History of crossbows facts for kids

The crossbow is a powerful weapon that looks a bit like a bow mounted on a stock, which is a bit like a gun's body. It shoots special arrows called bolts or quarrels. People think crossbows first appeared in China and Europe a very long time ago, between 700 and 500 BC.

In China, the crossbow was a super important military weapon from the Warring States period all the way to the end of the Han dynasty. Sometimes, as many as half the soldiers in an army were crossbowmen! After the Han dynasty, its popularity went down, maybe because heavy cavalry (soldiers on horseback) became more common. Even so, the crossbow was never completely forgotten. People were still suggesting it for armies in the 1600s, but by then, firearms like guns and traditional bows were taking over.

In the Western world, an early crossbow called the gastraphetes was described by a Greek scientist named Heron of Alexandria around 1 AD. He thought it was an early version of the catapult, meaning it existed before 400 BC. Besides the gastraphetes, there isn't much proof of crossbows in ancient Europe. Some old Roman carvings show what might be crossbows, but they seem to be for hunting, not fighting. It's not clear how much crossbows were used in ancient Europe or if they were even used in wars. Other ancient European arrow-shooting machines like the ballista were different because they used twisting power, not a bow. Crossbows aren't mentioned in European writings again until 947 AD, when they were used by the French during a siege. From the 1000s onwards, crossbows and crossbowmen became very important in medieval European armies, except for the English, who preferred their longbows. By the 1500s, gunpowder weapons like cannons and muskets replaced military crossbows in Europe. Hunters kept using them for another 150 years because they were quiet.

Some people think medieval European crossbows came from China, but there are some differences in how their trigger mechanisms worked.

Contents

Terminology

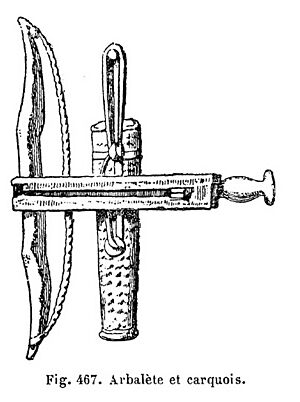

A person who uses or makes crossbows is sometimes called an arbalist or arbalest.

The words arrow, bolt, and quarrel all mean the projectiles shot from a crossbow.

The lath or prod is the bow part of the crossbow.

The stock is the wooden body where the bow is attached. It was also called the tiller in medieval times.

The lock is the part that releases the string, including the trigger lever and other pieces.

China

Early History

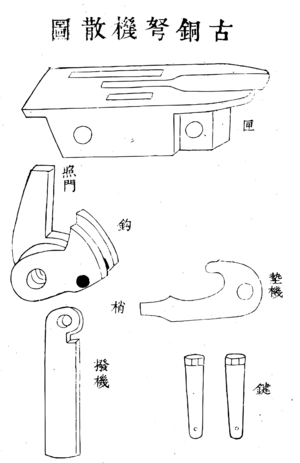

Archaeologists have found parts of crossbows made of bronze in China that date back to about 650 BC. These parts, especially the trigger mechanisms, have been found in ancient tombs. Some early crossbows might have even shot round pellets instead of arrows.

The oldest Chinese writings that mention crossbows are from the 300s or 400s BC. These texts talk about huge crossbows used during sieges. Even Sun Tzu's famous book, The Art of War, mentions crossbows and compares a drawn crossbow to 'might' or power.

Some states during the Warring States period had special armored crossbow units. These soldiers were known for being tough. For example, some could march over 160 kilometers (100 miles) without stopping! Others could march over 40 kilometers (25 miles) in a single day while wearing heavy armor and carrying a large crossbow with 50 bolts, a halberd, a helmet, a sword, and three days' worth of food. Soldiers who could do this were rewarded with tax breaks for their whole family.

Han Dynasty Use

The Huainanzi (an ancient text) warned against using crossbows in marshy areas because it was hard to load them there. The Records of the Grand Historian (finished in 94 BC) tells how Sun Bin defeated an enemy by ambushing them with crossbowmen at the Battle of Maling.

