Government in Anglo-Saxon England facts for kids

Government in Anglo-Saxon England explains how England was ruled from the 5th century until 1066, when the Norman Conquest happened. This period is known as the Anglo-Saxon period. We will look at how small kingdoms grew and then joined together under the Kingdom of Wessex. Then, we'll see how the government worked in the united Kingdom of England.

Contents

How Early Kingdoms Were Ruled (400–871)

The First Small Kingdoms

The way Anglo-Saxon England was governed came from old Germanic laws and traditions. Unlike some other Germanic tribes, the Angles, Saxons, and Jutes who came to Britain had not been much influenced by the Roman Empire. So, Roman laws only started to affect them after they became Christian in the 7th century.

In the 5th and 6th centuries, the Anglo-Saxons moved to Britain and set up farming villages. At first, powerful warriors led family groups. But slowly, small kingdoms began to form in the 6th century. The most important of these were the Heptarchy: Kent, Essex, Wessex, Sussex, East Anglia, Mercia, and Northumbria. The word for king in Old English was cyning. Kingship usually passed down through royal families who believed they were related to a god, often Woden. After they became Christian, royal families linked their origins to biblical genealogies.

Choosing a King

When a king died, a group of "wise men" called the witan (who were important church leaders and nobles) chose the next king. They picked from the ruling family. Things like the candidate's age, skills, popularity, and the old king's wishes all mattered. A king needed to be old and strong enough to lead an army. Sometimes, kings would even retire to monasteries if they could no longer fight. This meant that the oldest son didn't always become king. Younger sons were often passed over for older brothers.

Kings were not always kings for life. The witan could even remove a king. For example, King Sigeberht was removed by the witan in 757. Several kings in Northumbria were also removed by councils.

The King's Power and Laws

A king had the power to make laws and give judgments, but he usually asked his witan for advice. He would act as a judge in the royal court. This court could sentence free people to death, enslavement, or make them pay money. Sometimes, the witan could even change the king's decisions. For instance, in 840, the Mercian witan decided that King Berhtwulf had wrongly taken land from a bishop. The bishop got his land back, and the king gave gifts to the church.

Becoming Christian led to the first written laws, like the Law of Æthelberht in Kent. These early laws tried to keep the peace and stop blood feuds (when families fought each other in revenge).

Kings were very important in bringing Christianity to their kingdoms. After that, they stayed involved in church matters. Kings would call and lead church meetings called synods. At the 664 Synod of Whitby, King Oswiu of Northumbria decided his kingdom would follow the Roman way of calculating the date of Easter, not the Celtic way. The church used its own laws, called canon law, which were based on Roman civil law.

Defending the Kingdom

All free men had the right to carry weapons. They also had a duty to defend the kingdom by serving in the fyrd, which was the army. The king's own group of warriors, called the comitatus, was the main part of the army. Serving in the fyrd was one of the "three necessities" (trinoda necessitas). The other two were repairing burhs (forts) and fixing bridges, which were important for travel.

Local Leaders

Kingdoms had different ways of dividing up land for administration. In Wessex, they had shires. In Kent, they had lathes. In Sussex, they had rapes. In the 8th century, the term ealdorman appeared. In Wessex, ealdormen were royal officials who led the army and made judgments in a shire. They got part of the money from court fines. Sometimes, they were given land for their service. Some ealdormen were even former kings who now ruled smaller areas.

Before the 8th century, one king was sometimes called the bretwalda (meaning "wide-ruler" or "ruler of Britain"). This title meant they had some power over other kingdoms, like influencing the church, leading armies against the native Britons, and collecting tribute.

