Hundred Years' War, 1337–1360 facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Edwardian War (1337–1353) |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Hundred Years' War | |||||||

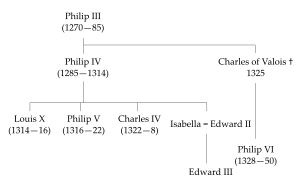

The Battle of Crécy in 1346 (Jean Froissart's Chronicles) |

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

The Edwardian War was the first part of the Hundred Years' War. This big conflict between England and France lasted from 1337 to 1360. It's called the Edwardian War because Edward III of England started it. He believed he should be the King of France.

This war began because of two main reasons. First, there were disagreements over who controlled Aquitaine in France. Edward was the Duke of Aquitaine, which meant he was a vassal (a lord who owes loyalty) to the French King. Second, Edward III claimed he had a right to be the King of France. During this part of the war, England and its allies were mostly victorious.

Edward had inherited the region of Aquitaine. He first accepted Philip VI of France as the new French King. But things got bad when Philip became friends with Edward's enemy, David II of Scotland. Edward then gave safety to Robert III of Artois, a French person who was wanted by Philip. When Edward refused to send Robert back, Philip took control of Aquitaine. This started the war. In 1340, Edward declared himself King of France.

Edward III and his son, Edward the Black Prince, led successful campaigns across France. They won important battles at Auberoche (1345), Crécy (1346), and La Roche-Derrien (1347). They also captured Calais in 1347. The fighting then stopped for a few years because of the terrible Black Death plague.

War started again in the mid-1350s. The English won a big victory at the Battle of Poitiers in 1356. The French King, John II, was captured and held for ransom. A truce was signed in 1357, followed by two treaties in London in 1358 and 1359.

These treaties did not work out. Edward then started a new campaign towards Rheims. This campaign was not very successful. However, it led to the Treaty of Brétigny. In this treaty, Edward gave up his claim to the French throne. In return, he gained control over certain lands in France. A huge hailstorm, known as Black Monday (1360), hit the English army. This event helped push Edward III to agree to peace talks. This peace lasted for nine years. After that, a second part of the war began, called the Caroline War.

Contents

Why the War Started

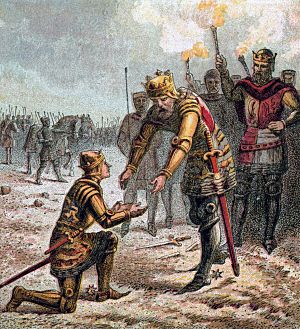

When Charles IV of France died in 1328, there was no clear male heir to the throne. Edward III of England was the closest male relative through his mother, Isabella of France. Isabella was Charles IV's sister. However, the question was if a woman could pass on a right to the throne that she herself could not hold.

French nobles decided that Philip, Count of Valois, was the closest male heir. He was Charles IV's cousin. So, Philip was crowned King Philip VI. This decision about who should be king was a main reason for the war. Edward III and later English kings continued to claim the French crown.

Edward III was seventeen when he became Duke of Aquitaine. He paid respect to Philip VI in 1329, as was expected. Gascony was a key part of the English lands in France. It was in southwest France, near the Pyrenees mountains. The people of Gascony had their own language and customs. They produced a lot of red wine, which they sold to England. This trade made a lot of money for the English king. The Gascons liked being connected to a distant English king. They preferred this to a French king who might interfere in their lives.

Even after Edward paid respect to Philip, the French still caused problems in Gascony. There were small fights in the walled towns along the Gascon border. French officials also put pressure on English areas. Philip also made deals with lords in Gascony. These lords promised to provide troops if there was a war with England.

France's support for Scotland also caused problems for England in the 1330s. In Flanders, towns needed English wool, but the nobles supported the French king. Philip also had a large fleet of ships. He had planned to go on a crusade. But in 1336, he moved his fleet to the English Channel. This was a clear threat to England.

One of Edward's important advisors was Robert III of Artois. Robert was an exile from the French court. He had argued with Philip VI over an inheritance. In November 1336, Philip demanded that Robert be sent back to France. If not, Philip warned of "great danger and disagreement." The next year, Philip took Edward's lands in Gascony and Ponthieu. He said Robert of Artois was one of the reasons for this action.

