Frédéric Chopin facts for kids

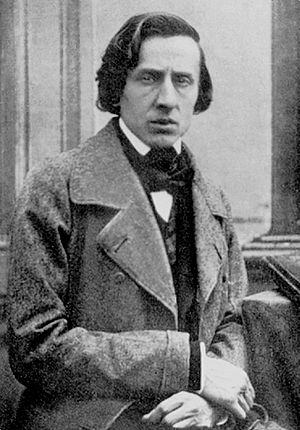

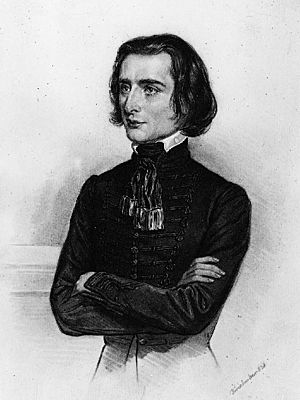

Frédéric François Chopin (born Fryderyk Franciszek Chopin; March 1, 1810 – October 17, 1849) was a famous Polish composer and amazing pianist from the Romantic period. He mostly wrote music for the solo piano. People all over the world still know him as a top musician of his time. His "poetic genius" was built on piano skills that were unmatched by anyone else.

Chopin was born in Żelazowa Wola, in what was then the Duchy of Warsaw. He grew up in Warsaw, which later became part of Poland. He was a child prodigy, meaning he was super talented from a young age. He finished his music education and wrote his first pieces in Warsaw. He left Poland at age 20, just before a big uprising in November 1830. When he was 21, he moved to Paris, France. For the last 18 years of his life, he only gave about 30 public concerts. He preferred playing in smaller, more private gatherings called salons. He made money by selling his music and giving piano lessons, which were very popular. Chopin became friends with the famous composer Franz Liszt and was admired by many other musicians, like Robert Schumann.

He had a difficult relationship with the French writer Aurore Dupin, known as George Sand. A short, unhappy trip to Mallorca with Sand in 1838–39 turned out to be one of his most creative times for composing. In his last years, a fan named Jane Stirling helped him financially. She also arranged for him to visit Scotland in 1848. Chopin was often in poor health throughout his life. He died in Paris in 1849 when he was 39 years old, likely from a heart problem made worse by tuberculosis.

All of Chopin's music includes the piano. Most of his pieces are for solo piano, but he also wrote two piano concertos, some chamber music (music for a small group of instruments), and 19 Polish songs. His piano pieces are very challenging to play and pushed the limits of the instrument. His own performances were known for their delicate details and deep feeling. Chopin's main piano works include mazurkas, waltzes, nocturnes, polonaises, and ballades (which he helped make a popular type of instrumental music). He also wrote études, impromptus, scherzi, preludes, and sonatas. Some of these were published after his death. His style was influenced by Polish folk music, classical composers like Bach, Mozart, and Schubert, and the lively atmosphere of Paris salons. His new ideas in music style, harmony (how notes fit together), and musical form (the structure of music), along with his connection of music to national pride, were very important during and after the Romantic period.

Chopin's music, his fame as one of the first music celebrities, his link to political uprisings, his well-known love life, and his early death have made him a key figure of the Romantic era. His works are still popular today. Many films and books have been made about his life. One of his many memorials is the Fryderyk Chopin Institute in Poland. It was created to study and promote his life and works. This institute also hosts the International Chopin Piano Competition, a very important contest just for his music.

Contents

Chopin's Life Story

Growing Up in Poland

Childhood Days

Fryderyk Chopin was born in Żelazowa Wola. This town is about 46 kilometers (28 miles) west of Warsaw. At that time, it was part of the Duchy of Warsaw, a Polish state created by Napoleon. His baptism record says he was born on February 22, 1810. But Chopin and his family always used March 1 as his birthday, which is now generally accepted.

