History of Lutheranism facts for kids

Lutheranism is a Christian movement that started in the early 1500s. It began in the Holy Roman Empire (a large area in central Europe) when Martin Luther, a professor, wanted to fix problems he saw in the Catholic Church. He called for a public discussion about these issues.

Lutheranism quickly grew into a big religious and political movement. This was partly because important leaders supported it and because the printing press helped spread ideas fast. The movement spread across northern Europe and was a main part of the larger Protestant Reformation. Today, Lutheranism is practiced all over the world.

Contents

Europe Before the Reformation

The 1400s brought many changes to Europe. These changes helped create the right conditions for the Lutheran movement to grow. Before Martin Luther, other religious groups like the Hussites and Waldensians had similar ideas.

The Renaissance also played a big part. It was a time when people started to think differently and question things. Thinkers like Desiderius Erasmus began to ask questions about the role of the Church itself.

Society Changes in Europe

At the start of the 1500s, Europe had changed a lot. The terrible Black Death in earlier centuries had caused many people to die. This created new chances for people in lower classes to earn money and move up in society.

New inventions also helped with labor shortages and made work more productive. This led to new groups of people who worked in manufacturing and trade. Martin Luther's father, Hans Luther, was part of this new middle class. He made money by running copper mines. His family earned enough that Hans could plan for Martin to go to university and become a lawyer.

The Roman Catholic Church also faced challenges in the 1400s. There were disagreements about who should be pope, and the growing Ottoman Empire brought new pressures.

Books and Learning Spread

The spread of books and education greatly impacted the reformers. The Gutenberg Bible was first printed in 1455. Soon, Bibles and other books became much easier to find.

Universities also became important centers for new ideas, often outside the direct control of the Roman Catholic Church. In 1502, Frederick III, Elector of Saxony, started the University of Wittenberg. This is where Martin Luther, an Augustinian friar, became a "Professor of Bible."

Reformation Begins

In 1516 and 1517, a friar named Johann Tetzel was sent to Germany by the Roman Catholic Church. His job was to sell indulgences to raise money to rebuild St Peter's Basilica in Rome. Indulgences were like certificates that people bought to reduce the punishment for their sins.

On October 31, 1517, Luther wrote to Archbishop Albrecht of Mainz. He protested the sale of indulgences and included a copy of his "Disputation on the Power and Efficacy of Indulgences." This paper became famous as the Ninety-five Theses.

Luther did not plan to challenge the Church at first. He saw his paper as a scholarly discussion about Church practices. But some of his points were very challenging. For example, Thesis 86 asked: "Why does the pope, who is richer than the richest person, build St. Peter's Basilica with money from poor believers instead of his own?"

Luther strongly disagreed with a saying linked to Tetzel: "As soon as the coin in the coffer rings, the soul from purgatory springs." Luther believed that only God could forgive sins. He said that people who claimed indulgences could forgive all punishments and grant salvation were wrong. He taught that Christians should not stop following Christ because of such false promises.

According to Philipp Melanchthon, Luther nailed a copy of the Ninety-five Theses to the door of the Castle Church in Wittenberg on that same day. Church doors were like public bulletin boards back then. This event is now seen as the start of the Protestant Reformation. It is celebrated every year on October 31 as Reformation Day.

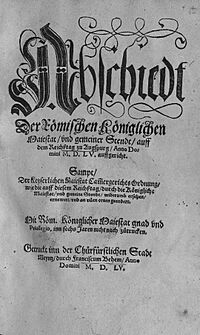

The Ninety-five Theses were quickly translated from Latin into German. They were printed and copied widely, making this one of the first big arguments helped by the printing press. Within two weeks, the ideas spread across Germany. Within two months, they were known throughout Europe.

Justification by Faith

From 1510 to 1520, Luther taught about parts of the Bible like the Psalms and the letters to the Romans and Galatians. As he studied, he began to see words like penance and righteousness in new ways.

He became sure that the Church had lost sight of what he believed were key Christian truths. The most important truth for Luther was the idea of justification. This is God's act of declaring a sinner righteous. Luther believed this happened only through faith and God's grace.

He started teaching that salvation is a gift from God's grace. It can only be received through faith in Jesus as the messiah. Luther wrote that this idea of justification is the most important part of Christian teaching.

Luther understood justification as completely God's work. He disagreed with the teaching that believers' good actions were done in cooperation with God. Luther wrote that Christians receive righteousness entirely from outside themselves. This righteousness is not just from Christ, but it is the righteousness of Christ. It is given to Christians through faith.

