José Luis Picardo facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

José Luis Picardo

|

|

|---|---|

| Born |

José Luis Picardo Castellón

18 June 1919 Jerez de la Frontera (Cádiz), Spain

|

| Died | 27 July 2010 (aged 91) Madrid, Spain

|

| Alma mater | Escuela Técnica Superior de Arquitectura de Madrid |

| Occupation | Architect |

| Years active | 1950–1995 |

| Spouse(s) | Trinidad de Ribera Talavera |

| Children | 5 |

| Awards |

|

| Buildings |

|

José Luis Picardo Castellón (born June 18, 1919 – died July 27, 2010) was a famous Spanish architect. He was also a talented muralist (someone who paints large wall murals), a draughtsman (someone who makes technical drawings), and an illustrator. Most people knew him simply as José Luis Picardo.

Picardo designed buildings in many different styles during his career. He created the modern headquarters for the Fundación Juan March in Madrid. He also designed the neo-Renaissance style School of Equestrian Art in Jerez de la Frontera. He even worked on many hotel projects for the Paradores de Turismo de España that looked like medieval castles.

Even when he was still studying architecture, he became known for his murals. He decorated many important modern buildings in Spain. His amazing drawing skills and understanding of perspective caught the eye of top architects after the Spanish Civil War. For several years, he drew illustrations, cartoons, and covers for major Spanish architectural magazines. He also designed the inside spaces, furniture, and lights for many of his buildings. Later in his life, he became an Academician (a member) of the Real Academia de Bellas Artes de San Fernando. He also won the Antonio Camuñas Prize for Architecture.

Contents

- Becoming an Architect

- Early Career and Art

- Paradores Hotels

- Parador de Guadalupe: Zurbarán

- Parador de Jaén: Castillo de Santa Catalina

- Parador de Arcos de la Frontera: Casa del Corregidor

- Hostería de Pedraza: Hostería Pintor Zuloaga

- Parador de Alcañiz: La Concordia

- Parador de Carmona: Alcazar del Rey Don Pedro

- Parador de Sigüenza: Castillo de Sigüenza

- Other Parador Projects

- Picardo's Paradores: A Look Back

- Other Restoration Projects

- Fundación Juan March Headquarters

- Royal Andalusian School of Equestrian Art

- Guernica at the Museo Nacional del Prado

- Royal Academy of Fine Arts

- Antonio Camuñas Prize

- Personal Life

- Images for kids

- See also

Becoming an Architect

José Luis Picardo was born in Jerez de la Frontera, Spain, on June 18, 1919. His father passed away when José Luis was ten years old. He then moved to Madrid with his mother and brothers.

He first wanted to join the navy. But the military schools in Madrid were closed at the time. So, he started studying law. However, the Spanish Civil War began in July 1936, when he was just 17. This stopped his law studies.

Studying Architecture

To avoid leaving Madrid during the Civil War, Picardo joined the office of architect Luis Moya Blanco. Moya Blanco was a professor at the Escuela Técnica Superior de Arquitectura de Madrid. He was very impressed by Picardo's skills. Moya Blanco encouraged Picardo to stop studying law and become an architect instead.

After the Civil War and the government that followed, there were fewer architects in Spain. Some had left the country or could no longer work. In 1945, Picardo started studying at the Higher Technical School of Architecture of Madrid.

From the very beginning, Picardo's talent for painting and drawing, especially his mastery of perspective, stood out. Other architects noticed him and praised his work. While he was still a student, architects hired him to paint murals inside their buildings. They also hired him to create drawings and perspectives of their building plans.

Picardo painted his first professional mural in 1939, at age 20. It was for the Cine Fígaro (Figaro Cinema) in Madrid. Painting murals was his main way to earn money when he was young.

As a student, Picardo also started drawing for Spanish architectural magazines. His drawings were described as "increasingly sophisticated" and of "extraordinary quality." He also became very interested in old buildings, especially how to protect and restore them. He traveled a lot to study buildings in Spain and other countries. These trips made him very interested in Spain's historical and local building styles. He was known as an "outstanding" student.

