Brooks–Baxter War facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Brooks—Baxter War |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Reconstruction Period in Arkansas | |||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Baxter administration “Minstrel” Republicans |

Republican opposition “Brindle-tail” Republicans |

||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| ~2,000 militia | ~1,000 militia | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| ~200 dead | |||||||

The Brooks–Baxter War, also called the Brooks–Baxter Affair, was a fight for control of the state of Arkansas. It happened during the Reconstruction Period after the American Civil War. Joseph Brooks tried to take over as governor from Elisha Baxter. Both men were Republicans, but they belonged to different groups within the party.

Baxter's group was called the "Minstrels." They were mostly "carpetbaggers," meaning Northerners who moved South after the war. Brooks's group was called the "Brindle-tails." They were mostly "scalawags," meaning Southerners who supported the Union, and also included "freedmen" (formerly enslaved people). In the end, Baxter won, and his government was put back in charge.

This conflict began after the 1868 Arkansas Constitution was approved. This new constitution allowed Arkansas to rejoin the United States. The Reconstruction Acts required Southern states to accept the 14th Amendment. This amendment gave civil rights to freedmen. It also meant new state constitutions had to give freedmen the right to vote. At the same time, many former Confederates temporarily lost their voting rights.

Some conservatives and Democrats refused to join in writing the new constitution. They also stopped taking part in the government. Republicans and Union supporters worked together to write and pass the new constitution. They then formed a new state government. However, violence from groups like the Ku Klux Klan and a struggling economy caused problems. The Republican group soon split into the "Minstrels" and "Brindle-tails."

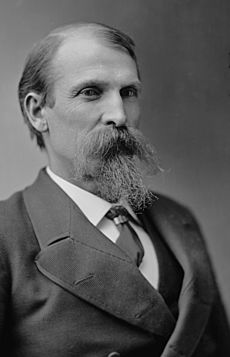

The 1872 election for governor was very close. Minstrel Elisha Baxter won over Brindle-tail Joseph Brooks. But there were many reports of cheating and threats during the election. Brooks challenged the results in court. At first, he didn't succeed. However, Baxter upset many of his supporters by giving former Confederates back their voting rights. In 1874, a county judge declared Brooks the winner, saying the election was dishonest. Brooks then took control of the government by force. But Baxter refused to give up.

Each side had its own militia (citizen army), made up of several hundred men. Many bloody fights broke out between the two groups. Finally, U.S. President Ulysses S. Grant stepped in. He supported Baxter, which brought the conflict to an end. This war, along with a new Arkansas Constitution of 1874, marked the end of Reconstruction in Arkansas. The Republican Party in the state became much weaker. Democrats took power and controlled the governorship for the next 90 years.

Contents

Why the War Started: The Background

Arkansas's New Constitution of 1868

After the American Civil War, Southern states like Arkansas were in chaos. Slavery, which was central to their way of life, was gone. People from the North, called 'carpetbaggers' by Southerners, came to help rebuild. In 1866, the U.S. Congress worried about what was happening in the Southern states. Former Confederate leaders were being re-elected. Southern states passed "Black Codes" that limited the rights of former slaves. Violence against Black people was also common.

To fix this, Congress passed the Reconstruction Acts of 1867. These laws broke up the old state governments. They divided the South into military districts. Southern states could only rejoin the Union if they wrote new constitutions. These constitutions had to give civil rights to freedmen. They also had to accept the 14th Amendment.

In late 1867, Arkansans voted to create a new constitution. Delegates met in Little Rock in January 1868. A group of white Union supporters, freedmen, and carpetbagger Republicans worked together. They agreed on most important ideas. Key leaders included James Hinds, Joseph Brooks, John McClure, and Powell Clayton.

The new constitution gave the right to vote (suffrage) to all adult Black men. It also changed how legislative districts were set up. This was to reflect that freedmen were now full citizens. The state government gained more power. It created the first public school system for both Black and white children. It also set up welfare programs that were needed after the war. The governor was given strong powers. He could appoint top state officials, like Supreme Court Judges, without legislative approval. The governor also led many state organizations. The constitution also temporarily took away voting rights from former Confederate Army officers. It also affected anyone who refused to promise loyalty to the idea of equal rights for all people.