His father, Nicolas Chopin, was French and moved to Poland when he was 16. He married Justyna Krzyżanowska. She was a distant relative of a family his father worked for. Chopin was baptized in the same church where his parents married. His godfather, Fryderyk Skarbek, was 18 and a student of Nicolas Chopin. Fryderyk was named after him. Chopin was the second child and only son of Nicolas and Justyna. He had an older sister, Ludwika, and two younger sisters, Izabela and Emilia. Emilia died at age 14, probably from tuberculosis. Nicolas Chopin loved his new home, Poland, and made sure everyone in the family spoke Polish.

In October 1810, when Chopin was six months old, his family moved to Warsaw. His father got a job teaching French at the Warsaw Lyceum. The family lived on the school grounds. His father played the flute and violin, and his mother played the piano. She also gave lessons to boys who boarded at their home. Chopin was always a bit small and often got sick, even as a young child.

Chopin might have learned some piano from his mother. But his first professional music teacher was Wojciech Żywny, a Czech pianist. He taught Chopin from 1816 to 1821. His older sister Ludwika also took lessons from Żywny and sometimes played duets with her brother. It quickly became clear that Chopin was a child prodigy. By age seven, he was already giving public concerts. In 1817, he composed two polonaises. His next work, a polonaise from 1821, is his oldest surviving music paper. He dedicated it to Żywny.

In 1817, the Saxon Palace, where the school was, was taken over by the Russian governor. The Warsaw Lyceum moved to the Kazimierz Palace. Chopin and his family moved to a building next to the Kazimierz Palace. During this time, he was sometimes invited to the Belweder Palace. He played piano for the son of the Russian ruler of Poland, Grand Duke Konstantin Pavlovich of Russia. He even composed a march for him. A writer named Julian Ursyn Niemcewicz wrote about "little Chopin's" popularity in 1818.

Chopin's Education

From September 1823 to 1826, Chopin went to the Warsaw Lyceum. He took organ lessons from the Czech musician Wilhelm Würfel in his first year. In the fall of 1826, he started a three-year course with the composer Józef Elsner at the Warsaw Conservatory. He studied music theory, figured bass, and composition. During this time, he kept composing and giving concerts in Warsaw. He was asked to play a new instrument called the "aeolomelodicon" (a mix of piano and mechanical organ). In May 1825, he played his own music and part of a concerto by Moscheles. This successful concert led to an invitation to play for Tsar Alexander I, who was visiting Warsaw. The Tsar gave him a diamond ring. At another concert in June 1825, Chopin played his Rondo Op. 1. This was his first work to be published and was mentioned in a German newspaper, which praised his "wealth of musical ideas."

From 1824 to 1828, Chopin spent his holidays away from Warsaw. In 1824 and 1825, he stayed at Szafarnia with a schoolmate's father. Here, he heard Polish country folk music for the first time. His letters home from Szafarnia were very lively and funny. They made fun of Warsaw newspapers and showed he was also a talented writer.

In 1827, after his youngest sister Emilia died, the family moved from the Warsaw University building. They moved to lodgings across the street from the university, in the Krasiński Palace. Chopin lived there until he left Warsaw in 1830. His parents continued to run their boarding house for male students. Four students who lived there became Chopin's close friends: Tytus Woyciechowski, Jan Nepomucen Białobłocki, Jan Matuszyński, and Julian Fontana. The last two would later join him in Paris.

Chopin was friends with young artists and thinkers in Warsaw. His final Conservatory report in July 1829 said: "Chopin F., third-year student, exceptional talent, musical genius." In 1829, an artist named Ambroży Mieroszewski painted portraits of Chopin's family, including the first known portrait of the composer.

Around early 1829, Chopin met a singer named Konstancja Gładkowska. He felt a strong affection for her, though it's not clear if he ever told her directly. In a letter to Woyciechowski, he mentioned his "ideal," who inspired the slow part of his Concerto. All of Chopin's biographers agree this "ideal" was Gładkowska. After Chopin's farewell concert in Warsaw in October 1830, they exchanged rings. Two weeks later, she wrote him a loving farewell message. After Chopin left Warsaw, they never met again and didn't seem to write to each other.

Chopin's Career and Fame

Early Success and Travel

In September 1828, while still a student, Chopin visited Berlin with a family friend. He enjoyed operas and concerts by famous musicians. In 1829, on another trip to Berlin, he stayed with Prince Antoni Radziwiłł. The Prince was a composer and cellist. For the Prince and his daughter, Chopin wrote his Introduction and Polonaise brillante.

