Eighty Years' War, 1621–1648 facts for kids

The final part of the Eighty Years' War happened between 1621 and 1648. This long war was fought between the Spanish Empire and the new Dutch Republic. It started when a break in fighting, called the Twelve Years' Truce (1609–1621), ended. The war finally finished with the Peace of Münster in 1648.

Even though the Dutch and Spanish were on opposite sides in a smaller conflict, the War of the Jülich Succession, they were careful not to fight each other directly. This helped the truce last. However, talks to make a lasting peace failed, and the war started again in 1621 as everyone expected. This conflict became a part of the bigger Thirty Years' War that had already begun in 1618 in Central Europe.

During this final phase, there were many back-and-forth battles. Spain captured Breda in 1625, but the Dutch took it back in 1637. The Dutch Republic also managed to conquer important forts and cities. These included Oldenzaal (1626), Groenlo (1627), and the big city of 's-Hertogenbosch (1629). They also took Venlo, Roermond, and Maastricht (1632) along the Meuse River. Later, they captured Sas van Gent (1644) and Hulst (1645) in Zeelandic Flanders.

Plans for peace talks in 1629–1630 didn't work out. Bigger plans to capture Brussels with help from Spanish nobles also failed. The Spanish army, called the Army of Flanders, also stopped several Dutch attempts to surprise and besiege Antwerp.

A deal between France and the Dutch in 1635 didn't change much on the ground. This was partly because of terrible things that happened during the Sack of Tienen. These events made people in the Southern Netherlands lose sympathy for the French and Dutch.

However, France's involvement and unhappiness in Spain about the war's costs changed Spain's focus. Spain started to focus on stopping the Catalan Revolt, which France supported. This led to a standstill and money problems for both sides. Spain's army was tired, and the Dutch wanted to be officially recognized as an independent country. These reasons finally convinced both sides in the mid-1640s to talk about peace.

The result was the Peace of Münster in 1648. This peace confirmed most of the agreements that had been made during the Truce of 1609.

Contents

Why the War Started Again

During the Twelve Years' Truce, people tried to make a lasting peace. But two main problems could not be solved. First, Spain wanted Catholics in the Dutch Republic to have religious freedom. The Dutch, in turn, wanted the same freedom for Protestants in the Southern Netherlands. Second, there were growing disagreements about trade routes to colonies in the Far East and the Americas. The Dutch navy was expanding its trade routes, often taking over Portuguese areas that belonged to Spain at the time.

In March 1621, a diplomat named Petrus Peckius the Younger tried one last time to extend the truce. He suggested that the Dutch Republic could run its own affairs if it simply recognized the King of Spain as its ruler in name. The Dutch were very angry and rejected this idea. They had fought hard for their independence. So, the war began again. There was also a risk that this war would fully join with the bigger Thirty Years' War that had started in 1618.

Dutch Involvement in the Thirty Years' War

Even before the truce ended, a civil war began in Bohemia in 1618. The Bohemian rebels were fighting their king, Ferdinand. They looked for help, and only the Dutch Republic was ready to give it. The Dutch supported Frederick V, Elector Palatine, who became the King of Bohemia. Prince Maurice of Orange, a Dutch leader, encouraged Frederick and gave him money and promises of military help. The Dutch played a big part in starting the Thirty Years' War.

Maurice wanted to put the Dutch Republic in a better position if the war with Spain started again. He also needed to keep control at home after some internal conflicts. The Spanish government saw this internal weakness and decided to be bolder in Bohemia. So, the Bohemian war quickly became a fight between Spain and the Dutch Republic. Even after the Protestant army lost badly at the Battle of White Mountain in 1620, the Dutch kept supporting Frederick.

In the end, the Dutch help was not enough. Frederick and his wife, Elizabeth, had to flee to The Hague. They became known as the Winter King and Queen because their rule was so short. Maurice tried to get them to defend their lands, but it was too late. Spain and the Imperial forces won in Germany.

Talks about renewing the truce continued in 1620 and 1621. Archduke Albert of Austria, the ruler of the Southern Netherlands, wanted to renew it. But when his diplomat, Petrus Peckius, mentioned the Dutch recognizing the King of Spain's rule, the Dutch immediately refused. This idea united the northern provinces against peace. Secret talks continued, but Spain demanded that the Dutch leave the East and West Indies, open the Scheldt River for Antwerp's trade, and allow public Catholic worship in the Republic. These demands were unacceptable to the Dutch, and the truce ended in April 1621.