He wrote: "That is why faith alone makes someone just and fulfills the law." For Luther, faith was a gift from God. He explained his idea of "justification" in the Smalcald Articles:

The first and main point is this: Jesus Christ, our God and Lord, died for our sins and was raised again so we could be made right with God (Romans 3:24–25). He alone is the Lamb of God who takes away the sins of the world (John 1:29). God put all our wrongdoing on Him (Isaiah 53:6). Everyone has sinned, and they are made right freely, without their own works or merits, by God's grace, through the rescue that is in Christ Jesus, by His blood (Romans 3:23–25). This is necessary to believe. This cannot be gained or understood by any work, law, or merit. Therefore, it is clear and certain that this faith alone makes us right with God... Nothing of this point can be given up or surrendered, even if heaven and earth and everything else falls (Mark 13:31).

Luther's Exile

Diet of Worms

The order to stop Luther's teachings was given to the government leaders. On April 18, 1521, Luther appeared before the Diet of Worms. This was a big meeting of leaders from the Holy Roman Empire in the town of Worms. Emperor Charles V led the meeting. Prince Frederick III, Elector of Saxony, made sure Luther was promised safe travel to and from the meeting.

Johann Eck, speaking for the Empire, showed Luther copies of his writings. He asked Luther if the books were his and if he still believed what they said. Luther confirmed he wrote them but asked for time to think about the second question. After praying and talking with friends, he gave his answer the next day: "Unless I am convinced by the Bible or by clear reason... I cannot and will not take back anything, because it is not safe or right to act against one's conscience." He is also famously said to have added: "Here I stand. I can do no other. God help me. Amen."

For the next five days, private meetings were held to decide Luther's future. On May 25, 1521, the Emperor issued the Edict of Worms. It declared Luther an outlaw, banned his writings, and ordered his arrest. It said: "We want him to be caught and punished as a well-known heretic." It also made it a crime for anyone in Germany to give Luther food or shelter. It even allowed anyone to kill Luther without legal punishment. This Edict caused disagreements and worried more moderate people like Desiderius Erasmus.

At Wartburg Castle

Luther's disappearance during his trip home was planned. Frederick III, Elector of Saxony arranged for masked horsemen to secretly stop him. They took him to the safe Wartburg Castle in Eisenach. There, Luther grew a beard and lived secretly for almost a year, pretending to be a knight named Junker Jörg.

During his time at Wartburg (May 1521–March 1522), Luther translated the New Testament from Greek into German. He also wrote many important papers. He continued to attack Archbishop Albrecht of Mainz, which shamed the Archbishop into stopping the sale of indulgences in his areas.

Luther also wrote about his idea of justification to a philosopher named Jacobus Latomus. In a letter, he wrote: "Let your sins be strong, but let your trust in Christ be stronger... We will commit sins while we are here, for this life is not a place where justice resides."

In the summer of 1521, Luther wrote On the Abrogation of the Private Mass. In this, he criticized not just indulgences but also core Church practices. His essay Concerning Confession rejected the Roman Catholic Church's requirement of confession. However, he still believed private confession and absolution were valuable.

His New Testament translation was published in September 1522. It sold 5,000 copies in two months. In it, he explained that good actions come from faith; they do not create faith.

In Wittenberg, another reformer named Andreas Karlstadt started making changes that went further than Luther had planned. This caused problems, including Augustinian friars rebelling and statues in churches being destroyed. After secretly visiting Wittenberg in December 1521, Luther wrote a warning against rebellion. But Wittenberg became even more unstable when a group of radical thinkers, called the Zwickau prophets, arrived. They preached about equality, adult baptism, and Christ's quick return. Luther decided it was time to act.

Luther Returns to Wittenberg

Around Christmas 1521, some Anabaptists from Zwickau came to Wittenberg and caused a lot of trouble. Luther strongly disagreed with their extreme ideas and worried about the results. So, he secretly returned to Wittenberg on March 6, 1522. He wrote to the Elector: "During my absence, Satan has entered my sheepfold, and caused damage that I cannot fix by writing, but only by being here in person."

For eight days in Lent, starting on March 9, Luther preached eight sermons. These became known as the "Invocavit Sermons." In these sermons, he stressed the importance of key Christian values like love, patience, kindness, and freedom. He told the people to trust God's word instead of using violence to bring about change.

Do you know what the Devil thinks when he sees men use violence to spread the gospel? He sits with folded arms behind the fire of hell, and says with evil looks and a scary grin: "Ah, how smart these crazy people are to play my game! Let them continue; I will benefit. I love it." But when he sees the Word running and fighting alone on the battlefield, then he shudders and shakes with fear.

