Jean-Jacques Rousseau facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Jean-Jacques Rousseau

|

|

|---|---|

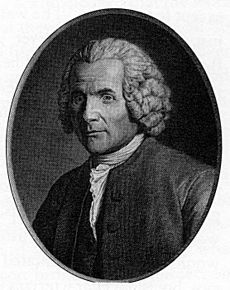

Rousseau by Maurice Quentin de La Tour, 1753

|

|

| Born | 28 June 1712 |

| Died | 2 July 1778 (aged 66) Ermenonville, France

|

| Era | 18th-century philosophy (Modern philosophy) |

| Region | Western philosophy |

| School | Social contract Romanticism |

|

Main interests

|

Political philosophy, music, education, literature, autobiography |

|

Notable ideas

|

General will, amour de soi, amour-propre, moral simplicity of humanity, child-centered learning, civil religion, popular sovereignty, positive liberty, public opinion |

| Signature | |

|

|

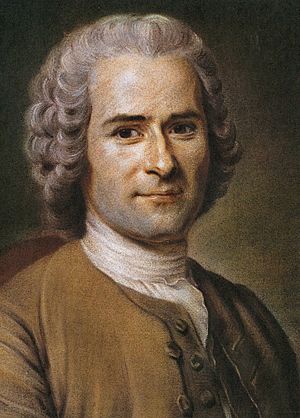

Jean-Jacques Rousseau (1712 – 2 July 1778) was a famous French-speaking philosopher. He was born in Geneva, Switzerland, and always said he was from Geneva. Rousseau lived in the 18th century during a time called the Age of Enlightenment. His ideas about politics greatly influenced the French Revolution. They also helped develop ideas like nationalism (strong loyalty to one's country) and socialist theories (ideas about fair sharing of wealth).

Rousseau was also a composer, meaning he wrote music. He wrote many books about music theory, which is the study of how music works. Rousseau wrote Confessions, which was his own life story. It was one of the first books of its kind. Many later philosophers were influenced by his ideas. He also wrote a novel called Julie, ou la nouvelle Héloïse, which was a bestseller. This book influenced writers of romanticism in the 19th century.

Rousseau believed that people were born good and innocent. He thought that bad things like corruption and sadness happened because of life experiences and living in society. He believed that if society was gone, people would be happy and pure again.

Rousseau is most famous for his "social contract" idea. This idea is often compared to the social contract ideas of John Locke. Rousseau explained his ideas in his book, The Social Contract.

During the French Revolution, Rousseau was very popular among a group called the Jacobin Club. He was buried as a national hero in the Panthéon in Paris in 1794, 16 years after he died.

Contents

Biography: Rousseau's Life Story

Early Life and Family

Rousseau was born in Geneva, which was a small city-state at the time. He often signed his books "Jean-Jacques Rousseau, Citizen of Geneva".

Geneva was supposed to be run "democratically" by its male citizens. But in reality, a few rich families controlled the city. Rousseau's father, Isaac Rousseau, was a watchmaker. He was also well-educated and loved music.

Rousseau's mother, Suzanne Bernard Rousseau, came from a wealthy family. She died shortly after Rousseau was born. Rousseau and his older brother, François, were raised by their father and an aunt. When Rousseau was five, his family moved to a neighborhood where many craftsmen lived.

Rousseau loved reading from a young age. He remembered reading adventure stories with his father every night. They would read so much that sometimes they would forget the time! After the novels, they read classic books. Rousseau's favorite was Plutarch's Lives of the Noble Greeks and Romans. He would read this book to his father while his father made watches.

When Rousseau was ten, his father had a legal problem and moved away. Jean-Jacques was left with his uncle. His uncle sent him to live with a minister for two years.

At age 13, Rousseau became an apprentice to a notary, then to an engraver. At 15, he ran away from Geneva because he was locked out of the city after curfew. He was on his own, as his father and uncle had mostly stopped supporting him. He worked as a servant, secretary, and tutor, traveling through Italy and France.

Becoming an Adult

When Rousseau was 20, he met Françoise-Louise de Warens, a kind noblewoman. Rousseau looked up to her and called her his "maman." She had a big library and loved music. She introduced Rousseau to many books and ideas. Rousseau started to study philosophy, math, and music seriously.

At 25, he received a small inheritance from his mother. He used some of it to pay back de Warens for her help. At 27, he got a job as a tutor in Lyon.