The Democratic Party in Arkansas was also in disarray in 1867–68. One main idea for Democrats was white supremacy. They also resisted Black people getting the right to vote. At their state meeting in January 1868, Democrats said they wanted to unite "the opponents of negro suffrage and domination." Some party leaders wanted military rule to continue. They thought this was better than allowing freedmen full civil rights, including voting. More traditional Democrats were not interested in the new constitution. They stayed loyal to the ideas of the Confederacy. Many chose not to vote in elections. They said the new constitution was unfair because it took away their voting rights. It also gave voting rights to freedmen, whom they considered inferior. They also angered freedmen, who were now the largest group of voters. They passed resolutions against them. Their first resolution said they wanted a "White Man's Government in a White Man's country." Only about half of registered voters cast ballots in April 1868. Two-thirds of those who voted approved the new constitution.

Governor Powell Clayton's Time in Office

Powell Clayton, a 35-year-old former Union army general, became governor as a Republican in April 1868. He had stayed in Arkansas after marrying a local woman. The election had many problems. For example, in Pulaski County, more votes were counted than there were registered voters. Also, election officials admitted they gave ballots to voters from other counties. Both sides claimed there was cheating and threats. Armed groups were even stationed on roads to keep voters from voting.

In July 1868, Arkansas rejoined the Union, and Clayton became governor. The new state assembly had already started meeting in April. But they couldn't do much until the state was officially back in the Union. The previous governor, Isaac Murphy, was not recognized by the federal government. But he continued to act as governor during this time. Both Clayton and Murphy managed to get paid as governor at the same time. When Clayton took office, he gave many important Republican politicians jobs in the new state government. However, he did not find a place for Joseph Brooks.

Brooks and Clayton had been rivals even before the 1868 election. Clayton saw Brooks as a strong competitor. He didn't want Brooks to become too powerful in the party. Brooks felt his hard work for the party wasn't recognized. He became angry and resentful of other Republicans, including Clayton.

Democrats in the state called themselves "the Conservatives." They were very angry that freedmen—former slaves—were not only free but also full citizens with civil rights. Worst of all, in their view, freedmen were allowed to vote. Even though freedmen could vote, former Confederate officers could not. This was especially frustrating because they had to pay taxes for new projects but couldn't vote against them. They even saw this as an attempt by the Republicans to go against God's will.

Violence quickly spread across the state. Former Confederate Army officers in Memphis, Tennessee, formed the Ku Klux Klan. This group fought against the new order. The Klan quickly spread into Arkansas. Republican officials, like Congressman James Hinds, were attacked. Black citizens trying to use their new civil rights were also attacked. Hinds and Brooks were ambushed by gunmen while traveling. Brooks was badly hurt, and Hinds was killed. Hinds was the first sitting member of Congress ever to be killed. His death caused national outrage over the political violence in the South. A local Democratic official and suspected Klansman was identified as the killer. Most people at the time blamed the Klan. No one was ever arrested for the murder. As more violence spread, Clayton declared martial law in 14 counties.

Many Democratic newspapers denied the Ku Klux Klan existed. But they still reported on the violence. Later research shows the Klan was responsible for most of the violence. A state militia was formed to stop the violence. But it was not well-equipped. With no uniforms and poor weapons, the militia was often mistaken for groups of robbers. This led to a brief but remembered "Militia War." It caused fear throughout the state.

Clayton feared he couldn't ensure fair elections. So, he canceled fall elections in counties where political violence had broken out. This further reduced the Democratic vote. As a result, Arkansas supported President Grant, the Republican candidate. This happened even though most of the population was Democratic.

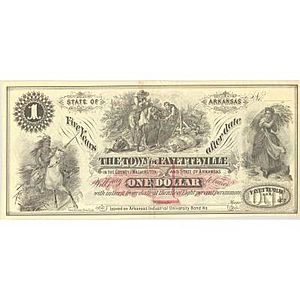

Paying for New State Projects

Clayton used different ways to pay for needed projects in the state. Most of the South desperately needed new roads, bridges, and other improvements. He raised taxes and tried to improve the state's bad credit. He did this by repaying old debts and issuing new ones. He also flooded the state with paper scrip (money substitutes). All these methods failed and increased the state's debt.