Early Fighting in the Low Countries (1337–1341)

Philip VI taking Gascony started the war in 1337. Edward's plan was for his forces in Gascony to hold their ground. Meanwhile, his main army would invade France from the north. Edward promised to pay his allies on the continent a lot of money. To pay for the war, Edward needed huge amounts of money. He borrowed heavily from rich bankers.

Because Edward was busy raising money, his invasion plans were delayed. This allowed the French to use their forces elsewhere. In December 1338, the French invaded Gascony. They captured Saint-Macaire and Blaye. The English leader in Gascony, Oliver Ingham, was a skilled soldier. He received no troops or money from England. He had to rely on local resources. His plan was to defend castles as best he could.

The English parliament tried to gather ships for two naval fleets. But this did not happen quickly enough. So, the French, who had hired ships from Genoa, attacked the English coast. Portsmouth was raided, Southampton was looted, and Guernsey was captured. The French naval campaign continued in July 1339. They planned a big raid on the Cinque Ports. However, English forces were waiting for them. The French then sailed to Rye and raided that area.

Finally, the English put together two fleets. They arrived to face the French. The French, thinking the English fleet was larger, sailed away without a fight. In August, the French naval campaign ended. The Genoese crews argued over pay and returned to Italy.

English coastal defenses were mostly successful against French raids. But many English soldiers went to France or defended the coast. This left fewer troops in the north and Scotland. With fewer English soldiers, the Scots recaptured many places. These included Perth in 1339 and Edinburgh in 1341.

Edward desperately needed some victories. In September, he gathered about 12,000 men in the Low Countries. His army included soldiers from his allies. On September 20, Edward's army marched into the area of Cambrai. They besieged Cambrai for two weeks. The area was destroyed, but Cambrai was not captured. On October 9, Edward's army moved into France.

While Edward was besieging Cambrai, the French king gathered his army. The French army moved close to the border. Edward's army destroyed many villages. Philip's army followed Edward's army. On October 14, Edward moved towards the French army. A battle seemed likely. But Edward moved away again, plundering more land. The French continued to follow. Both armies faced each other in Picardy. A battle was expected on October 23, but it did not happen. Edward marched his troops out of France. The French did not chase them. This ended the campaign.

The ruler of Flanders was loyal to the French king. So, Edward stopped all English goods from going to Flanders. In 1337, this caused a revolt in Flanders. The people lacked English wool and food. The leader of the revolt, Jacob van Artevelde, arranged for Flanders to be neutral. In return, England lifted its trade ban. By December, the Flemish people were ready to join the anti-French side. The cities of Ghent, Ypres, and Bruges declared Edward King of France. Edward wanted to strengthen his alliances. His supporters could say they were loyal to the "true" king of France. In February 1340, Edward returned to England to raise more money.

English defenses in Gascony were very weak. But help came when two French-supporting nobles started fighting each other. These were the Count of Armagnac and the Count of Foix. Also, the Albret family helped. Bernard-Aiz, Lord of Albret, declared his support for Edward in 1339. The Albrets were very important in English Gascony. They helped Edward pay for his campaign and find more soldiers.

In 1340, the French gathered an invasion fleet. It included French, Castilian, and Genoese ships. About 400 ships were in the Zwyn estuary. The English did not have special warships. They used large merchant ships called cogs, which were changed for naval battles. Edward gathered his fleet and set up his headquarters on the ship Thomas. He knew the French fleet was much stronger. But he sailed on June 22 to face them.

The French fleet took a defensive position near the port of Sluys. They may have been trying to stop Edward from landing his army. The English fleet seemed to trick the French into thinking they were leaving. But when the wind changed, the English attacked. They had the wind and sun behind them. Edward sent his ships in groups of three. Two ships were full of archers, and one was full of men-at-arms. The French ships were very close together, which made it hard for them to move. The English archers would shoot arrows onto the French decks. Then the men-at-arms would finish the fight. The French fleet was almost completely destroyed in the Battle of Sluys. After this, England controlled the English Channel for the rest of the war. This stopped French invasions.

