more common now, with many different shapes, decorations, and ways of making it. People also started growing more plants, especially a group of native plants called the Eastern Agricultural Complex. This meant that groups moved around less and, in some places, people began living in permanent villages and even cities. More intense farming became a key feature of the Mississippian period, which followed the Woodland period.

Contents

Early Woodland Period (1000–200 BCE)

The Early Woodland period continued many practices from the earlier Archaic times. These included building large mounds, having special burial sites for different regions, and trading interesting goods across a huge part of North America. People still gathered wild foods and started growing some domesticated plants. They often moved in small groups to find food that was available at different times of the year, like nuts, fish, shellfish, and wild plants.

Pottery, which had been made in small amounts during the Archaic period, became very common across the Eastern Interior, the Southeast, and the Northeast. In the far Northeast, the Sub-Arctic, and the Northwest/Plains regions, pottery became widely used a bit later, around 200 BCE.

Trade and Connections

The Adena culture was known for building cone-shaped mounds. Inside these mounds, they buried people, sometimes after cremation, along with valuable items. These items included copper bracelets, beads, and special plates, art made from shiny mica, and other stones, shell beads, and leaf-shaped "cache blades."

The Adena culture is thought to have been central to the Meadowood Interaction Sphere. This was a network where cultures in the Great Lakes, St. Lawrence, Far Northeast, and Atlantic regions traded and connected. We know this because Adena-style mounds and exotic goods from other parts of this network have been found in many places.

Pottery Making

Pottery was made widely and sometimes traded, especially in the Eastern Interior. Clay for pots was usually mixed with crushed rock or limestone to make it stronger. Pots were often shaped like cones or jars with rounded bottoms, slightly narrow necks, and wide rims.

Pottery was often decorated with patterns made by pressing tools into the wet clay. These patterns could look like teeth, wavy lines, checks, or fabric. Some pots had geometric designs carved into them, and very rarely, pictures of faces. Pots were made by hand, by coiling clay and then shaping it with a paddle, without using a fast spinning wheel. Some were painted with red clay.

For a long time, pottery, farming, and permanent settlements were thought to be the three main signs of the Woodland period. However, we now know that in some parts of North America, groups with Archaic ways of life were making pottery without growing crops. In fact, hunting and gathering continued to be the main way people got food. Farming did not become common in much of the Southeast until thousands of years after pottery appeared. In parts of the Northeast, farming was never practiced.

This research showed that some early pottery, made with plant fibers mixed in, appeared around 2500 BCE in parts of Florida (with the Orange culture) and Georgia (with the Stallings culture). But these early sites were still typical Archaic settlements, just with basic ceramic technology.

Because of this, experts are now redefining the Woodland period. It begins not just with pottery, but also with the appearance of permanent settlements, special burial practices, serious gathering or growing of starchy seed plants (like those in the Eastern Agricultural Complex), differences in social groups, and specialized activities. Most of these signs are clear in the Southeastern Woodlands by 1000 BCE.

Food and Lifestyle

In areas near the coast, many settlements were close to the ocean, often near salt marshes, which were full of food. People also tended to live along rivers and lakes in both coastal and inland areas to easily get food. Large amounts of nuts, like hickory and acorns, were processed. Many wild berries, including palm berries, blueberries, raspberries, and strawberries, were eaten, as well as wild grapes and persimmon.

Most groups hunted many white-tailed deer, but they also hunted other small and large animals like beaver, raccoon, and bear. Shellfish were a very important part of their diet, as shown by the many piles of shells found along the coast and inland rivers.

Coastal people moved with the seasons. They would go to the coast in the summer to find sea animals and shellfish, then move inland in the winter to hunt deer and bear, and catch anadromous fish like salmon, which helped them survive the cold months. Inland groups also moved strategically among areas rich in resources.

Recently, more evidence shows that Woodland people relied more on growing plants during this period, at least in some places, than was previously thought. This is especially true for the Middle Woodland period. Experts like C. Margaret Scarry say that "in the Woodland periods, people diversified their use of plant foods... they increased their consumption of starchy foods. They did so, however, by cultivating starchy seeds rather than by gathering more acorns."

Middle Woodland Period (200 BCE – 500 CE)

The start of the Middle Woodland period saw people moving their settlements more towards the interior of the land. As the Woodland period went on, local and long-distance trade of special materials grew a lot. This created a trade network that covered most of the Eastern Woodlands.