Raising more taxes was very unpopular with both Democrats and Republicans. People in the state were generally not wealthy. New bonds (loans) caused arguments and scandals in the government. Many bonds were issued for roads and railroads that were never built. Or they were built and then torn up and rebuilt elsewhere. Some projects even received money from different bonds for the same work. For example, money was given for railroad embankments and also for roads in the same place. One very controversial bond involved buying slate for a state prison roof. But the slate was used to build a mansion for a Republican official, J. L. Hodges. He later went to jail for this.

Promissory notes, or scrip, were issued to raise money. This money was used for construction and public projects. However, the new constitution said the state's credit could not be loaned without voters' permission. This made these notes illegal. Their introduction also caused real money to disappear from circulation.

The Republican state projects included levees (walls to hold back water) and railroads. Arkansas's first public school system was created. The government also started Arkansas Industrial University, which became the University of Arkansas. They also established the Arkansas School for the Deaf and the Arkansas School for the Blind. However, the state's debt grew a lot. The state had extra money when Clayton took office. But by the end of his term, the state debt had grown to $5 million.

Minstrels and Brindle-tails: The Republican Split

The 'scalawag' (native conservative Republicans) and 'carpetbagger' (migrant radical Republicans) groups had worked together. They gained full control of the state in 1868. But once they had power, the carpetbaggers' high spending caused problems between the two groups. The party split into factions. There was strong opposition to the Clayton government's questionable money dealings. Despite attempts to make peace, the Arkansas Republican Party publicly split in two. 'Scalawags' began to criticize the carpetbaggers' careless spending.

The scalawags held a meeting and called themselves the "Liberal Republicans." They supported ideas like universal forgiveness for former Confederates, voting rights for everyone, economic changes, and an end to what they called the "Clayton dictatorship." A small group of Clayton supporters, unhappy with the government's spending, also joined this group. Joseph Brooks was among them. He claimed to be the original Radical Republican in Arkansas and became their natural leader. Brooks was a Northern Methodist preacher. He had been a chaplain in the Union army. He was known for his powerful speeches that mixed politics and religion. He had led the 1868 Republican state meeting. At this time, he was a State Senator. Even though he had been involved with the carpetbaggers from the start, Clayton had not given him a government job. Clayton saw Brooks as a possible rival.

Clayton's supporters started calling the new group the Brindle-tails. This name came from Jack Agery, a Black contractor and speaker who supported Clayton. He said Brooks reminded him of a "brindle-tailed bull" that scared other cattle. Clayton's supporters then mockingly called Joseph Brooks and his followers Brindle-tails. This name stuck. The Brindle-tails wanted a new constitution. It would give voting rights back to former Confederates. This idea appealed to Democrats and pre-war Whigs. They started gaining support among those who couldn't vote and the Liberal Republicans.

The Brindle-tails, in turn, mockingly called the carpetbaggers and Clayton's Republicans the Minstrels. This name also stuck. It likely came from John G. Price, editor of the Little Rock Republican and a strong Clayton supporter. Price was a good musician and comedian. He had even performed in a minstrel show, wearing blackface.

The Brindle-tails desperately wanted Clayton out of the governor's office. Luckily for them, Lieutenant Governor James M. Johnson was a Brindle-tail. So, their plan was to remove Clayton and let Johnson become governor. Clayton knew about their plans. When he briefly left the state for New York, he told no one. Johnson, who was at home far from the capital, found out. He tried to go to the capital to take control and have Clayton arrested. But he arrived too late. Later, after Johnson gave a speech demanding changes, the Minstrels started to target him. In January 1871, they tried to impeach him in the General Assembly. The main charge was that Johnson, as Senate President, had sworn in Joseph Brooks as state senator. He then recognized Brooks in the Senate. This was within his powers as lieutenant governor. But he avoided impeachment by only two votes. The investigation badly hurt his reputation, even though he had done nothing wrong. His political career never recovered.

In 1871, Clayton was accused of changing the results of a U.S. House election. The election was between Thomas Boles and John Edwards. According to Arkansas law, election results were to be certified and given to the secretary of state. Then, the governor and secretary of state would "arrange" the results. The governor would then announce the winner. Boles won the election. But Clayton certified Edwards as the winner. This happened after the State Supreme Court and a legislative investigation. Polls in Pulaski County were taken over by Brindle-tails. They stopped legally appointed Minstrel judges from doing their job. The defeated candidates sued. The State Supreme Court forced the clerk to certify the correct votes. As a result, Brindle-tail delegates from Pulaski County were removed from the state house. Clayton, believing there was cheating, declared Edwards the winner. This was despite the Secretary of State already certifying Boles' victory. Clayton was then accused of breaking a federal law. But it was found that his actions were not illegal. He was not bound by Congress. Under federal law at the time, state governors were not considered election officials. Boles became a congressman.

