History of Newark, New Jersey facts for kids

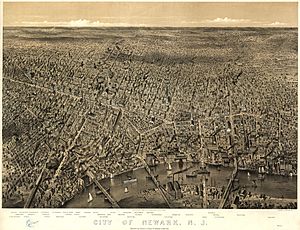

Newark has been the largest city in New Jersey for a long time. It was started in 1666 and grew a lot during the Industrial Revolution. It became a major center for business and culture in its area. Many people moved there in the mid-1900s, and its population was biggest in 1950. Later in the 1900s, the city faced tough times as people moved to the suburbs. But since the year 2000, Newark has seen new interest and investments. Its population has grown again in the 2010 and 2020 censuses.

Contents

How Newark Began in the 1600s

Newark was founded in 1666 by a group of Connecticut Puritans. They were led by Robert Treat and came from the New Haven Colony. They wanted to create a new settlement where their church rules would be strictly followed. This was because they didn't want to lose their power to others after Connecticut and New Haven joined together. Newark was the third settlement started in New Jersey.

The Puritans wanted to name the town "Milford" after their old home. But another settler, Abraham Pierson, suggested "Newark." He had been a preacher in Newark-on-Trent, England. He also said the community could be called "New Ark" like a "New Ark of the Covenant." The name was later shortened to Newark.

Robert Treat and his group bought the land along the Passaic River from the Hackensack Indians. They traded things like gunpowder, lead, axes, coats, guns, kettles, blankets, and even breeches for the land.

The first four settlers built their homes at what is now the intersection of Broad Street and Market Street. This spot is also known as "Four Corners." The Puritan Church had full control over the community until 1733. That year, a man named Josiah Ogden harvested wheat on a Sunday after a long rain. The Church punished him for working on the Sabbath. He left the church, and soon, other Christian missionaries arrived. They built a new church in 1746, which helped end the Puritan church's complete control. It took 70 years for Newark to fully remove all church-based rules, finally allowing non-Protestants to hold public office.

Newark's Growth During the Industrial Era

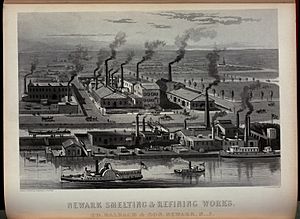

Newark started growing very fast in the early 1800s. A big reason for this was a man named Seth Boyden from Massachusetts. He arrived in Newark in 1815 and quickly made many improvements to how leather was made. He created a process for making patent leather. By 1870, Newark was making almost 90% of all the nation's leather. This brought in $8.6 million to the city that year. In 1824, Boyden also found a way to make iron that could be shaped easily.

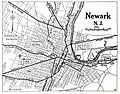

Newark also became more successful when the Morris Canal was built in 1831. This canal connected Newark to other parts of New Jersey, which were important for iron and farming. Railroads arrived in 1834 and 1835, making shipping even easier. Newark quickly became the main industrial center in the area. By 1826, Newark's population was 8,017, which was ten times bigger than in 1776.

In the mid-1800s, Newark's industries continued to grow and become more varied. The first successful plastic, called Celluloid, was made in a factory on Mechanic Street by John Wesley Hyatt. This Celluloid was used in carriages, billiard balls, and even dentures made in Newark. Dr. Edward Weston also improved a way to zinc electroplate things and created a better arc lamp in Newark. Newark's Military Park had the first public electric lights in the United States. Even Thomas Edison lived in Newark in the early 1870s before moving to Menlo Park. He invented the stock ticker there.

In the late 1800s, Newark's industries grew even more. Many Irish and German immigrants moved to the city. The Germans were often escaping problems in Europe in 1848. Like other groups, they started their own businesses, such as newspapers and breweries.

Newark also added insurance to its businesses in the mid-1800s. Mutual Benefit was founded in 1845, and Prudential was started in 1873. Prudential was founded by John Fairfield Dryden, who wanted to offer insurance to middle and lower-class families. By the late 1880s, companies in Newark sold more insurance than in any other city except Hartford, Connecticut.

Newark's population kept growing rapidly. In 1880, it was 136,500. By 1910, it had jumped to 347,000. People thought Newark's growth would never stop. In 1927, someone even said Newark might become "the greatest industrial center in the world."

However, there were also problems. Like many cities in the 1800s, Newark had poor sanitation. There was a lot of human and horse waste on the streets, and the sewage systems and water quality were not good.

Newark in the Early 1900s

Newark was a very busy place in the early to mid-1900s. Broad Street and Market Street were a major shopping area for the whole region. There were four big department stores: Hahne & Company, Bambergers and Company, S. Klein, and Kresge-Newark. Merchants proudly said that "Broad Street today is the Mecca of visitors."

In 1922, Newark had 63 live theaters and 46 movie theaters, with a lively nightlife. The intersection of Broad and Market Streets, known as the "Four Corners," was one of the busiest intersections in the United States. In 1915, over 280,000 people crossed it in just one day. By 1926, a check showed thousands of trolleys, buses, taxis, and cars passing through. Traffic was so heavy that the city turned the old Morris Canal bed into the Newark City Subway. This made Newark one of the few cities with an underground train system.

