Food history facts for kids

Food history is a cool subject that looks at how food has changed over time. It also explores how food affects our culture, money, environment, and society. It's different from just studying recipes, which is called culinary history.

The first magazine about food history, Petits Propos Culinaires, started in 1979. The very first big meeting on this topic was the Oxford Food Symposium in 1981.

Food and Diets Through Time

Early humans ate what they could find and what tasted good. Humans started as omnivores, meaning they ate both plants and animals. They were hunter-gatherers. What they ate changed a lot depending on where they lived and the weather. People in warm, tropical places ate more plants. Those in colder areas ate more animal products. Studies of ancient human and animal bones show that cannibalism (humans eating other humans) also happened in prehistoric times.

Farming began at different times in different parts of the world, starting about 11,500 years ago. This gave some cultures a lot more grains like wheat, rice, and maize. It also brought us foods like potatoes. From these, staples like bread, pasta dough, and tortillas were created. When humans started to tame animals, some cultures gained access to milk and dairy products.

In 2020, archaeologists found an amazing, well-preserved fast-food counter (called a thermopolium) from 79 AD in Pompeii. It even had 2,000-year-old foods still in its deep clay jars!

Ancient Times

In classical antiquity (ancient Greece and Rome), people ate simple, fresh foods. These foods were usually grown nearby or brought from close areas if there was a shortage.

Middle Ages in Western Europe (5th to 15th Century)

In Western Europe, medieval cuisine (food from the 5th to 15th centuries) didn't change very quickly.

Cereals were the most important food during the early Middle Ages. Poor people ate barley, oats, and rye. Common foods included bread, porridge, and gruel. Fava beans and vegetables were important additions to the grain-based diet of the lower classes. Meat was expensive and a sign of wealth. Wild game was mostly eaten by landowners. The most common meats were pork, chicken, and other domestic fowl. Beef was less common because it needed more land to raise cattle. Cod and herring were key foods for people in the north. Dried, smoked, or salted, they traveled far inland. Many other kinds of saltwater and freshwater fish were also eaten.

What people ate depended on the seasons, where they lived, and religious rules. Most people could only eat what the nearby land and sea provided. Peasants cooked simply, usually over an open fire, in a pot, or on a spit. Their ovens were often outside and made of clay or turf. Poor families mainly ate grains and vegetables in stews, soups, or thick porridges. They also ate anything grown on their small plots of land. They couldn't afford spices. It was also a crime for them to hunt deer, boar, or rabbits. Their main foods included rye or barley bread, stews, local dairy products, cheaper meats like beef, pork, or lamb, fish (if they lived near water), home-grown vegetables and herbs, fruit from local trees, nuts, and honey.

The upper class and nobles had better food than the lower classes. Their meals were often colorful and flavorful, very different from what the poor ate. Noble meals were huge, with many dishes, but people often ate small portions. Their foods were heavily spiced, and many spices were expensive imports from outside Europe. The diet of the upper class included manchet bread, various meats like venison, pork, and lamb, fish and shellfish, spices, cheese, fruits, and a few vegetables.

The Church also controlled food consumption. Many fasts happened throughout the year, with Lent being the longest. On certain days, people couldn't eat meat or fish. This didn't affect the poor much, as they already had limited food choices. The Church also encouraged feasts, like on Christmas and other holidays. Nobles and upper classes enjoyed these grand feasts, often after a fasting period.

16th Century: Spain and Portugal's Influence

The Portuguese and Spanish Empires created sea trade routes that connected food exchange worldwide. Under Phillip II, Catholic food traditions helped change the food in the Americas, and also Buddhist, Hindu, and Islamic foods in Southeast Asia. In Goa, Portugal, people were encouraged to marry local women who had converted to Christianity. This mix led to new dishes combining Portuguese and Western Indian foods. The Portuguese brought round, raised loaves of bread, using wheat shipped from Northern India. They also brought pickled pork. This pork, pickled in wine or vinegar with garlic (called carne de vinha d’alhos), later became vindaloo.

18th Century: Early Modern Europe

Grain and livestock were the most important farm products in France and England for a long time. After 1700, clever farmers tried new ways to grow more food. They also looked into new products like hops, oilseed rape, special grasses, vegetables, fruit, dairy foods, farm-raised poultry, rabbits, and freshwater fish.

