History of Namibia facts for kids

The history of Namibia tells the story of this country from ancient times to its independence on 21 March 1990.

From 1884, Namibia was a German colony called German South West Africa. After the First World War, the League of Nations gave South Africa the job of looking after the territory. After World War II, the League of Nations ended. The new United Nations (UN) wanted to help former colonies become independent. South Africa disagreed, saying most people in the territory were happy with their rule.

This led to many legal arguments for twenty years. In October 1966, the UN General Assembly decided to end South Africa's right to control the territory. They declared that South West Africa would now be directly managed by the UN.

Contents

Ancient History of Namibia

Humans lived in the Huns Mountains in southern Namibia as early as 25,000 BC. Painted stone plates from that time show these early settlements. They are also some of the oldest artworks in the world. A piece of a human-like jaw, about thirteen million years old, was found in the Otavi Mountains. Stone Age weapons and tools also prove that early humans hunted wild animals in the region long ago.

The Brandberg Mountains have many rock paintings, mostly from around 2000 BC. We don't know for sure which groups made them. It's unclear if the San (also called Bushmen), who are one of Namibia's oldest groups along with the Damara, created these paintings.

The Nama people settled in southern Africa and southern Namibia around the first century BC. Unlike the San and Damara, the Nama raised their own livestock.

People of the North: The Ovambo and Kavango

The Ovambo and the smaller, related Kavango groups lived in northern Namibia. Some also lived in southern Angola and western Zambia. They were settled farmers who raised cattle and fished. They also made metal goods. Both groups were part of the Bantu nation. They rarely traveled south into central Namibia because the land there wasn't good for their farming lifestyle. However, they traded their knives and farm tools widely.

Bantu Migration: The Herero People

Around the 17th century, the Herero moved into Namibia. They were pastoral people, meaning they were nomadic and raised cattle. They came from the east African lakes and entered Namibia from the northwest. At first, they lived in Kaokoland. But in the mid-19th century, some tribes moved further south into Damaraland. Some tribes stayed in Kaokoland; these were the Himba people, who still live there today. During German rule, about one-third of the Herero population was killed in a terrible event called the Herero and Namaqua genocide. This event still causes anger today. An apology was sought more recently.

The Oorlams People

In the 19th century, white farmers, mostly Boers, moved further north. They pushed the native Khoisan peoples, who fought back strongly, across the Orange River. These Khoisan were known as Oorlams. They adopted Boer customs and spoke a language similar to Afrikaans.

The Oorlams had guns, which caused problems as more of them settled in Namaqualand. Soon, conflict started between them and the Nama. Led by Jonker Afrikaner, the Oorlams used their better weapons to take control of the best grazing land. In the 1830s, Jonker Afrikaner made a deal with the Nama chief Oaseb. The Oorlams would protect central Namibia's grasslands from the Herero, who were moving south. In return, Jonker Afrikaner was recognized as a leader. He received payments from the Nama and settled in what is now Windhoek, near Herero land.

The Afrikaners soon clashed with the Herero. Both groups wanted to use the grasslands of Damaraland for their cattle. This led to wars between the Herero and the Oorlams, and also between both of them and the Damara, who were the original people of the area. The Damara were forced out by the fighting, and many were killed. With their horses and guns, the Afrikaners were stronger in battle and forced the Herero to give them cattle as payment.

Baster Immigration

The last group of people now considered native to arrive in Namibia were the Basters. They were descendants of Boer men and African women (mostly Khoisan). They followed the Calvinist religion and spoke Afrikaans. They saw themselves as more "white" than "black" in their culture. Like the Oorlams, they were pushed north by white settlers. In 1868, about 90 families crossed the Orange River into Namibia.

The Basters settled in central Namibia and founded the city of Rehoboth. In 1872, they created the "Free Republic of Rehoboth." They adopted a constitution that said the nation should be led by a "Kaptein" (captain) chosen by the people. There would also be a small parliament, or Volkraad, with three elected citizens.

