History of the Encyclopædia Britannica facts for kids

The Encyclopædia Britannica is a very famous collection of knowledge that has been published continuously since 1768. It has come out in fifteen main versions, called "editions." Over the years, some editions were updated with extra books called "supplements," or they were completely reorganized. More recently, the Britannica has also become available online and on CDs or DVDs. Since the 1930s, the Britannica has created other products, using its reputation as a trusted source of information and a great learning tool.

The printed versions of the encyclopedia stopped in 2012 because they were losing money. However, the Britannica continues to be available and updated on the internet.

Contents

Early Encyclopedias and the Britannica's Start (1768–1824)

What is an Encyclopedia?

People have been creating encyclopedias for a very long time, even since ancient times. Early examples include the works of Aristotle and the Natural History by Pliny the Elder, which had thousands of articles. During the Middle Ages, encyclopedias were published in Europe and China. Most early encyclopedias were written in Latin and didn't include stories about living people.

In the 1700s, English encyclopedias started to appear. One of the first was Lexicon Technicum by John Harris in 1704, which even had articles by famous people like Isaac Newton. Later, Ephraim Chambers wrote a very popular Cyclopedia in 1728. This showed publishers that encyclopedias could be very successful.

The First Edition of Britannica (1771)

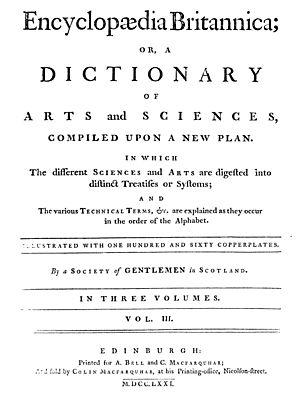

The idea for the Britannica came from Colin Macfarquhar, a bookseller, and Andrew Bell, an engraver, both from Edinburgh, Scotland. They wanted to create a new encyclopedia that was different from the French Encyclopédie, which some people thought was too radical.

They hired William Smellie, a 28-year-old scholar, to be the editor. He was paid 200 pounds to create the encyclopedia in 100 parts, which were later put together into three large books. The first part came out on December 10, 1768. The Britannica was published under the name "A Society of Gentlemen in Scotland." It was finished in 1771, with 2,391 pages. About 3,000 sets were sold for 12 pounds each.

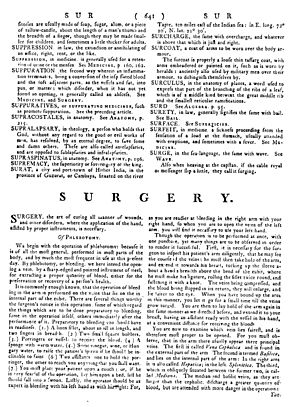

The first edition had 160 copperplate pictures drawn by Bell. Some of these pictures, showing childbirth, were so detailed that some readers actually tore them out!

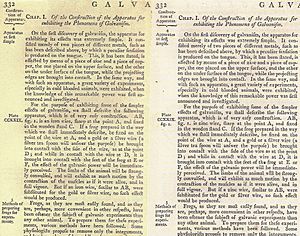

What made the Britannica special was its "new plan." Instead of listing every related term separately, it grouped similar topics into longer, more detailed essays. For example, all information about "dogs" wouldn't be scattered under "poodle," "terrier," etc., but would be in one big article about "Dogs." This made it easier to learn about a whole subject. Smellie wrote most of the first edition, using ideas from famous writers like Voltaire and Benjamin Franklin.

Smellie believed that publications should always be useful. He said that if a book isn't useful, it and its authors don't deserve praise.

Second Edition and Its Updates (1783)

After the first edition was a success, a bigger second edition was started in 1776. This time, it included articles on history and biographies of people. Smellie didn't want to be the editor because he didn't like adding biographies. So, Macfarquhar took over, helped by James Tytler, who was a good writer and worked for little pay. Tytler wrote many science and history articles.

The second edition was much larger, with ten volumes, 8,595 pages, and 340 pictures. It had five times as many long articles as the first edition. For example, the article on "Medicine" was 309 pages long!

This edition was a big improvement, but it still had some old-fashioned information. For instance, the "Chemistry" article talked about phlogiston, an old idea about how things burn. Tytler even described Noah's Ark in detail!

The second edition was a financial success, selling over 1,500 copies. This encouraged the publishers to create an even more ambitious third edition. Because it took a long time to write, later volumes were more up-to-date. For example, the 1783 volume mentioned Virginia as "now one of the United States," but an earlier volume from 1778 described Boston before the American Revolutionary War.

