Ernie Pyle facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Ernie Pyle

|

|

|---|---|

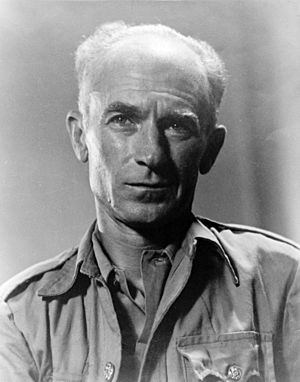

Ernie Pyle in 1945

|

|

| Born |

Ernest Taylor Pyle

August 3, 1900 |

| Died | April 18, 1945 (aged 44) Iejima, Okinawa Prefecture, Empire of Japan

|

| Cause of death | Killed in action |

| Resting place | National Memorial Cemetery of the Pacific, Honolulu |

| Occupation | Journalist |

| Spouse(s) |

Geraldine Siebolds

(m. 1925) |

Ernest "Ernie" Taylor Pyle (born August 3, 1900 – died April 18, 1945) was a famous American journalist. He won a Pulitzer Prize for his writing. Ernie Pyle is best known as a war correspondent during World War II. He wrote amazing stories about the everyday lives of American soldiers.

Before the war, from 1935 to 1941, Pyle wrote popular newspaper articles about ordinary people across North America. When the United States joined World War II, he used his simple, friendly writing style to report from the war zones. He covered the war in Europe (1942–44) and the Pacific (1945). In 1944, he won the Pulitzer Prize for his unique stories about soldiers. He wrote from their point of view, showing what life was like for them. Ernie Pyle was killed by enemy fire on Iejima during the Battle of Okinawa.

When he died in 1945, Ernie Pyle was one of the most well-known war reporters in America. His articles were printed in 400 daily and 300 weekly newspapers. President Harry Truman said that Pyle was the best at telling the story of American soldiers. He believed Pyle deserved thanks from everyone in the country.

Contents

- Ernie Pyle's Early Life and Education

- Ernie Pyle's Personal Life

- Ernie Pyle's Career

- Ernie Pyle's Death

- Ernie Pyle's Writing Style

- Ernie Pyle's Popularity

- Ernie Pyle's Legacy

- Honors and Awards for Ernie Pyle

- Tributes to Ernie Pyle

- Ernie Pyle Historic Sites

- Ernie Pyle's Published Works

- Images for kids

- See also

Ernie Pyle's Early Life and Education

Ernie Pyle was born on August 3, 1900, on a farm near Dana, Indiana. His parents were Maria and William Pyle. His father was a farmer, but Ernie didn't like farming. He wanted a more exciting life.

After high school, he joined the U.S. Naval Reserve during World War I. He started training, but the war ended before he could finish.

In 1919, Pyle went to Indiana University. He wanted to become a journalist. The university didn't have a journalism degree back then, so he studied economics. He took as many journalism classes as he could. He started working for the student newspaper, the Indiana Daily Student. He became the city editor and news editor. Ernie Pyle's simple, storytelling writing style, which he learned at IU, later made him famous.

In 1922, Pyle and some friends took a break from school. They worked on a ship and traveled to Japan. The ship stopped in places like Shanghai, Hong Kong, and Manila. This trip made Pyle even more interested in traveling the world.

Pyle left college in January 1923, just one semester before graduating. He got a job as a reporter for the Daily Herald in La Porte, Indiana. After three months, he moved to Washington, D.C., to work for The Washington Daily News.

Ernie Pyle's Personal Life

In 1923, Ernie Pyle met Geraldine Elizabeth "Jerry" Siebolds in Washington, D.C. They got married in July 1925. In the early years of their marriage, they traveled all over the country together. In his newspaper articles about their trips, Pyle often called her "That Girl who rides with me."

In 1940, Pyle bought land near Albuquerque, New Mexico, and built a small home. This house became their main home in the United States. Ernie and Jerry Pyle had a difficult relationship. They divorced in April 1942, but they remarried in March 1943 while Pyle was reporting from North Africa. They did not have any children.