European Influence and Colonization

The first European to reach Namibia was the Portuguese explorer Diogo Cão in 1485. He briefly stopped on the Skeleton Coast and put up a limestone cross during his journey along Africa's west coast. The next European visitor was also Portuguese, Bartholomeu Dias. He stopped at what are now Walvis Bay and Lüderitz (which he called Angra Pequena) on his way around the Cape of Good Hope. The harsh Namib Desert was a huge barrier, so neither explorer went far inland.

For the next few centuries, the area was generally known as Cafreria ("the land of the kaffirs").

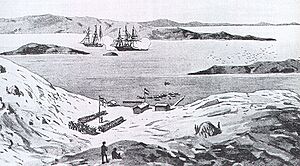

In 1793, the Dutch in the Cape decided to take control of Walvis Bay. It was the only good deep-water harbor along the Skeleton Coast. When the United Kingdom took control of the Cape Colony in 1805, they also took over Walvis Bay. But few colonists settled in the area, and neither the Dutch nor the British went far into the country.

One of the first European groups interested in Namibia were the missionaries. In 1805, the London Missionary Society began working in Namibia, moving north from the Cape Colony. In 1811, they founded the town of Bethanie in southern Namibia. They built a church there, which was long thought to be Namibia's oldest building. However, the site at ǁKhauxaǃnas, which existed before Europeans arrived, was later recognized as older.

In the 1840s, the German Rhenish Mission Society started working in Namibia and cooperated with the London Missionary Society.

It wasn't until the 19th century that European powers became truly interested in Namibia. This was during the "Scramble for Africa," when European countries tried to divide the African continent among themselves. Germany was a main player in this.

Britain made the first claim on a part of Namibia. They occupied Walvis Bay in 1797 and allowed the Cape Colony to add it in 1878. This was an attempt to stop Germany from taking over the area. It also made sure Britain controlled the good deep-water harbor on the way to their other colonies in East Africa.

In 1883, a German trader named Adolf Lüderitz bought Angra Pequena from the Nama chief Josef Frederiks II. He paid 10,000 German marks and 260 guns. He soon renamed the coastal area after himself, calling it Lüderitz. Lüderitz believed Britain would soon claim the whole area. So, he advised the German chancellor Otto von Bismarck to claim it first. In 1884, Bismarck did so, making German South West Africa a German colony.

The Caprivi Strip became part of German South West Africa after the Heligoland-Zanzibar Treaty on 1 July 1890. This treaty was between the United Kingdom and Germany. The Caprivi Strip gave Germany access to the Zambezi River, which connected to German colonies in East Africa. In exchange, Britain gained control of the island of Zanzibar in East Africa, while Germany got the island of Heligoland in the North Sea.

German South West Africa

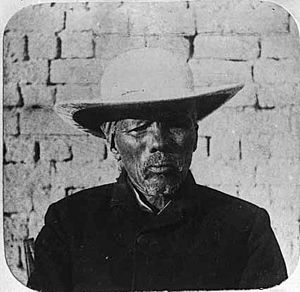

Soon after declaring Lüderitz and a large area along the Atlantic coast a German protectorate, German troops were sent in. Conflicts with the native tribes began, especially with the Namaqua. Led by chief Hendrik Witbooi, the Namaqua strongly resisted the German rule. Newspapers at the time called this conflict "The Hottentot Uprising."

However, the Namaqua's resistance was not successful. In 1894, Witbooi was forced to sign a "protection treaty" with the Germans. The treaty allowed the Namaqua to keep their weapons. Witbooi was released after promising not to continue the uprising.

In 1894, Major Theodor Leutwein became governor of German South West Africa. He tried to rule without much bloodshed, but he didn't fully succeed. The protection treaty did make things more stable, but small rebellions continued. An elite German regiment called the Schutztruppe put these down. Real peace was never achieved between the colonists and the native people.