In the 100s AD, Chen Yin gave advice on how to shoot a crossbow:

When shooting, your body should be as steady as a board, and your head should be able to move easily like an egg. Your left foot should be forward, and your right foot should be straight. Your left hand should be like it's leaning on a branch, and your right hand like it's holding a child. Then hold the crossbow and aim at the enemy, hold your breath, and then breathe out as you shoot. This way, you will be calm. After focusing deeply, the arrow goes, and the bow stays. When your right hand moves the trigger, your left hand should not even know it. One body, but different parts doing different jobs, like a perfect match; this is the way to hold the crossbow and shoot accurately.

– Chen Yin

It's clear from old records found in China that the Han dynasty really liked crossbows. For example, in one set of records, bows are mentioned only twice, but crossbows are mentioned thirty times! Crossbows were made in large numbers in government factories. Their designs got better over time. A crossbow from 1068 AD could shoot through a tree from 140 paces away. Huge numbers of crossbows were used, sometimes as many as 50,000 in the Qin dynasty and hundreds of thousands during the Han. By the 100s BC, the crossbow had become the main weapon of the Han armies. Han soldiers had to be able to pull a crossbow with a draw-weight of 76 kilograms (168 pounds) to be a crossbowman.

| Item | Number | Government |

|---|---|---|

| Crossbow | 537,707 | 11,181 |

| Crossbow bolts | 11,458,424 | 34,265 |

| Bow | 77,521 | |

| Arrows | 1,199,316 | 511 |

Later Chinese History

After the Han dynasty, crossbows were not as popular, but they became more common again during the Tang dynasty. An ideal army of 20,000 soldiers would include 2,200 archers and 2,000 crossbowmen.

During the Song dynasty, the government tried to stop people from owning military crossbows. But even with bans, many people started using crossbows for hunting and fun. Rich young people even formed crossbow shooting clubs!

By the late Ming dynasty, crossbows were not produced much anymore. Firearms like cannons and muskets were being made instead.

Military crossbows were loaded by stepping on the bow with your feet and pulling the string with your arms and back. During the Song dynasty, stirrups were added to make it easier to load and to protect the bow. Larger crossbows were sometimes loaded while lying down, or with winches.

Crossbow Strengths and Weaknesses

For shooting through hard things and over long distances, and when defending mountain passes where there is much noise and strong attacks, nothing works like the crossbow. However, because it is slow to load, it is hard to deal with sudden attacks. A crossbow can only be shot three times by one person before needing hand-to-hand weapons. Some thought crossbows were not good for fighting, but the problem was not the crossbow itself, but commanders who did not know how to use them. All the military experts of the Tang dynasty said the crossbow had no advantage over hand-to-hand weapons. They wanted long spears and big shields in the front line to stop charges, and made crossbowmen carry swords and long-handled weapons. The result was that if the enemy attacked in open order with hand-to-hand weapons, the soldiers would throw away their crossbows and use those instead. So, a group from the back was sent to collect the crossbows.

– Zeng Gongliang

Crossbows allowed soldiers to shoot with more power and accuracy because they were more stable. But they were slower to reload than regular bows.

In 169 BC, Chao Cuo noted that crossbows could defeat the Xiongnu (nomadic warriors):

Of course, the Yi and Di (nomads) are skilled at mounted archery (using short bows), but the Chinese are good at using nu che (crossbow carriages). These carriages can form a defensive circle that cavalry cannot break through. Also, crossbows can shoot their bolts a long way and do more damage than short bows. And if the barbarians pick up the crossbow bolts, they cannot use them. Recently, the crossbow has unfortunately been neglected; we must think about this carefully... The strong crossbow and the javelin-shooting arcuballista have a long range; something the Huns' bows cannot match. Using sharp weapons with long and short handles by trained armored soldiers in different groups, including crossbowmen alternately advancing (to shoot) and retreating (to load); this is something the Huns cannot even face. The crossbow troops ride forward and shoot all their bolts in one direction; this is something the Huns' leather armor and wooden shields cannot stop. Then the horse-archers get off their horses and fight on foot with swords and spears; this is something the Huns do not know how to do.