Jerry Pyle's health got worse after Ernie died on April 18, 1945. She passed away in November 1945.

Ernie Pyle's Career

Early Reporting and Aviation Stories

In 1923, Ernie Pyle joined The Washington Daily News as a reporter. He later became a copy editor. This was the start of his career with Scripps-Howard newspapers, which lasted his whole life.

In 1926, Pyle and his wife quit their jobs and traveled over 9,000 miles across the United States in a Ford Model T. After working briefly in New York City, Pyle returned to the Daily News in 1927. He started writing one of the country's first and most famous aviation columns. He wrote about flying for four years, even though he never became a pilot himself. He flew about 100,000 miles as a passenger.

Human-Interest Columnist

In 1932, Pyle became the managing editor at the Daily News. After three years, he took on a new writing job. In 1934, he took a vacation in the western United States. When he returned, he wrote a series of articles about his trip and the people he met. These stories were very popular.

In 1935, Pyle left his editor job to write his own national column. He became a "roving reporter" for Scripps-Howard newspapers. For the next six years, Pyle and his wife traveled across the United States, Canada, Mexico, and parts of Central and South America. He wrote about interesting places and people. His column, called "the Hoosier Vagabond," appeared six days a week. These articles made him well-known before he became famous as a war correspondent.

World War II Correspondent

Ernie Pyle first went to London in 1940 to report on the Battle of Britain. He saw the German bombing of the city. He returned to Europe in 1942 as a war correspondent. Pyle spent time with the U.S. military during the North African Campaign, the Italian campaign, and the Normandy landings. He went back to the United States in September 1944 to rest. He then traveled to the Asiatic-Pacific Theater in January 1945. Pyle was covering the invasion of Okinawa when he was killed in April 1945.

Reporting from Europe

Pyle's wartime articles usually described the war from the point of view of the common soldier. He spent time with different parts of the U.S. military and reported from the front lines. His stories from the European theater are collected in his books Here is Your War (1943) and Brave Men (1944).

In his reports from the North African Campaign in 1942 and 1943, Pyle shared his early war experiences. He became friends with both soldiers and officers. Pyle especially liked the infantry soldiers, calling them "the underdogs."

Pyle lived among the U.S. servicemen and could interview anyone he wanted. As a non-fighter, he could also leave the front when he needed to. He took breaks in September 1943 and September 1944 to go home and rest from the stress of combat.

Pyle wrote a famous article from Italy in 1944. He suggested that soldiers fighting in combat should get "fight pay," just like airmen got "flight pay." In May 1944, the U.S. Congress passed a law, known as the Ernie Pyle bill. It gave soldiers 50 percent extra pay for combat service. Pyle's most famous article, "The Death of Captain Waskow," was written in Italy in December 1943. It was published in January 1944 and was a highlight of his career.

After the campaigns in North Africa and Italy, Pyle went to England in April 1944. He covered the preparations for the Allied landing at Normandy. Pyle was one of the twenty-eight war reporters who went with U.S. troops during the first invasion in June 1944. He landed at Omaha Beach.

In July 1944, Pyle was almost hit by an accidental bombing by the U.S. Army Air Forces near Saint-Lô in Normandy. A month later, after seeing the liberation of Paris, Pyle told his readers in a column that he was exhausted. He said his "spirit is wobbly and my mind is confused" and that he would "go off my nut" if he heard one more shot or saw one more dead person. He felt he had "lost track of the point of the war." He hoped a rest at home in New Mexico would help him feel better.

Reporting from the Pacific

Pyle went to the Pacific in January 1945 for his last assignment. He covered the U.S. Navy and Marine forces. Pyle argued against the Navy's rule that reporters couldn't use sailors' names in their stories. He won a small victory when the rule was lifted just for him. Pyle traveled on the aircraft carrier USS Cabot. He felt the Navy life was easier than the infantry in Europe. He wrote some articles that were not very positive about the Navy. Other reporters and soldiers criticized him for this. Pyle admitted his heart was with the soldiers in Europe, but he kept working. He reported on the naval action during the Battle of Okinawa, which was the largest water landing in the Pacific during World War II.