Throughout the Southeast and north of the Ohio River, burial mounds for important people became very detailed. These mounds contained many gifts, and many of these items came from far away. Traded materials included copper from Lake Superior, silver from Lake Superior and Ontario, shiny galena from Missouri and Illinois, mica from the southern Appalachians, and special chert stone from Ohio, Indiana, and Illinois. Other items were pipestone from Ohio and Illinois, alligator teeth from the lower Mississippi Valley, marine shells (especially whelks) from the south Atlantic and Gulf coasts, Knife River chalcedony from North Dakota, and obsidian from Yellowstone in Wyoming.

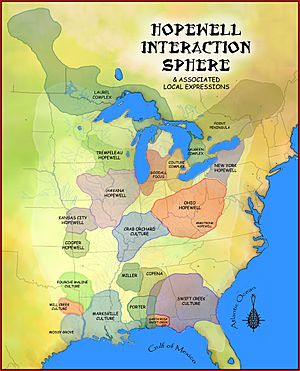

The most famous burial sites from this time are in Illinois and Ohio. These are known as the Hopewell tradition. Because the earthworks (large mounds and shapes made from earth) and burial goods were so similar, experts believe there was a shared set of religious practices and cultural connections across the whole region. This is called the "Hopewellian Interaction Sphere."

These similarities could also be from trading relationships between local clans that controlled certain areas. Access to food or resources outside a clan's territory would be possible through agreements with neighbors. Clan leaders might be buried with goods received from their trading partners to show the relationships they had built. This could have led to permanent settlements, more farming, and a larger population.

Pottery during this time was thinner and better made than before. Examples also show that pottery was more decorated than in the Early Woodland period. One style was the Trempealeau phase, which might have been seen by the Hopewell in Indiana. This type had a round body and lines of decoration with cross-etching on the rim. The Havana style, found in Illinois, had a decorated neck. A major tool unique to this era was Snyders Points. These were quite large and had notches on the corners. They were made by carefully shaping stone with a soft hammer, and then finished by pressure flaking.

Even though many Middle Woodland cultures are called "Hopewellian" and shared ceremonial practices, archaeologists have found that distinct cultures developed during this time. Examples include the Armstrong culture, Copena culture, Crab Orchard culture, Fourche Maline culture, the Goodall Focus, the Havana Hopewell culture, the Kansas City Hopewell, the Marksville culture, and the Swift Creek culture.

Late Woodland Period (500–1000 CE)

The Late Woodland period saw people spreading out more, though the total population didn't seem to decrease. In most areas, the building of burial mounds greatly reduced, as did long-distance trade of special materials. At the same time, bow and arrow technology slowly replaced the use of the spear and atlatl. Also, farming of the "Three Sisters" (maize (corn), beans, and squash) began. While full-scale intensive farming didn't start until the next Mississippian period, this serious cultivation greatly added to the food gathered from wild plants.

Late Woodland settlements became more numerous, but most were smaller than those in the Middle Woodland period. The reasons for this are not fully known. Some experts think populations grew so much that trade alone couldn't support communities, leading some groups to raid others for resources. Another idea is that bows and arrows were so good at hunting that they reduced the number of large game animals. This might have forced tribes to break into smaller groups to better use local resources, which then limited trade between groups. A third possibility is that a colder climate, possibly affected by Northern Hemisphere extreme weather events of 535–536, reduced food yields, also limiting trade. Finally, it could be that farming technology became so good that different clans grew similar crops, reducing the need for trade.

As communities became more separated, they started to develop in their own unique ways. This led to smaller cultures that were special to their regional areas. Examples include the Baytown, Troyville and Coles Creek cultures of Louisiana, the Alachua and Weeden Island cultures of Florida, and the Plum Bayou culture of Arkansas and Missouri.

Although the Late Woodland period traditionally ends around 1000 CE, many regions in the Eastern Woodlands adopted the full Mississippian culture much later. Some groups in the north and northeast of the current United States, like the Iroquois, kept a way of life similar to the Late Woodland period until Europeans arrived. Also, even though bows and arrows became common, people in a few areas never made the change. When Hernando de Soto traveled through the Southeastern Woodlands around 1543, the groups at the mouth of the Mississippi River still preferred using spears.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Cronología de las culturas constructoras de montículos en Norteamérica para niños

In Spanish: Cronología de las culturas constructoras de montículos en Norteamérica para niños

| Georgia Louise Harris Brown |

| Julian Abele |

| Norma Merrick Sklarek |

| William Sidney Pittman |