Early Career and Art

Architect

After finishing his studies in 1951, Picardo worked with architect and historian Fernando Chueca Goitia. They worked on several projects to preserve and restore old buildings. Picardo was one of 24 architects who signed the ''Manifiesto de la Alhambra'' in 1952. This document looked to the Alhambra in Granada for ideas. It aimed to create a unique Spanish style of modern architecture. This idea influenced much of Picardo's work, especially his designs for Paradores.

In the 1950s, Picardo worked on his own architectural projects. He entered competitions and published plans for buildings that hadn't been built yet. In 1951, he designed a center for fishermen in Altea. It got a lot of attention but was never built. He also designed a small, simple hotel for the Costa del Sol.

He entered competitions for treasury buildings in Gerona and Las Palmas. He came in second place in both. In 1958, he designed a six-story apartment building in Madrid with his brother Carlos Picardo.

In the early 1960s, Picardo built some houses in the traditional Andalucían style. He also built modern apartment blocks in Madrid. He then started working for the Spanish Ministry of Information and Tourism. This led to his important work in the 1960s and 1970s. He designed many hotels for the state-owned Paradores de Turismo de España network.

Even early in his career, Picardo was known as an excellent draughtsman. He could quickly create sketches, perspectives, and detailed plans for his projects.

Artist

Besides his architectural work, Picardo continued to receive commissions for decorative murals. He was skilled in using colors and techniques like watercolor and oil. His murals could be seen in places like the Hotel de Los Cisnes in Jerez and several locations in Madrid. He was considered an "outstanding" muralist.

His drawings of buildings were also published in a popular textbook. He traveled around Spain, making detailed drawings of traditional architectural elements for the book. His architectural drawings were highly praised.

In 1959, Picardo designed a unique pack of playing cards for the Spanish fashion brand Loewe. He gave the card characters a personal touch. For example, the King of Hearts was Charlemagne. These cards are now sought after by collectors. He also designed a set of tall, slender wooden chess pieces in 1960.

Around 1960, the General Directorate of Architecture published a small book called Dibujos de José Luis Picardo (Drawings of José Luis Picardo). It featured over 60 of his drawings and cartoons.

Paradores Hotels

From the early 1960s to 1985, Picardo spent much of his career working on the state-run hotel chain, Paradores de Turismo de España. The Ministry of Information and Tourism, which managed the hotels, wanted to expand the Parador network quickly. Picardo's experience with historical restoration and his interest in old buildings made him a perfect fit.

Picardo started by restoring old, monumental buildings. Sometimes, he built new hotels next to ruined monuments. He made sure the new parts looked exactly like the original designs. His projects kept the ancient look of the buildings while adding modern luxury hotel features.

Many of Picardo's drawings for his Paradores projects still exist. They show his detailed plans, from entire hotels to small door handles. His drawings include "before-and-after" views and bird's-eye perspectives. They all show his incredible skill.

For nearly 20 years, Picardo completed eleven major reconstructions of historical buildings. He also built new structures that blended perfectly with the old ones. His work influenced other architects in Spain and Portugal. Picardo's Paradores are highly respected by other professionals and loved by guests. People enjoy the historical feel and charm of his designs.

Parador de Guadalupe: Zurbarán

In July 1963, Picardo was asked to turn two old buildings in Guadalupe, Spain, into a Parador. These buildings were the Hospital de San Juan Bautista and the Colegio de Infantes. They were near the important Monastery of Santa María de Guadalupe.

Picardo found the buildings in very bad condition. His job was to save their basic structures and restore them to their original Mudéjar style. He partly tore down the old parts and rebuilt them as they had originally looked. He used old Mudéjar building methods with lime, clay, and wood.

The Colegio de Infantes became the main hotel area. Picardo added a dining room and guest terraces facing the garden. He kept the central cloister intact. He left the lower arches open but closed the upper ones with glass and wooden latticework. The exposed wooden beams and coffered ceilings were preserved.