A fence called the Red Line was built to stop animal diseases. It separated the north from the rest of the territory. This led to different rules: direct German control south of the line and indirect control north of it. This caused different economic and political situations for groups like the northern Ovambo people compared to the more central Herero people.

Namibia was the only German colony in Africa thought to be good for white settlement at the time. This attracted many German settlers. In 1903, there were 3,700 Germans living there. By 1910, this number grew to 13,000. Another reason for German settlement was the discovery of diamonds in 1908. Diamond mining is still a very important part of Namibia's economy today.

The government encouraged settlers to take land from the native people. Forced labor, which was very similar to slavery, was also used. As a result, relations between the German settlers and the native people got worse.

The Herero and Namaqua Wars

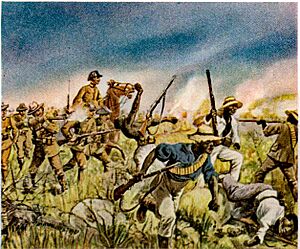

The small local rebellions grew into the terrible Herero and Namaqua Wars in 1904. The Herero attacked farms in the countryside, killing about 150 Germans.

The outbreak of the rebellion was seen as a result of Theodor Leutwein's softer approach. He was replaced by the harsher General Lothar von Trotha.

At the start of the war, the Herero, led by chief Samuel Maharero, had an advantage. They knew the land well and could easily defend themselves against the Schutztruppe (who only had 766 soldiers at first). Soon, the Namaqua people joined the war, again led by Hendrik Witbooi.

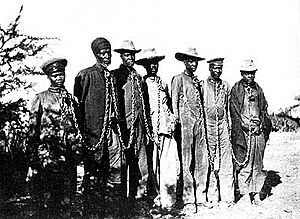

To handle the situation, Germany sent 14,000 more troops. They quickly crushed the rebellion in the Battle of Waterberg in 1904. Earlier, von Trotha had given an order to the Herero: leave the country or be killed. To escape, the Herero went into the dry Omaheke region, part of the Kalahari Desert. Many of them died of thirst there. The German forces guarded all water sources and were ordered to shoot any adult male Herero they saw. Later orders included killing all Herero and Nama, even children. Only a few managed to escape into nearby British lands.

These sad events are known as the Herero and Namaqua Genocide. Between 24,000 and 65,000 Herero people died (estimated to be 50% to 70% of their total population). About 10,000 Nama people also died (50% of their population). Many died from starvation or from drinking poisoned well water in the Namib Desert.

On 7 October 2007, descendants of Lothar von Trotha apologized to six chiefs of Herero royal families for their ancestor's actions.

South African Rule

In 1915, during World War I, South Africa launched a military campaign and took over the German colony of South West Africa.

In February 1917, Mandume Ya Ndemufayo, the last king of the Kwanyama people in Ovamboland, was killed. This happened in a joint attack by South African forces because he resisted South African rule over his people.

On 17 December 1920, South Africa began to manage South West Africa. This was under the rules of the League of Nations and a Class C Mandate agreement. A Class C mandate was for less developed territories. It gave South Africa full power to rule and make laws for the territory. However, it also required South Africa to improve the well-being and social progress of the people.

After the League of Nations was replaced by the United Nations in 1946, South Africa refused to give up its mandate. They did not want it replaced by a United Nations Trusteeship agreement, which would mean more international oversight. The South African government wanted to make South West Africa part of its own country. They never officially did, but they ruled it as if it were a "fifth province." The white minority in Namibia even had representatives in the whites-only Parliament of South Africa. In 1959, the colonial authorities in Windhoek tried to move black residents further away from the white part of town. The residents protested, and eleven protesters were killed in what became known as the Old Location Massacre. This event sparked a strong Namibian nationalist movement and led to black groups uniting against South African rule.