Third Edition and Its Growth (1797)

The third edition was published from 1788 to 1797. It came out in 300 weekly parts and was later bound into 18 volumes. It had 14,579 pages and 542 pictures. Colin Macfarquhar edited it until he died in 1793, and then George Gleig took over. James Tytler also wrote a lot for this edition.

This edition nearly doubled the size of the second. Many important experts contributed, like Dr. Thomas Thomson, who introduced modern chemistry ideas. The third edition became a very important and trusted reference book for many years. It was also very profitable, making about 42,000 pounds in profit from selling around 10,000 copies. This edition also started the tradition of dedicating the Britannica to the British king, then King George III.

Interestingly, the third edition had a controversial article on "Motion" that incorrectly rejected Isaac Newton's theory of gravitation. Instead, it suggested that gravity was caused by the classical element of fire.

The first American encyclopedia, Dobson's Encyclopædia, was based almost entirely on this third edition of the Britannica. It was published around the same time (1788–1798).

Later Early Editions (4th, 5th, 6th)

The fourth edition was published from 1800 to 1810, with 20 volumes. Dr. James Millar was the editor. This edition was a small expansion of the third, updating some history, science, and biography articles. Some long articles were completely rewritten, like "Botany" and "Chemistry."

The fifth edition (1817) was mostly a corrected reprint of the fourth edition. It was one of the last English publications to use the old-fashioned "long s" letter (ſ).

The sixth edition (1823) was also a reprint of the fifth, but it used a modern typeface without the long s. Charles Maclaren was the editor.

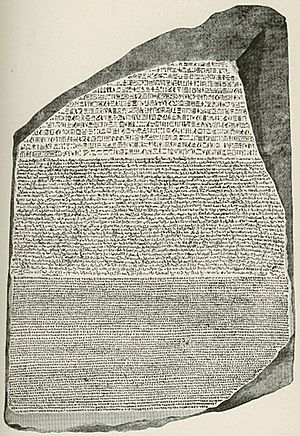

During these years, there were also supplements published to keep the encyclopedia up-to-date. The supplement to the fifth edition (1824) was very important. It had famous contributors like Sir Walter Scott, who wrote articles on "Chivalry" and "Romance." Thomas Young's article on Egypt even included the translation of the hieroglyphics from the Rosetta Stone.

Unfortunately, the owner, Archibald Constable, went bankrupt in 1826. The rights to the Britannica were sold, and eventually, the Edinburgh publishing company A & C Black took over. By this time, the Britannica needed a big update, as many articles were very old.

A. and C. Black Editions (1827–1901)

Seventh Edition: A Fresh Start (1842)

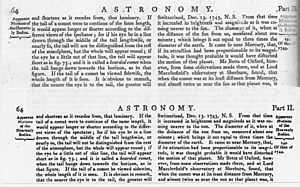

The seventh edition was a completely new work, not just a revision of older ones. It was published from 1830 to 1842 and had 21 volumes. Macvey Napier was the editor. This was the first edition to have a general index for all articles, which made it much easier to find information. Many famous people contributed, including Sir David Brewster and Robert Stephenson. For the first time, mathematical diagrams and illustrations were printed directly on the same pages as the text.

Even though it cost a lot to produce, about £108,766, around 5,000 sets were sold.

Eighth Edition: More Revisions (1860)

The eighth edition was published from 1853 to 1860, also in 21 volumes. Dr. Thomas Stewart Traill was the editor. This edition was a thorough revision, with most articles rewritten and new ones added by famous contributors. There were 344 contributors in total, including Lord Macaulay and Charles Kingsley. The topic of Photography was listed for the first time.

To save money, this edition had fewer pictures and maps than the seventh.

Ninth Edition: The Scholar's Edition (1875–1889)

The ninth edition, often called "the Scholar's Edition," was published from 1875 to 1889 in 25 volumes. Thomas Spencer Baynes was the first English-born editor. Later, W. Robertson Smith took over. This edition is highly praised for its excellent scholarship.

It had many famous contributors, such as Thomas Henry Huxley (who wrote about "Evolution"), Lord Rayleigh (on "Optics"), and Prince Kropotkin (on "Moscow"). There were about 1100 contributors, including some women. This edition was also the first to have a major article about women's legal rights. The topic of Evolution was included for the first time, following Charles Darwin's ideas.

The ninth edition was much more luxurious than previous ones, with high-quality paper and leather bindings. It made great use of new printing technology, with thousands of good illustrations printed directly within the text. This edition was a big success, selling about 8,500 sets in Britain.