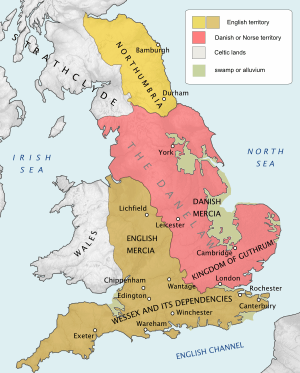

The power of the kingdoms changed over time. Northumbria was strong from 654 to 685. The 8th century was dominated by Mercia. Then, Wessex became the strongest in the 820s under King Ecgberht. In the 860s and 870s, Vikings conquered half of England. This area became known as the Danelaw. The kings of Wessex led the Anglo-Saxon fight against the Vikings and formed the united Kingdom of England.

Unification Under Alfred the Great (871–899)

In the 850s, Viking invaders arrived in England. Their large army, called the Great Heathen Army, conquered most Anglo-Saxon kingdoms. But Alfred the Great (who reigned from 871 to 899) and his kingdom of Wessex successfully fought them off. In 878, Alfred defeated a Viking army led by Guthrum. Around 886, Alfred and Guthrum made a peace agreement, the Treaty of Alfred and Guthrum. This treaty set the borders for the Danelaw. Alfred then gained control over all the English lands not under Viking rule, including London.

Because of the Viking attacks, the government in Wessex became much more organized and effective. Alfred made his kingdom's military stronger. He built over 30 burhs (fortifications), and some of these grew into permanent towns. Alfred gave each burh a certain amount of land (called hides) to help pay for its upkeep and support. This was written down in a document called the Burghal Hidage.

Under Alfred, there were usually nine or ten ealdormen. Each shire in Wessex had one ealdorman, and Kent had two. An ealdorman was in charge of the army, the forts, and collecting taxes in his shire. They were given land and special rights, like getting a third of the profits from the shire court. After Alfred's time, the number of ealdormen decreased.

Royal reeves (also called praepositi) looked after royal lands. They were responsible for managing money and people.

How the Royal Government Worked

Who Became King?

From 899 to 1016, a direct descendant of Alfred the Great from the House of Wessex ruled England. From 1016 to 1042, Danish kings from the House of Knýtlinga held the throne. Edward the Confessor (who reigned from 1042 to 1066) briefly brought the House of Wessex back to power. But in 1066, Harold Godwinson became king, followed by William the Conqueror.

In theory, the people had a say in choosing their king. A church leader named Ælfric of Eynsham explained it like this: "No one can make himself king. The people choose who they want as king. But once he is crowned, he rules over them, and they cannot get rid of him."

Only descendants of Cerdic, the first West Saxon king, could become king. By the 10th century, only sons of kings were considered eligible. These sons were called æthelings. But there were no strict rules about which son would be next. This often caused problems when a king died.

Sons usually followed their fathers, but older relatives could become king instead of very young sons. For example, Edmund I (reigned 939–946) was followed by his brother Eadred (reigned 946–955) because Edmund's sons were too young. Edmund's son Eadwig (reigned 955–959) became king after his uncle, who had no children, died.

At their coronations, kings made a three-part promise: to protect the church, punish criminals, and be fair to all Christian people. This promise later became the basis for important documents like Magna Carta. After the oath, kings were anointed with holy oil. This anointing made kings special, almost like priests. An anointed king was seen as chosen by God, so a bad king was thought to be God's punishment for sins.

In the 10th century, coronations usually happened at Kingston upon Thames. Edward the Confessor was crowned at Winchester. In 1066, Harold Godwinson was crowned at the new Westminster Abbey. This became the usual place for future kings to be crowned.

The King's Household and Court

The king's household and court were the heart of the Anglo-Saxon government. They handled the daily tasks of ruling. England did not have a fixed capital city yet, though Winchester and London were important. The king's household and court moved around. Kings traveled constantly through southern England (where most royal lands were) and less often to the north.

The household included the king's immediate family, like the queen and the æthelings. Important nobles and churchmen served at court regularly. Many would serve in turns as the king visited different areas. But a core group stayed with the king almost all the time. There were important officers like discthegns (who served food) and birele (who served drinks). Many priests worked in the royal chapel.