Sugar started as a luxury for the rich. But by 1700, Caribbean sugar plantations, worked by African slaves, grew much more sugar. This made sugar widely available. By 1800, sugar was a common food for working-class families. For them, it showed growing economic freedom and status.

Workers in Western Europe in the 18th century ate bread and gruel. This was often in a soup with greens and lentils, a little bacon, and sometimes potato or cheese. They drank beer (water was often unsafe) and a bit of milk. About three-quarters of their food came from plants. Meat was much more appealing but very expensive.

19th Century

By 1870, people in Western Europe ate about 16 kilograms of meat per person each year. This rose to 50 kilograms by 1914 and 77 kilograms in 2010. Milk and cheese were rarely eaten. Even in the early 1900s, they were still uncommon in Mediterranean diets.

In the busy immigrant neighborhoods of growing American industrial cities, housewives bought ready-made food. They got it from street sellers, push carts, and small shops run from homes. This made it easy for new foods like pizza, spaghetti with meatballs, bagels, hoagies, pretzels, and pierogies to become popular in America. It also firmly established fast food in the American way of eating.

20th Century

The first half of the 20th century saw two world wars. In many places, this led to food rationing and hunger. Sometimes, starving civilians was even used as a powerful new weapon.

World War I and After

In Germany during World War I, the food rationing system in cities almost completely broke down. People ate animal feed to survive the "Turnip Winter." Conditions in Vienna got worse because the army got priority for food.

In Allied countries, meat first went to soldiers. Then it went to urgent civilian needs in Italy, Britain, France, and Greece. Meat production was pushed to its limits in the United States, Australia, New Zealand, Canada, and Argentina. Shipping across the ocean was tightly controlled by the British. Food shortages were severe in Russian cities, leading to protests that helped overthrow the Tsar in February 1917.

In the first years of peace after the war ended in 1918, most of Eastern and Central Europe faced severe food shortages. The American Relief Administration (ARA) was created under Herbert Hoover, who was America's "food czar" during the war. Its job was to provide emergency food rations across Central and Eastern Europe. The ARA fed millions, including people in Germany and the Soviet Union. After the U.S. government stopped funding the ARA in the summer of 1919, the ARA became a private group. It raised millions of dollars from private donors. Through the ARA, the European Children's Fund fed millions of starving children.

The 1920s brought new foods, especially fruit, transported from all over the world. After World War I, many new food products became available to regular households. Branded foods were advertised for how easy they were to use. Instead of an experienced cook spending hours on difficult custards and puddings, housewives could buy instant foods in jars or powders that mixed quickly. Richer homes now had ice boxes or electric refrigerators. This allowed for better storage and the convenience of buying food in larger amounts.

World War II and After

During World War II, Nazi Germany tried to feed its people by taking food from occupied countries. They also purposely cut off food supplies to Jews, Poles, Russians, and the Dutch.

As part of the Marshall Plan in 1948–1950, the United States shared its technology and money for large-scale, high-production farming in post-war Europe. Poultry was a popular choice. Production grew quickly, prices dropped sharply, and people widely accepted the many ways to serve chicken.

The Green Revolution in the 1950s and 1960s was a big step forward in how much food plants could produce. It increased farm production worldwide, especially in developing countries. Research started in the 1930s, and big improvements in output became important in the late 1960s. These efforts led to new technologies, including:

- new, high-yielding varieties (HYVs) of cereals, especially dwarf wheat and rices

- using chemical fertilizers and special farm chemicals

- controlled water supply (often with irrigation)

- new farming methods, including machines.

All these things together were seen as a "package of practices" to replace older ways of farming.

History of Notable Foods

Potato

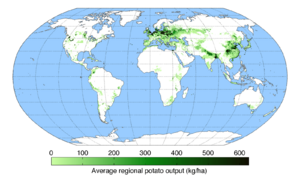

The potato was first grown by people in what is now southern Peru and northwestern Bolivia. Since then, it has spread around the world and become a main crop in many countries.

Some people believe that the potato's arrival was responsible for a quarter or more of the population growth and city development in the Old World (Europe, Asia, Africa) between 1700 and 1900. After the Spanish conquest of the Inca Empire, the Spanish brought the potato to Europe in the second half of the 16th century. This was part of the Columbian exchange, where plants, animals, and cultures were traded between the Old and New Worlds. European sailors then carried the potato to lands and ports all over the globe. Farmers in Europe were slow to trust the potato at first. But soon enough, it became an important main food and farm crop. It played a big part in the European population boom of the 19th century.