The Hospital de San Juan Bautista was remodeled for the hotel's kitchens, laundry, and staff rooms. Picardo also designed a large breakfast room. He added chimneys with Arabic tiles for ventilation.

Picardo designed most of the furniture and interior decorations. He used many decorative wall tiles made by ceramicist Juan Manuel Arroyo Ruiz de Luna. These tiles often explained the history of the buildings. Picardo often worked with Arroyo on his Parador projects.

The restoration began in November 1963. The hotel, with 20 double rooms, opened on December 11, 1965. In 1981, Picardo added a new wing of guest rooms, increasing the total to 41.

Parador de Jaén: Castillo de Santa Catalina

At the same time, Picardo was asked to design a Parador at the Castillo de Santa Catalina in Jaén. The castle was built in the mid-13th century and was completely abandoned when Picardo arrived. It stands on a steep hill 800 meters above the city, offering amazing views.

Picardo started work in early 1963. He planned the building on the site of the castle's old barracks, not inside the castle itself. He wanted large windows so guests could enjoy the views.

He designed the new building to match the old castle's style and dimensions. The Parador opened on September 11, 1965. The first part had 7 double guest rooms with fireplaces and wooden balconies. It also had a cafeteria, bar, reception, lounge, and restaurant.

Picardo's Parador at Jaén looked like an old castle. The main structure was modern concrete and steel. But he covered it completely with stone, brick, wood, and iron. This made it look ancient. For example, the 20-meter-high vault in the lounge looks like it's made entirely of brick. But it hides a modern support structure. The large stone arches in the dining room also hide steel frames.

In 1969, Picardo added more service rooms, allowing 12 more guest rooms to be created. In 1973, he added another extension in the same style. This brought the total number of rooms to 43. The building was officially named a Parador in 1978.

Picardo also designed the interior, including furniture, wall hangings, and light fittings. He used coats of arms from old buildings and hand-painted ceramic tiles by Juan Manuel Arroyo. These tiles decorated the building and told its history.

Picardo's work at Jaén and Guadalupe set a style for his future Parador projects. He refined it where needed and repeated it faithfully elsewhere.

Parador de Arcos de la Frontera: Casa del Corregidor

The Parador at Arcos de la Frontera is in the old town, on top of cliffs overlooking the Rio Guadalete. Picardo first visited the site in February 1964. He decided to keep the old building fronts facing the main square and the castle. The rest of the site, including an old slaughterhouse, would be torn down. He saved seven columns from an old patio to use in the new building.

Demolition work was finished by February 1965. Picardo started building in October 1964. He found a crack in the cliff from an earthquake in 1755. To solve this, he built a patio as a separate structure. This way, any future ground movement wouldn't affect the Parador.

Picardo designed the Parador to look like a typical Andalucían house. It had an entrance hall leading to an open patio with terraces supported by the reused columns. The dining room and sitting room offered wide views of the river.

He copied many Andalucían architectural features throughout the building. This included exposed pine wood joists in the ceilings and terracotta floors. Like in Guadalupe and Jaén, Picardo designed much of the interior furniture, lighting, and decorations. He also used his signature ceramic tiles for decoration and historical texts.

Picardo planned for 18 guest rooms. Initially, only 9 were built. Some faced the plaza, and others faced the cliff, with open wooden galleries like those at Jaén. The Parador opened on November 7, 1966. In 1974, Picardo returned to complete his original plan, adding more rooms and bringing the total to 18. The extension opened in 1979.

Hostería de Pedraza: Hostería Pintor Zuloaga

In 1965, Paradores asked Picardo to restore the old Casa de la Inquisición (House of the Inquisition) in Pedraza. This would be a hostería, meaning only a restaurant and bar, without guest rooms.

The three-story building was mostly in ruins. Picardo was free to renovate it as he wished, keeping the medieval and rural feel of the village. He improved the windows and added his signature open wooden gallery at the back.