Inside the chapel was a writing office. This office created important documents like charters, writs, royal letters, and other official papers. Charters, or "landbooks," were written in Latin. They recorded when the king gave land to the church or to individuals. A writ was a short letter from the king with instructions for an official. It had a seal hanging from it to prove it was real. Writs were more efficient than traditional charters. Literate priests and clerks worked in this office. By the time of Edward the Confessor, they were in charge of the Great Seal of the Realm, which was used to make writs official. Serving in the royal chapel could lead to becoming a bishop.

It's not clear when the English treasury (where money was kept) fully developed. Before 1066, there wasn't a single treasurer. But certain officials in the royal chamber or wardrobe were responsible for money matters at different times. By the 11th century, the royal treasure was kept at Winchester.

The King's Justice

In legal matters, the king had the final say over all free people. They had the right to appeal to the royal court. In the 10th century, legal processes became more organized. Certain crimes were only handled by the king's court. These included breaking the king's protection (mund), murder, treason, arson, and not serving in the army.

Kings and shire courts could declare someone an outlaw. This meant they lost legal protection.

The Witan: King's Council

To keep his power, kings relied on the important men of the kingdom: ealdormen, thegns (nobles), bishops, and abbots. But it was hard for kings to keep an eye on all these officials, even with a traveling court. It was easier to call these important men to royal councils, known as the witan or "wise men." The witan was a meeting of the king and his nobles. There was no fixed number of members. Some witans could have a hundred people, while others had only a few. If English kings claimed power over their Welsh neighbors, Welsh kings might also attend. Important church leaders were often there, but not always.

Any major government action would happen in a witan. This included announcing the king's will or making new laws. Charters granting land would be made official in witans. Witans also dealt with church matters and could be very similar to church synods. When a king died, the witan formally elected a new king. Even if the decision was already made, the witan still had to agree. If a king gained power by conquering, he made sure the witan approved.

The witan mostly discussed and advised the king. They talked about many things, including money and legal issues. Discussions happened in the English language. If someone refused to appear before a witan, they could face big fines or even be declared an outlaw.

Money and Taxes

The Anglo-Saxon coinage was considered the best in Europe. Only the king had the right to make coins. King Æthelstan ordered every burh (fortified town) to have a mint. By the time of Edward the Confessor, there were 70 mints. The government kept strict control over the quality and design of the coins. Moneyers (people who made coins) had to use official coin dies. They faced harsh punishments for making fake money. During this time, only the silver penny was used as money. Shillings, pounds, and marks were just ways to count money, not actual coins.

Anglo-Saxon kings traditionally received payments of food. By the 10th century, these payments became less important than the geld, which was a land tax based on hidage (how much land someone owned). There were different types of geld. After Viking attacks started again in the 980s, English kings used the Danegeld to pay tribute to the Vikings. Later, after England was conquered by the Danish prince Cnut the Great, he introduced the heregeld. This tax was used to pay soldiers and sailors. The heregeld was stopped in 1049 by Edward the Confessor. He gave the job of naval defense to the Cinque Ports (a group of coastal towns) in exchange for special rights. The geld continued to be collected every year at a normal rate of 2 shillings per hide for the rest of the Anglo-Saxon period.

How Local Government Worked

England was divided into shires (which are like today's counties). An ealdorman (later called an earl) was in charge of each shire. Twice a year, a shire court met with the ealdorman and the bishop. Shires were further divided into hundreds. The hundred court met once a month. All men within a hundred were organized into tithings (groups of ten families).

Boroughs (towns) were separate from the hundreds and had their own meetings. These were called burghmoot, portmanmoot, or husting. London's Court of Husting had the same power as a shire court. London was divided into wards. The smallest unit of land was the tun (which the Normans later called a vill).

For more information on how Anglo-Saxon courts worked, see Anglo-Saxon law.

| Janet Taylor Pickett |

| Synthia Saint James |

| Howardena Pindell |

| Faith Ringgold |