To remove Clayton from state affairs, the Brindle-tails and Democrats decided to elect him to the U.S. Senate. He won unanimously. But he refused to take his seat. This would have meant Johnson would become governor. In 1871, the state House of Representatives tried to impeach Clayton. They accused him of many things. These included removing officials who were fairly elected, helping with dishonest elections, and taking unfair payments for state railroad bonds. House members even tried to force him out of office. They reportedly locked him in his office and nailed the door shut. But Clayton said they had no right to remove him. At the same time, the House also tried to impeach Chief Justice John McClure. This was for his part in trying to deny Johnson his rights as lieutenant governor.

Two investigations failed to find evidence against Clayton. The legislature refused to continue. All charges were dropped, and Clayton was cleared. He was never found guilty of any wrongdoing as governor. Finally, a deal was made. Johnson, whose political career was damaged, resigned as lieutenant governor. He was appointed Secretary of State. He also received thousands of dollars for his loss of power. A strong Clayton supporter, O. A. Hadley, was then appointed lieutenant governor. Three days later, Clayton left for Washington, D.C., to join the U.S. Senate. Hadley then became governor.

The Democrats' newspaper, the Arkansas Daily Gazette, celebrated: "It will be a source of infinite joy and satisfaction, to the oppressed and long suffering people of Arkansas, to learn that, on yesterday, the tyrant, despot and usurper, late of Kansas, but more recently, governor of Arkansas, took his departure from the city and his hateful presence out of our state, it is to be hoped, forever and ever."

Even though he was no longer a state official, Clayton remained the leader of state Republicans. He still controlled appointments and federal money. He began removing Brindle-tails from federal jobs, including Joseph Brooks, who was an Internal Revenue Assessor.

The 1872 Governor's Election

Republican Party Choices

Minstrels Choose Elisha Baxter

For the 1872 governor's election, the Minstrels chose Elisha Baxter. Baxter was a lawyer, politician, and merchant from North Carolina. He had settled in Batesville. He was a lifelong Whig. He was elected Mayor of Batesville in 1853 and to the state legislature in 1858. When the Civil War began, he was unsure which side to support. When Union General Samuel Curtis occupied Batesville in 1862, he saw Baxter as loyal to the Union. He tried to make him a "Regt. of loyal Arkansians," but Baxter refused. When Curtis left, Baxter had to flee to Missouri. He was captured and brought back to Little Rock. He was accused of treason but escaped before his trial. He wrote about this in his autobiography:

"Through a fortunate combination of circumstances I escaped from prison before my trial came on and lived for eighteen days in the forist(sic) and fields near Little Rock without a morsil(sic) of food except such raw corn and berries as I could gather in my lone wanderings. While a prisoner I felt that I was ungenerously treated by the harsh criticisms of the press and individuals not only in regard to my want of loyalty to the southern caus(sic) but also with regard to my supposed want of courage. I therefore resolved if God would grant me deliverance I would at once enter the Federal Army."

When Baxter returned to Batesville, he formed the 4th Arkansas Mounted Infantry for the Union. He led it until Governor Murphy made him a State Supreme Court judge in 1864. Soon after, the legislature elected him to the U.S. Senate. But he and another man were not allowed to sit in the Senate. This was because the Senate did not recognize the Murphy Administration. In 1867, Governor Clayton appointed him judge of the 3rd Judicial circuit. In 1868, he was appointed to the 1st Congressional district of Arkansas. He held these two jobs until he was nominated for governor in 1872. Baxter was not well-known. He also had no scandals, unlike most Minstrels. They believed he could get votes from Union supporters and Northerners, their main base. He could also attract votes from people born in the state.

