Ferenc Kazinczy facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Ferenc Kazinczy

|

|

|---|---|

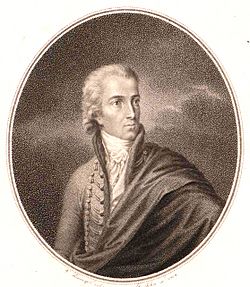

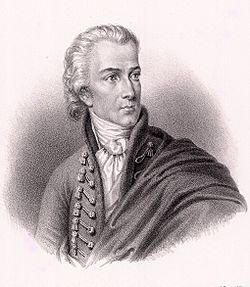

Kazinczy by János Donát, 1812

|

|

| Born | 27 October 1759 Érsemjén, Bihar, Hungary (today Șimian, Romania) |

| Died | 23 August 1831 (aged 71) Széphalom, Zemplén County, Hungary (today part of Sátoraljaújhely) |

| Resting place | Széphalom, Sátoraljaújhely, Borsod-Abaúj-Zemplén County Hungary |

| Occupation | author neologist poet translator notary inspector of education |

| Language | Hungarian |

| Nationality | Hungarian |

| Education | law |

| Alma mater | College of Debrecen (1766) College of Késmárk (1768) College of Sárospatak (1769-1779) |

| Literary movement | Age of Enlightenment Classicism |

| Notable works | Tövisek és virágok (1811) Poétai episztola Vitkovics Mihályhoz (1811) Ortológus és neológus nálunk és más nemzeteknél (1819) |

| Spouse |

Sophie Török

(m. 1804) |

| Children | Iphigenia Eugenia Thalia Márk Emil Ferenc Antal Sophron Ferenc Anna Iphigenia Bálint Cecil Ferenc Lajos |

Ferenc Kazinczy (born October 27, 1759 – died August 23, 1831) was an important Hungarian writer, poet, and translator. He was a key figure in renewing the Hungarian language and literature around the start of the 1800s.

Kazinczy is famous for his work on the Language Reform of the 19th century. During this time, thousands of new words were created or brought back into use. This helped the Hungarian language keep up with new scientific ideas and become the official language of the country in 1844. He is seen as one of the founders of the Hungarian Reform Era, alongside other important writers like Dávid Baróti Szabó and György Bessenyei.

Contents

Life Story

Early Years and Education

Ferenc Kazinczy was born in Érsemjén, a place that was part of the Kingdom of Hungary back then. Today, it is called Șimian and is in Romania. His father, József Kazinczy, came from an old noble family and worked as a judge. His mother was Zsuzsanna Bossányi. Ferenc had eight brothers and sisters.

For the first eight years of his life, he was raised by his grandfather, Ferenc Bossányi. His grandfather was a notary and a parliamentary ambassador. During this time, Ferenc only heard Hungarian spoken.

He started writing letters to his parents in 1764. In 1766, he studied at the College of Debrecen for three months. After that, he learned Latin and German at home from a student. His father, who was well-educated, also taught him and spoke with him in Latin and German. Ferenc continued his language studies at the College of Késmárk (now Kežmarok, Slovakia) in 1768.

His father first wanted Ferenc to become a soldier. But Ferenc was more interested in writing. So, his father then wanted him to be a writer. His father, a religious man, asked Ferenc to translate religious texts from Latin to Hungarian. However, Ferenc preferred reading other books, like plays and novels. He also read poems by famous writers like Vergilius and Horace.

After his father passed away in 1774, Ferenc continued his translations. But his theology teacher told him to stop because the texts were too hard. Ferenc then started focusing on more worldly and national topics. He even wrote a short geography book about Hungary, which was published in Kassa (now Košice, Slovakia) in 1775.

Studying at Sárospatak College

On September 11, 1769, Ferenc became a student at the College of Sárospatak. There, he taught himself Ancient Greek. He studied philosophy and law in his early years. In 1773, he began learning rhetoric, which is the art of speaking or writing effectively. He also learned French from a French soldier.

In 1776, he translated a German short story, Die Amerikaner, into Hungarian. It was published in Kassa with the title Az amerikai Podoc és Kazimir keresztyén vallásra való megtérése (The conversion of American Podoc and Kazimir to the Christian religion). This work introduced him to ideas about religious tolerance. In his translation, Kazinczy used the word világosság (meaning clarity) for the first time in Hungarian.

He was very happy to connect with György Bessenyei, a leading Hungarian author of that time. Kazinczy's uncle, who was part of the county's delegation, took him to Vienna. This trip greatly impressed Kazinczy, especially the city's art collections.

Kazinczy was influenced by writers like Salomon Gessner and Christoph Martin Wieland. He also loved Jean-François Marmontel's Contes Moraux (Moral tales), which he later took with him to prison. This book showed him a new, beautiful style of Hungarian writing. He decided then to become a translator and help improve the Hungarian language.

Starting His Legal Career

After finishing his studies, Kazinczy went to Kassa on September 9, 1779. He worked on his law degree and met his first love, Erzsébet Rozgonyi. He also met Dávid Baróti Szabó, one of his role models.

