Passenger pigeon facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Passenger pigeon |

|

|---|---|

|

|

| 1898 photograph of a live passenger pigeon | |

| Conservation status | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | |

| Class: | |

| Order: | |

| Family: | |

| Genus: |

Ectopistes

Swainson, 1827

|

| Binomial name | |

| Ectopistes migratorius (Linnaeus, 1766)

|

|

The passenger pigeon (Ectopistes migratorius) was a type of pigeon. It was once the most common bird in North America. Sadly, this amazing bird is now extinct.

Contents

About the Passenger Pigeon

The passenger pigeon was a bird called Ectopistes migratorius. It used to live in huge groups that moved from place to place. These groups, called flocks, sometimes had more than two billion birds! They could stretch for one mile (1.6 km) wide and 300 miles (500 km) long across the sky. It could take several hours for a single flock to fly by.

Some people think there were three to five billion passenger pigeons in the United States when Europeans first arrived. Others believe their numbers grew later. This might have happened because fewer Native Americans were around due to European diseases. This meant less competition for food.

This bird went from being one of the most common birds in the world in the 1800s to being completely gone by the early 1900s. At one time, passenger pigeons had one of the largest groups of any animal. Only the Rocky Mountain locust had bigger groups.

Their numbers started to drop when Europeans settled more land. This meant the pigeons lost some of their homes. But the main reason they disappeared was because people started hunting them for meat. Pigeon meat became a cheap food for many people in the 1800s. This led to a lot of hunting. Their numbers slowly went down between 1800 and 1870. Then, they dropped very quickly between 1870 and 1890. The very last passenger pigeon, named Martha, died on September 1, 1914, in Cincinnati, Ohio.

In the 1700s, people in Europe called this bird "tourtre." But in North America, it was called "tourte." Today, in French, it's known as "pigeon migrateur." In some Native American languages, like Algonquian, it was called amimi or omiimii. The English name "passenger pigeon" comes from the French word passager, which means "to pass by."

What Did They Look Like?

The Passenger Pigeon was bigger than a Mourning Dove. It was about the same size as a large Rock Pigeon. These pigeons usually weighed about 340–400 grams (12–14 oz). Males were about 42 cm (16.5 in) long, and females were about 38 cm (15 in) long.

The Passenger Pigeon had a bluish-gray head and back. Its chest was a wine-red color. Male birds had black stripes on their wings. They also had patches of pinkish colors on the sides of their necks. These colors could change to shiny metallic bronze, green, and purple in different light. Female and young birds looked similar but had duller gray backs and lighter rose chests. Their necks were also less colorful.

Their wings were long and wide. Their tail was very long, about 20–23 cm (8–9 in). It was gray to blackish with a white edge.

How They Lived

The Passenger Pigeon was a very social bird. It lived in huge groups that spread over hundreds of square miles. They nested together, with up to a hundred nests in one tree! Some people think it might have been the most common bird on Earth at its peak. One expert believed they made up between 25 and 40 percent of all land birds in the US.

Scientists think these birds survived because of their huge numbers. There was safety in being part of a flock that had hundreds of thousands of birds. When such a large flock settled in an area, the number of local animal predators was very small compared to all the birds. This meant the predators (like wolves, foxes, weasels, and hawks) could not harm the whole flock much. Passenger pigeon flocks often perched on each other's backs. This is unusual even for birds that like to be social.

It is believed that these birds played a big role in the forests of North America before settlers arrived. They would break tree branches and leave droppings. This helped change where certain types of trees grew.

What They Ate

The main foods for the passenger pigeon were beechnuts, acorns, chestnuts, seeds, and berries. They found these foods in the forests. In spring and summer, they also ate worms and insects. These pigeons could even spit out food from their crop if they found something better to eat.

Reproduction and Life Cycle

These birds built their nests together in forest areas. These spots needed to have enough food and water nearby. A single nesting area could cover many thousands of acres. The birds were so close together that hundreds of nests could be in just one tree. We don't have exact numbers, but one large nesting area in Wisconsin was said to cover 850 square miles (2,200 km2). About 136,000,000 birds were thought to be nesting there. They bred from March to September, mostly in April and May.

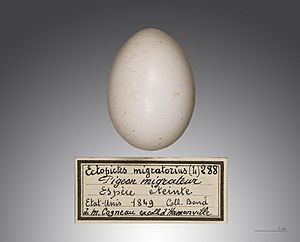

Their nests were made loosely from small sticks and twigs. They were about a foot wide. The female laid only one white, long egg per nesting. The egg hatched in about twelve to fourteen days. Both parents helped sit on the egg and feed the baby bird. When born, the young bird was naked and blind. But it grew very quickly. When it got feathers, it looked like a female adult, but its feathers had white tips. It stayed in the nest for about fourteen days. The parents fed and cared for it. By this time, it was big and plump, often weighing more than its parents. It was ready to take care of itself and soon flew to the ground to find its own food.

Where They Lived

The time of their spring migration depended on the weather. Small groups sometimes arrived in northern nesting areas as early as February. But the main migration happened in March and April. The flocks traveled huge distances. They might not return to the same place for many years. They could fly for hours at 60 miles per hour. This meant they could cover very large areas.

In summer, Passenger Pigeons lived in forests across North America. This was east of the Rocky Mountains, from eastern and central Canada to the Northeastern United States. In the winters, they flew south to the Southern United States. Sometimes, they even went to Mexico and Cuba.

Why They Disappeared

The Passenger Pigeon became extinct for two main reasons. The biggest reason was that people hunted them for meat on a huge scale. Losing their forest homes also played a part.