Inside, Picardo followed the rustic style of the region's inns. He created a spacious lounge with a large fireplace. The bar and dining room were on the upper floors, opening onto the balcony-gallery. He designed the furniture, lighting, and decorations to match the local style.

The hostería, named "Pintor Zuloaga," opened on December 14, 1967. Picardo also suggested expanding the property to include guest rooms, but this project never happened. The Pedraza Hostería closed in 1992 due to economic reasons.

Parador de Alcañiz: La Concordia

In 1966, Picardo began converting the Palacio de los Comendadores at Alcañiz into a Parador. This palace was part of the Castillo de los Calatravos, a monastery-fortress built in 1179. The castle had fallen into disrepair but was declared a National Monument in 1925.

Picardo worked on the immense south wing of the palace. Space was limited, so he could only provide 12 guest rooms. He converted two large ground-floor rooms with barrel-vaulted ceilings into the reception area and the bar/cafeteria. He left the exposed masonry of the walls and ceilings in these rooms. The main dining room, on the first floor, was designed like a palace's great hall. It had a large fireplace and a coffered ceiling with timber beams.

The 12 guest rooms were on the second floor. Picardo designed them with raised areas in front of the high windows so guests could see out easily. The public corridors had imitation stone groin vaults, a design he used in Jaén.

Picardo planned the interior decoration to reflect the palace's history. The ground floor had a medieval military design, while the upper floors were more palatial. He designed much of the furniture, beds, tables, and light fittings. He used the emblem of the Order of Calatrava as a decorative motif. He also used his characteristic ceramic murals by Juan Manuel Arroyo, which explained the castle's history.

The Parador opened on May 18, 1968. In 1975, Picardo designed a new wing to double the number of guest rooms. This plan was used in 1998, bringing the total rooms to 38.

Parador de Carmona: Alcazar del Rey Don Pedro

In 1966, Picardo was asked to inspect ancient sites near Sevilla for a new Parador. He found the ruined castle of Carmona, the Alcázar del Rey Don Pedro. He was very excited about Carmona and started preparatory work in 1968.

The castle was originally Muslim and was restored in the 14th century. It was severely damaged by earthquakes in 1504 and 1755. Most of its connecting walls were in ruins.

Picardo chose the highest point of the castle area, the Plaza de Armas, for the Parador. The views from here were spectacular. He decided to build the hotel on the edge of the cliff, overlapping the original castle walls. This allowed for guest rooms within the sloping walls below the ground floor.

However, a deep crack from the 1504 earthquake was found where Picardo planned the southern wall. This caused delays and required special measures to stabilize the ground. Cement was injected, and a reinforced concrete slab was built to support the foundations.

Picardo designed a Hispanic-Arabic layout with two central patios. One was for the public area, and the other for services. The design aimed to look like the original fortress. Even though it was a new building, Picardo made sure it looked historic and traditional. The south and east walls had four floors, sloping outwards to allow for rooms inside. The entrance side had two floors.

Picardo's first plan was for 23 double rooms and 10 single rooms. Due to delays, the Ministry decided to expand the building before completion. This increased the total guest capacity from 56 to 102. Most rooms were on the southern side, with some below the entrance level and others on the upper floors. The top-floor rooms had Picardo's typical timber balconies.

The building's main structure was concrete, covered with stone and brickwork. The roof had clay tiles and decorative chimneys, similar to those at Guadalupe. Inside, Picardo used limestone columns, ceramic tiling, and brick. The floors were marble and terracotta.

As in his previous Paradores, Picardo controlled every detail of the interior decoration. He created a Hispanic-Arabic, palatial Mudéjar style. He used many coffered ceilings and star latticework in wood and stone. The public patio had semi-circular arches on slender pillars. The dining room had a medieval Gothic style with exposed wooden beams and pointed arches. Lights, furniture, door fittings, and mural tiles were all designed by Picardo.

The Carmona Parador was opened on March 30, 1976, by King Juan Carlos I and Queen Sofía.