Ernie Pyle's Death

Ernie Pyle sometimes felt he might not survive the war. He even wrote letters to friends predicting this.

On April 17, 1945, Pyle landed with the U.S. Army's 305th Infantry Regiment on Ie Shima (now Iejima). This was a small island near Okinawa that Allied forces had captured but still had some enemy soldiers. The next day, Pyle was riding in a jeep with Lieutenant Colonel Joseph B. Coolidge and three other officers. Their vehicle came under fire from a Japanese machine gun. The men quickly took cover in a ditch. Coolidge reported, "A little later Pyle and I raised up to look around. Another burst hit the road over our heads ... I looked at Ernie and saw he had been hit." A machine-gun bullet hit Pyle in the head, killing him instantly.

Pyle was buried on Ie Shima among other soldiers who died in battle. The men of the 77th Infantry Division built a monument at the spot where he died. It says: "At this spot the 77th Infantry Division lost a buddy, Ernie Pyle, 18 April 1945." General Eisenhower said that the soldiers in Europe had "lost one of our best and most understanding friends."

Former First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt often quoted Pyle's war reports. She wrote in her column that she admired "this frail and modest man who could endure hardships because he loved his job and our men." President Harry S. Truman also honored Pyle. He said, "No man in this war has so well told the story of the American fighting man as American fighting men wanted it told."

After the war, Pyle's remains were moved to a U.S. military cemetery on Okinawa. In 1949, he was one of the first people buried at the National Memorial Cemetery of the Pacific in Honolulu, Hawaii.

Ernie Pyle's Writing Style

Ernie Pyle's unique storytelling style developed during his time at Indiana University and as a human-interest reporter. As a war correspondent, he usually wrote from the point of view of the common soldier. He explained how the war affected the men, instead of just reporting on troop movements or generals. His simple, informal stories about events made his writing special and made him famous during the war.

Other journalists praised Pyle's writing. Walter Morrow, an editor, said Pyle's articles from his travels in the 1930s were "the most widely read thing in the paper." During World War II, Pyle continued to write from what he called "the worm's-eye view." His articles were not only in U.S. newspapers but also regularly published in the U.S. armed forces newspaper, Stars and Stripes.

Pyle's "everyman" approach to his war reporting earned him the Pulitzer Prize for journalism in 1944.

Ernie Pyle's Popularity

Ernie Pyle was very well known and liked by the American military. Sergeant Mack Morris wrote that Pyle's secret was his ability to report on the war "on a personal plane." Artist George Biddle said that Pyle was popular because "he writes about and writes to the great, anonymous American average." Soldiers felt he gave them recognition.

Pyle's newspaper articles were popular with readers of all ages in the United States. In November 1942, his articles were in 42 newspapers. By April 1943, that number grew to 122 newspapers. When he came home for breaks during the war, reporters and photographers wanted to interview him. In 1943, Pyle also gave radio interviews to help sell war bonds. When he died, his articles were in 400 daily and 300 weekly newspapers.

Ernie Pyle's Legacy

Ernie Pyle is called "the most important war correspondent of his time." He became famous worldwide for his World War II reports from 1942 to 1945. Today, war correspondents, World War II veterans, and historians still see Pyle's reports as the standard for war reporting. Life magazine once said that Pyle's "smooth, friendly prose succeeded in bridging a gap between soldier and civilian."

Pyle is best remembered for his World War II newspaper reports about the real experiences of ordinary Americans, especially the soldiers in Europe. His legacy also includes the stories of soldiers who would otherwise be unknown. "The Death of Captain Waskow" is considered Pyle's most famous article.

Besides his writing, Pyle's legacy includes the Ernie Pyle bill. He suggested this idea in one of his articles in early 1944. Congress passed the law in May 1944 to give American soldiers a 50 percent pay increase for their combat service. The U.S. Army also used Pyle's idea of adding overseas service bars to uniforms. These bars showed that a soldier had served six months overseas.