Back in Warsaw that year, Chopin heard Niccolò Paganini play the violin. This inspired him to write a set of variations called Souvenir de Paganini. This experience might have encouraged him to start writing his first Études (1829–32). These pieces explored what his own instrument could do. After finishing his studies, he made his debut in Vienna. He gave two piano concerts and got many good reviews. Some people said he was "too delicate" for those used to loud piano playing. In his first concert, he played his Variations on "Là ci darem la mano", based on a duet from Mozart's opera Don Giovanni. He returned to Warsaw in September 1829. There, he played his Piano Concerto No. 2 for the first time on March 17, 1830.

Chopin's success as a composer and performer opened doors for him in western Europe. On November 2, 1830, he left Poland "into the wide world, with no very clearly defined aim, forever." He went to Austria with his friend Woyciechowski, planning to go to Italy. Later that month, the November 1830 Uprising broke out in Warsaw. Woyciechowski went back to Poland to join the fight. Chopin, now alone in Vienna, missed his homeland. He wrote to a friend, "I curse the moment of my departure." In September 1831, while traveling to Paris, he learned the uprising had been crushed. He wrote in his private journal: "Oh God! ... You are there, and yet you do not take vengeance!" Some historians believe these events helped him become an "inspired national bard" who felt deeply about Poland's past, present, and future.

Life in Paris

When Chopin left Warsaw in November 1830, he wanted to go to Italy. But there was too much trouble there, so he chose Paris instead. It was hard to get a visa from the Russian authorities, but he finally got permission to pass through Paris on his way to London. He joked that he was only in Paris "in passing." Chopin arrived in Paris on October 5, 1831. He never returned to Poland, becoming one of many Poles who left their country during the Great Emigration. In France, he used the French versions of his first names. After becoming a French citizen in 1835, he traveled with a French passport. However, Chopin stayed close to his Polish friends in exile and never felt completely comfortable speaking French. His biographer, Adam Zamoyski, says Chopin never saw himself as French, despite his father's background, and always felt Polish.

In Paris, Chopin met many artists and important people. He found many chances to use his talents and become famous. During his years in Paris, he met people like Hector Berlioz, Franz Liszt, Ferdinand Hiller, Heinrich Heine, Eugène Delacroix, and Alfred de Vigny. He also met Friedrich Kalkbrenner, who introduced him to the piano maker Camille Pleyel. This started a long and close relationship between Chopin and Pleyel's pianos. Chopin also knew the poet Adam Mickiewicz, whose poems he set to music as songs. He was often a guest of Marquis Astolphe de Custine, a big fan, and played his music in Custine's salon (a social gathering).

Two Polish friends in Paris were also very important to Chopin. Julian Fontana, a fellow student from Warsaw, became Chopin's "general helper and copyist." Albert Grzymała, a wealthy financier in Paris, often advised Chopin and became like an "elder brother" to him.

On December 7, 1831, Chopin received a huge compliment from a famous musician. Robert Schumann, reviewing Chopin's Op. 2 Variations, wrote: "Hats off, gentlemen! A genius." On February 25, 1832, Chopin gave his first Paris concert. It was held in the "salons de MM Pleyel" and everyone admired it. A critic wrote: "Here is a young man who... has found... an abundance of original ideas of a kind to be found nowhere else..." After this concert, Chopin realized his quiet piano style was not best for large concert halls. Later that year, he met the wealthy Rothschild banking family. Their support opened doors for him to other private salons. By the end of 1832, Chopin was a part of the top musical group in Paris. He earned the respect of other musicians like Hiller, Liszt, and Berlioz. He no longer needed money from his father. In the winter of 1832, he started making a lot of money from publishing his works and teaching piano to rich students from all over Europe. This meant he didn't have to give public concerts, which he didn't like.

