Conquest of Majorca facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Conquest of Sa Pobla |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Reconquista | |||||||

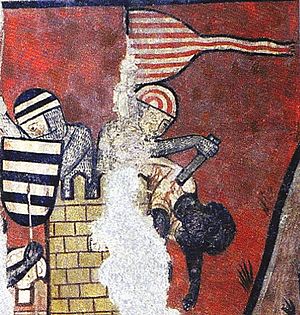

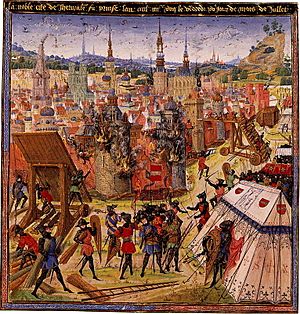

Assault on Madina Mayurqa |

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

||||||

| Units involved | |||||||

| Aragonese army 500 knights 15 000 peones Almogavars 25 ships 12 Galleys Aragonese Navy 18 Taridas (a ship of burden) 100 vessels |

1 000 knights 18 000 Infantry |

||||||

The conquest of the island of Majorca was a big event led by King James I of Aragon between 1229 and 1231. This conquest was part of a larger historical period called the Reconquista, where Christian kingdoms in Spain tried to take back lands from Muslim rule.

King James I and other important leaders agreed to invade Majorca in Tarragona on August 28, 1229. They made it open for anyone to join, promising fair shares of land.

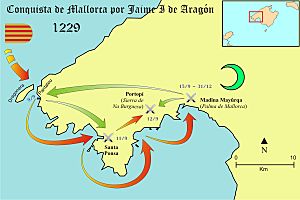

James I planned to land his troops in Port de Pollença, but strong winds pushed his fleet south. He landed on September 10, 1229, at midnight, in what is now Santa Ponsa. Even though the main city, Madina Mayurqa (now Palma de Mallorca), was captured in the first year, some Muslim groups kept fighting in the mountains for three more years.

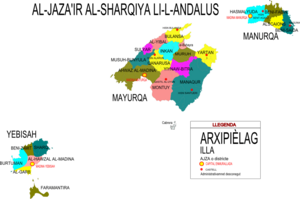

After winning, King James I shared the land among the nobles who helped him, following a special book called the Llibre del Repartiment (Book of Distribution). Later, he also conquered Ibiza in 1235. Menorca had already surrendered to him in 1231. James I created the Kingdom of Majorca, which became a separate kingdom for a while, before being taken back by the Crown of Aragon.

The first people to settle in Majorca after the conquest were mostly Catalans. Later, in the mid-13th century, more settlers arrived from Italy, Occitania, Aragon, and Navarre. Some Mudejar (Muslims who stayed in Christian lands) and Jewish people also remained. Jewish residents were given special rights and could manage their own taxes.

Contents

Why Majorca Was Important

Majorca was a very important island because of its location. It was a busy trading spot for merchants from places like Perpignan, North Africa, Genoa, Granada, Valencia, and Catalonia. Jewish, Catholic, and Muslim traders all met there to buy and sell goods.

The island was right between Christian and Muslim areas, making it a key point for sea travel. It was close to Spain, France, Italy, and North Africa. Majorca's economy depended a lot on international trade. It also had a busy market that was overseen by the Consulate of the Sea.

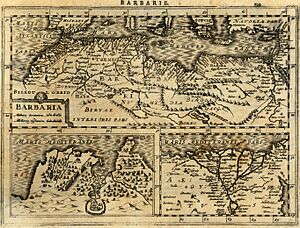

In 707, the island was attacked and looted by a Muslim leader. In 903, it was fully conquered by Issam al-Khawlani. Palma, which was still partly Roman, became part of the Emirate of Córdoba. The city was rebuilt and named Madina Mayurqa. From then on, Majorca grew a lot and became a base for pirates who attacked Christian ships in the western Mediterranean. This made trade difficult for cities like Pisa, Genoa, Barcelona, and Marseille. The island's economy relied on stolen goods from raids, sea trade, and taxes from farmers.

