Giosafat Barbaro facts for kids

Giosafat Barbaro (born in 1413, died in 1494) was an important person from the Republic of Venice. He belonged to the famous Barbaro family. Giosafat was a diplomat, a merchant (someone who buys and sells goods), an explorer, and a writer who shared his travel stories. He traveled much more than most people during his time.

Contents

Giosafat's Family Life

Giosafat Barbaro was born in a large house called a palazzo in Venice. His parents were Antonio and Franceschina Barbaro. In 1431, he became a member of the Venetian Senate, which was like the government of Venice. In 1434, he married Nona Duodo. They had three daughters and a son named Giovanni Antonio.

Adventures in Tana

From 1436 to 1452, Giosafat Barbaro worked as a merchant. He traveled to Tana, a city located on the Sea of Azov. During these years, a large empire called the Golden Horde was breaking apart because of fights among its leaders.

In November 1437, Barbaro heard about a big mound of earth. People believed it was the burial place of the last king of the Alans, about 20 miles up the Don River from Tana.

Barbaro and six other merchants, some Venetian and some Jewish, hired 120 men. They wanted to dig up this mound, hoping to find treasure. The weather was too bad at first, so they came back in March 1438. They didn't find any treasure. Barbaro carefully wrote down what he saw: layers of earth, coal, ashes, millet, and fish scales. Today, experts believe it wasn't a burial mound at all. It was a huge pile of old kitchen waste that had grown over many centuries! In the 1920s, a Russian archeologist named Alexander Alexandrovich Miller found the remains of Barbaro's digging site.

In 1438, a group called the Great Horde, led by Küchük Muhammad, moved towards Tana. Barbaro went to meet them as a special messenger. He tried to convince them not to attack Tana. Later, Barbaro helped a group of people chase away about a hundred Circassian raiders. Barbaro also visited many cities in the Crimea, like Solcati, Soldaia, Cembalo, and Caffa. He even traveled to Russia, visiting Kazan and Novogorod, which was already under the control of the Muscovites (people from Moscow).

Giosafat Barbaro didn't stay in Tartary for all those years. In 1446, he was chosen for the Council of Forty in Venice. In 1448, he became a Provveditore (a kind of governor) for the trading posts of Modon and Corone in Greece. He served there until he resigned the next year. Since Venice and Tana traded regularly, Barbaro likely went to Tana for business and returned to Venice for the winter. He stopped these trips when the Crimean Khanate became controlled by the Ottoman Turks. Barbaro returned to Venice in 1452, traveling through Russia, Poland, and Germany. In 1455, Barbaro even helped two Tartar men he found in Venice. He gave them a place to stay for two months and then sent them back home to Tana.

Giosafat's Political Work

In 1460, Giosafat Barbaro was chosen to be a Council member for Tana, but he said no to the job. In 1463, he was made Provveditore of Albania. While there, Barbaro fought alongside Lekë Dukagjini and Skanderbeg against the Turks. Provveditore Barbaro joined his soldiers with Dukagjini's and Nicolo Moneta's. They formed a group of 13,000 men to help relieve the Second Siege of Krujë. After Skanderbeg died, Barbaro went back to Venice.

In 1469, Giosafat Barbaro became Provveditore of Scutari in Albania. He led 1200 cavalry (soldiers on horseback) to support Lekë Dukagjini. By 1472, Barbaro was back in Venice. There, he was one of 41 senators who chose Nicolo Tron to be the Doge (the leader of Venice).

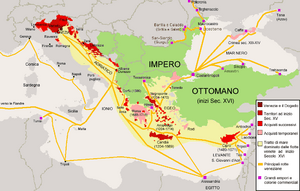

Venice and the Ottoman Turks

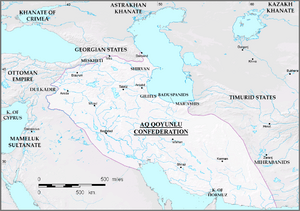

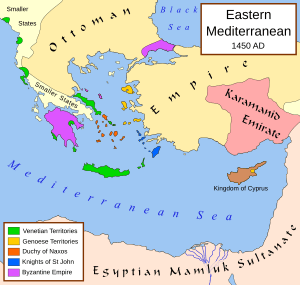

In 1463, the Venetian Senate wanted allies against the Turks. They sent Lazzaro Querini as their first ambassador to Persia. But he couldn't convince Persia to attack the Turks. The ruler of Persia, Uzun Hassan, sent his own messengers to Venice. After the island of Negroponte fell to the Turks, Venice, Naples, the Papal States, the Kingdom of Cyprus, and the Knights of Rhodes all agreed to become allies against the Turks.