Chopin rarely performed in public in Paris. In later years, he usually gave only one concert a year at the Salle Pleyel, a hall that held three hundred people. He played more often at salons but preferred playing in his own Paris apartment for small groups of friends. A music historian noted that Chopin was unique because he became so famous with very few public performances—only about thirty in his whole life. The list of musicians who played in his concerts shows how rich Parisian artistic life was. For example, on March 23, 1833, Chopin, Liszt, and Hiller played a concerto by J. S. Bach for three pianos. On March 3, 1838, Chopin and his students played a special arrangement of Beethoven's 7th symphony for eight hands (four pianists). Chopin also helped compose Liszt's Hexameron, writing the sixth variation. Chopin's music quickly became popular with publishers. In 1833, he signed a deal with Maurice Schlesinger, who arranged for his music to be published in France, Germany, and England.

In spring 1834, Chopin went to a music festival in Aix-la-Chapelle with Hiller. There, Chopin met Felix Mendelssohn. After the festival, the three visited Düsseldorf. They had a "very agreeable day," playing and talking about music. In 1835, Chopin went to Carlsbad and spent time with his parents. It was the last time he would see them. On his way back to Paris, he met old friends from Warsaw, the Wodzińskis. He had met their daughter Maria five years earlier when she was eleven. This meeting made him stay for two weeks in Dresden. Maria, now sixteen, painted a portrait of Chopin, which is considered one of the best pictures of him. In October, he finally reached Leipzig, where he met Schumann and Mendelssohn. Mendelssohn thought he was "a perfect musician." In July 1836, Chopin traveled to Marienbad and Dresden to be with the Wodziński family. In September, he asked Maria to marry him, and her mother generally approved. Chopin then went to Leipzig and gave Schumann his G minor Ballade. At the end of 1836, he sent Maria an album with seven of his songs. The simple thank-you note he got from Maria was the last letter he received from her. Chopin put the letters from Maria and her mother in an envelope, wrote "My sorrow" on it, and kept it in his desk drawer for the rest of his life.

Friendship with Franz Liszt

It's not known exactly when Chopin first met Franz Liszt in Paris. But on December 12, 1831, Chopin wrote that he had met many famous musicians, including Liszt. Liszt was at Chopin's first Paris concert in February 1832. He said: "The most vigorous applause seemed not to suffice to our enthusiasm in the presence of this talented musician, who revealed a new phase of poetic sentiment combined with such happy innovation in the form of his art."

The two became friends and lived close to each other in Paris for many years. They performed together seven times between 1833 and 1841. Their first joint performance was on April 2, 1833, at a benefit concert. They played a piano duet. Their last public performance together was for a charity concert in April 1841.

Even though they respected each other, their friendship was sometimes difficult. Some people believe Chopin was a little jealous of Liszt's amazing piano skills. Liszt dedicated his Op. 10 Études to Chopin. Chopin once wrote that he wished he could play his own studies as well as Liszt did. However, Chopin got annoyed in 1843 when Liszt played one of his nocturnes and added many extra fancy notes. Chopin told him to play the music as written or not at all, which made Liszt apologize. Most biographers say they had little to do with each other after this. But in letters as late as 1848, Chopin still called Liszt "my friend." Some say their romantic lives caused a rift. Some claim Liszt was jealous of his girlfriend's interest in Chopin. Others believe Chopin was worried about Liszt's growing friendship with George Sand.

Relationship with George Sand

In 1836, at a party, Chopin met the French writer George Sand (born Aurore Dupin). She was short, dark-haired, had big eyes, and smoked cigars. At first, Chopin didn't like her, saying, "What an unattractive person la Sand is. Is she really a woman?" However, by early 1837, Maria Wodzińska's mother made it clear that a marriage with her daughter was unlikely. She was probably concerned about Chopin's poor health and rumors about his friendships with other women. Chopin finally put the letters from Maria and her mother in a package and wrote "My Sorrow" on it. Sand, in a letter from June 1838, admitted strong feelings for Chopin. She wondered if she should end her current relationship to start one with him. She asked a friend to find out about Chopin's relationship with Maria Wodzińska, not knowing it was already over.