– Chao Cuo

The Wujing Zongyao (a military encyclopedia) said that using many crossbows together was the best way to fight against northern cavalry charges. Even if the bolts missed, they were too short for the nomadic archers to use as their own arrows. Crossbows were also good for picking off important targets, like when a Song crossbowman shot the Liao Dynasty general Xiao Talin in 1004 AD.

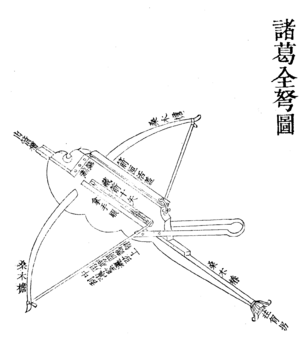

Repeating Crossbow

The Zhuge Nu is a handy little weapon that even a scholar or palace woman can use for self-defense... It shoots weakly, so you have to put poison on the darts. Once the darts have "tiger-killing poison," you can shoot it at a horse or a man, and as long as it draws blood, your enemy will die right away. The downside to the weapon is its very short range.

– Complete Classics Collection of Ancient China

The repeating crossbow, which could shoot multiple bolts quickly, was invented in China during the Warring States Period (around 400 BC). The earliest ones found had a pistol grip and were loaded by pulling a mechanism at the back. Later Ming dynasty repeating crossbows were loaded by pushing a lever back and forth. Handheld repeating crossbows were not very powerful and often needed poison on their darts to be deadly. However, much larger versions were mounted on stands during the Ming dynasty.

In 180 AD, Yang Xuan used a type of repeating crossbow that was powered by wheels. He loaded wagons with lime dust and put automatic crossbows on others. He used the wind to blind the enemy with dust, then sent the driverless wagons with burning rags on their horses' tails into the enemy lines. The crossbows, powered by the wheels, fired randomly, causing a lot of damage and confusion.

Even though the invention of the repeating crossbow is often credited to Zhuge Liang, he actually just improved existing multiple-bolt crossbows.

Repeating crossbows were used on ships during the Ming dynasty and continued to be used until the late Qing dynasty, when they couldn't compete with firearms anymore.

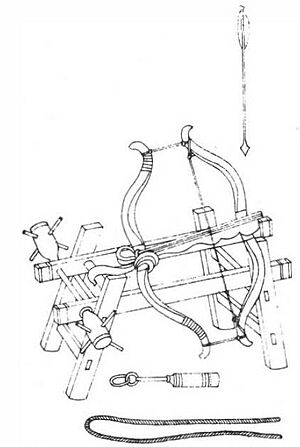

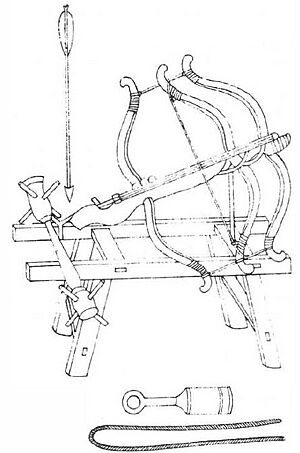

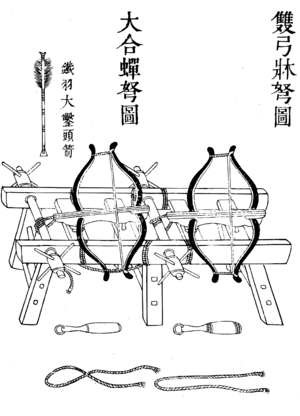

Mounted Crossbows

Large crossbows mounted on stands, called "bed crossbows," were used as early as the Warring States period. They were defensive weapons placed on city walls. By the Han dynasty, they were used as mobile artillery. Around the 400s AD, people started combining multiple bows to make them even more powerful, creating double and triple bow crossbows. Some Tang dynasty versions of these weapons could shoot over 1,000 meters (1,090 yards)! These huge weapons needed a lot of skill to build and operate. They were mainly used from the 700s to 1000s AD.