The war didn't start right away. Maurice kept sending secret offers to Isabella, Albert's wife, even after Albert died in July 1621. But these secret talks became known, and people who wanted to restart the war, especially investors in the Dutch West India Company, opposed them. So, nothing came of these peace efforts.

The Republic Under Attack (1621–1628)

The truce officially ended on April 9, 1621. Spain's King Philip III had just died, and his 16-year-old son, Philip IV, took over. Soon after, Archduke Albert of Austria also died, and the Southern Netherlands returned to Spanish rule. Isabella Clara Eugenia became governor for Philip IV.

The Spanish government believed the truce had hurt their economy. They thought the Dutch had gained too many trade advantages. The blockade of Antwerp had also caused that city to decline. Spain felt threatened by Dutch trade in the East Indies and their raids on Spanish South America. They wanted to stop these. Spain also felt the Dutch had used the truce to build a strong navy and army, which seemed aimed at stopping Spain's goals.

Spain decided to use both military force and economic warfare. They immediately ordered all Dutch ships out of Spanish ports and restarted strict trade bans. After rebuilding their army, the Spanish commander Spinola launched attacks. He captured Jülich in 1622 and Steenbergen in Brabant. Then he besieged the important city of Bergen-op-Zoom. This siege was a disaster for Spain, as many soldiers died from disease. Spinola had to give up the siege. This made Spain decide that besieging strong Dutch forts was a waste of money. They would focus on economic warfare instead. Even though Spinola later successfully captured Breda in 1625, Spain still decided to play defense in the Netherlands. Maurice, the Dutch leader, died in April 1625.

Economic Warfare in the 1620s

Spain increased its economic attacks, which felt like a siege of the entire Dutch Republic. The naval war became more intense. Spanish ships attacked Dutch shipping in the Mediterranean, forcing the Dutch to sail in convoys with naval escorts. This made Dutch shipping more expensive and less competitive. Spain also increased its navy in Dutch waters, especially with privateers called Dunkirkers, who attacked Dutch fishing boats.

The Dutch herring trade, a key part of their economy, was badly hurt. Spain blocked salt supplies needed to preserve herring and closed inland waterways for Dutch trade. This caused Dutch butter and cheese prices to fall, and wine and herring prices to rise in other areas. The salt embargo was part of a larger trade ban. At first, the Dutch tried to get around it by using neutral ships, but Spain created a special system to enforce the embargo. This system made the embargo very effective, hurting Dutch trade with the Baltic Sea and shifting trade to English ships.

Spain also closed inland waterways for Dutch river traffic after 1625. This cut off Dutch trade with Germany. While these measures hurt the Dutch economy and reduced their ability to fund the war, they were not enough to defeat the Republic. The United East India Company (VOC) and the Dutch West India Company (WIC) provided many jobs and brought in huge profits. Supplying armies also helped farmers in the Dutch inland provinces.

Dutch Republic Gets Stronger (1625–1628)

After Maurice died in April 1625, his half-brother Frederick Henry, Prince of Orange took over as Prince of Orange and army commander. It took some time for him to be appointed governor (stadtholder) of Holland and Zeeland. During this time, more moderate leaders returned to power in Holland. This helped bring back political stability to the Republic.

The Dutch government's money situation improved. Spain's military pressure eased after Breda fell in 1625. This allowed the Dutch to steadily increase their army. The new governor of Friesland and Groningen, Ernst Casimir, recaptured Oldenzaal, forcing Spanish troops out of Overijssel. England also joined the war as an ally in 1625, which helped the Dutch. Frederick Henry cleared the Spanish from eastern Gelderland in 1627 after recapturing Grol.

The Dutch also won a big naval victory in the Battle in the Bay of Matanzas in 1628. Piet Pieterszoon Hein captured a Spanish treasure fleet, which gave the Dutch much-needed money and hurt Spain's finances. Spain also got involved in the War of the Mantuan Succession, which drained their troops and money in the Netherlands. This gave the Dutch Republic a military advantage.

The Republic Attacks (1629–1635)

Siege of 's-Hertogenbosch (1629)

In 1629, the Dutch army had 77,000 soldiers, much more than the Spanish Army of Flanders. This allowed Frederick Henry to lead 28,000 soldiers to besiege 's-Hertogenbosch. This was a very important fortress city. While the siege was happening, Imperial and Spanish forces attacked from Germany, reaching Amersfoort. But the Dutch quickly gathered militias and garrison troops, forming a huge army of 128,000. This allowed Frederick Henry to continue the siege.