In June 1837, Chopin secretly visited London with the piano maker Camille Pleyel. He played at a musical party. When he returned to Paris, his relationship with Sand became serious. By the end of June 1838, they were a couple. Sand, who was six years older than Chopin, wrote: "I must say I was confused and amazed at the effect this little creature had on me..." The two spent a difficult winter on Majorca (November 1838 to February 1839). They went there with Sand's two children, hoping to improve Chopin's health and her son Maurice's. They also wanted to escape threats from Sand's former lover. The local people on Majorca were very traditional Catholics. When they found out the couple wasn't married, they became unfriendly, making it hard to find a place to stay. This forced the group to live in an old monastery, which offered little protection from the cold winter.

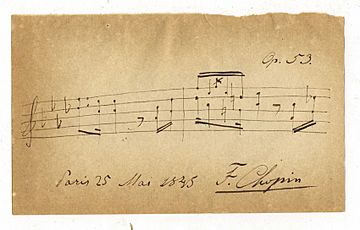

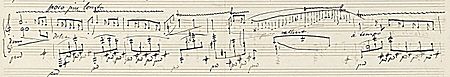

On December 3, 1838, Chopin complained about his bad health and the doctors in Majorca. He joked: "Three doctors have visited me... The first said I was dead; the second said I was dying; and the third said I was about to die." He also had trouble getting his Pleyel piano sent to him. He had to use a local piano for a while. The Pleyel piano finally arrived in December, just before they left the island. Chopin wrote to Pleyel in January 1839: "I am sending you my Preludes [Op. 28]. I finished them on your little piano, which arrived in the best possible condition." While in Majorca, Chopin also worked on his Ballade No. 2, two Polonaises, and the Scherzo No. 3.

Even though this time was productive for his music, the bad weather made Chopin's health worse. Sand decided they had to leave the island. They traveled to Barcelona, then to Marseilles, where they stayed for a few months while Chopin got better. In May 1839, they went to Sand's country home at Nohant for the summer. They spent most of the following summers there until 1846. In autumn, they returned to Paris. Chopin's apartment was close to Sand's rented place. He often visited Sand in the evenings, but they both kept some independence. In 1842, they moved to adjacent buildings in the Square d'Orléans.

During the summers at Nohant, especially from 1839–43, Chopin found peace and composed many works. These included his famous Polonaise in A-flat major, Op. 53. Visitors to Nohant included the painter Delacroix and the singer Pauline Viardot, whom Chopin advised on piano playing and composing.

Chopin's Declining Health

From 1842 onwards, Chopin showed signs of serious illness. After a concert in Paris in February 1842, he wrote that he had to stay in bed all day because his mouth and throat hurt so much. His health continued to get worse. A visitor in 1844 found him "hardly able to move, bent like a half-opened penknife and evidently in great pain."

Chopin composed fewer pieces each year during this time. While he wrote a dozen works in 1841, he wrote only six in 1842 and six shorter pieces in 1843. In 1844, he wrote only one sonata. In 1845, he finished three mazurkas. Although these later works were very refined, his ability to focus was weakening, and his inspiration was troubled by sadness. Chopin's relationship with Sand became strained in 1846 due to problems with her daughter Solange and Solange's fiancé. Chopin often sided with Solange in arguments with her mother. He also faced jealousy from Sand's son Maurice. Also, Chopin didn't care much for Sand's strong political interests.

As Chopin's illness got worse, Sand became more of a nurse to him, calling him her "third child." In letters to others, she expressed her impatience, calling him a "child" and a "sufferer." In 1847, Sand published a novel whose main characters—a rich actress and a sick prince—could be seen as Sand and Chopin. That year, their relationship ended after angry letters. A friend commented, "If [Chopin] had not had the misfortune of meeting G. S. [George Sand], who poisoned his whole being, he would have lived to be Cherubini's age." Chopin died two years later at 39.

Last Tour in Great Britain

Chopin's public popularity as a piano player started to decrease, and he had fewer students. This, along with political problems, made him struggle financially. In February 1848, he gave his last Paris concert with a cellist.

In April, during the 1848 Revolution in Paris, he left for London. There, he performed at several concerts and many parties in grand homes. His Scottish student Jane Stirling and her older sister suggested this tour. Stirling also made all the travel plans and provided much of the money.

