Great Dayton Flood facts for kids

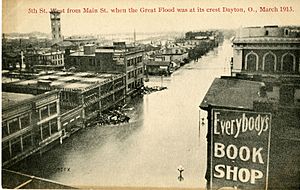

Main Street in Dayton, Ohio, during the flood

|

|

| Date | 21 March 1913–26 March 1913 |

|---|---|

| Location | Dayton, Ohio, and other cities in the Great Miami River watershed |

| Deaths | est. 360 |

| Property damage | $100,000,000 |

The Great Dayton Flood of 1913 was a huge flood caused by the Great Miami River overflowing its banks. It hit Dayton, Ohio, and nearby areas, becoming the worst natural disaster in Ohio's history. This flood led to big changes in how floods are controlled.

After the flood, Ohio's government created a special law called the Vonderheide Act. This law allowed for the creation of "conservancy districts." These districts are special groups that manage rivers and prevent floods. The Miami Conservancy District, which covers Dayton and its surroundings, was one of the very first major flood control groups in Ohio and the United States.

The flood happened in March 1913 because of very heavy winter rainstorms across the Midwest. In just three days, between 8 and 11 inches (200–280 mm) of rain fell. The ground was already soaked, so most of the rain ran straight into the Great Miami River and its smaller streams. The river's walls, called levees, broke. Downtown Dayton was flooded with water up to 20 feet (6.1 m deep). This flood is still the biggest flood ever recorded for the Great Miami River area. The amount of water that flowed through the river during this storm was like the entire monthly flow of Niagara Falls!

The Great Miami River area covers almost 4,000 square miles (10,000 km2). It has 115 miles (185 km) of river channel that flows into the Ohio River. Other cities in Ohio also had flooding from these storms. But none were as badly hit as Dayton, Piqua, Troy, and Hamilton, all located along the Great Miami River.

Contents

Why Dayton Flooded Easily

Dayton was built where the Great Miami River meets three other rivers: the Stillwater River, the Mad River, and Wolf Creek. The main part of the city grew up very close to where these rivers meet. When Israel Ludlow first planned Dayton in 1795, the local Native Americans warned him about floods happening often.

Before the 1913 disaster, the Dayton area had major floods almost every 20 years. Big floods happened in 1805, 1828, 1847, 1866, and 1898. Most of downtown Dayton was built right on the river's natural flood plain. This seemed like a good idea back then because cities relied on rivers for travel and trade.

The storms that caused the 1913 flood lasted several days. They affected many states, especially in the Midwest and along the Mississippi River. Heavy rain and snow made the ground very wet. This led to widespread flooding, known as the Great Flood of 1913, across Indiana, Ohio, Kentucky, New York, and Pennsylvania.

How the Flood Unfolded

Here's a timeline of what happened in Dayton between March 21 and March 26, 1913:

Friday, March 21, 1913

- A storm arrived with strong winds. The temperature was around 60°F (16°C).

Saturday, March 22, 1913

- It was sunny for a while. Then, a second storm came, dropping temperatures to the 20s°F (around -5°C). This made the ground freeze briefly in the morning before thawing later.

Sunday, March 23, 1913 (Easter Sunday)

- A third storm brought heavy rain to the entire Ohio River valley. Since the ground was already soaked, almost all the rain became runoff. This water flowed into the Great Miami River and its smaller streams.

Monday, March 24, 1913

- 7:00 am—After a day and night of heavy rains (8 to 11 inches or 200–280 mm), the river reached its highest level for the year at 11.6 feet (3.5 m). It kept rising.

Tuesday, March 25, 1913

- Midnight—Dayton police were warned that the Herman Street levee was getting weak. They started warning sirens and alarms.

- 5:30 am—City engineer Gaylord Cummin reported that water was at the top of the levees. Water was flowing at an amazing 100,000 cubic feet per second (2,800 m3/s).

- 6:00 am—Water began to overflow the levees and stream along the city streets.

- 8:00 am—Levees on the south side of downtown broke. Flooding began in the city center.

- Water levels continued to rise all day.

Wednesday, March 26, 1913

- 1:30 am—The floodwaters reached their highest point, up to 20 feet (6.1 m) deep in downtown.

- Later that morning, a gas explosion happened downtown. It was near 5th Street and Wilkinson. The explosion started a fire that destroyed most of a city block. Broken gas lines caused several fires across the city. Firefighters could not reach the fires because of the deep water, so many more buildings were lost.

Helping Those Affected

Ohio Governor James M. Cox sent the Ohio National Guard to help protect people and property. The Guard also helped with the city's recovery. They couldn't reach Dayton for several days because of high water everywhere. They set up camps with tents to shelter people who had lost their homes or couldn't go back to them.

The first way to get into the city was by the Dayton, Lebanon and Cincinnati Railroad and Terminal Company train line. It was the only one not affected by the flood.

Governor Cox asked the state government to give $250,000 for emergency help. He also announced that banks would be closed for 10 days. When President Woodrow Wilson asked how the federal government could help, Governor Cox asked for tents, food, supplies, and doctors. Governor Cox also contacted the American Red Cross for help in Dayton and other communities. The Red Cross sent agents and nurses to 112 of Ohio's hardest-hit areas, especially those along major rivers.

Many flood victims went to the National Cash Register (NCR) factory. John H. Patterson, the company's president, and his workers helped flood victims and rescue teams. NCR employees built almost 300 flat-bottomed rescue boats. Patterson organized rescue teams to save thousands of people stuck on roofs and upper floors of buildings. He turned the NCR factory into an emergency shelter, offering food and beds. He also brought in local doctors and nurses to provide medical care.