Multiple Bolt Crossbows

The multiple bolt crossbow, which could shoot several bolts at once, appeared around the late 300s BC. One text from 320 BC describes it mounted on a three-wheeled carriage on city walls. It was loaded using a foot pedal and shot 3-meter (10-foot) long arrows. Other ways to load them included winches or oxen. While this weapon could shoot many bolts, it was less accurate because the bolts further from the center of the string would fly off course. It had a maximum range of 450 meters (490 yards).

When Qin Shi Huang's magicians failed to contact spirits, they blamed large monsters blocking their way. Qin Shi Huang went out with a multiple bolt crossbow himself and, finding no monsters, killed a big fish.

In 99 BC, these weapons were used as field artillery against attacking cavalry.

Even though Zhuge Liang is often given credit for the repeating crossbow, this is a mistake. He actually improved a multiple bolt crossbow that could shoot ten iron bolts at once, each 20 centimeters (8 inches) long.

In 759 AD, Li Quan described a multiple bolt crossbow that could destroy city walls and towers. It was a very powerful crossbow mounted on wheels, loaded with a winch, and could shoot seven arrows at once. The middle arrow was the longest, and the others got smaller. It could hit anything within 700 paces, even strong structures.

By 1530 AD, this weapon was considered outdated.

| Weapon | Shots per minute | Range: meters (feet) |

|---|---|---|

| Chinese crossbow | 170–450 m (558–1,476 ft) | |

| Cavalry crossbow | 150–300 m (492–984 ft) | |

| Repeating crossbow | 28–48 | 73–180 m (240–591 ft) |

| Double shot repeating | 56–96 | 73–180 m (240–591 ft) |

| Weapon | Crew | Draw weight: kilograms (pounds) | Range: meters (feet) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mounted multi-bolt crossbow | 365–460 m (1,198–1,509 ft) | ||

| Mounted single-bow crossbow | 4–7 | 250–500 m (820–1,640 ft) | |

| Mounted double-bow crossbow | 10 | 350–520 m (1,148–1,706 ft) | |

| Mounted triple-bow crossbow | 20–100 | 950–1,200 kg (2,094–2,646 lb) | 460–1,060 m (1,509–3,478 ft) |

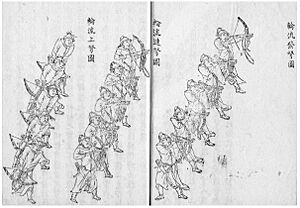

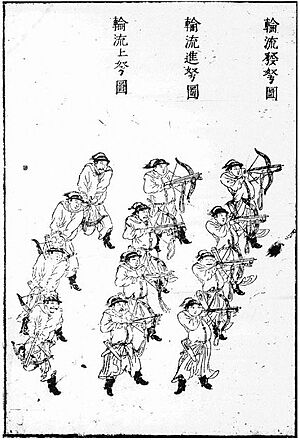

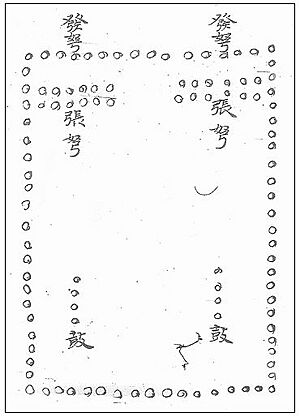

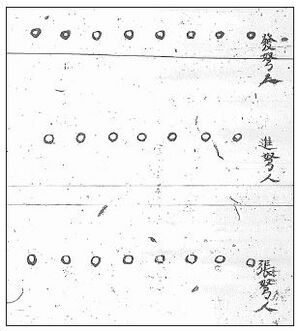

Volley Fire Tactics

The idea of continuous, organized shooting, called volley fire or countermarch, might have been used with crossbows as early as the Han dynasty. But clear pictures of it appeared during the Tang dynasty. A text from 759 AD shows a crossbow formation where some soldiers are shooting while others are reloading. The commander would use drums to tell them when to shoot and when to reload. This way, the crossbows would fire non-stop, making it hard for the enemy to get close.