Earlier Attempts to Conquer the Island

In 1114, Ramon Berenguer III, Count of Barcelona, gathered nobles from Pisa and other cities. They launched an attack on Majorca to stop the pirate raids. Their goal was to take Majorca from Muslim control and set up a Christian government.

After an eight-month siege, Berenguer had to go back home because Barcelona was being threatened. The siege failed, but it helped set the stage for future Catalan naval power and stronger alliances among Christian kingdoms.

There's an old document from Pisa called Liber maiolichinus that talks about this expedition. It calls Ramon Berenguer III "Dux Catalensis" or "Catalanensis," which is thought to be the oldest written mention of Catalonia within the Count of Barcelona's lands.

After this failed siege, Majorca went back to Muslim control under the Banû Gâniya family.

Majorca Under Muslim Rule

After the Count of Barcelona left, Majorca was firmly under Muslim control. The island became an independent state within the Balearic Islands. Trade continued, even with ongoing attacks on ships. In 1148, Muhammad ben Gâniya signed a peace treaty with Genoa and Pisa.

During this time, Majorcans developed advanced farming methods using irrigation, building water sources, ditches, and channels. The land was divided into farms run by family groups. The main city, Medina Mayurqa, was the center for management and culture. It became a busy trade hub between the East and West.

Even though strict Islamic rules were followed in North Africa, Majorca was more influenced by Andalusian culture, which was less strict. In 1203, the Almohad fleet took Majorca, making it part of their empire. Abu Yahya became its governor in 1208, creating a semi-independent state.

The Crown of Aragon's Growing Power

After a period of peace and economic recovery, the Crown of Aragon started to expand its power. In 1212, the Muslims were defeated at the battle of Las Navas de Tolosa, which weakened the Almohad Empire. This allowed Aragon to become stronger. King James I was only five years old at this time. He was raised in a religious and military environment at the Templar castle of Monzón.

Planning the Conquest

King James I wanted to conquer Valencia and the Balearic Islands for several reasons. Valencia was rich and could provide new land for his people. The Balearic Islands would help Catalan and Provence merchants by stopping competition from Majorcan traders and getting rid of pirates who used Majorca as a safe place. Taking the islands was a way to get back at the pirates and start a plan to control trade with Syria and Alexandria. After his success in Majorca, James I decided to conquer Valencia.

Meetings and Decisions

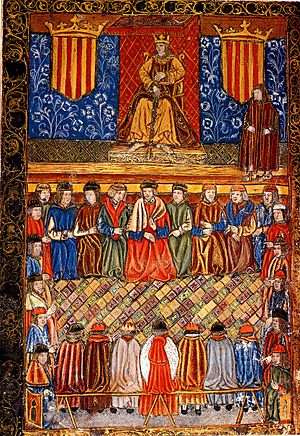

In December 1228, the Catalan Courts, a group of advisors, met in Barcelona. They talked about whether to attack the Balearic Islands or Valencia. The king promised the Bishop of Barcelona control over the churches on the islands.

Wealthy families in Barcelona, who had a lot of power and money, also supported the idea of new conquests. They wanted to make their investments more profitable. Father Grony, representing Barcelona, offered the city's help for the expedition. After several meetings, the king chose Majorca.

Merchants and business owners already supported the attack on Majorca. The support of the nobles was still needed. King James I said that an expert navigator named Pedro Martell encouraged him to go for Majorca during a dinner in Tarragona in late 1228.

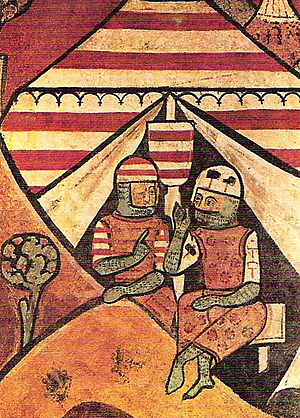

The goals of the expedition were clear: both political and religious. James I started his speech with a Latin verse asking for divine inspiration. He called the expedition a "good work." Religious groups like the Dominicans and the Knights Templar were very important to James I. The Templars had wanted to conquer the Balearics for a long time and believed the invasion was "God's will." They likely provided some of the best troops for the conquest.