In 1471, ambassador Querini returned to Venice with Uzun Hassan's ambassador, Murad. The Venetian Senate decided to send another ambassador to Persia. They chose Caterino Zeno because his wife was the niece of Uzun Hassan's wife. Zeno was able to convince Hassan to attack the Turks. Hassan was successful at first. However, none of the western powers attacked at the same time, and the war turned against Persia.

Ambassador to Persia

In 1472, Giosafat Barbaro was also chosen to be an ambassador to Persia. This was because he had experience in the Crimea, Muscovy, and Tartary. He also spoke Turkish and a little Persian. Barbaro was given ten men to travel with him and a yearly salary of 1800 ducats (a type of money). He was told to encourage Admiral Pietro Mocenigo to attack the Ottomans. He also had to try to get the Kingdom of Cyprus and the Knights of Rhodes to help with their ships. He was also in charge of three ships full of cannons, bullets, and soldiers to help Uzun Hassan.

In February 1473, Barbaro and the Persian messenger, Haci Muhammad, left Venice. They traveled to Zadar, where they met people from Naples and the Pope's court. From there, Barbaro and the others went through Corfu, Modon, Corone, reaching Rhodes and then Cyprus. Barbaro was delayed in Cyprus for a year.

The Kingdom of Cyprus was in a very important location off the coast of Anatolia. It was key for supplying not only Uzun Hassan in Persia but also Venice's allies, Caramania and Scandelore. The Venetian fleet, led by Pietro Mocenigo, protected the supply routes to them. King James II of Cyprus had tried to make allies with Caramania and Scandelore, and also with the Sultan of Egypt, against the Turks. King James had also written to the Venetian Senate, saying they needed to support Persia against the Turks. His navy had even worked with Admiral Mocenigo to take back the coastal towns of Gorhigos and Selefke.

The ruler of Scandelore was defeated by the Turks in 1473, even with military help from Cyprus. The power of Caramania was also broken. King James II of Cyprus privately told Giosafat Barbaro that he felt trapped between two powerful enemies: the Ottoman Sultan and the Egyptian Sultan. The Egyptian Sultan was James's overlord and was not friendly with Venice.

King James II started talking with the Turks. At first, he refused to let the Venetian ships with their weapons land in the port of Famagusta. When Barbaro and the Venetian ambassador, Nicolo Pasqualigo, tried to change James II's mind, the King threatened to destroy the ships and kill everyone on board.

King James II of Cyprus died in July 1473. He left his wife, Queen Catherine, as a pregnant widow. James had chosen a seven-person council. This council included Andrea Cornaro, a relative of the Queen from Venice, and also Marin Rizzo and Giovanni Fabrice, who were agents from Naples and against Venetian influence. Queen Catherine gave birth to a son, James III, in August 1473. Admiral Pietro Mocenigo and other Venetian officials were his godfathers.

Once the Venetian fleet left, there was a revolt by people who supported Naples. This led to the deaths of the Queen's uncle and cousin. The Archbishop of Nicosia, Juan Tafures, the Count of Tripoli, the Count of Jaffa, and Marin Rizzo took control of Famagusta. They captured the Queen and the newborn King.

Barbaro and Bailo Pasqualigo were protected by the Venetian soldiers who had come with Barbaro. The people who started the revolt tried several times to get Barbaro to hand over the soldiers' weapons. The Constable of Cyprus sent a messenger. The Count of Tripoli, the Archbishop of Nicosia, and the Constable of Jerusalem visited in person. After talking with Bailo Pasqualigo, they decided to disarm the men but keep the weapons. Barbaro warned the captains of the Venetian ships in the harbor. Barbaro also sent messages to the Senate of Venice, telling them what was happening. Later, Barbaro and the Venetian soldiers moved to one of the ships.

By the time Admiral Mocenigo returned to Cyprus, the rebels were fighting among themselves. The people of Nicosia and Famagusta had also risen up against them. The uprising was stopped. The leaders who didn't run away were executed. Cyprus then became a state controlled by Venice. The Venetian Senate allowed the soldiers and military equipment that came with Giosafat Barbaro to stay in Cyprus.