NCR's buildings became the main base for the American Red Cross and Ohio National Guard rescue efforts. They provided food, shelter, a hospital, medical staff, and even a temporary morgue. The company's grounds became a temporary camp for people who lost their homes. Patterson also gave news reporters and photographers food, lodging, and access to equipment to send their stories. When the Dayton Daily News printing presses stopped working, they used NCR's printing press. This helped Dayton and NCR get news coverage on major news wires.

Damage and Losses

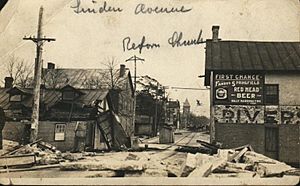

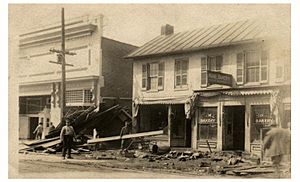

Once the water went down, the damage in Dayton was clear:

- More than 360 people died.

- Nearly 65,000 people had to leave their homes.

- About 20,000 homes were destroyed.

- Many buildings were moved off their foundations. Debris in the moving water also damaged other structures.

- The total damage to homes, businesses, factories, and railroads was estimated at over $100 million in 1913 money.

- Almost 1,400 horses and 2,000 other farm animals died.

Cleaning up and rebuilding took about a year. The economic effects of the flood took almost a decade to recover from. Because of the flood, many old and historic buildings in downtown Dayton were lost. This is why the city center looks more like newer cities in the western United States.

One person who died in the flood was Joseph F. Rigge, a former president of Marquette University.

Planning for Flood Control

The people of Dayton were determined to stop another flood like this from happening. John H. Patterson led the idea for a managed river area. On March 27, 1913, Governor Cox appointed people to the Dayton Citizens Relief Commission. In May, this group raised over $2 million to pay for flood control efforts. They hired water engineer Arthur Ernest Morgan and his company from Tennessee. Morgan was asked to design a big plan using levees and dams to protect Dayton from future floods.

Morgan later worked on flood projects in Pueblo, Colorado, and for the Tennessee Valley Authority.

Morgan hired almost 50 engineers to study the Miami Valley river system and rain patterns. They also looked at flood data from Europe to understand general flood patterns. Based on their studies, Morgan showed eight different flood control plans to Dayton officials in October 1913. The city chose a plan similar to the flood control system in the Loire Valley in France.

This plan included five earthen dams and changes to the river channel through Dayton. The dams would have special openings to let out a controlled amount of water. The river channel would be made wider with stronger levees. Areas behind the dams would store floodwater and could be used as farmland between floods. Morgan's goal was to create a flood plan that could handle 140 percent of the water from the 1913 flood. Their study also figured out the river's boundaries for very rare, 1,000-year floods. Any businesses in those areas were to be moved.

With Governor Cox's support, Dayton lawyer John McMahon helped write the Vonderheide Act in 1914. This Ohio law allowed local governments to create conservancy districts for flood control. Some parts of the law were debated. For example, it gave local governments the right to raise money for these projects through taxes. It also allowed them to buy or take land needed for dams, basins, and flood plains, even if landowners didn't want to sell.

On March 17, 1914, the governor signed the Ohio Conservancy Act. This law allowed for the creation of conservancy districts with the power to build flood control projects. This Act became a model for other states like Indiana, New Mexico, and Colorado. Ohio's Upper Scioto Conservancy District was the first to form in February 1915. The Miami Conservancy District, which includes Dayton, was the second, formed in June 1915.

Morgan became the Miami Conservancy District's first chief engineer. The law was challenged in court, but the U.S. Supreme Court eventually said the law was legal. Legal battles continued from 1915 to 1919.

Miami Conservancy District's Flood Project

The Miami Conservancy District started building its flood control system in 1918. The project was finished in 1922 and cost over $32 million. Since then, it has stopped Dayton from having any flood as bad as the one in 1913. The Miami Conservancy District has protected the Dayton area from flooding more than 1,500 times. The cost of keeping the district running comes from property taxes collected every year from landowners in the district. Properties closer to the river and its natural flood plain pay more than those farther away.

Osborn, Ohio: A Town on the Move

The small village of Osborn, Ohio, wasn't badly damaged by the flood itself. However, it was affected by the flood's aftermath. The village was located in an area chosen to become part of the Huffman flood plain. Major train tracks from the Erie Railroad, the New York Central Railroad, and the Ohio Electric Railway all ran through Osborn. Because of the new flood control area, these train lines had to be moved several miles south, out of the flood plain, to run through Fairfield, Ohio.

The people of Osborn decided to move their homes instead of leaving them behind. Nearly 400 homes were moved three miles (5 km) to new foundations along Hebble Creek, next to Fairfield. Years later, the two towns merged to create Fairborn, Ohio. The name "Fairborn" was chosen to show that the two villages had joined together.

Other Impacts of the Flood

Orville and Wilbur Wright, who lived in Dayton, had made their first flight ten years before the flood. They were developing aviation in their workshop and near Huffman Prairie, which was close to where the Huffman Dam was planned. They had carefully recorded their flight experiments using a camera and had a large collection of photographic plates (like old-fashioned negatives). The flood caused water damage in their workshop. This created cracks and marks on these photographic plates. Pictures made from the plates before the flood were better quality than those made after. However, they had made few prints from these glass negatives before 1913 because the Wrights kept their pioneering work a secret. The images lost to flood damage were irreplaceable.

By 1913, the Miami and Erie Canal was still there, but hardly used. To help with the flooding, local leaders used dynamite to remove locks in the canal. This allowed the water to flow freely. Sections of the canal were also flooded and destroyed by the nearby river. Since the canals were no longer important for trade, Ohio's canals were mostly abandoned. Only small parts that supplied water to factories remained.

| Emma Amos |

| Edward Mitchell Bannister |

| Larry D. Alexander |

| Ernie Barnes |