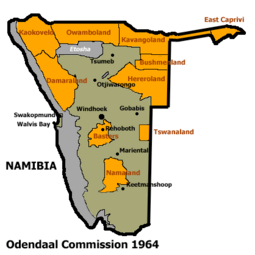

During the 1960s, many European colonies in Africa gained independence. Pressure grew on South Africa to do the same for Namibia (then South West Africa). In 1966, the International Court of Justice dismissed a complaint against South Africa's presence. After this, the U.N. General Assembly took away South Africa's mandate. Under growing international pressure to make its control of Namibia seem legal, South Africa set up the ‘Commission of Enquiry into South West Africa Affairs’ in 1962. This was also known as the Odendaal commission, named after Frans Hendrik Odendaal. Its goal was to bring South Africa's racist homeland politics to Namibia. At the same time, it tried to present the occupation as a modern and scientific way to help the people of Namibia.

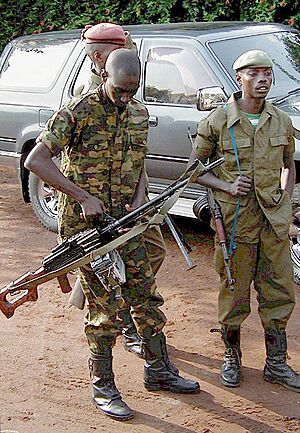

Namibian Struggle for Independence

In 1966, the South West Africa People's Organisation's (SWAPO) military group, the People's Liberation Army of Namibia (PLAN), began guerrilla attacks on South African forces. They entered Namibia from bases in Zambia. The first attack was the battle at Omugulugwombashe on 26 August. After Angola became independent in 1975, SWAPO set up bases in the southern part of that country. Fighting became more intense over the years, especially in Ovamboland.

In 1971, the International Court of Justice said that the UN had authority over Namibia. They ruled that South Africa's presence in Namibia was illegal and that South Africa had to leave immediately. The Court also advised UN member states not to support or recognize South Africa's presence.

In the summer of 1971-72, a general strike took place. About 25% of all contract workers (13,000 people) went on strike. It started in Windhoek and Walvis Bay and quickly spread to Tsumeb and other mines. The strike was against the contract system, which was very similar to slavery. It also supported Namibian independence.

In 1975, South Africa supported the Turnhalle Constitutional Conference. This conference aimed for an "internal settlement" for Namibia. SWAPO was not included. The conference mainly involved leaders from the bantustans and white Namibian political parties.

International Pressure

In 1977, the Western Contact Group (WCG) was formed. It included Canada, France, West Germany, the United Kingdom, and the United States. They worked together to find a way for Namibia to become independent in a way that everyone would accept. The WCG's efforts led to UN Security Council Resolution 435 in 1978, which aimed to solve the Namibian problem.

This settlement proposal was created after long talks with South Africa, the front-line states (Angola, Botswana, Mozambique, Tanzania, Zambia, and Zimbabwe), SWAPO, UN officials, and the Western Contact Group. It called for elections in Namibia under UN supervision. It also asked for all fighting to stop and for limits on the activities of South African and Namibian military and police.

South Africa agreed to help carry out Resolution 435. However, in December 1978, they held their own elections, ignoring the UN plan. SWAPO and some other political parties boycotted these elections. South Africa continued to rule Namibia through its own mixed-race governments and an appointed Administrator-General. After 1978, talks focused on how to supervise the elections needed for the settlement proposal.

Negotiations and Transition

During this time, four UN Commissioners for Namibia were appointed. South Africa refused to recognize any of them. However, discussions continued with UN Commissioner for Namibia N°2 Martti Ahtisaari. He played a key role in getting the Constitutional Principles agreed upon in 1982 by the front-line states, SWAPO, and the Western Contact Group. This agreement set the stage for Namibia's democratic constitution.