Giosafat Barbaro was still in Cyprus in December 1473. The Venetian Senate sent him a letter, telling him to finish his journey. They also sent another ambassador, Ambrogio Contarini, to Persia. Barbaro and the Persian messenger left Cyprus in February 1474. They pretended to be Muslim pilgrims. The messengers from the Pope and Naples did not go with them. Barbaro landed in Caramania. The King there warned them that the Turks controlled the land they needed to travel through. After landing in Cilicia, Barbaro's group traveled through Tarsus, Adana, Orfa, Merdin, Hasankeyf, and Tigranocerta.

In the Taurus Mountains of Kurdistan, bandits attacked Barbaro's group. He escaped on horseback, but he was hurt. Several people in his group, including his secretary and the Persian ambassador, were killed. Their belongings were stolen. As they got closer to Tabriz, Barbaro and his interpreter were attacked by Turcomans. This happened after they refused to give a letter to Uzun Hassan. Barbaro and his remaining friends finally reached Hassan's court in April 1474.

Even though Barbaro got along well with Uzun Hassan, he couldn't convince the ruler to attack the Ottomans again. Soon after, Hassan's son, Ogurlu Mohamed, started a rebellion and took the city of Schiras.

Barbaro visited the old ruins of Persepolis. He wrongly thought they were from Jewish times. He also visited Tauris, Soldania, Isph, Cassan, Como (Kom), Yezd, Shiraz, and Baghdad. Giosafat Barbaro was the first European to visit the ruins of Pasargadae. There, he believed the local story that the tomb of Cyrus the Great belonged to King Solomon’s mother.

The other Venetian ambassador, Ambrosio Contarini, arrived in Persia in August 1474. Uzun Hassan decided that Contarini would return to Venice with a report. Giosafat Barbaro would stay in Persia.

Coming Back to Venice

Barbaro was the last Venetian ambassador to leave Persia. This happened after Uzun Hassan died in 1478. By this time, only one person from Barbaro's group was left. While Hassan's sons fought each other for the throne, Barbaro hired an Armenian guide. He escaped through Erzerum, Aleppo, and Beirut. Barbaro reached Venice in 1479. There, he had to defend himself against complaints that he had spent too much time in Cyprus before going to Persia. Barbaro's report included not just political and military information, but also details about Persian farming, trade, and customs.

Giosafat Barbaro served as Captain of Rovigo and Provveditore of all Polesine from 1482 to 1485. He was also one of the advisors to Doge Agostino Barbarigo. He died in 1494 and was buried in the Church of San Francesco della Vigna.

Giosafat's Writings

In 1487, Barbaro wrote down his travel experiences. In his book, he mentioned that he knew about the travel stories of Niccolò de' Conti and John de Mandeville.

Barbaro's travel account was called "Viaggi fatti da Vinetia, alla Tana, in Persia" (Journeys from Venice to Tana and Persia). It was first published between 1543 and 1545. It was also included in Giovanne Baptista Ramusio's 1559 "Collection of Travels" under the title "Journey to the Tanais, Persia, India, and Constantinople." A scholar named William Thomas translated this work into English for the young King Edward VI. This English version was called ‘’Travels to Tana and Persia’’ and also included the story of Barbaro’s fellow ambassador to Persia, Ambrogio Contarini. This book was published again in London in 1873 by the Hakluyt Society. A Russian version was published in 1971. In 1583, Barbaro’s account was published by Filippo Giunti in ‘’Volume Delle Navigationi Et Viaggi’’ along with the writings of Marco Polo and Kirakos Gandzaketsi’s story of the travels of Hethum I, King of Armenia. In 1601, Barbaro’s and Contarini’s accounts were included in Pietro Bizzarri’s ‘’Rerum Persicarum Historia’’ along with other accounts. In 2005, Barbaro’s account was also published in Turkish as ‘’Anadolu'ya ve İran'a seyahat’’ (Travel to Anatolia and Iran).

Barbaro's account gave more details about Persia and its resources than Contarini's. He was very good at observing new places and writing about them. Much of what Barbaro wrote about the Kipchak Khanate, Persia, and Georgia cannot be found in any other historical records.

Giosafat Barbaro's messages to the Venetian Senate were collected by Enrico Cornet and published as Lettere al Senato Veneto (Letters to the Venetian Senate) in 1852. Barbaro also talked about his travels in a letter he wrote in 1491 to the Bishop of Padua, Pietro Barocci.

|

See also

In Spanish: Giosafat Barbaro para niños

In Spanish: Giosafat Barbaro para niños

| Sharif Bey |

| Hale Woodruff |

| Richmond Barthé |

| Purvis Young |