Brindle-tails Choose Joseph Brooks

Joseph Brooks ran for governor as the Brindle-tails' candidate. Brooks strongly supported civil rights for former slaves. But he also supported giving voting rights back to former Confederates. This was a common idea among Liberal Republicans across the country. When the Democrats met, they agreed not to run their own candidate. They even decided to support Joseph Brooks. This was as long as the election was fair and legal. Elections in the state had been full of cheating for five years. The issue of giving voting rights back to Confederates was very important in this election.

The Main Election

The 1872 election has been called a "masterpiece of confusion" by historian Michael B. Dougan. He noted, "That carpetbagger Brooks ran with Democratic support against a scalawag nominated by a party composed almost exclusively of carpetbaggers was enough to bewilder most voters as well as the modern student."

Before and after the election, reports of cheating were printed daily in the Gazette. Because communication was slow, messages from other counties often took up to a week. There were many reports of problems at state polling places. Names were strangely removed from voter lists. People voted without proof of registration. The Gazette wrote:

"It would be as great a farce of yesterday's election to designate it otherwise than a fraud. It was one of the worst ever yet perpetrated in the state. The city judges paid no attention to any registration either old or new, but permitted everybody to vote, and in many instances without question. Men were marched from one ward to another and voted early and often."

On November 6, 1872, the day after the election, the Gazette reported: "The election was one of the most quiet in Little Rock we ever witnessed." The results that day were too small to say for sure who had won. The newspaper reported cheating. Rumors spread that voter registration had been cut short or extended in many counties. This was to help whoever controlled the polling places. The following Monday, the Gazette published incomplete counts. These showed a small lead for Baxter. They also reported more attempts at cheating. Some unofficial polling places had been set up. But only votes cast at the regular polls were counted.

By November 15, the Gazette claimed Brooks had won. But by the next day, because of problems and votes that would be thrown out, Baxter was projected to win by only 3,000 votes. The General Assembly met on January 6 for a special session. They declared Baxter the legal winner. He had received the most votes. After a short speech, Chief Justice John McClure swore him in. He then took on the duties of Governor of Arkansas.

Brooks's supporters immediately said the election was dishonest. Democrats, Brindle-tails, and all non-Republican newspapers loudly said the election was fraudulent. They insisted Brooks had actually received the most votes. However, most citizens from both parties accepted the results. Only a minority of Brooks's supporters believed the election was dishonest.

The Fight for the Governorship

Brooks's Legal Challenges

The first person to sue over the election was Judge William M. Harrison. He was on Brooks's ticket. He filed a complaint with the U.S. Circuit Court in Little Rock. He claimed he had a right to a seat on the Supreme Court because of the dishonest election. Brooks's campaign also filed a lawsuit shortly after, on January 7, 1873. Judge H. C. Caldwell heard the Harrison case. He said the Federal Court had no power in the matter and dismissed the case. The decision in Harrison's case also led to Brooks's case being dismissed.

Brooks then asked the General Assembly for a recount. The assembly discussed the matter on April 20, 1873. They voted 63 to 9 not to let Brooks challenge the election. This did not stop Brooks. He then asked the Arkansas Supreme Court for a writ of quo warranto (a legal order to show by what authority a public office is held). He was denied again. They also ruled that state courts had no power in the matter and dismissed the case. They gave a long explanation. They said the General Assembly should decide contested governor elections. This is because they are the directly elected representatives of the people.

It seemed Brooks had tried all legal ways. But on June 16, 1873, he filed another lawsuit against Baxter. This time, it was with the Pulaski County district court. Under Arkansas law, if a person takes an office they are not entitled to, a lawsuit can be started against them. This can be done by the State or by the person who should have the office. On October 8, 1873, Baxter filed a plea saying the court had no power. But he thought the court might decide against him. He sent a telegram to President Grant. He told him about the situation in Arkansas. He asked for federal troops to help him keep the peace. Grant said no to his request.

Baxter and Brooks Change Sides

There were rumors that Joseph McClure, the Chief Justice who swore Baxter into office, planned to have Baxter arrested or killed. This was supposedly because Baxter had replaced W. W. Wilshire, a Minstrel, with Robert C. Newton, a former Confederate, as head of the state militia. U.S. Attorney General Williams contacted Baxter. He suggested Baxter ask for federal troops again. A letter from President Grant followed, offering protection. The Grant administration usually followed Powell Clayton's advice on Arkansas matters. So, it seemed the former governor still supported Baxter. The Republican Party of Arkansas, still controlled by the Minstrel group, issued a statement. It criticized Brooks's attempt to challenge the election. This was published in the Little Rock Republican on October 8, 1873. All major party members, including Clayton, signed it. However, the Minstrels would soon turn against Baxter for not following the party's wishes.