The US Government's role as a mediator was very important, though sometimes debated. For example, in 1984, they worked hard to get the South African Defence Force (SADF) to leave southern Angola. Some people who supported Namibia's independence saw the US policy as trying to stop Soviet-Cuban influence in Angola. Others thought it encouraged South Africa to delay independence.

From 1985 to 1989, a Transitional Government of National Unity, supported by South Africa and various ethnic political parties, tried to get recognition from the United Nations, but failed. Finally, in 1987, when Namibia's independence seemed more likely, the fourth UN Commissioner for Namibia Bernt Carlsson was appointed. When South Africa gave up control of Namibia, Commissioner Carlsson's job would be to manage the country, create its constitution, and organize fair elections for all people.

In May 1988, a US mediation team, led by Chester A. Crocker, brought negotiators from Angola, Cuba, and South Africa together in London. Observers from the Soviet Union were also there. For the next seven months, there was intense diplomatic work. The parties worked out agreements to bring peace to the region and make UN Security Council Resolution 435 (UNSCR 435) possible.

At the Ronald Reagan/Mikhail Gorbachev meeting in Moscow (May 29 – June 1, 1988), the US and Soviet leaders decided that Cuban troops would leave Angola. Soviet military aid would also stop once South Africa left Namibia. Agreements to make these decisions happen were signed in New York in December 1988. Cuba, South Africa, and Angola agreed to a full withdrawal of foreign troops from Angola. This agreement, called the Brazzaville Protocol, set up a Joint Monitoring Commission (JMC) with the United States and the Soviet Union as observers.

The Tripartite Accord, which included a bilateral agreement between Cuba and Angola, and a tripartite agreement between Angola, Cuba, and South Africa, was signed at UN headquarters in New York City on 22 December 1988. In this agreement, South Africa agreed to hand control of Namibia to the United Nations. (UN Commissioner N°4 Bernt Carlsson was not at the signing. He died on Pan Am Flight 103 which exploded over Lockerbie, Scotland on 21 December 1988, on his way from London to New York. South African foreign minister, Pik Botha, and a group of 22 officials were lucky. Their booking on Pan Am 103 was canceled at the last minute, and Pik Botha and a smaller group took an earlier flight.)

Within a month of the New York Accords being signed, South African president P. W. Botha had a mild stroke. This stopped him from attending a meeting with Namibian leaders on 20 January 1989. Acting president J. Christiaan Heunis took his place. Botha had fully recovered by 1 April 1989, when UNSCR 435 officially began. The South African-appointed Administrator-General, Louis Pienaar, started Namibia's journey to independence. Former UN Commissioner N°2, now UN Special Representative Martti Ahtisaari, arrived in Windhoek in April 1989 to lead the UN Transition Assistance Group's (UNTAG) mission.

The transition started with some difficulties. SWAPO President Sam Nujoma had promised the UN Secretary General in writing to follow a cease-fire and only bring unarmed Namibians back. However, it was claimed that about 2,000 armed members of PLAN, SWAPO's military wing, crossed the border from Angola. This seemed to be an attempt to set up a military presence in northern Namibia. UNTAG's Martti Ahtisaari got advice from Margaret Thatcher, who was visiting Southern Africa. He allowed a small number of South African troops to help the South West African Police restore order. A period of intense fighting followed, and 375 PLAN fighters were killed. At a quick meeting of the Joint Monitoring Commission in Mount Etjo, a game park near Otjiwarongo, it was agreed to keep the South African forces in their bases and send PLAN members back to Angola. While that problem was solved, small troubles continued in the north throughout the transition.