In spring 1340, Philip VI planned to break the anti-French alliance. He attacked Hainaut in May. But when he heard about the disaster at Sluys, he changed his focus. Edward III split his army. The first part, led by Robert of Artois, invaded Artois. But in a battle near Saint-Omer on June 26, most of this army was destroyed. Robert had to retreat. On the same day, Edward III arrived at the walls of Tournai. (This city is now in Belgium, but then it was one of France's largest cities.) The siege lasted a long time. In September, Philip VI arrived with the main French army. Philip VI again refused to fight the English in a big battle. Both sides were running out of money. This led to a temporary truce, called the Truce of Espléchin, on September 25, 1340.

The Truce of Espléchin ended the first part of the Hundred Years' War. It stopped fighting on all fronts for nine months. The war had cost a lot of money and caused many problems. Grand alliances were too expensive. Some allies could no longer be trusted. German princes left the anti-French alliance. Only the people of Flanders remained. In England, people started to turn against Edward. His gains in Europe had cost a lot, and most of Scotland was lost. Edward was almost broke and had to cut his losses. He repaid those whose support he needed. But others were not repaid.

Fighting in Brittany (1341–1345)

On April 30, 1341, John III, Duke of Brittany, died without children. This started the Breton war of succession. John III left two people who could become duke. One was his younger half-brother, John, Count of Montfort. The other was his niece, Jeanne of Penthièvre. Jeanne was the daughter of his brother Guy. Jeanne was more closely related to John III. But new rules about women inheriting titles seemed to mean women could not become powerful rulers. Jeanne of Penthièvre's husband was the King's nephew, Charles of Blois.

Under feudal law, the King of France was supposed to decide who should inherit. John of Montfort did not trust the King to be fair. So, he took the title himself. He captured Nantes, the capital of Brittany. He also called on the knights of Brittany to recognize him as Duke. The French-speaking nobles and bishops refused to recognize John of Montfort. But the local clergy, knights, and farmers did. This led to a civil war.

After taking Nantes, John of Montfort also seized the ducal treasury. By mid-August, he controlled most of the duchy. This included the three main cities: Nantes, Rennes, and Vannes. Philip of France supported Charles of Blois as the official candidate. John of Montfort feared the French army would remove him. So, he fled to England to ask Edward III for help.

Edward III agreed to help, even though the Truce of Espléchin was still in place. John of Montfort returned to Brittany. He waited for confirmation of English help. Meanwhile, Philip VI sent a large army to Brittany to support Charles of Blois. By November, they had trapped John of Montfort in Nantes. The people of Nantes decided to surrender John of Montfort to the French army. He was then imprisoned in Paris.

Now, John's wife, Joanna of Flanders, took charge of his cause. She set up her base at Hennebont in southern Brittany. She defended it against Charles de Blois' army through the winter of 1341–42. Her forces kept the road open between Brest and Hennebont. This allowed a small English force to land at Brest. They joined her forces and drove the French army away. They also recaptured land in western Brittany.

In August 1342, another English force arrived at Brest. It was led by the Earl of Northampton. This force moved across Brittany and captured Vannes. English forces, with soldiers led by Richard de Artois, defeated a French army. This French army was led by Charles of Blois near Morlaix on September 30, 1342. Robert de Artois sailed to England. He died from wounds he got when taking Vannes. Even worse for Edward III, Vannes was retaken by a French force. This force was led by Olivier of Clisson.

In late October 1342, Edward III arrived with his main army at Brest. He retook Vannes. He then moved east to besiege Rennes. A French army marched to fight him. But a big battle was avoided. Two cardinals arrived from Avignon in January 1343. They forced a general truce, called the Truce of Malestroit. Even with the truce, the war continued in Brittany. It lasted until May 1345, when Edward finally gained control.

Truce and Challenges (1343–1345)

The official reason for such a long truce was to allow time for peace talks. Both countries were tired of war. In England, taxes had been very high. The wool trade had also been difficult. Edward III spent the next few years slowly paying off his huge debts.