Baxter had been governor for a year. He was now following his own path. He began to undo the systems the Minstrels had put in place. He appointed honest Democrats and Republicans to the Election Commission. He reorganized the militia, putting it under state control, not the governor's. He also pushed for a change to the state constitution. This change would give voting rights back to former Confederates.

On March 3, 1873, the state legislature passed a bill giving voting rights back to former Confederates. This pleased many people in the state. But it worried the Minstrels. The legislature called a special election in November. This was to replace 33 members, mostly Minstrels, who had left for jobs in Baxter's government. Baxter refused to let the Minstrels control the election. He said free, honest elections would happen during his term. With the help of the newly re-enfranchised voters, conservative Democrats won the election. They gained a small majority in the legislature. Baxter was about to lose support from his Republican base.

In March 1874, Baxter rejected the Railroad Steel Bill. This bill was a key part of the Radical Republican Reconstruction plan. It would have freed railroad companies from their debts to the state. It also would have created a tax to pay the interest on the bonds. This was clearly not legal. Baxter's rejection questioned the legality of the 1868 railroad bonds, which created public debt. It is likely the Minstrels made a deal with Brooks to support the railroad bonds. Within a month, the political supporters of Brooks and Baxter began to switch sides. Senator Clayton said that "Brooks was fairly elected in 1872; and kept out of office by fraud." Governor Baxter was now supported by the Brindle-tails, those who wanted voting rights restored, and the Democrats. Brooks was finding support among the Claytonists, Northerners, Unionists, and Minstrels.

Brooks was given three important Minstrel lawyers. After a year, on April 15, 1874, Baxter's objection to Brooks's complaint was suddenly called up. Neither of Baxter's lawyers were in the courtroom. The objection had been submitted without their knowledge. Without letting Baxter testify, Judge Whytock denied the objection. He awarded Brooks $2,000 and the office of Governor of Arkansas. Neither Brooks nor the court told the legislature or Governor Baxter. Judge Wytock then swore in Joseph Brooks as the new governor of Arkansas. He had no authority to do this.

Brindle-tails Take Control

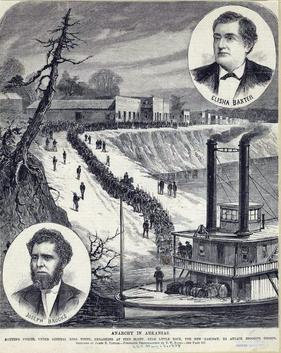

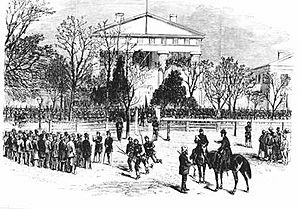

With help from General Robert F. Catterson and the state militia, Brooks, with about 20 armed men, marched to the Arkansas Capitol building. It is now called "the Old Statehouse." They ordered Baxter to leave his office. But Baxter refused unless he was physically forced. The group then dragged Baxter out of the Capitol building and onto the street.

By the end of the afternoon, nearly 300 armed men were on the Capitol lawn. Brooks's men took control of the state arsenal (a place where weapons are stored). They began turning the Statehouse into an armed camp. Telegrams with many signatures were sent to President Ulysses S. Grant. They supported Brooks as the legal governor. Three of the five Supreme Court justices also sent telegrams supporting Brooks. Brooks himself sent a telegram to the President. He asked for access to weapons at the federal arsenal. He also told the press he was the new governor. The state's senators, Clayton and Steven Dorsey, met with President Grant. They sent a message to Brooks giving their support.

It was unusual for someone physically removed from power, but Baxter was allowed to stay free in Pulaski County. He first went to the Anthony House. This was three blocks from the State Capitol. Ads in the Gazette showed the Anthony House continued to operate as a hotel during the crisis. Fighting happened outside the hotel. At least one man, David Fulton Shall, a real estate dealer, was shot dead while standing in a window.