New skyscrapers were built every year, including the Art Deco National Newark Building and the Lefcourt-Newark Building. In 1948, right after World War II, Newark reached its highest population, almost 450,000 people. More immigrants from Southern and Eastern Europe also moved there. Newark had many distinct neighborhoods, including a large Jewish community.

Challenges After World War II

Even with all the industry, problems were growing. In 1930, a city official said that Newark was no longer a "quiet residential community." He noted that many important citizens had moved to the suburbs. While some thought Newark's decline started after World War II, others pointed to an earlier drop in the city's budget.

Some people believe Newark's problems grew because it built many large housing projects. Newark's housing had been a concern for a long time, as much of it was old. A 1944 study showed that 31% of homes in Newark were below healthy standards. Also, only 17% of homes were owned by the people living in them. Many parts of Newark had old wooden apartment buildings, and at least 5,000 homes were not good places to live. This led to calls for the government to help improve housing.

Historians like Kenneth T. Jackson suggested that cities like Newark, with a poor center and middle-class areas around it, did well when they could add these middle-class suburbs. When cities stopped being able to add suburbs, their problems got worse because the middle-class areas became separate from the poor center. In 1900, Newark's mayor hoped to add nearby towns like East Orange and Harrison. But only Vailsburg was ever added.

Many problems existed before World War II, but Newark faced more challenges afterward. The Federal Housing Administration made it hard to get mortgages or loans for homes in Newark, especially in certain areas. This was called redlining. Manufacturers also moved to places outside the city where wages were lower. They even got tax breaks for building new factories outside the city instead of fixing up old ones inside.

New highways like Interstate 280, the New Jersey Turnpike, and Interstate 78 were meant to improve transportation but actually hurt Newark. They cut through neighborhoods and forced many people to move. The highways also made it easier for middle-class workers to live in the suburbs and drive into the city for work.

Despite these issues, Newark tried to stay strong after the war. The city convinced Prudential and Mutual Benefit insurance companies to stay and build new offices. Rutgers University-Newark, New Jersey Institute of Technology, and Seton Hall University all grew their campuses in Newark. The Port Authority made Port Newark the first container port in the nation. They also took over Newark Liberty International Airport, which is now one of the busiest airports in the U.S.

The city also made mistakes with public housing and urban renewal. Newark's leaders thought it was great that the federal government would pay for 100% of housing projects. As industrial jobs decreased, more poor people needed housing. While other cities were careful about putting many poor families together, Newark eagerly took federal money. Eventually, Newark had more residents in public housing than any other American city.

The Italian-American First Ward neighborhood was hit hard by urban renewal. A 46-acre area with old, dense housing was torn down. In its place, multi-story, multi-racial high-rise buildings called Christopher Columbus Homes were built. This area used to have 8th Avenue, which was the main shopping street. These new buildings were never a good fit for the neighborhood. They were emptied in the 1980s and finally torn down in 1994.

From 1950 to 1960, Newark's total population dropped, but it gained 65,000 non-white residents. By 1966, black residents became the majority in Newark. This change happened faster than in most other northern cities. Many black people from the South and Puerto Ricans moved to Newark looking for industrial jobs. But these jobs were quickly disappearing. Many faced a big culture shock, moving from rural areas to a city where jobs were scarce. They left poverty in the South only to find poverty in the North.

In the 1950s, Newark's white population dropped by over 25%. By 1967, it had fallen even more. Even though the city's population changed, the racial makeup of city workers, especially the police, did not change as fast. In 1967, out of 1,400 police officers, only 150 were black. This difference caused racial tensions. Also, since black residents lived in neighborhoods that were white just two decades earlier, most of their apartments and stores were still owned by white people. As jobs were lost, incomes dropped, and many owners stopped maintaining buildings, leading to more decay.

Without asking the residents, Mayor Addonizio offered to tear down 150 acres of a crowded black neighborhood for the University of Medicine and Dentistry of New Jersey (UMDNJ). UMDNJ had originally wanted to build in a suburb.

The 1967 Newark Riots

On July 12, 1967, a taxi driver named John Smith was hurt while resisting arrest. A crowd gathered outside the police station where he was held. Because of a misunderstanding, the crowd thought Smith had died, but he had been taken to a hospital. This led to small fights between African Americans and police.

However, after TV news reported on it, bigger riots broke out on July 13. Twenty-six people died, 1,500 were hurt, and 1,600 were arrested. About $10 million worth of property was destroyed. More than a thousand businesses were burned or looted, and many never reopened. Newark's reputation was badly damaged. People started saying, "wherever American cities are going, Newark will get there first."

The reasons for the riots are explored in the documentary film Revolution '67.

Newark After the Riots

The 1970s and 1980s saw Newark continue to decline. Middle-class residents of all backgrounds kept leaving the city. Some areas became very poor and isolated. It was said that if New York media wanted to show urban despair, they would go to Newark.

In the 1997 novel American Pastoral by Newark-born author Philip Roth, a character says that Newark used to make everything. Now, he says, it's known for car theft, and instead of factories, there are liquor stores, pizza places, and churches, with everything else in ruins.