American companies were allowed to print and sell copies in the United States, making them identical to the British sets. However, many unauthorized, cheaper copies were also sold in the U.S. because there were no strong copyright laws protecting foreign books. Some people even stole proofreader copies to publish their versions at half the price!

In 1896, the authorized American publishers managed to get court orders to stop the illegal copies. But some companies got around this by rewriting the copyrighted articles.

In 1901, the rights to the Britannica were sold to American businessmen Horace Everett Hooper and Walter Montgomery Jackson. This sale caused some lasting upset among British citizens who felt that American interests were now too important.

First American Editions (1901–1973)

Tenth Edition: A Supplement (1902-1903)

The new American owners quickly created an 11-volume supplement to the ninth edition. Together, these 35 volumes were called the "10th edition." Hugh Chisholm was one of the main editors.

Famous people like Ludwig Boltzmann, Walter Camp (who wrote about "Base-ball"), and John Muir (who wrote about "Yosemite") contributed.

However, many articles from the ninth edition were over 25 years old, so some people were upset that it was called a "new" edition. This led to a popular joke: "The Times is behind the Encyclopædia Britannica and the Encyclopædia Britannica is behind the times."

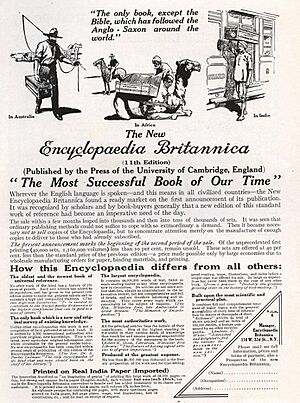

Despite this, the advertising campaign for the tenth edition was very successful, selling over 70,000 sets and making a lot of profit.

Eleventh Edition: A New Standard (1910)

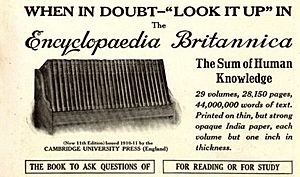

The famous eleventh edition was started in 1903 and published all at once in 1910–1911, with 28 volumes and a separate index. It was edited by Hugh Chisholm in London and Franklin Henry Hooper in New York. This edition is still highly respected for its clear explanations of scholarly topics. Since it's now in the public domain, you can find the full text online for free.

The eleventh edition kept the high quality of the ninth but also had shorter, simpler articles that were easier for regular readers to understand. This helped make the Britannica popular for a wider audience while still being a great reference book. The high quality was largely thanks to the owner, Horace Everett Hooper, who spent a lot of money to make it excellent.

After some legal arguments, Hooper became the sole owner. The Times newspaper stopped sponsoring it, but Hooper got Cambridge University as a new sponsor. Later, it was licensed to Sears Roebuck and Co. in Chicago, who made a smaller, "handy edition." The owner of Sears, Julius Rosenwald, saved the Britannica from bankruptcy several times.

The eleventh edition had 35 named female contributors out of 1500, which was seen as a big step forward for recognizing women's contributions. Hundreds of other women also wrote unsigned articles. Sales of this edition were much higher than previous ones, especially in the United States, which had grown a lot since 1768.

Twelfth and Thirteenth Editions (1922, 1926)

Poor sales during World War I almost led to the Britannica going bankrupt. In 1920, Julius Rosenwald of Sears Roebuck bought the rights.

In 1922, a 3-volume supplement was released to cover events before, during, and after World War I. These volumes, combined with the eleventh edition, became the twelfth edition. This edition was not a commercial success.

In 1926, the Britannica released three new volumes covering 1910–1926, replacing the previous supplement. These new volumes, with the eleventh edition, became the thirteenth edition. This edition had many famous contributors, including Harry Houdini, Albert Einstein, Marie Curie, Sigmund Freud, and Henry Ford.

Fourteenth Edition (1929)

By 1926, the eleventh edition was getting old, so work began on a new one. The fourteenth edition was completed in three years, costing $2.5 million, all paid for by Julius Rosenwald. It had 24 volumes (down from 29) but more articles (45,000 compared to 37,000). It also had 15,000 illustrations.

This edition was different from the eleventh, with fewer volumes and simpler articles, aiming for a wider American audience. It also had many famous contributors, including eighteen Nobel laureates in science. Popular entertainment was covered more, with articles on boxing by Gene Tunney and ballroom dancing by Irene Castle. About half of its 3500 contributors were American.

The fourteenth edition was published in September 1929. Unfortunately, the Great Depression started just a month later, and sales dropped sharply. Despite support from Sears Roebuck, the Britannica almost went bankrupt again. In 1932, its headquarters moved to Chicago, where they remain today.