In London, Chopin stayed at Dover Street, where a piano company gave him a grand piano. At his first event, the audience included Queen Victoria and Prince Albert. The Prince, who was a talented musician, moved close to the piano to watch Chopin's technique. Chopin was also popular for piano lessons, charging a high fee. He also gave private concerts. At a concert in July, he shared the stage with Viardot, who sang his mazurkas with Spanish words. A few days later, he played for the writer Thomas Carlyle and his wife. In August, he played a concert in Manchester.

In late summer, Jane Stirling invited him to visit Scotland. He stayed at her family's homes. She seemed to want more than just friendship, and Chopin had to make it clear that wasn't possible. He wrote to a friend: "My Scottish ladies are kind, but such bores." He gave public concerts in Glasgow and Edinburgh. In late October 1848, while staying in Edinburgh, he wrote his last will and testament.

Chopin made his last public appearance at London's Guildhall on November 16, 1848. In a final patriotic act, he played for Polish refugees. This was a mistake, as most people were more interested in dancing and refreshments than his piano playing, which tired him out. By this time, he was very ill, weighing less than 45 kg (99 pounds). His doctors knew his sickness was very serious.

At the end of November, Chopin returned to Paris. He spent the winter very ill, but still gave occasional lessons and was visited by friends. Sometimes he played or accompanied singing for his friends. During the summer of 1849, his friends found him an apartment outside the city center. The rent was secretly paid by a fan.

Chopin's Death and Funeral

{{multiple image |align= right |footer=Chopin's death mask, by Auguste Clésinger |width=220 |direction=vertical As his health got worse, Chopin wanted a family member with him. In June 1849, his sister Ludwika came to Paris with her husband and daughter. In September, he moved into an apartment on the Place Vendôme. After October 15, his condition worsened greatly, and only a few close friends stayed with him. A singer joked that "all the grand Parisian ladies considered it a must to faint in his room."

Some friends played music for him when he asked. His sister Ludwika, a priest, Princess Marcelina Czartoryska, Sand's daughter Solange, and his friend Thomas Albrecht were likely present when he died. On October 17, after midnight, the doctor asked if he was suffering much. "No longer," he replied. He died a few minutes before two in the morning. He was 39 years old. Later that morning, Solange's husband made a death mask of Chopin's face and a mold of his left hand.

The funeral was held at the Church of the Madeleine in Paris. It was delayed for almost two weeks until October 30. Only people with tickets could enter, as many were expected. Over 3,000 people arrived without invitations and were turned away.

Mozart's Requiem was sung at the funeral. Chopin's Preludes No. 4 and No. 6 were also played. The funeral procession to Père Lachaise Cemetery was led by Prince Adam Czartoryski. The pallbearers included Delacroix and Camille Pleyel. At the graveside, the Funeral March from Chopin's Piano Sonata No. 2 was played.

Chopin's tombstone shows the muse of music, Euterpe, crying over a broken lyre. It was designed by Solange's husband and put up in 1850. Jane Stirling paid for the monument and for Chopin's sister Ludwika to return to Warsaw. As Chopin wished, Ludwika took his heart back to Poland in 1850. She also took 200 letters from Sand to Chopin, which were later returned to Sand and destroyed.

The cause of Chopin's death has been discussed a lot. His death certificate said tuberculosis. But other ideas have been suggested, like cystic fibrosis. A recent examination of Chopin's preserved heart in 2014 suggested he likely died from a rare case of pericarditis, a heart problem caused by complications of long-term tuberculosis.

Chopin's Music

Music Overview

Over 230 of Chopin's works still exist. Some pieces from his early childhood are lost. All his known works include the piano. Only a few go beyond solo piano music, like his piano concertos, songs, or chamber music.

Chopin learned music from the traditions of Beethoven, Haydn, Mozart, and Clementi. He used Clementi's piano method with his own students. He was also influenced by Hummel's way of playing piano that was both skillful and like Mozart. Chopin said Bach and Mozart were the two most important composers for his musical ideas. Chopin's early works were in the "brilliant" style popular at the time. He was also influenced by Polish folk music and Italian opera. Much of his unique way of adding fancy notes (like his fioriture) came from singing. His melodies increasingly sounded like the music of his home country, sometimes using drones (a continuous low note).