In 1534, Michael the Deacon from the Ethiopian Orthodox Church traveled to Wittenberg to meet with Martin Luther. They both agreed that the Lutheran Mass and the service used by the Ethiopian Orthodox Church were similar. Michael the Deacon also said that Luther's Christian beliefs were a "good creed." Luther saw that the Ethiopian Orthodox Church had practices like "communion in both kinds, Bibles in the local language, and married clergy." These practices became common in Lutheran Churches. For Lutherans, the Ethiopian Church showed that Luther's new Protestant idea of a church outside the Pope's power was valid, as it was "an ancient church with direct ties to the apostles."

Political and Religious Conflict

What began as a religious discussion became a social and political conflict. It put Luther and his German supporters against Emperor Charles V, France, the Pope, and their allies. This conflict would later lead to religious wars after Luther's death.

After meetings in Nuremberg failed to arrest Luther, a decision was made in 1526 at the First Diet of Speyer. It said that until a General Council could meet to settle Luther's ideas, the Edict of Worms would not be enforced. Each prince could decide if Lutheran teachings were allowed in his lands.

In 1529, at the Second Diet of Speyer, this decision was changed. This was despite strong protests from the Lutheran princes, free cities, and some Zwinglian areas. These states quickly became known as Protestants. At first, "Protestant" was a political term for states that resisted the Edict of Worms. Over time, it came to mean religious movements that opposed the Roman Catholic Church in the 1500s.

Lutheranism became known as a separate movement after the 1530 Diet of Augsburg. Emperor Charles V called this meeting to try to stop the growing Protestant movement. At the Diet, Philipp Melanchthon presented a written summary of Lutheran beliefs called the Augsburg Confession. Many German princes signed this document to define "Lutheran" territories. The Roman Catholic Church responded with the Confutatio Augustana at the same Diet.

In response to the Confutatio, Philipp Melanchthon wrote the Prima delineatio. Although the Emperor rejected it, Melanchthon improved it. It was later signed as the 1537 Apology of the Augsburg Confession.

Several Lutheran states, led by Elector John Frederick I of Saxony and Landgrave Philip I of Hesse, formed the Schmalkaldic League in 1531. At first, the Nuremberg Religious Peace of 1532 gave religious freedom to members of this League. During this time, Martin Luther used his influence to prevent war.

Martin Luther and the Reformation also brought big changes to church architecture and design. Protestant ideas said that the sermon, or spoken word, should be the main part of the church service. This meant the pulpit became the most important spot in the church. Churches were designed so everyone could hear and see the minister. The focus was on preaching God's Word.

Holy Communion tables were made of wood to show that Christ's sacrifice happened once for all. They were also placed closer to the people to show that people could directly reach God through Christ. So, Catholic churches were redecorated when they became reformed. Paintings and statues of saints were removed. Sometimes the altar table was placed in front of the pulpit, like at Strasbourg Cathedral in 1524. The pews were turned towards the pulpit. The first newly built Protestant church was the chapel of Neuburg Castle in 1543. The next was the chapel of Hartenfels Castle in Torgau, dedicated by Martin Luther on October 5, 1544.

Luther died in 1546. In 1547, the Schmalkaldic War began. It started as a fight between two Lutheran rulers. But soon, forces from the Holy Roman Empire joined. They defeated the Schmalkaldic League members, forcing many Lutherans to leave their homes. This continued until religious freedom for Lutherans was secured through the Peace of Passau in 1552 and the Peace of Augsburg in 1555.

Concordia: Doctrinal Harmony

The Lutheran movement was not defeated. In 1577, the next generation of Lutheran thinkers gathered the work of the earlier generation. They defined the beliefs of the Lutheran church in a document called the Formula of Concord. In 1580, this document was published with other important Lutheran texts. These included the Augsburg Confession, the Apology of the Augsburg Confession, Luther's Large and Small Catechisms, the Smalcald Articles, and the Treatise on the Power and Primacy of the Pope.

Together, these documents were put into a book called The Book of Concord. This book helped unite all German Lutherans with the same beliefs. It started the period of Lutheran Orthodoxy. The Lutheran Church sees itself as the "main trunk of the historical Christian Tree" founded by Christ and the Apostles. It believes that during the Reformation, the Church of Rome changed too much. The Augsburg Confession teaches that the faith confessed by Luther and his followers is not new. It is the true Christian faith, and their churches represent the true universal church. When Lutherans presented the Augsburg Confession to Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor, they explained that each belief was true to the Bible and also to the teachings of early Church leaders.

Early Orthodoxy: 1580–1600

The Book of Concord brought unity to Lutheranism. This was important because there had been many disagreements, especially between different groups of Lutherans. Lutheran beliefs became more clearly defined.

High Orthodoxy: 1600–1685

Lutheran scholasticism developed to help Lutherans argue with other groups, especially the Jesuits. Important Lutheran thinkers during this time included Johann Gerhard and Abraham Calovius.