Continuous Revision Policy

To prevent sales from dropping between new editions, Elkan Harrison Powell, the new President of the Britannica, introduced a policy of "continuous revision" in 1933. The idea was to have a team of editors constantly updating articles on a fixed schedule. This way, the Britannica would always be up-to-date and ready to sell. New printings would be made every year with only enough copies to cover sales for that year.

Powell also started the Britannica's "Book of the Year," a single volume released every year covering new developments in science, technology, culture, and politics. He also introduced the Library Research Service, where Britannica owners could get their questions answered by the editorial staff.

Under Powell, the Britannica also created "spin-off" products, like Britannica Junior for children (1934) and the Encyclopædia Britannica World Atlas (1942).

New Ownership (1943)

Sears Roebuck published the Britannica until 1943. In 1941, Sears offered to give the rights to the University of Chicago, but the university declined.

So, in 1943, William Benton, a wealthy former U.S. senator, took control of the Britannica. He published it until his death in 1973. His widow, Helen Hemingway Benton, continued until her death in 1974. The Benton Foundation managed the Britannica until it was sold in 1996 to Jacqui Safra.

The Fifteenth Edition (1974–2010)

A New Structure (1974)

Even with continuous revision, the fourteenth edition eventually became outdated. So, in the early 1960s, work began on a new, fifteenth edition. It was released in 1974 after ten years of work and costing $32 million.

This new Encyclopædia Britannica (also called Britannica 3) had a unique three-part structure:

- A single Propædia volume, which was an outline of all knowledge.

- A 10-volume Micropædia with over 100,000 short articles (under 750 words).

- A 19-volume Macropædia with over 4,000 longer, detailed articles with references.

Unlike previous editions, this fifteenth edition did not have a general index. The idea was that the Propædia and Micropædia would serve as the index. However, many readers found this confusing and criticized the unusual organization. It was hard to know if a topic would be in the Micropædia (short articles) or the Macropædia (long articles).

Restoring the Index (1985)

In 1985, the Britannica listened to its readers and brought back the index as a two-volume set. The number of topics in the index grew over time.

The 1985 version of the fifteenth edition also made other big changes. The many articles in the Macropædia were combined into fewer, longer articles. For example, all the articles for the 50 U.S. states were merged into one 310-page article called "United States of America." The Macropædia was reduced from 19 to 17 volumes, and the Micropædia grew from 10 to 12 volumes, though it had fewer articles overall. The strict word limit for Micropædia articles was also relaxed.

On March 14, 2012, Britannica announced that it would no longer print paper versions of its encyclopedia, as they made up less than 1% of its sales. The company decided to focus on its DVD and online versions instead.

The Global Edition (2009)

The Britannica Global Edition was printed in 2009. It had 30 volumes and over 18,000 pages, with 8,500 pictures, maps, and illustrations. It contained over 40,000 articles written by experts from around the world, including Nobel Prize winners. Unlike the fifteenth edition, it went back to the traditional A-through-Z organization, like editions up to the fourteenth. The last printing of this edition was in 2011, and it is now sold out.

Electronic Versions of Britannica

In the 1980s, Microsoft wanted to work with Britannica to create a CD-ROM encyclopedia. However, Britannica's leaders were confident in their print sales and turned down the offer. They didn't think a CD-ROM could compete with their expensive, high-quality books. Microsoft then created its own encyclopedia, Encarta, using content from another source.

In 1981, the first digital version of the Britannica was made for an online service called LexisNexis.

By 1990, Britannica's sales reached a high of $650 million. But when Encarta was released in 1993 and often came free with new computers, Britannica's sales dropped sharply. Britannica responded by offering a CD-ROM version, but it was expensive.

In 1994, an online version was launched. By 1996, the price of the CD-ROM had dropped, and sales were cut in half. Facing financial trouble, Britannica was bought in 1996 by Swiss financier Jacob Safra. He cut prices drastically to compete with Encarta, even offering the entire encyclopedia for free online for about 18 months.

Some former editors believe that Britannica failed to take advantage of its early lead in electronic encyclopedias. They think this was because the company's sales staff, who earned commissions from selling print books door-to-door, had too much influence on decisions about digital products.

After stopping its print edition, which brought in very little money, Britannica hoped to move to CD or online versions. However, sales of these were also disappointing, partly due to competition from Wikipedia. Sales of the CD/DVD version ended with the 2015 "Ultimate Reference Suite."

See also

In Spanish: Historia de la Encyclopædia Britannica para niños

In Spanish: Historia de la Encyclopædia Britannica para niños

| William L. Dawson |

| W. E. B. Du Bois |

| Harry Belafonte |