In France, Philip VI also had money problems. France did not have one central group that could approve taxes for the whole country. Instead, the King had to negotiate with different local assemblies. Most of them refused to pay taxes while there was a truce. So, Philip VI had to change the value of money. He also introduced two very unpopular taxes. One was the 'fouage', or hearth tax (a tax on each home). The other was the 'gabelle', a tax on salt.

During this truce, many soldiers became unemployed. Instead of going back to poverty, they formed groups called free companies or routiers. These groups were made up of men from Gascony, Brittany, and other parts of France, Spain, Germany, and England. They used their military skills to live off the land. They would rob, loot, kill, or torture people to get supplies. With the Malestroit truce in place, these routier groups became a bigger problem. They were well organized. Sometimes they worked as mercenaries for one or both sides. One tactic was to seize a town or castle. From this base, they would plunder the areas around it. They would keep doing this until there was nothing left of value. Then they would move to new places. Often, they would hold towns for ransom. The towns would pay them to leave. The problem of the routiers was not solved until the 15th century. A new tax system allowed for a regular army that hired the best of these routiers.

English Victories Continue (1345–1351)

On July 5, 1346, Edward sailed from Portsmouth. He had about 750 ships and 7,000 to 10,000 men. This was a major invasion across the English Channel. His son, Edward, the Black Prince, who was almost 16, was with him. On July 12, Edward landed in Normandy. The historian Jean Froissart wrote that when Edward landed, he fell down. His knights thought this was a bad sign. But Edward said, "This is a good sign for me, for the land desires to have me." Everyone was happy with his answer.

The army marched through Normandy. Philip gathered a large army to stop him. Edward chose to march north, destroying things as he went. He did not try to capture and hold land. During this time, he won two battles: the Storming of Caen and the Battle of Blanchetaque. Edward eventually found he could not outsmart Philip. So, he prepared his forces for battle. Philip's army attacked him at the famous Battle of Crécy. The much larger French army attacked in small groups. The skilled English and Welsh longbowmen defeated all these attacks. The French suffered heavy losses and had to retreat. Crécy was a huge defeat for the French.

Edward then moved north without anyone stopping him. He besieged the coastal city of Calais on the English Channel. He captured it in 1347. An English victory against Scotland in the Battle of Neville's Cross led to the capture of David II. This greatly reduced the threat from Scotland.

In 1348, the Black Death began to spread across Europe. This terrible plague had huge effects in both England and France. It stopped England from starting any major attacks. In France, Philip VI died in 1350. His son, John II ("John the Good"), became king.

At this time, there was bad feeling between the English and the Spanish. The Spanish had attacked and robbed English ships at sea. In 1350, the Spanish were in Flanders for trade. They heard the English planned to attack them on their way home. So, they prepared their ships with many weapons. They hired mercenaries, archers, and crossbowmen. When Edward heard this, he was angry. He said the Spanish had done many wrongs. He said they must be stopped. The Spanish fleet sailed along the south coast of England. They hoped to attack an unprepared town. Edward's fleet met them off Winchelsea on August 29, 1350. The battle lasted until dark. It was like a smaller version of Sluys. The archers killed many Spanish sailors. Then the English soldiers boarded their ships. Nearly half the Spanish ships were captured. The rest escaped in the dark.

French Government Problems (1351–1360)

Small fights continued in Brittany. There were also famous acts of chivalry, like the Battle of the Thirty in 1351. This battle was actually a planned tournament. There had been a truce since 1347, so no fighting was supposed to happen. Two opposing leaders, Robert de Beaumanoir (a Breton) and Richmond Bambro (an Englishman), agreed to a private fight. Thirty knights from each side fought with sharp weapons. Bambro's knights included famous soldiers like Robert Knolles and Hugh Calveley. But he could not find thirty Englishmen. So, he had to use German soldiers to make up the numbers. The battle lasted all day. It ended with a French victory. Following the rules of chivalry, the French ransomed many of the defeated English knights.