Another text from 801 AD also describes this technique: "Crossbow units should be divided into teams that can focus their arrow shooting... Those in the center should load their bows while those on the outside should shoot. They take turns, moving around, so that once they've loaded, they move to the outside ranks, and once they've shot, they move back inside the formation. This way, the sound of the crossbow will not stop, and the enemy will not harm us."

The Wujing Zongyao (a Song dynasty military book) said that during the Tang period, crossbows weren't used as effectively as they could have been because soldiers were afraid of cavalry charges. The book suggested training soldiers to stand firm like a mountain and shoot continuously into the enemy, so that none would survive. The Song volley fire formation added an "advancing crossbows" line between the shooting and reloading lines. Both Tang and Song manuals stressed that arrows should be shot in a continuous stream, meaning no friendly troops should be in the way.

Regarding how to use the crossbow, it cannot be mixed with hand-to-hand weapons, and it is best when shot from high ground downwards. It only needs to be used so that the men inside the formation are loading while the men in the front line are shooting. As they come forward, they use shields to protect their sides. So, each in their turn, they draw their crossbows and come up; then as soon as they have shot bolts, they return again into the formation. Thus the sound of the crossbows is constant, and the enemy can hardly even run away. Therefore we have the following drill – shooting rank, advancing rank, loading rank.

– Zeng Gongliang

The Song dynasty used this volley fire technique very well during the Jin-Song Wars. In 1131 AD, a Song general named Wu Jie defeated a Jin commander by having his best archers and crossbowmen shoot in turns, like rain. The enemy fell back, and Wu Jie attacked with cavalry. The Jin troops were defeated, and their commander was hit by an arrow and barely escaped.

Southeast Asia

There's a theory that crossbows might have started independently in Southeast Asia, based on language studies. Crossbows are still used by some tribal groups there for hunting and war.

Around 300 BC, King An Dương of Âu Lạc (now northern Vietnam) had a man named Cao Lỗ build a special crossbow called the "Saintly Crossbow of the Supernaturally Luminous Golden Claw." It was said to be able to kill 300 men with one shot. Some historians think the crossbow and its name might have come to China from people in the south around 400 BC. However, crossbow parts found in China date back even earlier, to the 600s BC.

In 315 AD, a man named Nu Wen taught the Chams (people in Southeast Asia) how to build forts and use crossbows. The Chams even gave crossbows as gifts to the Chinese sometimes.

Siege crossbows were taught to the Chams by a Chinese man who was shipwrecked there in 1172 AD. He taught them how to use siege crossbows and ride horses while shooting. In 1177 AD, the Champa used crossbows when they attacked and sacked Angkor, the capital of the Khmer Empire. The Khmer also had double-bow crossbows mounted on elephants.

Europe

Ancient Europe

Greece

The earliest crossbow-like weapons in Europe probably appeared around the late 400s BC. This was the gastraphetes, an ancient Greek crossbow. It was described by Heron of Alexandria in his book about catapults. He said the gastraphetes was an early version of the catapult. It was called the "belly-bow" because the user would press it against their stomach to load it, which helped store more power than regular Greek bows. It was used in the Siege of Motya in 397 BC.

Other arrow-shooting machines like the larger ballista and smaller Scorpio also existed around 338 BC, but these were torsion machines (using twisting power) and are not considered true crossbows.

Rome

A Roman writer named Vegetius (late 300s AD) is the only person from that time who mentions ancient Roman crossbows. In his book De Re Militaris, he talks about arcubalistarii (crossbowmen) working with archers and artillery. However, it's debated whether these "arcuballistas" were actually crossbows or other torsion weapons. Vegetius said these weapons were well-known, so he didn't describe them in detail, which is frustrating for historians today!

There is almost nothing written about them except brief mentions by the military historian Vegetius (around 386 AD) of 'manuballistae' and 'arcuballistae,' which he said he didn't need to describe because they were so well known. His decision was very unfortunate, as no other writer of that time mentions them at all. Perhaps the best guess is that the crossbow was mainly known in late ancient Europe as a hunting weapon, and was only used locally in certain units of the armies of Theodosius I, which Vegetius happened to know about.