Funding and Support

At the dinner, Catalan nobles promised their support and offered money and soldiers. They would get a share of the conquered lands based on how much help they gave. The king promised to appoint people to divide the land and loot fairly. Important leaders included the Master of the Knights Templar, the Bishop of Barcelona, Count Nuño Sánchez, and other wealthy gentlemen.

The king also asked for a loan of 60,000 Aragonese pounds from merchants, promising to pay it back after Majorca was taken. He told his citizens that he couldn't give them anything upfront, but victory would bring them property from Barcelona's beaches all the way to Majorca's.

Who Participated

The conquest was first planned for people from the Crown of Aragon. But when it was declared a crusade (a holy war), it was open to anyone who wanted to join, including private groups and Jewish people. Jewish communities, called Xuetes, were important for their industrial, commercial, and scientific skills. James I preferred them over some nobles because they wouldn't become political rivals. He encouraged them to move to the new lands to help the economy and settle the island.

James I had a Jewish doctor, Açac Abenvenist, from a young age, who even helped arrange a truce with the Muslims once.

Many nobles and bishops contributed soldiers and supplies. Nuño Sánchez brought 100 knights, Count Hugh IV of Ampurias brought 60, and Guillem II de Montcada, a very important noble, brought 400 knights. Church leaders also provided men. The Archbishop of Tarragona provided a galley (a type of ship) and four knights.

Not just nobles and church leaders, but also ordinary citizens and cities helped. Barcelona, Tortosa, and Tarragona, which had suffered most from pirate attacks, played a big role. The conquest was presented as a crusade against non-believers. King James I took the cross (a symbol of a crusader) in Lleida in April 1229.

Many cities from Provence (like Montpellier, Marseilles, and Narbonne) and Italy (like Genoa) also helped. Ramón de Plegamans, a rich businessman, was in charge of preparing the fleet.

Some Aragonese nobles also joined, even though they were more interested in conquering Valencia. About 200 knights from Aragon took part. Many of them settled on Majorca after the conquest to get a share of the spoils, which helped repopulate the island.

Final Preparations

Preparations for the invasion sped up. Pope Gregory IX sent two documents in February 1229. He allowed pardons for those who joined military groups against the Muslims in Aragon. He also reminded coastal towns like Genoa, Pisa, and Marseille not to trade military supplies with Majorca.

In August 1229, the archbishop of Tarragona donated food. The king again promised land grants and took oaths from knights.

The king was happy to see a powerful navy ready in Barcelona. There were about 100 small boats, 25 warships, 12 galleys, and 18 táridas (transport ships for horses and siege equipment).

Before leaving, the king, nobles, and army attended a Mass in Tarragona Cathedral. Many citizens came to watch the fleet depart from the rocky cliffs. The ships were arranged carefully, with warships surrounding the transport ships for protection.

The Armies

Christian Army

The Christian army was made up of about 1,500 knights and 15,000 foot soldiers. They came from various groups:

- Army of the House of Aragon: 150-200 knights.

- Army of Nuño Sánchez I of Roussillon and Cerdagne: 100 knights.

- Army of Guillem II de Bearn i Montcada: 100 knights.

- Army of Ramón Alemany de Cervelló í de Querol: 30 knights.

- Army of Hug V de Mataplana: 50 knights.

- Army of Berenguer de Palou II: 99 knights.

- Army of Guillem Aycard and Balduino Gemberto: 600 knights and several ships.

- Army of Hug IV of Empúries: 50 knights.

- Army of the bishop of Girona, Guillem de Montgrí: 100 knights.

- Army of the Abbot of Sant Feliu de Guíxols, Bernat Descoll.

- Army of the provost of the archbishop of Tarragona, Espárago de la Barca: 100 knights and 1,000 lancers.

- Army of the Knights Templar.

- Army of the Knights of Malta.

- Army of Guillem I de Cervelló: 100 knights.

- Army of Ferrer de San Martín: 100 knights.