In 1742, Rousseau moved to Paris. He wanted to show the Académie des Sciences a new way to write music notes. He thought it would make him rich. The Academy did not think his system was practical, but they praised his musical knowledge. That year, he became friends with Denis Diderot. They often talked about writing.

From 1743 to 1744, Rousseau worked as a secretary for the French ambassador in Venice. This job was not well-paying, but it made him love Italian music, especially opera. His boss often paid his staff very late. After 11 months, Rousseau quit. This experience made him deeply dislike government rules and systems.

Life Back in Paris

When he returned to Paris, Rousseau was poor. He became friends with Thérèse Levasseur, a seamstress. She supported her mother and many siblings. Later, Rousseau took Thérèse and her mother in to live with him. He took on the responsibility of supporting her large family.

Starting in 1749, Rousseau wrote many articles for the famous Encyclopédie by Diderot and D'Alembert. His most famous article was about political economy, written in 1755.

Rousseau continued his interest in music. He wrote both the words and music for his opera Le devin du village (The Village Soothsayer). It was performed for King Louis XV in 1752. The king liked the opera so much that he offered Rousseau a lifelong pension (regular payments). But Rousseau turned down this great honor. This made him famous as "the man who had refused a king's pension." He also turned down other good offers, sometimes in a way that offended people.

Return to Geneva and New Ideas

Rousseau returned to Geneva in 1754. There, he finished his second major work, Discourse on the Origin and Basis of Inequality Among Men. This book expanded on ideas from his earlier work, Discourse on the Arts and Sciences.

Around this time, Rousseau stopped working with the Encyclopédie writers. He then wrote his three most important works. In these books, he strongly showed his belief that the human soul and the universe have a spiritual origin. During this time, rich and powerful nobles in France supported him.

Rousseau's long novel, Julie, ou la nouvelle Héloïse, was published in 1761. It was a huge success. In 1762, Rousseau published Du Contrat Social, Principes du droit politique (Of the Social Contract, Principles of Political Right).

In May 1762, Rousseau published Emile, or On Education. In this book, he suggested that all religions are equally good. He thought people should follow the religion they grew up with. This idea, called religious indifferentism, caused problems for Rousseau. His books were banned in France and Geneva. The Archbishop of Paris spoke against him, his books were burned, and warrants were issued for his arrest. This forced him to flee to Switzerland.

Life as a Fugitive

For over two years (1762–1765), Rousseau lived in Môtiers, reading, writing, and meeting visitors. But local ministers learned about some of his ideas they considered wrong. They decided he should not stay. One night, stones were thrown at the house where Rousseau was staying. His friends told him to leave the town.

Rousseau wanted to stay in Switzerland. He accepted an offer to move to a small, lonely island called the Île de St.-Pierre. Even though it was in a place he had been expelled from, he was told he could live there safely. He moved there on September 10, 1765. Even on this remote island, people came to visit him because he was famous.

However, on October 17, 1765, the government ordered Rousseau to leave the island and the area within 15 days. He asked for more time and offered to be put in jail with only a few books. But the government told him to leave the island within 24 hours. On October 29, 1765, he left the island and moved to Strasbourg. He then received invitations from several places in Europe. He soon decided to accept Hume's invitation to go to England.

Death and Legacy

Rousseau died from a stroke. He was buried on a small, wooded island called Île des Peupliers in a lake at Ermenonville. This place became a pilgrimage site for his many fans. On October 11, 1794, his remains were moved to the Panthéon in Paris. They were placed near those of Voltaire, another famous philosopher.

Rousseau's Philosophy: His Big Ideas

Understanding Human Nature

Rousseau believed that humans share two main traits with animals. One is amour de soi, which means the instinct to protect oneself. The other is pitié, which is feeling empathy or sympathy for others. He thought that only people who are morally lost would care only about how they compare to others. This leads to amour-propre, or vanity (being too proud).

Rousseau did not think humans were naturally better than other animals. However, he believed humans had a special ability to change their nature through free choice. They were not stuck with just their natural instincts.

Another thing that sets humans apart is their ability to improve. This means humans can make choices that make their lives better. These improvements can last and lead to positive changes for everyone, not just one person. This ability to improve, along with human freedom, allows humanity to evolve over time. But Rousseau also warned that this evolution might not always be for the better.