In October 1989, the UN Security Council ordered South Africa to demobilize about 1,600 members of Koevoet (Afrikaans for crowbar). The Koevoet issue was one of the hardest for UNTAG. This anti-rebel unit was formed by South Africa after UNSCR 435 was adopted, so it wasn't mentioned in the original settlement plan. The UN saw Koevoet as a military-like unit that should be disbanded. But the unit kept operating in the north in armored and heavily armed vehicles. In June 1989, the Special Representative told the Administrator-General that this was completely against the settlement proposal, which said the police should be lightly armed. Also, most Koevoet personnel were not suitable for continued work in the South West African Police (SWAPOL). So, the Security Council, in its resolution of 29 August, demanded that Koevoet be disbanded and its command structure removed. South African foreign minister, Pik Botha, announced on 28 September 1989 that 1,200 former Koevoet members would be demobilized the next day. Another 400 were demobilized on 30 October. UNTAG military monitors watched these demobilizations.

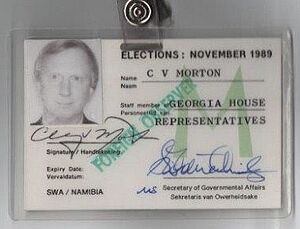

The 11-month transition period ended fairly smoothly. Political prisoners were given amnesty. Laws that discriminated against people were removed. South Africa pulled all its forces out of Namibia. About 42,000 refugees returned home safely and willingly with help from the Office of the UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). Almost 98% of registered voters came out to choose members for the Constituent Assembly. The elections were held in November 1989 and watched by foreign observers. The UN Special Representative certified them as free and fair. SWAPO won 57% of the votes. This was just short of the two-thirds needed to freely change the constitution. The opposition Democratic Turnhalle Alliance received 29% of the votes. The Constituent Assembly met for the first time on 21 November 1989. They all agreed to use the 1982 Constitutional Principles for Namibia's new constitution.

Independence

By 9 February 1990, the Constituent Assembly had written and approved a constitution. Independence Day was on 21 March 1990. Many international representatives attended, including the main figures: UN Secretary-General Javier Pérez de Cuéllar and President of South Africa F W de Klerk. They officially granted Namibia its independence together.

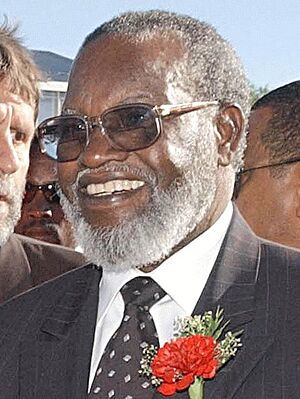

Sam Nujoma was sworn in as the first President of Namibia. Nelson Mandela (who had just been released from prison) and representatives from 147 countries, including 20 heads of state, watched.

On 1 March 1994, the coastal area of Walvis Bay and 12 islands offshore were given to Namibia by South Africa. This happened after three years of talks between the two governments. A temporary Joint Administrative Authority (JAA) had been set up in November 1992 to manage the 780 square kilometers of territory. The peaceful way this land dispute was solved was praised by the international community. It fulfilled the rules of UNSCR 432 (1978), which said Walvis Bay was a part of Namibia.

Independent Namibia

Since gaining independence, Namibia has successfully changed from white minority rule to a democratic society. Multiparty democracy has been introduced and kept, with local, regional, and national elections held regularly. Several political parties are active and have seats in the National Assembly. However, the SWAPO Party has won every election since independence. The change from President Sam Nujoma's 15-year rule to his successor, Hifikepunye Pohamba, in 2005 went smoothly.

The Namibian government has promoted a policy of national reconciliation. This means they offered forgiveness to those who fought on either side during the war for independence. The civil war in Angola had only a small impact on Namibians living in the north. In 1998, Namibia Defence Force (NDF) troops were sent to the Democratic Republic of the Congo as part of a Southern African Development Community (SADC) group. In August 1999, an attempt by a group in the northeastern Caprivi region to break away was stopped.

Re-election of Sam Nujoma

Sam Nujoma won the presidential elections of 1994 with 76.34% of the votes. There was only one other candidate, Mishake Muyongo of the DTA.