During his time in Kassa, Kazinczy changed his views on religion. He moved away from strict religious teachings and became more interested in beauty and art. He started translating Salomon Gessner's works around 1780. His translation of Siegwart was published in 1783. He corresponded with famous European scholars like Gessner, which made him feel special.

In 1779, he met Miklós Révai, a grammarian who studied how words are formed in Hungarian. They became good friends and often discussed literature and grammar.

From January 1781 to June 1782, he continued his law practice in Eperjes (now Prešov, Slovakia). Besides work, he enjoyed dancing, playing the flute, drawing, and reading, especially German writers. He also fell in love with an "educated girl" there.

In August 1782, he moved to Pest to continue his law practice. There, he met two older, important authors, Lőrinc Orczy and Gedeon Ráday. Ráday taught him more about Western literature and old Hungarian writers like Miklós Zrínyi. This friendship helped Kazinczy develop his artistic taste. He showed his translations of Gessner's idylls to them, and their praise encouraged his writing dreams.

Kazinczy also became interested in the church policies of Emperor Joseph II. He supported the emperor's policies on religious tolerance and freedom of the press. As a Protestant, he was happy to be close to those who fought for Protestant freedom. He also joined a secret society called Freemasonry in 1784, which supported progress and refinement of society.

Working as an Inspector

In 1783, Kazinczy returned to his mother's home. He then took a job as an honorary clerk and later became a judge in Abaúj County. He also briefly worked as a vice-notary in Zemplén County.

In 1784, he joined the Masonic lodge in Miskolc, thanks to Count Lajos Török, who was a friend and his future father-in-law. As a freemason, Kazinczy met many intellectuals.

In August 1785, he traveled to Vienna to ask for a job as an inspector of county schools. On November 11, he was given this position, which he held for five years. He was known as the "apostle of renewing Hungarian education." He had a good salary and a lot of power. He lived in Kassa and traveled a lot, setting up and checking schools. He started with 79 schools, and this number quickly grew to 124. Nineteen of these were "common schools" where students of different religions could study together with state funding.

He finished his translations of Salomon Gessner's idylls and published them in a book called Gessner Idylliumi in 1788. This book brought him fame abroad. He focused on making the translation accurate and musical.

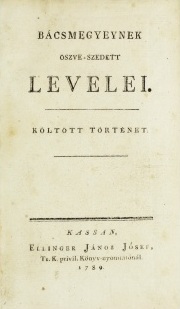

His social life in Kassa and his involvement in Freemasonry refined his emotions. In 1789, he published Bácsmegyeynek öszve-szedett levelei (Collected letters of Bácsmegyey). This was his translation of a German novel, but he changed it to include his friends and their gatherings. This made it a very personal work. It was a great success, but also received criticism from conservative writers.

On November 13, 1787, Kazinczy, along with Dávid Szabó Baróti and János Batsányi, started the Magyar Museum periodical. This was the first literary magazine in Hungarian. However, Kazinczy and Batsányi disagreed on the magazine's direction. Kazinczy wanted a literary magazine with translations and reviews, while Batsányi wanted a more general journal. Their political differences also caused problems. Kazinczy supported Emperor Joseph II, while Batsányi was part of a reform movement. Kazinczy soon left the magazine.

In November 1789, Kazinczy started his own periodical called Orpheus. Only eight issues were published between 1789 and 1792. He wrote essays under the name Vince Széphalmy. His journal struggled because he promoted the ideas of Voltaire and other Freemason philosophers, and it wasn't as popular as Magyar Museum. Both journals eventually closed.

In 1790, the Holy Crown was brought to Hungary. Kazinczy was part of the Crown Guard. During this time, he translated Friedrich Ludwig Schröder's Hamlet and wrote a letter supporting Hungarian acting. He helped organize Hungarian theater in Buda.

After Emperor Joseph II died, the old system changed. The next emperor, Leopold II, closed the "common schools" in 1791, and Kazinczy lost his job because he was not Roman Catholic. He tried to get another job but was unsuccessful.

Productive Years and Arrest

After Emperor Leopold II died, Francis I became emperor. In May 1792, Kazinczy became an envoy in the Lower Chamber of the National Assembly in Buda. He tried to get a secretary position but it was already taken.

After the assembly, Kazinczy returned home and worked in Alsóregmec for about a year and a half until 1794. This was a very productive time for him. He published many translated and original works, including Helikoni virágok 1791. esztendőre (Flowers of Helicon for the year 1791), Lanassza (a tragedy), and Sztella (a drama by Johann Wolfgang von Goethe). He also translated works by Gotthold Ephraim Lessing, Friedrich Gottlieb Klopstock, Christoph Martin Wieland, William Shakespeare, and Molière.

Kazinczy felt that some of the good policies of Joseph II were being undone. He criticized the existing system in his translation of Christoph Martin Wieland's Sokrates mainomenos, published in 1793. This book was quickly banned.

He became involved with a movement led by Ignác Martinovics, which aimed for a "bloodless revolution." Kazinczy liked the idea of peaceful change.

