Engineer Cantonment facts for kids

Quick facts for kids |

|

|

Engineer Cantonment

|

|

Excavations at Engineer Cantonment, 2015

|

|

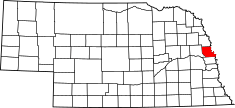

Washington County, Nebraska

|

|

| Nearest city | Fort Calhoun, Nebraska |

|---|---|

| NRHP reference No. | 15000795 |

| Added to NRHP | November 17, 2015 |

Engineer Cantonment was a special science camp in Washington County, Nebraska. It was set up near the Missouri River in what is now Omaha, Nebraska. From October 1819 to June 1820, a group of scientists stayed here. They studied the plants, animals, and rocks of the area. They also met with local Native American groups. Their eight-month study of nature was the first big "biodiversity inventory" (a list of all living things) ever done in the United States!

After the scientists left, the camp was forgotten for a long time. In 2003, it was found again by archaeologists. They studied the site from 2003 to 2005. In 2015, Engineer Cantonment was added to the National Register of Historic Places, which is a list of important historical sites.

Contents

History of the Expedition

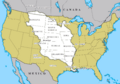

In 1803, the United States bought the Louisiana Territory from France. This huge area included the land around the Missouri River. The famous Lewis and Clark Expedition explored this new land from 1804 to 1806. They found many animals whose furs could be traded. President Thomas Jefferson wanted Americans to use these resources. He believed fur traders would help the U.S. expand into the new territory.

After the War of 1812 (1812–1815) with the British Empire, the U.S. was worried about British influence in the upper Missouri River area. To protect American land and fur trade, President James Monroe and Secretary of War John C. Calhoun planned the Yellowstone Expedition in 1818. Over 1,000 soldiers were ordered to travel up the Missouri River. Their goal was to build forts along the river.

The Long Expedition's Journey

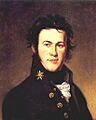

A scientific team joined the military expedition. This team was led by Major Stephen H. Long. He was an engineer in the U.S. Army. Long had explored other parts of the Mississippi River area before. He suggested exploring the Great Lakes and upper Mississippi by steamboat. He also wanted a group of scientists to come along.

Long gathered a team of excellent scientists. They included:

- William Baldwin, a doctor and botanist (plant expert)

- Augustus Edward Jessup, a geologist (rock and earth expert)

- Thomas Say, a zoologist (animal expert)

- Titian Peale, an assistant naturalist (nature expert)

- Samuel Seymour, an artist

This group was the largest and best-trained team of civilian scientists to join a government expedition at that time.

Calhoun allowed Long to design a special steamboat for the expedition. It was called the Western Engineer. It was built in Pittsburgh in 1818–1819. This boat was one of the first "stern-wheelers" (boats with a paddle wheel at the back). It was about 75 feet (23 meters) long. To impress the Native American people they met, the boat had a special design. It had a flag showing a white man and a Native American shaking hands. The front of the boat looked like a huge black serpent with its mouth open, "vomiting smoke."

Traveling Up the Missouri River

The Western Engineer left Pittsburgh in the spring of 1819. It traveled down the Ohio River and then up the Mississippi to St. Louis. In June 1819, Long's team started their journey up the Missouri River.

Going upstream was slow. The river's strong current made the boat move slowly, less than three miles (five kilometers) per hour. Also, mud from the river kept clogging the steamboat's engine. The team also made several stops, including one for a week in Franklin, Missouri.

Sadly, the expedition lost one of its members in Franklin. Baldwin, the botanist, had been sick with tuberculosis for a long time. He was too ill to continue and died a few weeks later.

The military expedition also had trouble. Many of their steamboats broke down or never reached the Missouri River. The soldiers had to finish their journey using keelboats. They pulled these boats from the riverbanks using long ropes.