When Dutch troops surprised the Spanish fortress of Wesel, which was a main Spanish supply base, the invaders had to retreat. 's-Hertogenbosch surrendered in September 1629. This city had been thought to be impossible to capture. Its loss was a major blow to Spain. Historians say it was a "shattering blow to Spanish prestige" and showed that the Dutch now had a strategic advantage. King Philip IV of Spain offered an unconditional truce, but it was rejected.

Political Problems (1630–1631)

The capture of Wesel and 's-Hertogenbosch caused a sensation in Europe. It showed the Dutch were strategically stronger. 's-Hertogenbosch was a key part of Spain's forts in Brabant, and its loss left a big hole. Philip IV, shaken by this, offered a truce. The Dutch refused to consider it until the Imperial forces left Dutch land. Once they did, the offer was discussed, but it divided the Dutch provinces.

Some provinces, like Friesland and Zeeland, rejected the peace offer. Frederick Henry seemed to favor it, but Holland was divided. People who wanted to continue the war wanted to "liberate" more of the Spanish Netherlands. Those who had invested in the WIC feared a truce would stop their plans to invade Portuguese Brazil. The peace and war parties in Holland were balanced, leading to a standstill. Nothing was decided in 1629 and 1630.

To break this deadlock, Frederick Henry planned a big attack in 1631. He wanted to invade Flanders and push towards Dunkirk. He took 30,000 men and 80 cannons on 3,000 river boats. But a large Spanish force appeared behind him. This caused an argument with civilian leaders who were trying to manage the campaign. The civilians won, and Frederick Henry had to order a retreat. On September 12 and 13, 1631, the Dutch won the naval Battle of the Slaak, stopping the Spanish from dividing the Republic.

Meuse Campaign and Failed Talks (1632–1634)

In 1632, Frederick Henry was finally allowed to launch a major attack along the Meuse River. He wanted to prepare for conquering the main cities of the Southern Netherlands. He promised that Catholics would be allowed to practice their religion freely in any areas the Dutch army conquered. He invited people in the Southern Netherlands to "throw off the yoke of the Spaniards." This message was very effective.

Frederick Henry invaded the Meuse valley with 30,000 troops. He quickly took Venlo, Roermond, and Sittard. As promised, Catholic churches and clergy were not bothered. Then, on June 8, he began the siege of Maastricht. Spanish and Imperial forces tried to help the city but failed. On August 20, 1632, Frederick Henry used mines to break the city walls. Maastricht surrendered three days later. Here too, the Catholic religion was allowed to continue.

The infanta Isabella, the Spanish ruler, had to call a meeting of the Southern provinces' States General. This was the first time since 1598. They met in September and most southern provinces wanted immediate peace talks with the Dutch. They wanted to protect their land and the Catholic religion. However, King Philip and his minister Olivares secretly canceled the authorization for these talks. They thought the southern provinces were taking over royal power.

On the Dutch side, there was still disagreement. Frederick Henry wanted a quick result, but some provinces opposed talks. Holland was divided. Eventually, four provinces allowed talks only with the southern provinces, leaving Spain out. This made any agreement useless, as Spain controlled the troops. The peace party in the Republic finally started meaningful talks in December 1632, but valuable time had been lost, allowing Spain to send more soldiers. Both sides had demands that were hard to agree on.

By June 1633, the talks were about to fail. Frederick Henry suggested giving the other side an ultimatum to accept Dutch demands. But he lost the support of the "peace party" in Holland, led by Amsterdam. These leaders wanted to offer more concessions for peace. The peace party gained power in Holland, standing up to the governor for the first time since 1618. However, Frederick Henry got the support of most other provinces. They voted to break off the talks in December 1633. Despite gaining forts along the Meuse, Dutch attempts to attack Antwerp and Brussels in the next years failed. The Dutch were disappointed that the people in the Southern Netherlands did not support them more.

Franco-Dutch Alliance (1635–1640)

While peace talks were slow, other events happened in Europe. Sweden had joined the Thirty Years' War in Germany in 1630, supported by France and the Dutch. The Swedes used new Dutch army tactics and won many battles. However, after Spain's war with Italy ended in 1631, Spain rebuilt its army. The Cardinal-Infante brought a strong army and defeated the Swedes at the Battle of Nördlingen (1634). He then marched to Brussels, where he took over after Isabella died. Spain's power in the Southern Netherlands grew stronger.