Time in Prison

Ferenc Kazinczy was arrested on December 14, 1794, at his mother's house. He was taken to Buda and waited for his judgment in a monastery. On May 8, 1795, he was sentenced to death. For three weeks, he lived knowing he might die. But thanks to his relatives, the emperor changed his sentence to imprisonment for an unknown period.

He stayed in Buda until September 27, then was moved to Brünn (now Brno, Czech Republic) and held in the prison of Špilberk Castle. He was in a damp, underground cell and became very ill. Sometimes, his writing tools were taken away, so he wrote with rust paint or even his own blood. He used a piece of tin from the window as a pen. When he was allowed, he corrected old translations or worked on new ones. Later, his conditions improved, and he was moved to an upper floor where he could have books.

He was moved to other prisons, including Obrowitz (now Zábrdovice, Czech Republic) and Kufstein Fortress. On June 30, 1800, fearing the French army, his captors moved him again, eventually to Munkács (now Mukachevo, Ukraine).

Finally, on June 28, 1801, Kazinczy was granted amnesty by the king and set free. He had spent a total of 2,387 days (about 6 and a half years) in prison. He wrote about this time in his book Fogságom naplója (Diary of my captivity).

Later Life and Family

After his release, other writers welcomed him, but Kazinczy mostly stayed away from public life. His property had been greatly reduced by the costs of his imprisonment. He only had a small grapefield and a hill near Sátoraljaújhely, which he named Széphalom (Nice Hill).

In 1804, he became seriously ill but recovered. In 1806, he settled in Széphalom, where his new house was still being built. He faced constant money problems but found joy in his growing family.

Later, he married Sophie Török, the daughter of his former patron, Count Lajos Török. Sophie was 21 years younger than him and came from a wealthy family. They lived together for almost 27 years, often struggling financially, but their diaries and letters show they were happy.

They had eight children: Iphigenia (who died as a baby), Eugenia, Thalia, Márk Emil Ferenc, Antal Sophron Ferenc, Anna Iphigenia, Bálint Cecil Ferenc, and Lajos. While Kazinczy focused on Hungarian literature, Sophie managed the household and raised their children. She was also known for her knowledge of herbs and home remedies, helping many people during the cholera epidemic of 1831.

Kazinczy's youngest son, Lajos, became a soldier and fought in the Hungarian War of Independence. After the uprising was defeated, he was executed. He is remembered as the Fifteenth Martyr of Arad.

In 1828, Kazinczy helped establish the Hungarian Academy. He died of cholera in Széphalom in 1831.

His Legacy

Kazinczy was known for his beautiful writing style. He was greatly inspired by famous writers like Lessing, Goethe, Shakespeare, and Molière. He also edited the works of other Hungarian poets.

A collection of his works, mostly translations, was published in Pest between 1814 and 1816. His original writings, mainly letters, were published later.

In 1873, a neo-classicistic memorial hall (a mausoleum) and graveyard were built in Széphalom in his memory. It was designed by the architect Miklós Ybl. Today, this site is part of the Ottó Herman Museum, and there are plans to build a Museum of the Hungarian Language there.

Personal Life

On November 11, 1804, Ferenc Kazinczy married Sophie Török, the daughter of his former principal, Count Lajos Török. Sophie was 21 years younger than him and came from a wealthy and important family. Kazinczy felt for a long time that he was not good enough for her. He wrote in his diary about why he chose Sophie: "She is not beautiful, but her eyes are full of soul, her face is full of goodness, her figure is graceful, her voice is lovely, her heart is noble, her mind is educated, her soul is pure, and her character is angelic. "

Sophie married Kazinczy out of love, and her father saw Kazinczy as a friend.

They lived together for almost 27 years. Despite often facing serious money problems, their diaries and letters show they had a happy life together. They had four sons and four daughters. Sadly, their first daughter died as a baby in 1806.

- Iphigenia (1805 - 1806)

- Eugenia (1807 - 1903)

- Thalia (1809 - 1866)

- Márk Emil Ferenc (1811 - 1890)

- Antal Sophron Ferenc (1813 - 1885)

- Anna Iphigenia (1817 - 1890)

- Bálint Cecil Ferenc (1818 - 1873)

- Lajos (1820 - 1849)

While Kazinczy worked to improve Hungarian literature, Sophie focused on their home and raising their children. She also taught the children of their friends. According to Kazinczy's writings, Sophie knew a lot about herbs and making homemade medicines. She was able to help many people during the cholera epidemic of 1831.

Their youngest son, Lajos Kazinczy, became a soldier and an army colonel. He fought bravely in the Hungarian War of Independence of 1848-1849. After the uprising was defeated, he was executed. He is remembered as one of the Martyrs of Arad, a group of Hungarian heroes.

Images for kids

-

First meeting of Ferenc Kazinczy and Károly Kisfaludy in 1828, based on painting by Soma Orlai Petrich

See also

In Spanish: Ferenc Kazinczy para niños

In Spanish: Ferenc Kazinczy para niños