Baxter then moved his headquarters to St. Johns College. This was a Masonic institution on the southeastern edge of the state. Baxter issued two statements to the press from his temporary office. He claimed his right to the governorship by the people's vote and the legislature's decision. Both were printed in the Gazette. He received support from many important Democrats in the city. All of them had initially voted for Brooks. He then sent a message to President Grant explaining the situation. He called Brooks and his group "revolutionaries." He said he would do everything, including armed conflict, to regain control of the state. He asked for the Federal Government's support.

Brooks issued a statement to the people of Arkansas, asking for their support. Baxter replied with a statement declaring martial law in Pulaski County. A company of young men from Little Rock was then formed. On the evening of April 16, this assembled army, now called the "Hallie Riflers," escorted Baxter back to the Anthony House. He set up his headquarters there. From there, he began trying to conduct state business again.

Now, two militias were marching and singing through Little Rock. The city became a battleground. Both forces were commanded by former Confederate soldiers. Former Brigadier-General James F. Fagan led Brooks's men. Robert C. Newton, a former Colonel, led the Hallie Riflers, or Baxter's forces. Baxter's men occupied the downstairs billiards area of the Anthony House. They patrolled the streets outside. Down the street, Brooks's men patrolled the front of the state house. The front line was Main Street. The postmaster handled the situation by only delivering mail addressed to Brooks or Baxter. He held all mail simply addressed to "Governor of Arkansas."

The Lady Baxter, a cannon on display in front of the Old State House, is the most famous item left from the war. It's a Confederate copy of a U.S. Model 1848 64-pounder siege gun. It was designed to fire explosive shells. It came from a foundry in New Orleans. It was brought to Arkansas in 1862 by steamboat. It saw action on the Mississippi, White, and Arkansas rivers. Then it was moved to Fort Hindman at Arkansas Post. Union forces captured the fort in 1863 but left the cannon. Confederates brought it to Little Rock. They placed it on Hanger Hill overlooking the river. It was meant to stop ships coming upstream. But it was never fired in that position. Little Rock was captured in September 1863. Confederates tried to break the cannon. When that failed, they drove a nail into its firing hole and left it on the shore. It sat there half-buried until 1874. Baxter's men pulled the cannon out, repaired it, and renamed it the "Lady Baxter." They made it ready to fire. It was placed behind the Odd Fellows hall, now the Metropolitan Hotel. This was on the corner of Main and Markham streets. It was meant to hit any boats bringing supplies for Brooks up the river. However, the cannon was only fired once. This was a celebratory blast when Baxter finally returned to the governor's seat. The war's last injury was from this cannon firing. The operator was badly hurt. It has been in its current place in front of the old state capitol ever since.

The conflict had echoes of the Civil War and racial tensions. Brooks's men numbered 600 by this time. They were all freedmen who supported Republicans as their liberators. Baxter's forces, all white Democrats, grew steadily during the conflict. They reached nearly 2,000 men. Several bloody fights happened. A small naval battle, known as the Battle of Palarm, broke out on the Arkansas River near Natural Steps. Brooks's men attacked a flatboat called the "Hallie." They thought it was bringing supplies. The shooting lasted about ten to fifteen minutes. Then the pilot raised a white flag, signaling surrender. A stray bullet hit the boat's supply pipe, cutting off its power. The boat drifted downriver, out of gun range, and got stuck on the shore. Reports vary on the exact number of injuries. The boat's captain, a pilot, and one rifleman were killed. The other pilot and three or four riflemen were injured. One report said Brooks's regiment had one man killed and three injured. Another report said five men were killed and "quite a number" injured.

Reports of injuries vary greatly depending on the source. The New York Times on May 30, 1874, gave the following numbers:

| Army | Dead | Wounded |

|---|---|---|

| Baxter militia | 8 | 13 |

| Brooks militia | "about 30" | "upwards of 40" |

Brooks Loses Support

On May 3, men claiming to be Baxter supporters took over a train from Memphis, Tennessee. They arrested federal Court Justices John E. Bennett and Elhanan John Searle. They thought the Court would not be able to make decisions without enough judges. Baxter denied they were acting under his orders. The Judges were taken to Benton, Arkansas. For several days, no one knew where they were. Federal officials began searching for them. Justice Bennett was able to send a letter asking why they were being held. Upon receiving the letter, troops were sent to Benton to get the two Justices. But they had escaped by May 6 and made their way to Little Rock.