– Joseph Needham

The only pictures of Roman arcuballistas come from carvings in Roman Gaul (modern France) that show them in hunting scenes. These crossbows looked longer than later medieval ones, more like Greek and Chinese crossbows.

Medieval Europe

Crossbows are barely mentioned in Europe from the 400s AD until the 900s AD. However, there are pictures of crossbows used for hunting on four ancient stones from early medieval Scotland (6th to 9th centuries).

The crossbow reappeared in 947 AD as a French weapon during the siege of Senlis. They were used at the battle of Hastings in 1066 AD, and by the 1100s, they were common battlefield weapons. The oldest parts of a European crossbow found so far date to the 1000s AD.

Crossbows are not mentioned in Byzantine writings until the 1000s AD. Anna Komnene (1083–1153 AD), a Byzantine princess and historian, described the crossbow as a new weapon from Western European crusaders (whom she called barbarians) and said it was unknown to the Greeks:

This cross-bow is a barbarian bow quite unknown to the Greeks; and it is not stretched by the right hand pulling the string while the left pulls the bow in the other direction. Instead, the person stretching this warlike and very far-shooting weapon must lie, one might say, almost on their back and use both feet strongly against the bow's curve and pull the string with both hands with all their might in the opposite direction. In the middle of the string is a socket, a cylindrical cup fitted to the string itself, about as long as a good-sized arrow, reaching from the string to the very middle of the bow; and through this, many kinds of arrows are shot out. The arrows used with this bow are very short, but very thick, with a very heavy iron tip at the front. And when fired, the string shoots them out with enormous violence and force, and whatever these darts hit, they do not fall back, but they pierce through a shield, then cut through a heavy iron armor, and fly through and out the other side. So violent and unstoppable is the shot of these arrows. Such an arrow has been known to pierce a bronze statue, and if it hits the wall of a very large town, the arrow's point either sticks out on the inside or buries itself in the middle of the wall and is lost. Such then is this monster of a crossbow, and truly a devilish invention. And the poor person who is hit by it dies without feeling anything, not even the blow, no matter how strong it is.

– Anna Komnene

The first medieval European crossbows were made of wood, usually yew or olive wood. Crossbows with stronger composite (made of different materials) bows started appearing around the late 1100s, and crossbows with steel bows came out in the 1300s. These steel crossbows, sometimes called arbalests, were much more powerful and needed mechanical tools like the cranequin or windlass to load them. They could only shoot about two bolts per minute, compared to twelve or more for a skilled archer. This often meant crossbowmen needed a large shield called a pavise to protect them. Even with stronger bows, wooden ones remained popular into the 1400s because they were less affected by humidity and cold.

Crossbows replaced hand bows in many European armies during the 1100s, except in England, where the longbow was more popular. Crossbowmen were highly respected professional soldiers and often earned more money than other foot soldiers. The leader of the crossbowmen was one of the highest positions in many medieval armies. In Spain, crossbowmen were even given a status similar to knights.

However, the English longbowmen often defeated French forces using composite crossbows at battles like Crécy (1346 AD), Poitiers (1356 AD), and Agincourt (1415 AD). Because of this, the use of crossbows in France declined, and the French tried to train their own longbowmen. But after the Hundred Years' War, the French mostly stopped using longbows, and military crossbows became popular again. Crossbows continued to be used in French armies by both foot soldiers and mounted troops until about 1520 AD. Like elsewhere in Europe, the crossbow was largely replaced by the handgun. Spanish forces used crossbows a lot in the New World, even after they were less common in Europe. Crossbowmen were part of Hernán Cortés' conquest of the Aztec Empire and Francisco Pizarro's first trip to Peru.

Comparing Chinese and European Crossbows

The Chinese crossbow had a longer "power stroke" (how far the string moved when shot), about 51 centimeters (20 inches). Early medieval European crossbows usually had a much shorter power stroke, only about 10-18 centimeters (4-7 inches). This was possible because the Chinese trigger design was more compact, allowing it to be placed further back. Chinese crossbows also used relatively short composite bows that could be drawn back further without breaking. Chinese crossbows had draw-weights ranging from 68 to 340 kilograms (150 to 750 pounds).