- Army of Ramón II de Montcada: 25-50 knights.

- Army of Ramon Berenguer de Áger: 50 knights.

- Army of Galçeran de Pinós: 50 knights.

- Army of Bernat de Santa Eugènia: 30 knights.

- Army of Guillem de Claramunt: 30 knights.

- Army of Raimundo Alamán: 30 knights.

- Army of Pedro Cornel: 150 soldiers.

- Army of Gilabert de Cruilles: 30 knights.

Muslim Army

The Muslim king of Majorca, Abu Yahya, had between 18,000 and 42,000 men, and between 2,000 and 5,000 horses. Their weapons were similar to the Christians': meshes, spears, mallets, arrows, and leather shields. They also used Fustibalus (like slingshots) and light catapults called algarradas.

The Conquest Begins

Journey and Landing

The expedition left for Majorca from Salou, Cambrils, and Tarragona on September 5, 1229. The fleet had over 150 vessels, mostly Catalan. The Christian forces numbered between 800 and 1,500 armed men and 15,000 soldiers. The Muslim king, Abu Yahya, had a large army but received no help from outside Majorca.

Most Christian ships were private contributions. Peter Martell, who knew the Balearics well, was made head of the fleet. Guillem de Montcada served as lieutenant. King James I led the royal vessel.

A severe storm almost made the convoy turn back. After three days, the fleet reached Pantaleu island, near San Telmo. The storm was so bad that James I promised to build a cathedral to Santa Maria if they survived. Local stories say the first royal mass was held on this island.

While the Christians prepared, Abu Yahya had to deal with a revolt by his uncle. He pardoned 50 rebels so they could help defend, but many left. Some even sided with the Christians, like Ali de Pantaleu, who provided supplies to James I.

Battle of Portopí

The battle of Portopí was the main fight on open ground between James I's Christian troops and Abu Yahya's Muslim troops. It happened on September 12 in the Na Bourgeois mountains, between Santa Ponsa and the City of Majorca. The Christians won, but they lost many soldiers, including Guillem II de Bearne and his nephew Ramón, often called "the Montcada brothers."

The Muslim army was spread out in the mountains, knowing the Christians would have to cross them. Guillem de Montcada and Nuño Sánchez argued over who would lead the first attack. Montcada went first but fell into an ambush and was killed. James I followed with the rest of the army, unaware of their deaths. The Montcadas' bodies were buried in rich caskets at the Santes Creus monastery.

According to historian Desclot Bernat, the Christian soldiers sometimes hesitated. The king had to encourage them, even shouting, "For shame knights, shame!" But the Christians' military strength eventually made the Muslims retreat to the city. Desclot said only fourteen men died, mostly nobles, plus a few commoners.

That night, James I's army rested in Bendinat. A popular story says the king said "bé hem dinat" ("We have eaten well") there, giving the place its name. James I learned about the Montcadas' deaths two days later and sent their bodies for burial.

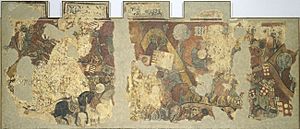

Siege of Medina Mayurqa

After the battle, the king and his troops moved their camp north of the city, between the wall and an area now called "La Real." James I ordered two trebuchets (large catapults) and a Turkish mangonel to be set up to bomb the city. The camp was chosen because it was near the city's water supply but far from Muslim defenses. James I also ordered a fence built around the camp for safety.

While the Christians camped, a wealthy Muslim named Ben Abed visited the king. He offered help and hostages from 800 Muslim villages in the mountains, asking for peace. This alliance was a big help to the Christians. Ben Abed gave James I horses, oats, goats, and chickens. The king gave him a banner so his messengers could move safely.

The Muslims inside the city fought back with their own machines. They even tied Christian prisoners on top of the walls to stop the bombing. But the prisoners shouted for their friends to keep firing, saying their death would bring glory. James I praised them and ordered more attacks. Seeing their plan fail, the Muslims brought the prisoners back inside. In return, James I catapulted the heads of 400 Muslim soldiers captured earlier.