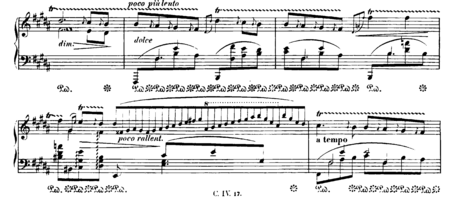

Chopin took the nocturne, a new type of salon music invented by John Field, and made it much more complex and beautiful. He was the first to write ballades and scherzi as separate concert pieces. He also created a new type of music with his own set of preludes (Op. 28, published 1839). He explored the artistic potential of the concert étude (a study piece), which was already being developed by other composers. He did this in his two sets of studies (Op. 10, published 1833, and Op. 25, published 1837).

Chopin also gave popular dance forms a wider range of melody and feeling. Chopin's mazurkas came from the traditional Polish dance, the mazurek. But they were different because they were written for concerts, not for dancing. As one writer put it, "it was Chopin who put the mazurka on the European musical map." His series of seven polonaises (another nine were published after his death) set a new standard for music in that form. His waltzes were also written for salon recitals rather than ballrooms. They are often played faster than their dance versions.

Music Titles and Editions

Some of Chopin's well-known pieces have descriptive names, like the Revolutionary'' Étude (Op. 10, No. 12) and the Minute Waltz (Op. 64, No. 1). However, except for his Funeral March, Chopin never named an instrumental work beyond its type and number. He left it up to the listener to imagine any stories or feelings. The names for many of his pieces were made up by others. There is no proof that the Revolutionary Étude was written about the failed Polish uprising against Russia; it just happened to appear around that time. The Funeral March, the third part of his Sonata No. 2 (Op. 35), was written before the rest of the sonata. No specific event or death is known to have inspired it.

The last opus number Chopin used himself was 65, for his Cello Sonata. He wished on his deathbed that all his unpublished music papers be destroyed. But at the request of his mother and sisters, his musical helper Julian Fontana chose 23 unpublished piano pieces. He grouped them into eight more opus numbers (Opp. 66–73), published in 1855. In 1857, 17 Polish songs Chopin wrote were collected and published as Op. 74.

Works published since 1857 have different catalog numbers instead of opus numbers. The most current list is kept by the Fryderyk Chopin Institute. Chopin's original publishers included Maurice Schlesinger and Camille Pleyel. His works soon appeared in popular piano collections. The first complete collection was published between 1878 and 1902. Modern scholarly editions include the one by Paderewski (1937–1966) and the more recent Polish National Edition, edited by Jan Ekier (1967–2010). The latter is recommended for contestants in the Chopin Competition. Both editions explain their choices and sources in detail.

Chopin published his music in France, England, and Germany because of the copyright laws at the time. So, there are often three different "first editions." Each edition is slightly different because Chopin edited them separately. Sometimes he made changes to the music while editing. Only recently have these differences been more recognized.

Playing Style and Instruments

In 1841, a writer said of Chopin's playing: "One may say that Chopin is the creator of a school of piano and a school of composition. In truth, nothing equals the lightness, the sweetness with which the composer plays the piano; moreover nothing may be compared to his works full of originality, distinction and grace." Chopin didn't believe there was one set way to play well. His style relied a lot on using his fingers very independently. He wrote: "Everything is a matter of knowing good fingering... we need no less to use the rest of the hand, the wrist, the forearm and the upper arm." He also said: "One needs only to study a certain position of the hand... to obtain with ease the most beautiful quality of sound... and [to attain] unlimited dexterity." Because of this approach, Chopin's music often uses the whole keyboard, has parts with double octaves and other chords, quickly repeated notes, grace notes, and different rhythms between the hands (like four notes against three).