After the opening, a large crack was found parallel to the south side of the building. Despite efforts to fix it, movement continued, especially in the rainy season. Picardo could not be involved in these structural problems after 1978 due to new government policies.

Despite these issues, the Carmona Parador remains very popular. It now has 9 double rooms, 51 twin rooms, and 3 single rooms, totaling 123 guests.

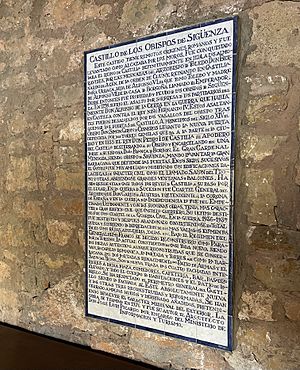

Parador de Sigüenza: Castillo de Sigüenza

In 1964, Picardo investigated old buildings in the Province of Guadalajara for a new Parador. He found the castle at Sigüenza to be the best option, even though it was completely ruined. It stood prominently above the town and cathedral.

The Castillo de los Obispos de Sigüenza was a palace-fortress with very old origins. It was changed many times between the 14th and 18th centuries. It then fell into disrepair and was badly damaged during the Spanish Civil War in 1937. It was left in ruins for over 30 years.

Picardo started analyzing the building in October 1969. He described the castle's condition as "pitiful." He decided to remodel it to look completely medieval, ignoring later additions. He wanted to recreate the castle's military feel with its towers and battlements. He also wanted to show as much bare stone as possible.

Work on converting the castle began in 1972. Picardo raised most of the outer walls by at least one story. This made the roofs flat and allowed for hotel rooms. The towers were also raised, including the twin towers of the fortified gateway, the barbican.

To make the castle look military, Picardo removed all large windows and balconies from the outer walls. He made the remaining exterior windows as small as possible. Damaged walls were rebuilt using the original stone. Plaster and rendering were removed to show the bare stone. All surrounding walls and towers were crenellated (had battlements).

Picardo cleared the central courtyard of all post-medieval additions. He wanted a "unity of style," focusing only on the medieval period. 40,000 tons of debris were removed from the courtyard.

Inside, Picardo used modern techniques like steel and concrete. But he hid them behind a fake historical look of stone, brick, timber, and iron. Since exterior windows were small, he added many windows to the courtyard walls to bring light inside.

On the north wall of the courtyard, Picardo built the main reception area. Above it were bedrooms with balconied terraces in his signature timber style. He copied the sgraffito decoration that had been on the castle's exterior onto the northern courtyard walls.

The bishops' throne room became the main guest lounge. It was a tall room with a timber-beamed ceiling and two large fireplaces. The dining room, on the east side, had the building's only large windows, looking out onto a wooded ravine. This room used Picardo's strong stone vaulting to hide the steel supports. A bar and café were next to the dining room. Wide wooden staircases led to the first and second-floor bedrooms. Some rooms were in the northeast tower, others faced south, and most looked into the courtyard. Upper-floor rooms had Picardo's typical balconies. Another lounge with a wooden coffered ceiling was on the first floor. Picardo also preserved the castle's oldest room, the original chapel.

A smaller, three-story monastic courtyard was built at the southern end of the castle, which had been heavily damaged. More guest rooms were arranged around it. On the inner face of the west wall, Picardo built a 65-meter-long banqueting hall with stone vaulting and a bar. Below this hall were large service areas.

Picardo, as usual, designed all the interior decor. He focused on a medieval style. He designed Castilian-style furniture, flooring, doors, windows, light fittings, and even heraldic displays. He built 38 guest rooms and one suite on the first floor, and 42 rooms and one suite on the second floor, for a total of 162 guests.

In the main entrance hall, Picardo placed a mural of 45 tiles. It told the history of the Castillo de los Obispos de Sigüenza and described the restoration work. He wrote that the "present building is almost all new," but that authentic parts like the Romanesque chapel and towers were preserved and reconstructed. He stated that the work was finished in 1976 and that he was the architect.