However, there wasn't much variety in the types of potatoes brought to Europe. This lack of different genes made the crop easy to get sick. In 1845, a plant disease called late blight, caused by a fungus-like organism, spread quickly through poor communities in western Ireland and parts of the Scottish Highlands. This led to crop failures and the terrible Great Irish Famine. Today, China is the largest potato-producing country, followed by India (as of 2017, according to FAOSTAT).

Rice

Rice comes from the plant Oryza sativa. It has been grown since about 6000 BCE. The main countries that grow rice are in East and South Asia. Where rice first came from is a big debate between India and China, as both countries started growing it around the same time. The amount of rice grown each year is usually between 800 billion and 950 billion pounds. Muslims brought rice to Sicily in the 9th century. After the 15th century, rice spread throughout Italy and then France. Later, it spread to all continents during the age of European exploration. As a grain, it is now the most eaten main food worldwide. Currently, India is the leading rice-producing country, according to FAOSTAT.

Sugar

Sugar came from India. People learned to make it from the sugarcane plant using chemical and mechanical processes. The word "sugar" comes from the Sanskrit word sarkara. Before this, people used to chew sugarcane to enjoy its sweetness. Later, Indians found a way to crystallize the sweet liquid. This method then spread to India's neighboring countries. The Spanish and Portuguese empires provided sugar for Europe by the late 1600s from plantations in the New World. Brazil became the main sugar producer.

Sugar was expensive during the Middle Ages. But as more sugar was grown, it became easier to get and more affordable. This meant Europeans could now enjoy Islamic-inspired sweets that were once too costly to make. The Jesuits were major producers of chocolate. They got it from the Amazon jungle and Guatemala and shipped it worldwide to Southeast Asia, Spain, and Italy. They taught Europeans Mesoamerican ways to process and prepare chocolate. Fermented cocoa beans had to be ground on heated grindstones to prevent oily chocolate, a process new to many Europeans. As a drink, chocolate mostly stayed popular in Catholic countries. This was because the church didn't consider it a food, so it could be enjoyed during fasting. Brazil is currently the largest producer of sugar, followed by India, which is also the largest consumer of sugar.

How Religion Shaped Cuisines

The three most common religions—Christianity, Buddhism, and Islam—developed their own special recipes, cultures, and food practices. All three follow two main ideas about food: "the theory of the culinary cosmos" (how food fits into the universe) and "the principle of hierarchy" (who eats what, and when). There used to be a third idea about sacrifice, but religious and societal views on killing animals for religious reasons have changed over time, so it's not a main principle anymore.

Judaism

Jews have eaten many different kinds of food, often similar to what their non-Jewish neighbors ate. However, Jewish food is shaped by Jewish dietary laws, called kashrut, along with other religious rules. For example, making a fire was forbidden on Shabbat (the Sabbath). This led to the creation of slow-cooked Sabbath stews. Sephardic Jews were forced to leave Spain and Portugal in 1492. They moved to North Africa and Ottoman lands, mixing their Spanish/Portuguese food with local dishes.

Many foods thought of as Jewish in the United States, like bagels, knishes, and borscht, are actually Eastern European Ashkenazi dishes. Non-Jewish people also ate these foods widely throughout Eastern Europe.

Jesuits

The Jesuits' influence on food varied from country to country. They sold maize (corn) and cassava to plantations in Angola, which later provided food for slave traders. They exported sugar and cacao from the Americas to Europe. In southern parts of the Americas, they dried leaves of the local mate plant. This drink competed with coffee, tea, and chocolate as a favorite hot drink in Europe. Despite mate's popularity, the Jesuits were the main producers and promoters of chocolate. Using local workers in Guatemala, they shipped chocolate worldwide to Southeast Asia, Spain, and Italy. Chocolate's popularity was also partly because the church didn't consider it a food, so it could be eaten while fasting. The Jesuits also brought several foods and cooking methods to Japan: deep frying (tempura), cakes and sweets (like kasutera), and bread, which is still called pan (the Iberian name).

Islamic Cuisine in Eurasia

See also

In Spanish: Historia de la gastronomía para niños

| Leon Lynch |

| Milton P. Webster |

| Ferdinand Smith |