Ideas on Government and Society

Rousseau thought that the first types of government, like monarchies (rule by a king), aristocracies (rule by nobles), and democracies (rule by the people), all came from different levels of inequality in society. He believed these governments would always lead to even worse inequality. Eventually, a revolution would overthrow them, and new leaders would create even more unfair systems.

However, Rousseau also believed that humans could always improve themselves. Since humanity's problems came from political choices, he thought they could be fixed by a better political system.

His book The Social Contract explains how a fair government should work. It was published in 1762 and became one of the most important books on political ideas in the Western world. It built on some ideas he had written about earlier. In this book, Rousseau described a new political system that could help people regain their freedom.

Rousseau said that in a "state of nature" (before society), there were no laws or clear ideas of right and wrong. People left this state to get the benefits of working together. As society grew, things like dividing work and owning private property made laws necessary. In a later, less pure stage of society, people often competed with each other. They also became more dependent on others. This double pressure threatened both their survival and their freedom.

Rousseau believed that by joining together in a civil society through a social contract, people could protect themselves and stay free. This is because obeying the "general will" (the common good of all people) means individuals are not controlled by just a few others. It also means they are obeying laws they helped create as part of the group.

Rousseau thought that sovereignty (the power to make laws) should belong to the people. But he made a clear difference between the "sovereign" (the people's law-making power) and the "government" (the people who carry out the laws). The "sovereign" is the rule of law, ideally decided by direct democracy (where everyone votes on laws) in a meeting.

Rousseau did not like the idea of people exercising power through a representative assembly (where people elect others to make laws for them). He liked the idea of a city-state government, like Geneva, if it followed his principles. He thought France was too big to be an ideal state based on his ideas.

Education and Raising Children

Rousseau's ideas about education were not just about teaching facts. He focused on developing a child's character and moral sense. He wanted children to learn to control themselves and stay good, even in an unfair society. He believed a child should be raised in the countryside, which he thought was healthier than the city. A tutor would guide the child through different learning experiences.

Today, we might call this learning through "natural consequences." Rousseau felt that children learn right from wrong by seeing what happens after their actions, rather than through physical punishment. The tutor would make sure the child did not get hurt while learning.

Rousseau was an early supporter of education that fits a child's age. He divided childhood into stages:

- The first stage is up to about age 12. During this time, children are guided by their feelings and urges.

- The second stage is from 12 to about 16. In this stage, reason starts to develop.

- The third stage is from age 16 onwards. Here, the child grows into an adult.

Rousseau suggested that young adults learn a manual skill, like carpentry. This skill needs creativity and thought. It would keep them out of trouble and give them a way to earn a living if their situation changed. Rousseau's ideas have influenced modern "child-centered" education, which focuses on the child's needs and interests.

Rousseau as a Composer

Rousseau was a successful music composer. He wrote seven operas and other types of music. He also wrote about music theory. His music mixed the older Baroque style with the newer Classical style. He was part of the same generation of composers who helped music change. One of his most famous works is the opera The Village Soothsayer. He also wrote several well-known motets (choral pieces), some of which were performed in Paris.

Some of Rousseau's Musical Works

- Les Muses galantes (1743)

- Symphonie à Cors de Chasse (1751)

- Le Devin du village (1752) – an opera

- Salve Regina (1752) – a type of song

- Pygmalion (1762/1770) – a melodrama (a play with music)

- Avril – a song based on a poem

- Le Printemps de Vivaldi (1775)

Major Books and Writings

- Discourse on the Arts and Sciences (1750)

- Discourse on the Origin and Basis of Inequality Among Men (1754)

- Letter on French Music (1753)

- Discourse on Political Economy (1755)

- Julie or The New Heloise (1761) – a novel

- Emile or On Education (1762) – about education

- The Social Contract, or Principles of Political Right (1762) – about government

- Dictionary of Music (1767)

- Confessions of Jean-Jacques Rousseau (written 1770, published 1782) – his autobiography

- Essay on the Origin of Languages (published 1781)

- Reveries of the Solitary Walker (incomplete, published 1782)

Images for kids

-

Allegory of the French Revolution in honor of Rousseau, by Nicolas Henri Jeaurat de Bertry (1794). The final version of the painting was offered to the National Convention

See also

In Spanish: Jean-Jacques Rousseau para niños

In Spanish: Jean-Jacques Rousseau para niños

- List of political systems in France

- Rousseau Institute

- Rousseau's educational philosophy