The Parador opened on July 20, 1976. It was officially opened by King Juan Carlos and Queen Sofía in April 1978. Sigüenza was Picardo's last major project for the Paradores.

The Parador was modernized in 1990, but Picardo's original style was carefully followed. Most improvements were just to update services and facilities. The Parador has kept its original character thanks to Picardo's design.

Other Parador Projects

In the 1960s and 1970s, Picardo also investigated other old buildings for possible Parador conversions. He drew up plans for several of these, but they either didn't become Paradores during his career or were completed by other architects.

Some of his advanced plans included the renovation of the castle at Puebla de Alcocer in 1969. He also worked on converting the 11th-century castle remains in Monzón in 1970, but he decided it wasn't possible.

Picardo also made preliminary designs for three buildings that later became Paradores, though he wasn't involved in their completion. These were the old palace at Olite (1963), the Castillo de la Zuda at Tortosa (1969), and the castle at Cardona (1970).

He also surveyed many other buildings that never became Paradores.

Picardo's Paradores: A Look Back

In the 1960s and 1970s, it was common in Spain to restore castles and convents without much archeological research. Picardo's projects were based on his own historical and architectural studies. Today, some historians and archeologists see this as controversial. They regret that large parts of old buildings were demolished without detailed investigation. Picardo's work at Sigüenza, for example, has been called "medieval scenery for tourist accommodation."

Dr. María José Rodríguez Pérez, a leading researcher, has studied Picardo's work. She says the architects aimed for "convincing set design" to bring back historical eras, usually the medieval period, for tourists. She described new extensions that looked identical to old monuments, like Picardo's Parador at Jaén, as "false history."

However, Picardo's early mentor, Fernando Choeca Goitia, called him "an architect who understands architecture as art." Picardo himself believed that "Art is eternal." He felt that if his reconstructions were art, they were justified. He had no problem using modern building techniques and hiding them with traditional materials, as long as the buildings looked old. One professor noted that Picardo would use hidden steel structures to support impressive vaults, or concrete slabs for coffered ceilings. Picardo believed that "In Art everything is possible."

Despite current historical views, Picardo's Paradores, especially those at Jaén, Carmona, and Sigüenza, are still among the most popular hotels in the network. One travel writer praised Jaén, saying, "I love this parador, so dramatic in its setting, so theatrically conceived... Inside, the deception is masterly, creating an ambience as old and austere as it is surrealistic and extravagant."

Other Restoration Projects

Picardo also worked on restoring other historical buildings. He restored parts of the Cádiz Cathedral, which was damaged by salt from the sea. He also worked on the Monastery of Saint Mary of Guadalupe and the Sigüenza Cathedral, which was damaged during the Civil War.

He rehabilitated the Palacio del Marqués de Montana in Jerez and rebuilt the Palacio de Gamazo in Madrid. His last project in 1995 was on the Archivo Histórico Provincial de Salamanca in Salamanca.

Fundación Juan March Headquarters

In 1970, Picardo was invited to compete to design a new headquarters for the Fundación Juan March in Madrid. This foundation promotes Spanish culture and science. Juan March himself was impressed by Picardo's work at the Parador in Jaén.

In 1971, Picardo won the competition. He said he found inspiration in buildings from Greece and New York. He aimed for "the classic perfection of the Parthenon and the constructive audacity of the new languages of New York."

Picardo designed a building of "extreme simplicity and elegance, of great architectural beauty and modernity." The building, started in 1972, had seven floors above ground and four below. Picardo put most of the building underground to create a large garden. It was designed as a cube with continuous horizontal bands of dark anodised aluminium windows and white Carrara marble cladding. Black and white were the main colors.

For the interior, Picardo designed several assembly halls, auditoriums for concerts and conferences, exhibition spaces, libraries, and offices. The main materials inside were white marble, bronze, and walnut.

Picardo included art and sculptures in the building. Artists like Eduardo Chillida and Pablo Serrano created pieces specifically for it. Picardo also designed the large bronze double doors leading to the garden. The 1,700-square-meter garden was also designed by Picardo.