Winter at Engineer Cantonment

On September 17, 1819, Long's team reached Fort Lisa. This was a fur-trading post north of present-day Omaha, Nebraska. On September 19, they set up their winter camp about half a mile (0.8 kilometers) from Fort Lisa. They named this temporary camp Engineer Cantonment, after their steamboat, the Western Engineer.

The military group arrived later. They reached the area of present-day Fort Calhoun, Nebraska in late September or early October. There, they built Cantonment Missouri. This was meant to be a permanent fort. However, floods destroyed it the next spring. The soldiers then moved to a new, safer spot on the bluffs, which became Fort Atkinson.

Major Long left Engineer Cantonment in October to return east. Geologist Jessup also resigned from the expedition. Major Thomas Biddle, who kept the expedition's official journal, also left. However, Say, Peale, and Seymour stayed at Engineer Cantonment for the winter. Long's assistant, James Duncan Graham, and engineer William Henry Swift also stayed. Six crew members from the Western Engineer and a nine-man military guard were also there.

The team at Engineer Cantonment spent the next six months exploring the area. They met with the Pawnees and the Otoes. They visited Pawnee and Omaha villages and were visited by other Native American groups. They also mapped the camp's location and studied the geology and the living things (biota) of the area.

Changes in 1820

Long returned to Engineer Cantonment on May 27, 1820. He brought two new team members. Dr. Edwin James became the expedition's surgeon, geologist, and botanist. Captain John R. Bell took over keeping the official journal.

Long also brought new orders from Washington. Due to money problems from the Panic of 1819 (a financial crisis), the expedition had to be smaller. Instead of going further up the Missouri, Long's team was now ordered to follow the Platte River west. Then they would travel south along the Rocky Mountains to the sources of the Arkansas and Red Rivers. Finally, they would follow those rivers downstream to the Mississippi.

The Long expedition left Engineer Cantonment on June 6, 1820. They never returned to the camp. There are no records of anyone else using the site after they left.

Biology and Discoveries

The scientists' eight-month stay at Engineer Cantonment was very important. It led to what is called "the first biodiversity inventory undertaken in the United States." Other expeditions, like Lewis and Clark's, only spent short times in different places. This meant they couldn't study nature in great detail. But the long stay at Engineer Cantonment allowed the scientists to study the local plants and animals very closely. They tried to make a complete list of everything living there.

The study of plants was limited. The expedition lost its botanist, Baldwin, before reaching the camp. His replacement, Dr. James, arrived only a short time before the expedition left. Still, they described 51 plants from 34 families. Four of these were thought to be new to science.

Thomas Say, who is known as "the father of American entomology" (the study of insects), described the new animals found at the site. These included:

- 46 insects from 30 families (38 of them new to science)

- 143 birds (4 of them new)

- 33 mammals (6 of them new)

- 14 reptiles and 2 amphibians (all previously known)

- 14 snails (1 of them new)

Changes in Local Wildlife Since 1820

The environment and the animals in the Engineer Cantonment area have changed a lot since 1820. Back then, the Missouri River curved a lot and flooded in the spring. The area had many oxbow lakes (U-shaped lakes) and wetlands. Frequent prairie fires kept large forests from growing. The river valley had scattered groups of trees, and the bluffs (cliffs) were not heavily wooded. The prairie west of the bluffs had no trees at all.

Since then, the river has been straightened and kept in one channel. Dams built upstream now control flooding. The wetlands have been drained and turned into farmland. Also, because fires are now controlled, riparian forests (forests along rivers) have grown. These are mostly cottonwood trees. The bluffs are now also heavily wooded.

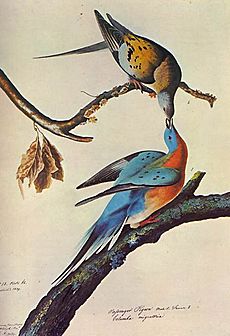

Several animal species recorded at Engineer Cantonment are no longer found in the area. Two birds, the passenger pigeon and the Carolina parakeet, are now completely extinct. The local type of gray wolf, Canis lupus nubilus, is also extinct. Other large meat-eating animals, like black bears, eastern spotted skunks, and river otters, are gone from the area. The mountain lion disappeared for many years but has been seen again in eastern Nebraska in the 21st century. Hunting and habitat loss have also caused three large plant-eating animals to disappear: American bison, pronghorn, and elk.