Ernie Pyle's writings and other materials about his life are kept at the Lilly Library at Indiana University Bloomington, the Ernie Pyle World War II Museum in Dana, Indiana, and other places.

Honors and Awards for Ernie Pyle

- He won the National Headliners Club Award twice (1943 and 1944).

- He received the Pulitzer Prize for his war reporting in 1944.

- He was featured on the cover of Time magazine on July 17, 1944.

- He won the Raymond Clapper Memorial Award in 1944 from the journalism fraternity Sigma Delta Chi.

- The Sons of Indiana in New York City named Pyle the Hoosier of the Year in 1944.

- He received honorary doctorates from the University of New Mexico and Indiana University.

- The U.S. government gave Pyle the Medal for Merit after he died in July 1945.

- In 1983, he was given the Purple Heart after his death. This is a rare honor for a civilian.

- He received the American Legion's Distinguished Service Medal after his death in 1945.

Tributes to Ernie Pyle

- Workers at Boeing-Wichita paid for and built a Boeing B-29 Superfortress bomber named the "Ernie Pyle." It was dedicated on May 1, 1945. This plane flew in the Pacific during the war and survived.

- During the American occupation of Japan (1945–1955), the Tokyo Takarazuka Theater was renamed the Ernie Pyle Theater. It was a popular spot for American soldiers.

- Scripps-Howard Newspapers created the Ernie Pyle Memorial Fund in 1953. This fund supports the Ernie Pyle Award, given yearly to reporters who write in a style similar to Pyle's.

- In 1954, Indiana University named the building that housed its School of Journalism Ernie Pyle Hall.

- In 1970, a memorial plaque was placed at Pyle's burial site in the National Memorial Cemetery of the Pacific in Honolulu, Hawaii.

- On May 7, 1971, the U.S. Postal Service issued a 16-cent postage stamp in Pyle's honor.

- Indiana University started the Ernie Pyle Scholars Honors Program in 2006 for new journalism students.

- In 2014, a bronze statue of Pyle was put in front of Franklin Hall on the IU Bloomington campus.

- The first Ernie Pyle Legacy Foundation Scholarship was given in 2017 to a journalism student at the University of New Mexico.

- August 3, 2018, was the first National Ernie Pyle Day. This was thanks to a resolution from U.S. senators from Indiana.

Ernie Pyle Historic Sites

- In 1947, Ernie Pyle's last home in Albuquerque, New Mexico, became a memorial. Since 1948, this home, known as the Ernie Pyle Library, has been the first branch of the local library system. It has some of Pyle's belongings and archives. It was named a National Historic Landmark in 2006.

- The Ernie Pyle World War II Museum is Pyle's restored birthplace in Dana, Indiana. It includes a farmhouse and a visitor center made from two World War II-era Quonset huts. The museum shows displays about Pyle's wartime career.

Other Places Named for Ernie Pyle

- Elementary schools named for Pyle are in Clinton, Indiana; Indianapolis, Indiana; Bellflower, California; and Fresno, California.

- Ernie Pyle Middle School is in Albuquerque, New Mexico.

- A part of U.S. Highway 36 in Indiana is called the Ernie Pyle Memorial Highway. There is also a memorial rest park named for him along this highway.

- A road at Fort Riley, Kansas, and a street at Fort Meade, Maryland, are named after him.

- A small island in Cagles Mill Lake, Indiana, is named for him.

- The Ernie Pyle Reserve Center is at Fort Totten, Queens, New York.

Ernie Pyle's Published Works

Most Famous Article

"The Death of Captain Waskow" was Pyle's most famous article. It was written in December 1943 and published on January 10, 1944. The National Society of Newspaper Columnists later called it "the best American newspaper column of all time."

Books by Ernie Pyle

Pyle's wartime writings are collected in four books:

- Ernie Pyle In England (1941)

- Here Is Your War (1943)

- Brave Men (1944)

- Last Chapter (1949)

A book of his human-interest stories is:

- Home Country (1947)

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Ernie Pyle para niños

In Spanish: Ernie Pyle para niños

| Jewel Prestage |

| Ella Baker |

| Fannie Lou Hamer |