The building opened in January 1975 to great praise. One observer said Picardo "controlled proportions and spaces with complete ease." They called it "one of the best buildings in the recent history of Madrid." Picardo himself considered it his best work.

Royal Andalusian School of Equestrian Art

In 1978, Picardo was asked to build a large indoor riding arena for the Real Escuela Andaluza del Arte Equestre in Jerez de la Frontera, his hometown. This school works to preserve the heritage of the Pura Raza Española.

Picardo's task was to design a sala de equitación, a huge arena for horse shows. It needed to seat up to 1,600 spectators. It also needed stable facilities for 60 horses.

Picardo used a neo-Renaissance style with colors that represented Andalucía. The outside was a deep ochre color, like the region's soil. The walls were stark white, like traditional Andalucían homes. Rows of relief pillars supported the large hip roof. There were 54 large circular windows around the building and 36 dormer windows in the roof for ventilation.

Inside, the display area was rectangular with six tiers of seating. Picardo repeated the exterior colors inside. The arena had ochre sand, and the walls and ceiling were bright white. At one end was the royal box. At the other was the grand entrance leading to the stables and a central octagonal tack room. Five stable blocks radiated from the tack room, each with 12 horse stalls.

The Sal de Equitación opened for performances in 1980.

Guernica at the Museo Nacional del Prado

When Pablo Picasso's famous 1937 anti-war painting Guernica came to Spain in 1981, it was decided to display it permanently at the Museo Nacional del Prado in Madrid. Picardo and architect José García María de Paredes were asked to design a way to display the painting safely.

The painting needed to be protected by armored glass from bombs, bullets, and vandalism. The challenge was that the painting was very large (7.76 meters long by 3.49 meters high). But the largest available armored glass sheets were smaller. So, they decided to place the painting some distance behind the main glass sheet. This way, the metal frame of the glass wouldn't block the view.

They built an armored glass and steel polyhedron case. Its bevels (slanted edges) met the floor, walls, and ceiling for full security. The main glass was tilted at 10 degrees to avoid reflections. The lights were placed inside the case. The large room allowed the entire painting to be seen from 25 meters away.

Guernica was installed in September 1981. The room opened to the public on October 25, Picasso's 100th birthday. Within a year, over a million people had seen Guernica in its new setting. Some people loved the display method, calling it "magnificent." Others were not so convinced.

In 1992, Guernica was moved to a new gallery at the Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía. The display designed by Picardo and García de Paredes is no longer used.

Royal Academy of Fine Arts

On February 3, 1997, at age 78, Picardo was elected a member of the Real Academia de Bellas Artes de San Fernando (Royal Academy of Fine Arts of San Fernando). He gave a speech called Hipólito when he joined the Academy on February 22, 1998. In his speech, he talked about two of his passions: architecture and horses. He said, "The horse is an animal that surpasses the human body in beauty, strength and speed." He added that "architecture, in turn, is the art that protects this human body." He couldn't decide which was more beautiful because both "are perfections."

In 2000, Picardo gave the academy his oil painting Guardia civil en el puerto de Alazores. It shows five policemen on horses. The academy also has a portrait of Picardo painted in 1953.

Antonio Camuñas Prize

In 2001, Picardo won the important Premio Antonio Camuñas de Arquitectura (Antonio Camuñas Prize for Architecture). This prize is given every two years to a Spanish architect who has excelled in architectural renovation. The jury praised Picardo as an architect "knowledgeable about our culture." They noted that he "quietly exercised his professional activity, reinterpreting and valuing the richness of our historical heritage."

Personal Life

José Luis Picardo married Trinidad de Ribera Talavera. They had five children: three boys and two girls.

A US travel journalist described Picardo in 1972 as "a package of energy, wit and imagination... eyes twinkling."

Picardo passed away on July 27, 2010, in Madrid.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: José Luis Picardo Castellón para niños

In Spanish: José Luis Picardo Castellón para niños

| Leon Lynch |

| Milton P. Webster |

| Ferdinand Smith |