Volcanic winter of 536 facts for kids

The volcanic winter of 536 was a time when the Earth got much colder. It was the most serious and longest period of cold weather in the Northern Hemisphere (the top half of the world) in the last 2,000 years. This "volcanic winter" happened because at least three volcanoes erupted at the same time. We don't know exactly where they were, but they could have been on different continents.

Most of what we know about this cold period comes from writers in Constantinople. This city was the capital of the Eastern Roman Empire. But the cold weather affected places far beyond Europe. Scientists today believe that in early 536 AD (or maybe late 535), a huge volcanic eruption happened. This eruption sent a lot of tiny particles called sulfate aerosols into the air. These particles blocked sunlight from reaching Earth, making the atmosphere much colder for several years. By March 536, people in Constantinople saw dark skies and felt lower temperatures.

Summer temperatures in Europe in 536 dropped by about 2.5 °C (4.5 °F) below what was normal. The cold from the 536 volcanic winter got even worse in 539–540. Another volcanic eruption caused summer temperatures in Europe to fall by about 2.7 °C (4.9 °F) below normal. There's also proof of another eruption in 547, which would have kept the cold going. These volcanic eruptions led to crops failing, meaning less food. This period also saw the start of the Plague of Justinian, a terrible disease, and a time of hunger. Millions of people died. This cold period started what is called the Late Antique Little Ice Age, which lasted from 536 to 560 AD.

A historian named Michael McCormick said that 536 "was the beginning of one of the worst periods to be alive, if not the worst year."

Contents

What People Saw and Wrote

Many people from that time wrote about the strange weather.

Roman Historians' Accounts

The Roman historian Procopius wrote in 536 AD about the wars with the Vandals. He said, "during this year a most dread strange sign took place. For the sun gave forth its light without brightness... and it seemed exceedingly like the sun in eclipse, for the beams it shed were not clear." He meant the sun looked dim, like during an eclipse.

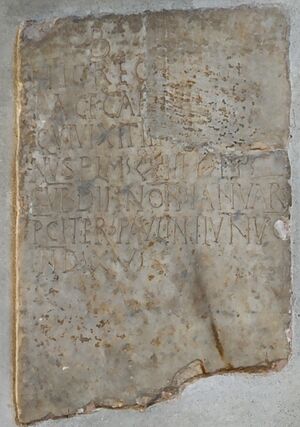

In 538, a Roman leader named Cassiodorus wrote a letter describing the weather:

- The sun's rays were weak and looked "bluish."

- At noon, people didn't cast shadows on the ground.

- The sun felt very weak and didn't give much heat.

- Even a full moon looked "empty of splendour."

- He described "A winter without storms, a spring without mildness, and a summer without heat."

- There was long-lasting frost and unusual dry weather.

- The seasons seemed "all jumbled up together."

- The sky looked "blended with alien elements," like it was always cloudy. It was "stretched like a hide across the sky," blocking the true colors of the sun and moon, and the sun's warmth.

- Frosts happened during harvest time, making apples hard and grapes sour.

- People had to use their stored food to survive.

- Later letters from Cassiodorus talked about plans to help with a widespread hunger.

Other Ancient Writings

The Book of Kings, an old Mandaean text from the early 600s, talks about the years 535–536. It says that grain was so rare, you couldn't find it even if you offered a lot of gold. This shows how little food there was.

Michael the Syrian (who lived much later, from 1126–1199) was a leader of the Syriac Orthodox Church. He reported that from 536–537, the sun shone weakly for a year and a half.

Old Irish writings, called the Irish Annals, also recorded problems:

- "A failure of bread in AD 536" – from the Annals of Ulster

- "A failure of bread from AD 536–539" – from the Annals of Inisfallen

The Annales Cambriae, a text from the mid-900s, mentions for the year 537:

- "The Battle of Camlann, in which Arthur and Medraut fell, and there was great mortality in Britain and Ireland." This suggests many people died.

Chinese Records

Chinese historical books also describe this time:

- The Annals of the Tang Dynasty mention a "great cold" and "famine" in 536.

- The Book of the Later Han talks about a "year of great cold" and "famine that occurred in the summer."

- The Zizhi Tongjian, another history book, also notes the "great cold" and "famine in the summer."

- The Nanshi (History of the South) describes "a yellow ash-like substance from the sky."

Other Strange Events

Other independent reports from that time also mention:

- Very low temperatures, even snow in summer. Snow reportedly fell in August in China, which delayed the harvest.