Two types of bats, the eastern pipistrelle and the evening bat, have moved into the area. They like forests and forest edges. In Nebraska, their range has grown from the very southeast corner to cover the entire eastern third of the state. This has also happened with other birds, mammals, and insects from eastern woodlands. Their ranges have expanded as riparian forests have grown along prairie rivers.

However, two forest-dwelling rodents found at Engineer Cantonment, the eastern chipmunk and the eastern gray squirrel, have disappeared since 1820. Even though there are more forests now, it's thought that the change in tree types might be the reason. These animals prefer older oak-hickory woods, not the cottonwood forests that have grown along the Missouri River.

Archaeological Discoveries

After 1820, there are no records of anyone using the Engineer Cantonment site again. As years passed, its exact location was forgotten. People in the 20th century tried to find it, but failed. Many believed the site had been destroyed by floods, river changes, or modern construction.

In 2002, the Nebraska State Historical Society (NSHS) began looking for old sites in the Omaha area. They thought Engineer Cantonment and Fort Lisa might be in the northern part of their search area. Also, plans to improve a local road meant they needed to check for important historical sites.

While at Engineer Cantonment, the artist Titian Peale had drawn sketches of the camp and its surroundings. In early 2003, NSHS archaeologists noticed that a part of the bluffs looked like Peale's drawing. It even included a wide ravine (a narrow valley) that Peale had shown behind the camp. They dug a trench at this possible site. They found limestone pieces, some burned, which might have been from a fireplace. When they sifted the dirt, they found a brass button and a piece of a trigger guard. These items were similar to things found at Fort Atkinson.

Using Ground-penetrating radar (a tool that sees underground) and more digging, they found a building. It was about 30 feet (9 meters) east-west and 48 feet (15 meters) north-south. The building had two rooms and a double fireplace in the middle. They also found pieces of ceramic tobacco pipes and tableware. These items were typical of what people used around 1820. The quality of the items also helped confirm the site was Engineer Cantonment. Common soldiers used tin cups, but the wine bottles and painted porcelain found here were used by people like the expedition's scientists.

Peale's drawing showed two buildings, one behind the other, near the mouth of a wide ravine. In the front, near the first building, the Western Engineer and several keelboats were docked in what looked like an old river bend (an oxbow cutoff). Even though this oxbow was gone by the 21st century, digging east of the two-room building found the edge of this old harbor.

The archaeologists tried to find the second building shown in Peale's drawing, but they were not successful. They first looked to the west and southwest of the known building, but found nothing. Then they thought the second building might be east of the known one. Digging in that direction found limestone pieces and a few artifacts. However, they couldn't find clear evidence of a building. These eastern items were buried less deeply than the remains of the known building. It's thought that the western building's remains were covered and protected by mud from the ravine. The eastern building, however, might have been buried shallowly or not at all, and its remains were washed away by weather and water.

Archaeological digging continued through the 2005 season. After that, the site was left open but covered by a large portable building to protect it. This allowed for future digs. In 2011, the Missouri River flooded, damaging the site. In the spring of 2015, archaeologists and students from the University of Nebraska–Lincoln's Archeological Field School removed the mud left by the flood. This uncovered the excavations from 2003–2005 again.

In 2015, Engineer Cantonment was officially listed in the National Register of Historic Places.

Images for kids

-

The Louisiana Purchase added a huge amount of land to the U.S.

-

The passenger pigeon was once common but is now extinct.

-

The eastern chipmunk used to live in the area but is no longer found there.

| Frances Mary Albrier |

| Whitney Young |

| Muhammad Ali |