...the Chinese used the crossbow much more widely as an infantry weapon than the Byzantines did, and the Chinese crossbow was a more advanced device than its Western counterpart. European crossbows used a revolving nut and a single-lever trigger, while Chinese crossbows had a precisely made, three-piece bronze mechanism including "an intermediate lever that allowed the bowman to fire a heavy bow with a short, crisp, and light pull on the trigger.

– David Graff

When Europeans started using crossbows in battles in the 900s AD, their triggers were more awkward, and the bows were made of wood. However, by the 1200s, European crossbows also started using composite bows, making them more powerful. From the 1200s onwards, European crossbows used loading mechanisms not seen in China, such as pulleys, gaffles, cranequins, and screws. Also, by the 1300s, European crossbows could be made of steel, making them even stronger than the heaviest Chinese infantry crossbows. But the power stroke of European crossbows remained much shorter than Chinese ones, which limited their power despite the heavier draw weights.

For example, a 68-kilogram (150-pound) draw crossbow with an 11-inch power stroke can shoot a 26-gram (400-grain) arrow at 62 meters per second (205 feet per second). But a 68-kilogram (150-pound) draw crossbow with a 12-inch power stroke can shoot the same arrow at 72 meters per second (235 feet per second). This means a small increase in power stroke leads to a much bigger increase in power. So, a standard Han Dynasty crossbow with a 175-kilogram (387-pound) draw weight and a 51-centimeter (20-21 inch) power stroke would have similar power to a medieval European crossbow with a 544-kilogram (1,200-pound) draw weight and a 15-18 centimeter (6-7 inch) power stroke.

European crossbows were replaced by arquebuses and muskets in the 1500s. In China, the crossbow was not seen as a serious military weapon by the end of the Ming dynasty, but it was still used a little bit into the 1800s.

| Chinese (7th c. BC-) | Gastraphetes (5th c. BC) | Arcuballista (4th c. AD) | European (10th c.) | European (13th c.) | European (late 14th c.) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bow length (cm) | 70-145 | 99 | 122 | 58-91 | 80 | |

| Tiller length (cm) | 60-70 | 25.5 | 95.5 | |||

| Power stroke (cm) | 46-51 | 41 | 10-18 | 16 | ||

| Draw-weight (kg) | 68-340 | 55-90 | 20.5 | 36-90 | 90-270 | 180-680 |

| Range (m) | 170-450 | 230 | 91.5 | 340-411 | ||

| Lock mechanism | bronze vertical trigger | bronze block and lever | rolling nut – bone, antler | rolling nut | rolling nut – metal | |

| Spanning device | winch, stirrup (12th c.), belt claw (late) |

claw & lever | stirrup (12th c.), belt claw (12th c.) |

winch | winch pulleys, gaffle, cranequin, screw, cord pulley (15th c.) |

|

| Crossbow material | composite | composite | wood | composite | steel | |

| Repeating crossbow material | mulberry wood/bamboo |

Japan

Oyumi were ancient Japanese artillery weapons that first appeared in the 600s. Japanese records say the Oyumi was different from the handheld crossbows also used at the time. A quote from the 600s suggests that the Oyumi might have been able to fire many arrows at once: "the Oyumi were lined up and fired randomly, the arrows fell like rain." A Japanese artisan in the 800s claimed to have improved a Chinese version of the weapon; his version could rotate and fire in multiple directions. The last time the Oyumi was recorded as being used was in 1189.

Islamic World

There are no mentions of crossbows in Islamic texts before the 1300s AD. Arabs generally didn't like the crossbow and saw it as a foreign weapon. They called it qaus al-rijl (foot-drawn bow), qaus al-zanbūrak (bolt bow), and qaus al-faranjīyah (Frankish bow). While Muslims did have crossbows, there seem to be differences between eastern and western types. Muslims in Spain used the typical European trigger, while eastern Muslim crossbows had a more complex trigger.