The large flocks and group nesting of the birds became very dangerous when humans started hunting them. When Passenger Pigeons were gathered together, especially at a huge nesting site, it was easy for people to kill many of them. So many were killed that there were not enough birds left to have babies and keep the species going. As the flocks got smaller, their social way of life broke down. This meant they were doomed to disappear.

A naturalist named Paul R. Ehrlich said that the Passenger Pigeon's extinction shows an important rule for saving animals. He said you don't have to kill the very last pair of a species for it to go extinct. Sadly, he noted, people haven't learned this lesson.

Hunting Them

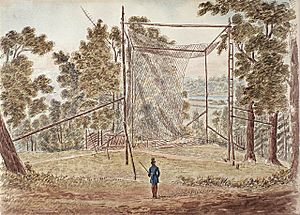

Before Europeans arrived, Native Americans sometimes hunted pigeons for food. In the early 1800s, commercial hunters began catching and shooting the birds. They sold them in cities as food. They also used them as live targets for trap shooting. Sometimes, they even used them as fertilizer for farms.

Once pigeon meat became popular, hunting for money started in a very big way.

Pigeons were sent by the boxcar-load to cities in the east. In New York City in 1805, a pair of pigeons sold for two cents. By the 1850s, people noticed that the number of birds seemed to be going down. But the hunting continued, and even got faster. This was because more railroads and telegraphs were built after the American Civil War.

At Petoskey, Michigan in 1878, 50,000 birds were killed every day for almost five months. The adult birds that survived tried to nest again in new places. But professional hunters killed them before they could raise any young. A historical marker remembers these events, including the last big nesting in 1878. One hunter was said to have killed "a million birds" himself. He earned a lot of money from this.

Hunters would also soak grain in alcohol to make the birds drunk. This made them easier to kill. They also set smoky fires under nesting trees to make the birds fly out of their nests.

Losing Their Home

Another big reason for their extinction was deforestation. This means cutting down too many trees. The birds traveled and had babies in huge numbers. This meant there were so many of them that predators could not make a big dent in their population. As their numbers went down and they lost their homes, the birds could no longer rely on being in huge groups for safety. Without this protection, many experts believe the species could not survive.

Trying to Save Them

In 1857, a law was proposed in Ohio to protect the Passenger Pigeon. But a committee in the Senate said, "The passenger pigeon needs no protection. It has so many babies. It has the huge forests of the North as its breeding grounds. It travels hundreds of miles for food. It is here today and somewhere else tomorrow. No normal amount of killing can make them fewer, or be missed from the countless numbers that are born each year."

People who wanted to save animals could not stop the hunting.

By the early 1900s, the last group of passenger pigeons were all related. Professor Charles O. Whitman at the University of Chicago kept them. The last try to breed the remaining birds was done by Whitman and the Cincinnati Zoo. They even tried to have rock doves raise passenger pigeon eggs. Whitman sent Martha, who would be the last known bird, to the Cincinnati Zoo in 1902.

The Last Wild Birds

The last time a wild passenger pigeon was definitely seen was near Sargents, Pike County, Ohio, on March 22, 1900. A boy killed the bird with a BB gun. Many other sightings were reported in the early 1900s, but they were not confirmed. From 1909 to 1912, rewards were offered for a living bird, but none were found. However, unconfirmed sightings continued until about 1930.

Reports of Passenger Pigeon sightings kept coming from Arkansas and Louisiana. They were seen in groups of ten or twenty until the early 1900s.

A naturalist named Charles Dury, from Cincinnati, Ohio, wrote in September 1910: "One foggy day in October 1884, at 5 a.m. I looked out of my bedroom window. Six wild pigeons flew down and sat on the dead branches of a tall poplar tree about one hundred feet away. I watched them happily, feeling like old friends had come back. They quickly flew away and disappeared in the fog. That was the last time I ever saw any of these birds in this area."

Martha

On September 1, 1914, Martha, the last known Passenger Pigeon, died at the Cincinnati Zoo in Cincinnati, Ohio. Her body was frozen in a block of ice. Then it was sent to the Smithsonian Institution. There, it was prepared, studied, photographed, and put on display. Today, Martha (named after Martha Washington) is kept in the museum's collection. She is not currently on display. A statue of Martha stands at the Cincinnati Zoo.

John Herald, a bluegrass singer, wrote a song about Martha. It is called "Martha: Last of the passenger pigeons." The song tells the story of the Passenger Pigeon's extinction and Martha's life in her cage at the Cincinnati Zoo.

Images for kids

-

Earliest published illustration of the species (a male), Mark Catesby, 1731

-

Mounted male passenger pigeon, Field Museum of Natural History

-

Band-tailed pigeon, a species in the related genus Patagioenas

-

The physically similar mourning dove is not closely related.

-

Musical notes documenting male vocalizations, compiled by Wallace Craig, 1911

-

Acorns in South Carolina, among the diet of this bird

-

Internal organs of Martha, the last individual: cr. denotes the crop, gz. the gizzard, 1915

-

Male and female by Louis Agassiz Fuertes, frontispiece of William Butts Mershon's 1907 The Passenger Pigeon

-

Life drawing by Charles R. Knight, 1903

-

"The Folly of 1857 and the Lesson of 1912", frontispiece to William T. Hornaday's Our vanishing wild life (1913), showing Martha in life, the endling of the species.

-

Martha at the Smithsonian Museum, 2015

-

Taxidermized male and female, Laval University Library

See also

In Spanish: Paloma migratoria para niños

In Spanish: Paloma migratoria para niños

| Aurelia Browder |

| Nannie Helen Burroughs |

| Michelle Alexander |