The Black Death reached England in 1348. The plague's widespread effects had put the war on hold. But by the mid-1350s, the disease had lessened. This allowed England to start rebuilding its money. So, in 1355, Edward's son, Edward the Black Prince, started the war again. He invaded France from English-held Gascony. By August of that year, he began a harsh campaign of raids called chevauchée. This campaign was meant to scare people and lower their spirits. It also aimed to make their leaders look bad and drain the French king's money. Anything that could be carried was stolen. Anything that could not be taken was broken or burned. An observer at the time said that as the Black Prince rode to Toulouse, "there was no town that he did not lay waste."

In August 1356, the Black Prince was threatened by a larger army led by John II. The English tried to retreat. But their way was blocked at Poitiers. The Black Prince tried to make a deal with the French. But John's army attacked the English on September 19, 1356. The English archers stopped the first three attacks of the French cavalry. The English archers were running out of arrows. Many were wounded or tired. The French king then sent in his best soldiers. It seemed the French would win. However, a Gascon noble named Captal de Buch managed to surprise the French. He led a small group of men around the side. They succeeded in capturing John II and many of his nobles. John signed a truce with Edward III. With John captured, much of the French government began to fall apart.

John's ransom was set at two million gold coins called écus. But John believed he was worth more. He insisted his ransom be raised to four million écus. The First Treaty of London was signed in 1358. It set John's ransom at four million écus. The first payment was due by November 1, 1358. However, the French did not make the payment. The Second Treaty of London was signed on March 12, 1359. This time, the treaty allowed hostages to be held instead of John. The hostages included two of his sons, several princes and nobles. Also, four people from Paris and two citizens from each of nineteen main towns in France were hostages. While these hostages were held, John returned to France. He tried to raise money to pay the ransom.

Also, under the treaty, England gained control of Normandy, Brittany, Anjou, Maine, and all the coastline from Flanders to Spain. This brought back the old Angevin Empire. The hostages were held in "honorable captivity." This meant they were allowed to move freely under the rules of chivalry. In 1362, John's son, Louis of Anjou, who was a hostage in English-held Calais, broke his promise and escaped. When John found out, he was ashamed of his son's actions. He felt it was his duty to return to captivity. He left Paris and gave himself up to the Captain of Calais. He was returned to his "honorable captivity" in England. He spent the rest of his time there. He died in London on April 8, 1364. John's funeral in England was a grand event. He was honored as a great man by the English royal family.

In 1358, a peasant revolt happened in France. It was called the Jacquerie. It was caused by the hardships the country people faced during the war. They were also treated badly by the free companies and the French nobles. This was especially true after the Battle of Poitiers. Led by Guillaume Kale, the peasants joined forces with other villages. Starting near Beauvais, north of Paris, they committed terrible acts against the nobles. They destroyed many castles in the area. All the rebellious groups were defeated later that summer at the battle of Mello. Punishments followed.

Edward took advantage of the unhappiness in France. He gathered his army at Calais in late summer 1359. His first goal was to take the city of Rheims. But the people of Rheims built up their city's defenses before Edward arrived. Edward besieged Rheims for five weeks. But the new defenses held strong. He stopped the siege and moved his army to Paris in spring 1360. The areas outside Paris were looted. But the city itself held out. Edward's army was weakened by attacks from French groups and by disease. After a few small fights, Edward moved his army to the town of Chartres.

At Chartres, disaster struck. A strange hailstorm hit Edward's army. It killed about 1,000 English soldiers and 6,000 horses. After this event, the King became very religious. He promised God to make peace with France. When the Dauphin (the French heir to the throne) offered to talk, Edward was ready to agree. Representatives from both sides met at Brétigny. Within a week, they agreed to a draft treaty. The Treaty of Brétigny was later signed by Kings John and Edward. It became the Treaty of Calais on October 24, 1360. Under this treaty, Edward agreed to give up his claim to the French crown. In return, he gained full control over a larger Aquitaine and Calais.

See also

In Spanish: Guerra de los Cien Años (1337-1360) para niños

In Spanish: Guerra de los Cien Años (1337-1360) para niños