The Dutch, with no hope of peace with Spain, decided to take France's offer for an alliance more seriously. This change in strategy caused a political shift in the Republic. The peace party in Amsterdam opposed the treaty with France because it would stop the Republic from making a separate peace with Spain. This would tie the Dutch to French policies and limit their independence. Frederick Henry then sided more with the radical Calvinists who supported the alliance. This shift led to more power being held by a small group of the governor's favorites. Unfortunately, this also made it easier for foreign diplomats to influence policy with bribes.

The alliance treaty, signed in Paris on February 8, 1635, meant the Dutch and French would invade the Spanish Netherlands together. The treaty planned to divide the Spanish Netherlands between them. If the people rebelled against Spain, the Southern Netherlands would become independent like Switzerland. But France would get the Flemish coast, Namur, and Thionville. The Dutch would get Breda, Geldern, and Hulst. If the people resisted, the country would be divided directly. French-speaking areas and western Flanders would go to France, and the rest to the Dutch. This meant Antwerp might rejoin the Republic, and the Scheldt River would reopen for trade. Amsterdam was very much against this. The treaty also said that the Catholic religion would be fully kept in the areas given to the Dutch. This angered radical Calvinists in the Republic.

Dividing the Spanish Netherlands was harder than expected. Spain's strategy for this two-front war was very effective. Spain defended well against the French invasion in May 1635. The French and Dutch had some early success, winning a battle and capturing Tienen. But a huge fire broke out in Tienen, destroying much of the city and supplies. This was either on purpose or by accident. The terrible things done during the Sack of Tienen made the people of the Southern Netherlands lose any sympathy they had for the French and Dutch. The new generation, who were strong Catholics, distrusted the Calvinist Dutch even more than they disliked the Spanish. The French and Dutch leaders were embarrassed and blamed each other. Spain used the Sack of Tienen to spread propaganda against the rebels and Protestants.

The Siege of Leuven (June 24 – July 4, 1635) was a disaster for the allies. The Cardinal-Infante attacked the Dutch with his full force. The Spanish Army of Flanders now had 70,000 men, matching the Dutch forces. After the French and Dutch invasion was stopped, Spanish troops attacked recently conquered Dutch areas. In July 1635, Spanish troops captured the very important fortress of Schenkenschans. This fort was on an island in the Rhine River and controlled a key entry point into the Dutch heartland. Cleves was also captured, and Spanish forces overran the Meierij region.

The Dutch could not let Schenkenschans remain in Spanish hands. Frederick Henry gathered a huge force to besiege the fortress, even during the winter of 1635–36. Spain held on tightly, hoping to pressure the Dutch into giving up. But the planned Spanish invasion never happened. Frederick Henry forced the Spanish garrison in Schenkenschans to surrender in April 1636. This was a severe blow for Spain.

The next year, Frederick Henry managed to recapture Breda (July 21 – October 11, 1637). This was his last big success for a long time. The peace party in the Republic, against his wishes, cut war spending and reduced the size of the Dutch army. This happened even though the Dutch economy had improved greatly in the 1630s. The Spanish river blockade had ended in 1629. The end of the Polish–Swedish War also helped Dutch trade. The start of the Franco-Spanish War in 1635 closed other trade routes for Flemish goods, forcing the South to pay high Dutch wartime taxes. Increased German demand for food and military supplies also helped the Dutch economy. Successes of the VOC in the Indies and the WIC in the Americas (where the WIC had taken over parts of Portuguese Brazil) also brought in much money.

Despite this economic boom, Dutch leaders were not eager to keep military spending high. The failure of the Battle of Kallo in June 1638 did not help Frederick Henry's campaigns. His campaigns in the next few years were not successful. His colleague, Hendrik Casimir, died in battle during the failed siege of Hulst in 1640.

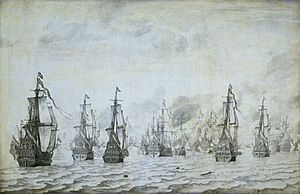

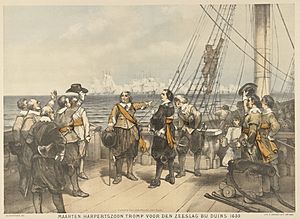

However, the Dutch Republic won big victories elsewhere. The war with France closed the "Spanish Road," making it hard for Spain to send more soldiers from Italy. So, Spain decided to send 20,000 troops by sea in a large fleet. But the Dutch navy, led by Maarten Tromp and Witte Corneliszoon de With, destroyed this fleet in the Battle of the Downs on October 31, 1639. This showed that the Dutch Republic now had the strongest navy in the world. The English navy could only watch as the battle happened in English waters.