Knowing they were losing, the Muslims offered to surrender. James I wanted to make a deal to save lives and the city, but the Montcadas' relatives and the bishop of Barcelona demanded revenge. Abu Yahya then stopped negotiations. The king had to agree with his allies, and the fight continued until Palma de Mallorca was taken.

Taking of Medina Mayurqa

To capture the walled city, the Christians usually surrounded it and waited for defenders to run out of water and food. But because of the weather and his troops' low morale, the king decided to break down the walls and attack the towers quickly. They used wooden siege towers, battering rams, and trebuchets.

After months of hard fighting, the Christians broke through the walls. The Muslims tried to build new walls quickly. One main Christian strategy was to use mines to weaken the walls, but the Muslims dug countermines.

Finally, on December 31, 1229, James I took Medina Mayurqa. Six soldiers managed to put a banner on a city tower, signaling the army to follow and shouting, "In, in, everything is ours!" Arnaldo Sorell, who led them, was later knighted for his bravery. The rest of the Christian army entered, shouting, "Santa Maria, Santa Maria!"

It is said that after taking the city, the Christians captured Abu Yahya. They burned parts of the city and killed many people who couldn't escape. The killing was so widespread that Christian troops suffered from a plague due to many unburied bodies.

According to James I's chronicles, 20,000 Muslims were killed, and 30,000 escaped. Another 20,000 people, including civilians and armed men, hid in the Tramuntana Mountains and Artà region but were later captured.

Sharing the Spoils

As soon as they entered the city, the conquerors started taking what they wanted, leading to arguments among the troops. The king suggested dealing with the Muslims who had fled to the mountains first, but the soldiers wanted to seize goods. The Bishop of Barcelona and Nuño Sánchez suggested a public auction. At first, everyone took what they wanted. When they were told they had to pay, they revolted. James I ordered them to bring everything to the Templar castle, promising fair distribution and threatening to hang looters. The city was looted until April 30, 1230.

Another problem was that troops started leaving the city once the main fighting was over. So, James I sent Pedro Cornel to Barcelona to get 150 knights to finish conquering the rest of the island.

Muslim Resistance

Because of the arguments among the conquerors, the Muslims who escaped were able to organize in the northern mountains of Majorca. They resisted for two years, until mid-1232. However, most of the Muslim population did not fight much and were disunited, which made the invasion easier.

To fight the resistance in the mountains, several military expeditions were launched. The first, led by James I, failed because the troops were weak and sick. The second raid in March found rebels in the Tramuntana Mountains who surrendered. A group of Christians found a cave where many Muslims were hiding, and they also surrendered.

James I, wanting to return home, left Berenguer de Santa Eugenia in charge as governor. Berenguer was responsible for stopping the Muslim resistance in the castles and mountains.

James I returned to Barcelona on October 28, 1230, to a big celebration. But then rumors spread that a large Muslim fleet was forming in Tunisia to retake the island. So, he returned to Majorca and captured the remaining Muslim castles: Pollensa, Santueri in Felanich, and Alaró. The last Muslim stronghold was in Pollensa, in the King's castle. Once these fortresses were taken, and he was sure no army would come from Africa, he went back to Catalonia.

Between December 31, 1229, and October 30, 1230, the towns in the center, south, east, and northeast of the island were taken. Those who couldn't flee to North Africa or Menorca were either enslaved or managed to stay on their land.

The last resistance made James I return to the island again in May 1232. About 2,000 Muslims hiding in the mountains refused to surrender to anyone but James I himself.

Muslim Viewpoint

A leading Majorcan historian, Guillermo Rosselló Bordoy, and philologist Nicolau Roser Nebot translated the first known Muslim account of the conquest of Majorca, called Kitab ta'rih Mayurqa. This work was discovered in a library in Tindouf. It's important because it tells the story from the perspective of the conquered.

The author was Ibn Amira Al-Mahzumi, born in Alzira in 1184. He fled to Africa during the war. His account is valuable because it's the only one from the Muslim side. It describes new details, like the landing site's Arabic name, Sanat Busa ("place of reeds").