- Widespread crop failures, meaning not enough food.

- A "dense, dry fog" seen in the Middle East, China, and Europe.

- A drought in Peru, which affected the Moche culture.

Scientific Clues

Scientists have found other ways to learn about this period.

Tree Rings and Ice Cores

By looking at tree rings, scientists can see how much trees grew each year. A scientist named Mike Baillie from Queen's University of Belfast studied Irish oak trees. He found that in 536, the trees grew very little. There was another big drop in growth in 542, after a small recovery.

Ice cores are long samples of ice drilled from places like Greenland and Antarctica. These ice cores show layers of sulfate deposits around 534 AD. These deposits are strong proof of a large cloud of acidic dust in the air. This dust would have blocked sunlight.

What Caused It?

At first, scientists thought the climate changes in 536 AD were caused by either volcanic eruptions (a "volcanic winter") or impact events (like a meteorite or comet hitting Earth).

Volcanic Eruptions

In 2015, scientists re-examined the timelines of polar ice cores. They found that sulfate deposits and a hidden layer of volcanic ash (called a cryptotephra layer) were from exactly 536 AD. Before this, they thought it was from 529 AD. This new dating strongly suggests that a huge volcanic eruption caused the dimming of the sun and the cooling. This makes it less likely that something from space caused it, though a space impact around that time can't be completely ruled out.

Scientists are still trying to find the exact volcano that erupted. Several volcanoes were suggested, but then ruled out:

- Some thought it was Rabaul caldera in Papua New Guinea. But new dating shows that eruption happened much later, between 667 and 699 AD.

- David Keys suggested Krakatoa. He thought a big eruption recorded in an old Javanese book from 416 AD actually happened in 535 AD. But drilling in the Sunda Strait showed no eruption happened there at that time.

- Robert Dull and his team suggested the huge Tierra Blanca Joven eruption (TBJ) from the Ilopango caldera. But volcanic ash from TBJ found in ice cores dates that eruption to 429–433 AD.

- Christopher Loveluck and his team thought it might be Icelandic volcanoes, based on tiny glass shards from a Swiss glacier. However, the volcanic ash from 536 AD found in ice cores is chemically different from Icelandic ash. Also, the dating of the shards in the Swiss glacier is not very precise.

Newer chemical tests of the volcanic ash from 536 AD show at least three eruptions happened at the same time in North America. One of these eruptions is linked to widespread ash from the Mono–Inyo Craters in California. The other two eruptions likely came from the Aleutian Arc (islands near Alaska) and the Northern Cordilleran Volcanic Province (in western Canada and Alaska).

What Happened Next?

The cold period of 536 and the hunger that followed might explain why rich people in Scandinavia buried large amounts of gold at the end of the Migration Period. They might have been sacrificing the gold to please the gods and bring back the sunlight. Old Norse myths like the Fimbulwinter (a long, harsh winter) and Ragnarök (the end of the world) might be based on the memory of this event.

A book by David Keys suggests that these climate changes led to many big events. These include the start of the Plague of Justinian (541–549), the decline of the Avars, and the movement of Mongol tribes. He also links it to the end of the Sassanid Empire, the fall of the Gupta Empire, the rise of Islam, and the expansion of Turkic tribes. Keys also suggests it caused the fall of Teotihuacán, a big city in ancient Mexico. A TV show called Catastrophe! How the World Changed was made based on Keys' book.

However, many historians and scientists don't fully agree with Keys' ideas. A British archaeologist named Ken Dark reviewed Keys' book. He said that "much of the apparent evidence presented in the book is highly debatable, based on poor sources or simply incorrect." But he also noted that the book was important for looking at global changes in the 6th century. He felt it didn't fully prove its main idea.

A language expert named Andrew Breeze wrote a book in 2020. He argues that some events about King Arthur, like the Battle of Camlann, were real. He thinks they happened in 537 because of the hunger caused by the climate change in 536.

Historian Robert Bruton believes this disaster played a part in the decline of the Roman Empire.

See also

- 1257 Samalas eruption

- 1452/1453 mystery eruption

- 1815 eruption of Mount Tambora, the largest ever recorded

- 946 eruption of Paektu Mountain

- Fimbulvetr

- Great Famine of 1315–1317

- Justinian I, Roman emperor at the time

- Laki

- Minoan eruption

- Tierra Blanca Joven eruption

- Volcanism of Iceland

- Year Without a Summer, 1816

| Bayard Rustin |

| Jeannette Carter |

| Jeremiah A. Brown |