Late Orthodoxy (1685–1730)

The 1600s were harder times than the early Reformation. This was partly due to the Thirty Years' War. Finland, for example, suffered a terrible famine in 1696–1697, and almost a third of its people died. This struggle to survive can be seen in the hymns and writings from that time.

Late Orthodoxy faced challenges from rationalism (philosophy based on reason) and Pietism. Pietism was a movement that wanted to focus more on personal faith, feelings, and studying the Bible. After a century of strong beliefs, Pietist thinkers like Philipp Jakob Spener warned that Lutheran orthodoxy was becoming too focused on ideas and not enough on changing lives. Pietism grew, but its focus on personal morality sometimes came at the cost of teaching about justification.

Rationalism and Revivals

Rationalism

During this time, rationalist philosophers from France, England, and Germany had a huge impact. Instead of faith in God and trust in the Bible, people were taught to trust their own reason and senses. At most, rationalism left people with a belief in a vague idea of God. Morality and church attendance dropped.

True faith was mostly found in small Pietist groups. However, some ordinary people kept Lutheran beliefs alive by using old catechisms, hymnbooks, and devotional writings. But overall, Lutheranism seemed to fade away because of rationalist philosophy.

Revivals

The Awakening

Napoleon's invasion of Germany promoted rationalism and angered German Lutherans. This sparked a desire among people to protect Luther's theology from the threat of rationalism. This Erweckung, or Awakening, argued that reason was not enough. It stressed the importance of emotional religious experience.

Small groups formed, often in universities, that focused on Bible study, reading religious writings, and revival meetings. Members of this movement eventually worked to bring back the traditional worship and beliefs of the Lutheran church in the Neo-Lutheran movement. A regular person, Luther scholar Johann Georg Hamann, became famous for fighting against rationalism and promoting the Awakening.

This Awakening also spread through Scandinavia. It was influenced by both German Neo-Lutheranism and Pietism. Danish pastor N. F. S. Grundtvig changed church life in Denmark through a reform movement starting in 1830. He also wrote many hymns. In Norway, Hans Nielsen Hauge, a lay preacher, emphasized spiritual discipline. In Sweden, Lars Levi Læstadius started a movement that focused on moral reform. In Finland, a farmer named Paavo Ruotsalainen started a reform movement by preaching about repentance and prayer.

Old Lutherans

In 1817, Frederick William III of Prussia ordered the Lutheran and Reformed churches in his territory to unite. This formed the Evangelical Church of the Prussian Union. This forced union of the two branches of German Protestantism caused a split called the Schism of the Old Lutherans.

Many Lutherans, called "Old Lutherans", chose to leave the official churches and form their own independent church groups, or "free churches." They did this despite being imprisoned or facing military force. Some even moved to the United States and Australia. A similar forced merger in Silesia led thousands to join the Old Lutheran movement.

Neo-Lutherans

Despite political interference in church life, local leaders tried to restore and renew Christianity. High school teacher August Friedrich Christian Vilmar turned from rationalism to faith. He realized the importance of the Augsburg Confession and other Lutheran beliefs. He was a supporter of the Neo-Lutheran movement, which worked to renew the church using the Lutheran Confessions.

Neo-Lutheran Johann Konrad Wilhelm Löhe and Old Lutheran leader Friedrich August Brünn sent young men overseas to serve as pastors to German Americans. The Inner Mission focused on renewing the situation at home. Johann Gottfried Herder, a church leader, joined the Romantic movement in his effort to protect human emotion and experience from rationalism.

Results

The Neo-Lutheran movement helped slow down the decline of religion and fight against atheistic Marxist socialism. It also partly continued the Pietist movement's efforts to fix social problems and focus on individual conversion.

However, the Neo-Lutheran call for renewal did not become widely popular in Europe. This was because its ideas were based on a grand, idealistic Romanticism that did not connect with a Europe that was becoming more industrialized and less religious. At best, the work of local leaders led to strong spiritual renewal in specific areas. But overall, people in Lutheran areas continued to become more distant from church life.

Starting in 1867, Lutherans who believed in traditional confessions and those with more liberal views joined to form the Common Evangelical Lutheran Conference. They worked against the constant threat of a forced union with the Reformed churches. However, they could not agree on how much agreement in beliefs was needed for church unity. Eventually, the fascist German Christians movement forced the final national merger of Lutherans and Reformed into a single Reich Church, the German Protestant Church, in 1933. After World War II, the German Protestant Church was re-founded with the new name Protestant Church in Germany.

See also

- High Church Lutheranism

- The Reformation and its influence on church architecture