The Muslim account confirms some details, like 50 ships in the Christian fleet and the detour along the Tramuntana coast. However, it differs on the treatment of the Muslim governor of Majorca. The Muslim account says he and his family were killed, which goes against the Christian accounts of a treaty. But it agrees on other details, like the capture of Christian ships in Ibiza as an excuse for the invasion, the landing site, the Battle of Portopí, and 24,000 Muslim deaths.

Dividing the Land

At the time of the invasion, Majorca had 816 farms. The land and property were divided as agreed in Parliament, following the Llibre del Repartiment. King James I split the island into eight sections. Half went to the king ("medietas regis"), and the other half went to the nobles who helped ("medietas magnatis").

The "medietas regis" included about 2113 houses, 320 workshops, and 47,000 hectares of land. The king divided this part among the military orders (like the Knights Templar), his officers, and free men and cities. The Knights Templar received 22,000 hectares, 393 houses, 54 shops, and 525 horses. The king's men got 65,000 hectares, cities received 50,000 hectares, and his son Alfonso got 14,500 hectares.

The "medietas magnatum" was divided among four main participants: Guillem Montcada, Hug of Empúries, Nuño Sánchez, and the Bishop of Barcelona. They then distributed the land among their own men, free people, and religious groups.

Where the Conquerors Came From

The conquerors came from many different places. Some current town names come from their new masters, like Deya, named after a knight of Nuño Sánchez. Estellenchs was named after gentlemen from Estella and Santa Eugenia.

According to the Llibre dels Repartiment, the conquered lands were divided among people from Catalonia (39.71%), Occitania (24.26%), Italy (16.19%), Aragon (7.35%), Navarra (5.88%), France (4.42%), Castille (1.47%), and Flanders (0.73%).

Most of the native Muslim population was killed or expelled, so there weren't enough people to farm the land. In 1230, special rules were made to attract more settlers for farming. The new Majorcan population mainly came from Catalonia, especially the northeast and east. A small Muslim population remained. As a result, the language of Majorca became an eastern Catalan dialect, called Majorquin.

Many common Majorcan surnames today come from the original lands of the first settlers, like Català (Catalan), Pisa (Pisa), Cerdà (from Cerdagne), and Balaguer.

Before the conquest, there were few or no Christians on the island. A mosque, now the Sant Miquel church, was converted for the first Christian mass after the city was taken. This suggests that Christian worship was not common before then.

Menorca and Ibiza

After conquering Majorca, James I decided not to attack Menorca directly because of the losses and the need for troops to conquer Valencia. Instead, they used a clever plan. Ramón de Serra, a Templar commander, suggested sending a group to Menorca to ask for surrender. The king sent the Master Templar, Bernardo de Santa Eugénia, and Knight Templar, Pedro Masa, with their ships. While they talked with the Muslims, James I ordered large fires to be built at Castle of Capdepera that could be seen from Menorca. This made the Menorcans believe a huge army was ready to invade. This worked, leading to Menorca's surrender and the signing of the Treaty of Capdepera. Menorca remained under Muslim rule but paid taxes to the king of Majorca. The island was finally taken by Alfonso III of Aragon in 1287.

James I assigned the conquest of Ibiza to the archbishop of Tarragona, Guillem de Montgrí, his brother Bernardo de Santa Eugénia, Count of Roussillon, Nuño Sánchez, and the Count of Urgel, Pedro I. The islands were taken on August 8, 1235, and became part of the Kingdom of Majorca. People from Ampurdán settled there.

What Happened Next

The new Christian city was divided into two parishes: Santa Eulalia and San Miguel. These became centers for administration and religion. The San Miguel church is considered the oldest temple in Palma because it was built on a Muslim mosque.

Majorca became a territory of the Crown of Aragon, called "regnum Maioricarum et insulae adyacentes" (Kingdom of Majorca and adjacent islands). They started using Catalan laws. The city of Madina Mayurqa was renamed "Ciutat de Mallorca" (City of Majorca).

The city then had a period of economic growth because its location was perfect for trade with North Africa, Italy, and the rest of the Mediterranean.