In Washington, Brooks had political support. But Baxter also had support because of the unfair way he had been removed from office. President Grant had already dealt with a disputed election in Louisiana, the Colfax massacre. Federal troops had to be sent there to restore order. As Brooks and Baxter fought for support in Washington, D.C., Grant pushed for the dispute to be settled in Arkansas. Baxter demanded the General Assembly meet. He knew he had their support. But so did Brooks. So, Brooks and his men would not let anyone into the capitol building. Brooks, on the other hand, had the support of the district court. He hired Little Rock's top lawyer, U. M. Rose. However, Grant's decision would soon lead to the end of Brooks's time as governor.

It became clear that federal help was needed to settle the dispute. This was despite President Grant's general policy to stay out of Southern states' affairs. The President often expressed frustration with Southern governors. They frequently asked for federal troops to stop election violence. Grant and the United States Attorney General, George Henry Williams, issued a joint statement. They supported Baxter and ordered Brooks to leave the capitol. They also sent the dispute back to the State Legislature.

Historian Allan Nevins believed Grant had been tricked. When Baxter refused to sign two million dollars' worth of dishonest railroad bonds, some powerful figures turned against him. They convinced Grant to do the same.

On May 13, President Grant used the Insurrection Act of 1807. This allowed federal troops to be used for domestic law enforcement.

President Grant on May 15, 1874, had declared Baxter to be governor, denouncing Brooks and his party; now on February 8, 1875, he declared that Brooks had been elected and denounced Baxter and his followers! Senator Dorsey, later a principal in the Star Route frauds, was a neighbor and close friend of Boss Shepherd's, living in a house owned by him. ... "I believe," commented [Secretary of State] Fish, "that there is a large steal in the Arkansas matter, and fear that the President has been led into a grievous error."

On May 11, Governor Baxter asked the General Assembly to meet in a special session. They did. They apparently met "behind Baxter lines," though the exact location is unclear. Since the Speaker of the House and President pro tempore of the Senate were both absent (they were Brooks supporters), they were replaced. J. G. Frierson was elected President pro tempore of the Senate. James H. Berry was elected Speaker of the House. They then passed a law calling for a constitutional convention. Governor Baxter approved this on May 18. The law set an election for the last day of June. It also appointed delegates from Arkansas counties. Two days later, Generals Newton and Fagan agreed to a ceasefire. At the same time, the Arkansas Supreme Court finally heard Brooks's case. They voted three to one in favor of Baxter's election. This further supported Grant's decision and Baxter as governor. The Pulaski County Circuit court also met. They issued a statement saying Judge Wytock had acted alone. His decision did not represent the court. The trial had been unfair to Baxter. The Supreme Court had already ruled that the court had no power under the state constitution. They declared Judge Wytock's decision invalid.

On May 19, General Newton and his troops reoccupied the State House grounds. Brooks's forces had just left. On the 20th, Governor Baxter was reinstated.

What Happened Next

In June 1874, Clayton announced he could no longer control things in Arkansas. He and his friends would agree to any deal that would keep them safe from being accused of crimes. However, the Democrats fought back. They tried to impeach many Minstrels, including Supreme Court Justice John McClure. Clayton finished his Senate term but was not re-elected.

On September 7, 1874, the new constitution was finished and signed by most delegates. All voters, including former Confederates and freedmen, voted. The election was not only to approve the new constitution. It was also to elect state officials if the constitution was approved. The Republicans took the same stance as the Democrats had earlier. Believing the election was illegal, they nominated no candidates. Conservative Democrats and allied groups used threats and violence. They stopped Black people from voting. The new constitution was approved on October 13, 1874. Democratic officials were elected almost completely, including new Democratic Governor Augustus H. Garland. He became governor on November 12, 1874. Baxter left office after serving only two years of a four-year term.

It was a long time after the Brooks–Baxter War before people in Arkansas allowed another Republican to become governor. The next 35 governors of Arkansas, ruling for a total of 90 years, were all Democrats. This changed when Republican Winthrop Rockefeller became governor in 1966. He defeated James D. Johnson. Winthrop became governor while his brother Nelson was governor of New York. The defeat of Johnson in Arkansas and William M. Rainach in Louisiana ended the strong hold of segregation in politics.