In January 1975, an article in Harper's Magazine looked at the fifty largest American cities. Newark was one of the five worst in 19 out of 24 categories and the very worst in nine. The article concluded that Newark was "the worst city of all" and "desperately needs help."

Despite these challenges, Newark has had some successes since the riots. In 1968, the New Community Corporation was founded. It became one of the most successful groups helping communities in the nation. By 1987, this group owned and managed 2,265 homes for low-income families.

Newark's downtown area began to be redeveloped in the decades after the riots. Less than two weeks after the riots, Prudential announced plans for a $24 million office complex near Penn Station, called "Gateway." Today, Gateway has thousands of office workers, though most don't live in Newark.

Before the riots, the University of Medicine and Dentistry of New Jersey was thinking about building in the suburbs. The riots and Newark's great need kept the medical school in the city. Instead of a huge 167-acre campus, the medical school was built on 60 acres. Students there started the "Student Family Health Clinic" to give free healthcare to people who needed it. This clinic still operates today.

In 1970, Kenneth A. Gibson was elected as Newark's first African-American mayor. He was also the first black mayor of a major city in the northeastern U.S. The 1970s were a time of disagreements between Gibson and the shrinking white population. Gibson admitted that Newark "may be the most decayed and financially crippled city in the nation." He and the city council raised taxes to try to improve services like schools and sanitation. However, these actions didn't help Newark's economy. The CEO of Ballantine's Brewery even said that Newark's $1 million annual tax bill caused the company to go out of business.

Newark's Renaissance: A New Beginning

Downtown Newark's Revival

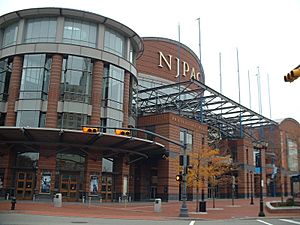

The New Jersey Performing Arts Center (NJPAC) opened downtown in 1997. It cost $180 million and was seen as the first step in the city's comeback. NJPAC brought people to Newark who might not have visited otherwise. It is known for its great sound quality and is home to the New Jersey Symphony Orchestra. NJPAC also hosts many famous artists and groups.

Since then, the city has built a baseball stadium (Riverfront Stadium) for the Newark Bears, the city's minor league team. In 2007, the Prudential Center, nicknamed "The Rock," opened for the New Jersey Devils hockey team. The Passaic River waterfront is being improved to give people access to the river. The Newark Public Library is also planning a big renovation. The Port Authority built a train connection to the airport (AirTrain Newark). Many new businesses have also opened downtown.

While much of the city's efforts have focused on downtown, nearby neighborhoods have also started to see some development, especially in the Central Ward. Since 2000, Newark's population has grown, which is the first increase since the 1940s. However, this "Renaissance" has not been felt equally across the city. Some areas still have lower incomes and higher rates of poverty.

By the mid-2000s, the crime rate had fallen by 58% from its highest points in the mid-1990s.

Newark's nicknames show its efforts to rebuild. In the 1950s, Mayor Leo Carlin called it New Newark to encourage businesses to stay. In the 1960s, it was called the Gateway City because of the redeveloped Gateway Center downtown. More recently, the media and public have called it the Renaissance City to recognize its efforts to come back to life.

Lincoln Park: An Eco-Village Vision

The Lincoln Park/Coast neighborhood is another area in Newark that is being redeveloped on a large scale. This area, once called The Coast, is now known as the Lincoln Park/Coast Cultural District. It is being planned as an "urban eco-village." Future plans include 300 green homes, townhomes, condos, and a Museum of African-American Music. The front of the South Park Presbyterian Church, which will be part of the museum, began being restored in 2008.

This area already has the Theater Cafe, the City Without Walls gallery, Brick City Urban Farms, and Symphony Hall, along with other cultural sites. Symphony Hall is likely to be renovated soon. The Lincoln Park Coast Cultural District (LPCCD) is the group leading this development. They also put on the Annual Lincoln Park Music Festival, which brings in thousands of visitors each year.

After much development downtown and the need to connect Newark Penn Station and Broad Street Station, the first part of the light rail was built. With the museum as a key point in the Coast area and the need for a second link to Newark Airport, this neighborhood is being considered for a future light rail system with a stop at Lincoln Park/Symphony Hall.

Images for kids

-

Mary Nimmo Moran, Newark, N.J., from the Passaic, 1879, National Gallery of Art

-

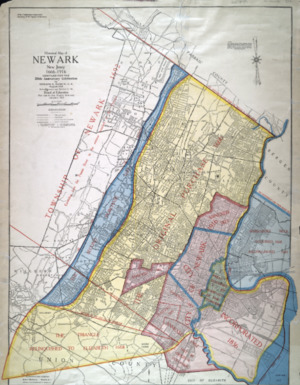

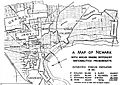

A map from around 1910 showing different ethnic groups in Newark, New Jersey

See also

In Spanish: Historia de Newark para niños

In Spanish: Historia de Newark para niños

| William M. Jackson |

| Juan E. Gilbert |

| Neil deGrasse Tyson |