Colonial Battles

As more European countries built their empires, wars spread to their colonies. Battles for valuable colonies were fought in places like Macau, the East Indies, Ceylon, Formosa (Taiwan), the Philippines, and Brazil. The most important of these conflicts became known as the Dutch-Portuguese War. The Dutch built a trading empire around the world, using their strong navy to their advantage. The Dutch East India Company managed trade with the East, and the Dutch West India Company did the same for the West.

In the Western colonies, the Dutch government mostly supported privateering in the Caribbean. This helped drain Spain's money and fill Dutch coffers. The most successful raid was when Piet Pieterszoon Hein captured most of the Spanish treasure fleet in the 1628 Battle in the Bay of Matanzas. This allowed Frederick Henry to pay for the siege of 's-Hertogenbosch and caused big problems for Spain's army payments. The Dutch also tried to conquer existing colonies or start new ones in Brazil, North America, and Africa. Most of these were only partly successful or lasted a short time. In the East, Dutch activities led to the conquest of many profitable trading colonies, which greatly contributed to the Dutch Golden Age.

In Asia and the Americas, the war went well for the Dutch. These parts of the war were mostly fought by the Dutch West and East India companies. These companies had special powers, including the power to wage war and make treaties for the Dutch Republic. After the WIC invaded Portuguese Brazil in 1630, the Dutch colony, called New Holland, grew. It stretched from the Amazon River to the São Francisco River. Many sugar plantations thrived there, allowing the company to control the European sugar trade.

The colony was also a base for conquering Portuguese areas in Africa. Starting in 1637 with the capture of Elmina Castle, the WIC gained control of the Gulf of Guinea on the African coast. This gave them control of the slave trade to the Americas. In 1641, a WIC expedition conquered Portuguese Angola. The Spanish island of Curaçao (important for salt) was conquered in 1634, along with other Caribbean islands.

However, WIC control of Brazil began to fall apart when Portuguese colonists rebelled in 1645. By then, the official war with Portugal was over, as Portugal had rebelled against Spain in December 1640. The Dutch soon made a ten-year truce with Portugal, but this only applied to Europe. The overseas war continued. By the end of 1645, the WIC had lost control of northeast Brazil.

In the Far East, the VOC captured three of the six main Portuguese strongholds in Portuguese Ceylon between 1638 and 1641, working with the king of Kandy. In 1641, Portuguese Malacca was conquered. Most of the Portuguese territory would be conquered after the war ended.

The VOC's results against Spanish possessions in the Far East were less impressive. Battles in the Philippines in 1610, 1617, and 1624 resulted in Dutch defeats. An expedition in 1647 also ended in defeats. These expeditions were mainly meant to bother Spanish trade with China and capture the annual Manila galleon, not to conquer the Philippines.

The Final Years (1640–1648)

Peace Talks Gain Ground

Rebellions in Portugal and Catalonia in 1640 greatly weakened Spain. Spain then tried more and more to start peace talks. At first, Frederick Henry refused because he didn't want to hurt the alliance with France. A clerk, Cornelis Musch, even stopped letters from the Brussels government trying to reach the Dutch about peace. Frederick Henry also wanted to keep Holland divided to maintain his power.

But after 1640, opposition to the war united Holland. The reason was money: Holland's leaders were less willing to pay for the huge army Frederick Henry had built, especially since the threat from Spain was smaller. This large army was also achieving less. In 1641, only Gennep was captured. The next year, Amsterdam managed to reduce the army size from over 70,000 to 60,000, despite Frederick Henry's objections.

Start of Peace Negotiations

Holland's leaders continued to try to reduce the governor's influence. This helped take power away from his favorites who controlled secret committees. This was important for the general peace negotiations that started in 1641 in Münster and Osnabrück. The main countries involved in the Thirty Years' War (France, Sweden, Spain, the Emperor, and the Dutch Republic) were there. Holland made sure it was involved in writing the instructions for the Dutch delegation. The Dutch demands that were agreed upon included:

- Spain giving up the entire Meierij district.

- Recognition of Dutch conquests in the Indies (East and West).

- Permanent closing of the Scheldt River to Antwerp's trade.

- Trade concessions in the Flemish ports.

- Lifting of Spanish trade bans.