In 1998, with one year left until the next presidential election, Sam Nujoma would not have been allowed to run because he had already served the two terms the constitution allowed. So, SWAPO changed the constitution to allow three terms instead of two. They could do this because SWAPO had a two-thirds majority in both the National Assembly of Namibia and the National Council, which is the minimum needed to change the constitution.

Sam Nujoma was reelected as president in 1999. He won the election with 76.82% of the votes, and 62.1% of voters participated. Second was Ben Ulenga from the Congress of Democrats (COD), who won 10.49% of the votes.

Ben Ulenga was a former SWAPO member and a Deputy Minister of Environment and Tourism. He was also a High Commissioner to the United Kingdom. He left SWAPO and became one of the founding members of COD in 1998 after disagreeing with his party on several issues. He did not approve of the change to the constitution and criticized Namibia's involvement in Congo.

Nujoma was followed as President of Namibia by Hifikepunye Pohamba in 2005.

Land Reform

One of SWAPO's main policies, planned long before they came to power, was land reform. Because of Namibia's colonial and Apartheid past, about 20 percent of the population owned about 75 percent of all the land.

Land was supposed to be given mostly from the white minority to communities who had no land before and to former soldiers. The land reform has been slow. This is mainly because Namibia's constitution only allows land to be bought from farmers who are willing to sell. Also, the price of land is very high in Namibia, which makes it even harder. Squatting happens when people move to cities and live in informal settlements because they don't have proper housing.

President Sam Nujoma openly supported Zimbabwe and its president Robert Mugabe. During the land crisis in Zimbabwe, where the government took white farmers' land by force, there were fears among the white minority and Western countries that the same method would be used in Namibia.

Involvement in Conflicts in Angola and DRC

In 1999, Namibia signed a defense agreement with its northern neighbor Angola. This affected the Angolan Civil War that had been going on since Angola's independence in 1975. Both SWAPO and Angola's ruling party, MPLA, were leftist movements. SWAPO wanted to support the MPLA in Angola to fight the rebel group UNITA, whose main base was in southern Angola. The defense agreement allowed Angolan troops to use Namibian territory when attacking UNITA.

The Angolan civil war caused many Angolan refugees to come to Namibia. At its highest point in 2001, there were over 30,000 Angolan refugees in Namibia. The calmer situation in Angola has allowed many of them to return home with help from UNHCR. By 2004, only 12,600 remained in Namibia. Most of them live in the refugee camp Osire north of Windhoek.

Namibia also got involved in the Second Congo War. They sent troops to support the Democratic Republic of Congo's president Laurent-Désiré Kabila.

The Caprivi Conflict

The Caprivi conflict was an armed struggle between the Caprivi Liberation Army (CLA) and the Namibian government. The CLA was a rebel group that wanted the Caprivi Strip to become a separate country. The conflict started in 1994. It reached its peak in the early hours of 2 August 1999, when the CLA attacked Katima Mulilo, the main town of the Caprivi Region. Namibian government forces fought back and arrested many people believed to support the CLA. The Caprivi conflict led to the longest and largest trial in Namibia's history, known as the Caprivi treason trial.

After Sam Nujoma (2005-Present)

In March 2005, Namibia's first president, Sam Nujoma, stepped down after 15 years in power. He was followed by Hifikepunye Pohamba.

In December 2014, Prime Minister Hage Geingob, who was the candidate for the ruling SWAPO party, won the presidential elections. He received 87% of the votes. His predecessor, President Hifikepunye Pohamba, also from SWAPO, had served the maximum two terms allowed by the constitution. In December 2019, President Hage Geingob was re-elected for a second term, winning 56.3% of the votes.

On 4 February 2024, President Hage Geingob died. He was immediately succeeded by Vice-President Nangolo Mbumba as the new President of Namibia.

See also

In Spanish: Historia de Namibia para niños

In Spanish: Historia de Namibia para niños

- History of Africa

- History of Southern Africa

- Politics of Namibia

- List of presidents of Namibia

- Shark Island Concentration Camp

- Windhoek history and timeline