On September 29, 1231, James I traded the kingdom of Majorca for lands in Urgel with his uncle, Prince Peter I of Portugal. This deal was finalized on May 9, 1232, making the prince lord of the island.

The justice system changed, with new laws and the creation of public notaries.

Islam was suppressed after the conquest. While not all Muslims were enslaved, they weren't encouraged to convert, nor were they allowed to practice their religion publicly. Those who helped the invasion kept their freedom and could work as craftsmen or traders. Many others were sold into slavery.

The Knights Templar were allowed to settle 30 Muslim families to help with olive harvesting. They also made a deal with Jewish people to guarantee water supply, and the Jewish community helped with navigational charts.

The main source of income for the king came from feudal payments and taxes from non-Christian communities.

The main mosque was used as a Christian church until around 1300, when construction began on the Santa Maria cathedral. This cathedral is known for being built very close to the sea and having one of the world's largest rose windows.

The city's water supply system, which used ditches, became private property through royal grants.

After the Black Death caused a population drop, farming and textile production grew. The city remained an important trade hub.

Although winemaking was introduced by the Romans, the Muslim population limited wine consumption. After the conquest, grape cultivation was brought back, leading to a period of prosperity.

Settling the land was slow. For 15 years after the conquest, only a quarter of the available land was farmed. Most people settled in the capital city. By 1270, the native Muslim population was gone, either expelled or replaced by new settlers or slaves.

After James I died, his son James II inherited the kingdom of Majorca, which became independent from the Crown of Aragon for a time. Later, it returned to the Crown. Some streets in Palma, like Abu Yahya square and "calle 31 de diciembre" (December 31 Street), remember this history. December 31 is the date the Christian troops entered the city.

Legacy and Celebrations

Events

In 2009, "the landing routes" tour opened in Santa Ponsa. It has 19 panels in four languages and lets people walk three different routes: the Christian route, the Muslim route, and the battle route.

On September 9, 2010, during the 781st anniversary of the landing, the mayor of Calvia, Carlos Delgado Truyols, said that the conquest was not just Catalan but involved all of Christendom. He also supported the Majorcan dialect of Catalan as the official language.

In 2010, the remains of a Berber woman from that time were found in Arta. She had hidden in a cave with keys to her home and other people, likely unaware the island had been invaded three months earlier.

The capture of the capital is celebrated every year on December 30 and 31 during the "Festa de l'Estendart" (Festival of the Standard). This festival is one of Europe's oldest civil festivals. During the event, a proclamation is made, and flowers are offered to the statue of James I in Palma's Plaza of Spain. The festival's name refers to the soldier who placed the royal standard on the tower, signaling the Christian troops to attack.

Literature and Art

In Catalan folk stories, there are many tales about James I. One tells of him at a banquet, ordering his food and drink to be left untouched until his victorious return from the island.

James I's troops also included Almogavars, who were mercenaries known for their fighting skills.

Christian soldiers wore hemispherical helmets with nose protectors, made of iron plates and often painted for durability and identification.

After the conquest, civil Gothic architecture grew rapidly in Majorca. Wealthy citizens built palaces and held auctions.

Many Islamic buildings were destroyed during the conquest. Only the baths in the Palma mansion of Can Fontirroig survive. They are thought to be from the tenth century and might have been part of a Muslim palace. They still have well-preserved arches and 12 columns.

Many artworks show the conquest. Between 1285 and 1290, the Royal Palace of Barcelona had paintings of the conquest, showing cavalry, laborers, spearmen, and archers. Fragments of other paintings in the Palacio Aguilar show the Barcelona courts meeting in 1228.

In 1897, the Mallorcan Circle held a painting competition about the conquest. One winning painting, Rendición del walí de Mallorca al rey Jaime I (Surrender of the wali of Majorca to King James I) by Richard Anckermann, shows James I triumphantly entering the city.

See also

In Spanish: Conquista de Mallorca por Jaime I para niños

In Spanish: Conquista de Mallorca por Jaime I para niños

| Precious Adams |

| Lauren Anderson |

| Janet Collins |