While peace talks moved very slowly, Frederick Henry had a few final military successes. In 1644, he captured Sas van Gent and Hulst in what became States Flanders. However, in 1646, Holland, tired of the slow pace of peace talks, refused to approve the yearly war budget unless progress was made. Frederick Henry then gave in and started to push for peace. Still, there was much opposition from others, like France's supporters and Frederick Henry's son William. So, peace could not be made before Frederick Henry's death on March 14, 1647.

Spain's Disadvantage

Spain was finally forced to recognize the independence of the Dutch provinces. These had been some of its most valuable possessions. Many reasons are given for Spain's defeat, but the main one is that Spain could no longer afford the war. Both Spain and the Dutch spent a lot of money, but the Dutch grew stronger as the war went on. Because of the Netherlands' booming economy, its soldiers were paid on time. In Spain, the situation was bad. Soldiers were often owed months or even years of pay. As a result, they fought with less enthusiasm and rebelled many times. Also, Spanish mercenaries spent their money in Flanders, not Spain. This meant three million ducats left Spain and entered the Dutch economy every year.

Peace of Münster

On January 30, 1648, the war ended with the Treaty of Münster between Spain and the Netherlands. This treaty was part of the larger Peace of Westphalia that also ended the Thirty Years' War in Europe. The treaty officially recognized the Dutch Republic as an independent state. It also legally recognized the long-standing separation of the Netherlands and the Old Swiss Confederacy from the Holy Roman Empire.

The Dutch Republic kept control over the lands it had conquered in the later stages of the war. This outcome was unexpected and unplanned. The Dutch Republic, now recognized, was not exactly the same as the provinces that had first formed the Union of Utrecht in 1579. Southern cities that signed the Union, like Antwerp and Ghent, had been reconquered by Spain in the 1580s. Despite losing some members, the remaining provinces of the Union managed to keep fighting. The 1579 Union of Utrecht had promised loyalty to Philip II, but the 1581 Act of Abjuration rejected him. Then, in 1588, the rebel States-General decided to become a republic.

Each province was now governed by its own States, which were executive boards with many members. These boards had existed before the war but now took on a governing role, which was new in Europe. The borderlands conquered by the Dutch army in the final stages of the war became the Generality Lands. These were governed directly by the States-General. In terms of religion, a unique balance was created. All people in the Republic had freedom of conscience, meaning they could believe what they wanted. But only members of the Calvinist Dutch Reformed Church could practice their religion openly. Other religions were tolerated in private, but non-Calvinists faced discrimination and could not hold public office.

What Happened Next

The French and Dutch had agreed to negotiate with Spain together. But while the Dutch and Spanish quickly agreed on their peace treaty by January 1648, the French and Spanish could not agree. The French tried to stop their Dutch allies from signing the deal, as the Dutch felt the French were stalling to get more from Spain. The Dutch decided to make a separate peace with Spain on January 30, 1648. This was confirmed on May 15, 1648. The Franco-Spanish War continued for eleven more years until the Treaty of the Pyrenees in 1659.

Portugal was not part of the 1648 Peace of Münster. The overseas Dutch–Portuguese War (1602–1663) continued fiercely after the ten-year truce of 1640 ended. In Brazil and Africa, the Portuguese managed to reconquer most of the land they had lost to the WIC after a long fight. This led to a short war in Europe from 1657–60, during which the VOC completed its conquests in Ceylon and India. Portugal had to pay the WIC for its losses in Brazil.

The early, chaotic years of the Eighty Years' War, with civil revolts and massacres, mostly ended for the northern provinces after they formed the Republic in 1588. They expelled Spanish forces and brought peace, safety, and wealth to their people. However, the countryside of Brabant, Flanders, and the areas that are now the Belgian and Dutch Limburg provinces continued to be devastated by decades of regular warfare. Armies forced farmers to give up their food or destroyed crops to starve the enemy. Both sides also taxed farmers in the areas around 's-Hertogenbosch after the Dutch captured it in 1629.

The upper and middle classes in the Dutch Republic, especially in Holland, Zeeland, and Utrecht, thrived during this time. This period is known as the Dutch Golden Age, with a generally high quality of life. However, wealth and health were not spread equally. Lower classes in Holland's cities were worse off than the new wealthy class of regenten. Most people in the eastern provinces were poor farmers ruled by traditional nobles. In the south, where the Generality Lands had no political say, the mostly Catholic population was tolerated but faced discrimination and were often poor farmers.

| Selma Burke |

| Pauline Powell Burns |

| Frederick J. Brown |

| Robert Blackburn |