Some experts say that today's concert style, which is good for large halls or recordings, doesn't quite match Chopin's more private playing style. Chopin himself told a student that "concerts are never real music, you have to give up the idea of hearing in them all the most beautiful things of art." People who heard him play said he didn't follow strict rules like "always get louder on a high note." Instead, he focused on expressive phrasing, steady rhythm, and delicate coloring. Another composer wrote that Chopin "has created a kind of chromatic embroidery... whose effect is so strange and piquant as to be impossible to describe... virtually nobody but Chopin himself can play this music and give it this unusual turn."

Chopin's music is often played with rubato. This means playing with a flexible tempo, "stealing" time from some notes for expressive effect. There are different ideas about how much rubato is right for his works. Some say Chopin used an older form of rubato where the melody note in the right hand is played slightly after the bass note.

When he lived in Warsaw, Chopin composed and played on a piano made by Fryderyk Buchholtz. Later in Paris, Chopin bought a piano from Pleyel. He thought Pleyel's pianos were the best. Franz Liszt became friends with Chopin in Paris and said the sound of Chopin's Pleyel was like "the marriage of crystal and water." While in London in 1848, Chopin wrote about his pianos: "I have a large drawing-room with three pianos, a Pleyel, a Broadwood and an Erard."

Polish Identity in Music

Chopin is known for bringing a new sense of national pride to music with his mazurkas and polonaises. A composer named Schumann wrote in 1836 that Chopin's music, especially his mazurkas, held a "dangerous enemy" for the Russian ruler, because it showed such strong feelings for Poland. He said, "Chopin's works are cannon buried in flowers!" A biography of Chopin published in 1863 stated that Chopin "must be ranked first among the first musicians... showing the poetic sense of an entire nation."

|

The "Polish character" of Chopin's work is clear; not just because he wrote polonaises and mazurkas... As an artist, he looked for forms that were different from the dramatic music of Romanticism. As a Pole, he showed in his work the deep sadness in his nation's history. He knew he could make his music truly Polish by freeing art from dramatic stories. This way of thinking about "national music"—an inspired solution for his art—is why Chopin's works are understood everywhere outside of Poland... That is the strange secret of his lasting power. |

| Karol Szymanowski, 1923 |

Some modern experts argue against overstating Chopin's role as a "nationalist" composer. They point to earlier composers who used Polish dance forms. Others suggest Chopin's experience with Polish music came more from city versions than from folk music.

However, many agree that Chopin's use of traditional Polish forms like the polonaise and mazurka definitely stirred up national feelings among Poles living across Europe and the world. While some found comfort in his music, others found it a source of strength in their fight for freedom. Even though Chopin's music probably came to him naturally rather than from a conscious patriotic plan, it still came to symbolize the spirit of the Polish people.

Recordings of Chopin's Music

The British Library notes that "Chopin's works have been recorded by all the great pianists of the recording era." The very first recording was in 1895. Many famous pianists have recorded his music. The British Library website has many old recordings by artists like Alfred Cortot, Arthur Rubinstein, and Ignacy Jan Paderewski. Many recordings of Chopin's works are available today. For his 200th birthday, The New York Times critics recommended performances by modern pianists like Martha Argerich, Vladimir Ashkenazy, and Evgeny Kissin. The Warsaw Chopin Society gives out an award for important Chopin recordings every five years.

Chopin in Books, Movies, and TV

Chopin has appeared a lot in Polish literature, both in serious studies of his life and music, and in fictional stories. French writers like Marcel Proust have also written about him. There are many biographies of Chopin in English.

Perhaps the first fictional story about Chopin's life was an opera called Chopin. It was first performed in Milan in 1901. The music was based on Chopin's own works.

Chopin's life and love stories have been made into many films. As early as 1919, a German silent film showed his relationships with three women. The 1945 movie A Song to Remember earned its lead actor an Academy Award nomination for playing Chopin. Other films include Impromptu (1991), starring Hugh Grant as Chopin, and Chopin: Desire for Love (2002).

Chopin's life was also covered in a 1999 BBC documentary and a 2010 documentary for Italian television. A BBC Four documentary in 2010 was called Chopin—The Women Behind The Music.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Frédéric Chopin para niños

In Spanish: Frédéric Chopin para niños

- International Chopin Piano Competition

- The 1st International Chopin Competition on Period Instruments

- Memorials to Frédéric Chopin