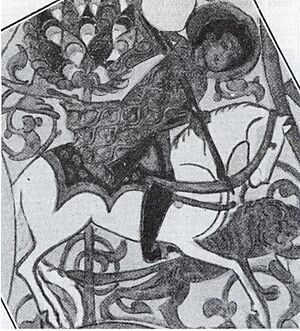

Mamluk cavalry (soldiers on horseback) used crossbows.

Africa and South America

In Central Africa, simple crossbows were used for hunting and as a scout weapon. They were especially used by different pygmy tribes, often with poisoned and small arrows. This quiet hunting method in the tropical forest is similar to how some South American indigenous people hunt with blowpipes and poisoned arrows. It helps avoid scaring the prey, especially if the first shot misses. Since the small arrow itself is rarely deadly, the animal will fall from the trees after some time due to the poison.

In the American South, the crossbow was used by the conquistadors (Spanish explorers and conquerors) for hunting and fighting when firearms or gunpowder were not available due to money problems or being isolated.

Crossbows Today

Today, crossbows are mostly used for target shooting in modern archery. In some countries, they are still used for hunting, like in most parts of the United States, and some areas in Asia, Europe, Australia, and Africa. Crossbows with special projectiles are used in whale research to take blubber biopsy samples without harming the whales.

Modern Military and Other Uses

Crossbows were eventually replaced in warfare by gunpowder weapons, even though early guns were slower to fire and less accurate than crossbows at first. The Battle of Cerignola in 1503 AD was largely won by Spain using matchlock firearms, marking the first time a major battle was won mainly by guns. While the military crossbow was mostly replaced by firearms by 1525 AD, the sporting crossbow remained a popular hunting weapon in Europe until the 1700s.

A bomb-throwing crossbow called the Sauterelle was used by the French and British armies on the Western Front during World War I. It could throw a grenade 110–140 meters (120–153 yards).

Crossbows are still used today by some militaries, tribal forces, and even police forces in China. Since their use is not as restricted as firearms, they are used as silent weapons and for their psychological effect, sometimes with poisoned projectiles. Crossbows are used for ambushes, anti-sniper operations, or with ropes to set up zip-lines in difficult areas.

Images for kids

-

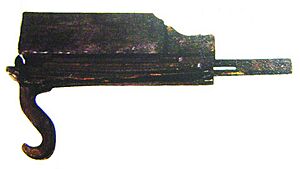

Warring States crossbow

-

Warring States or Han dynasty crossbow trigger and buttplate

-

Warring States or Han Dynasty crossbow trigger and buttplate made of bronze and inlaid with silver.

-

Warring States or Han Dynasty crossbow trigger and buttplate made of bronze and inlaid with silver.

-

Large crossbow trigger (23.49 x 17.78 cm) for mounted crossbows, Han dynasty

-

Modern depiction of a Warring States Mohist siege crossbow

-

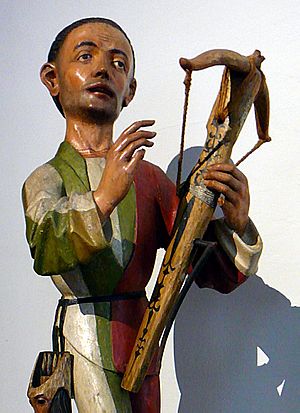

Statue of Cao Lỗ holding the magical crossbow he built for An Dương Vương

-

Khmer elephant mounted crossbow

-

10th century depiction of a gastraphetes

-

The gastraphetes among other ancient mechanical artillery

-

Gastraphetes being armed

-

Mounted version of a gastraphetes

-

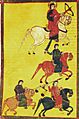

Earliest European depiction of cavalry using crossbows, from the Catalan manuscript Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse, 1086.

-

Man hunting with a crossbow in Spain, 12th century

-

Leonardo da Vinci's giant crossbow, late 15th to early 16th century

-

Crossbow of Matthias Corvinus, 1489

See also

- Hymn to the Fallen (Jiu Ge)

- Medieval warfare

- Panjagan, a possible crossbow type Sasanian weapon

| Tommie Smith |

| Simone Manuel |

| Shani Davis |

| Simone Biles |

| Alice Coachman |