Atlantic salmon facts for kids

The Atlantic salmon, Salmo salar, is a type of fish that belongs to the Salmonidae family. These amazing fish live in the northern Atlantic Ocean and in rivers that flow into it. They have also been successfully moved to the north Pacific Ocean.

People sometimes call Atlantic salmon by other names like bay salmon, black salmon, or silver salmon. Some Atlantic salmon never go to the sea; they are called landlocked salmon. This can happen because of human actions or natural disasters.

Contents

What Do Atlantic Salmon Look Like?

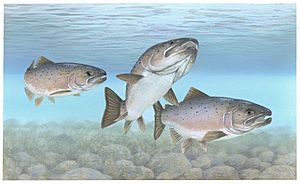

Atlantic salmon are the biggest fish in their group, Salmo. After living in the sea for two years, they usually grow to be about 71 to 76 centimeters (28 to 30 inches) long. They can weigh between 3.6 to 5.4 kilograms (8 to 12 pounds). But some salmon that spend four or more winters in the sea can get much bigger! The heaviest Atlantic salmon ever caught weighed about 49.44 kg (109 pounds) in Scotland in 1960. The longest one, caught in Norway in 1925, was about 160.65 cm (63 inches) long.

Young Atlantic salmon look different from adults. When they live in fresh water, they have blue and red spots. As they grow up, they turn a shiny silver-blue. You can usually tell an adult Atlantic salmon by the black spots mostly above its lateral line (a line along its side that helps it sense things). The tail fin usually doesn't have spots. When it's time to reproduce, male salmon might get a slight green or red color. Salmon have a sleek, torpedo-shaped body and strong teeth. All their fins, except for one called the adipose fin, have black edges.

Where Do Atlantic Salmon Live?

Atlantic salmon live in places where the water temperature is just right for them. Because of climate change, some southern groups of these fish, like those in Spain, are getting smaller. Scientists think they might disappear from those areas soon.

Originally, Atlantic salmon laid their eggs in rivers in Europe and on the eastern coast of North America. When Europeans came to North America, they brought salmon eggs to the rivers on the west coast. They also tried to bring them to other places like New Zealand. However, most of these attempts didn't work well in New Zealand because there weren't the right ocean currents. Still, there is at least one group of landlocked Atlantic salmon in New Zealand that never goes to the sea.

Young salmon stay in the river where they were born for one to four years. When they are big enough (around 15 cm or 6 inches), they go through a change called smoltification. Their camouflage changes from spots that help them hide in streams to shiny sides that help them in the sea. Their bodies also change to handle the difference between fresh water and salty ocean water. After this change, the young fish, now called smolts, start swimming with the river current instead of against it.

When smolts reach the sea, they follow ocean currents. They eat tiny sea creatures called plankton or young fish like herring. While in the sea, they can feel the Earth's magnetic field, which helps them navigate.

After a year of good growth, they use sea currents to travel back to the river where they were born. It's a common idea that salmon swim thousands of kilometers, but they mostly "surf" on ocean currents. They find their home river by smell; only about 5% of Atlantic salmon go up the wrong river. So, Atlantic salmon live in their birth river and the ocean currents that connect to it in a big circle.

Sadly, many wild salmon disappeared from rivers during the 1900s. This was due to too much fishing and changes to their homes. By the year 2000, the number of Atlantic salmon was very low.

What Do Atlantic Salmon Eat?

Young salmon start eating just a few days after hatching. Once they use up the food in their yolk sac (like a built-in lunchbox), they begin to hunt. Baby salmon eat tiny creatures without backbones. As they get bigger, they might sometimes eat small fish. They hunt both on the river bottom and in the current. Some have even been seen eating salmon eggs! Their favorite foods include caddisflies, blackflies, mayflies, and stoneflies.

As adults, Atlantic salmon eat much larger food. This includes Arctic squid, sand eels, amphipods, Arctic shrimp, and sometimes herring. Eating these bigger foods helps them grow much larger.

How Do Atlantic Salmon Behave?

Young salmon, called fry and parr, are thought to be territorial, meaning they might try to protect their space. However, it's not fully clear if they truly guard territories. While they might sometimes act aggressively towards each other, their social order isn't well understood. Many salmon have been seen swimming together in groups, especially when they leave the river for the ocean.

Adult Atlantic salmon are considered more aggressive than other types of salmon. They are more likely to attack other fish. This is a problem in places where they have become an invasive species. They can attack native salmon like Chinook salmon and coho salmon.

Life Cycle of the Atlantic Salmon

Most Atlantic salmon follow a pattern called anadromous migration. This means they do most of their feeding and growing in salty ocean water. However, adult salmon return to spawn (lay eggs) in the freshwater streams where they were born. The eggs hatch there, and the young fish grow through several stages.

Atlantic salmon don't actually need saltwater to live. There are many groups of them that live their entire lives in freshwater, especially in the Northern Hemisphere. For example, there used to be a group in Lake Ontario that lived its whole life cycle in the lake's waters. In North America, these landlocked salmon are often called ouananiche.

Freshwater Stages

The freshwater part of an Atlantic salmon's life can last from two to eight years, depending on where the river is located. Young salmon in southern rivers, like those near the English Channel, might leave for the sea after just one year. But those further north, like in Scottish rivers, can be over four years old. In northern Quebec, some smolts (young salmon ready for the sea) have been found to be eight years old! The average age they leave depends on how long the water temperature stays above 7°C (45°F).

The first stage is the alevin stage. At this point, the fish stay in the breeding ground and use the food stored in their yolk sacs. During this time, their gills develop, and they become active hunters. Next is the fry stage. The fish grow and leave the breeding ground to find food. They move to areas where there are more prey. The last freshwater stage is when they become parr. In this stage, they get ready for their long trip to the Atlantic Ocean.

During these freshwater stages, young Atlantic salmon can easily be eaten by other animals. Nearly 40% of them are eaten by trout alone! Other predators include different fish and birds. Whether eggs and young salmon survive depends a lot on the quality of their habitat, as Atlantic salmon are sensitive to changes in their environment.

Saltwater Stages

When parr turn into smolt, they begin their journey to the ocean. This usually happens between March and June. As they travel, they get used to the changing saltiness of the water. Once they are ready, young smolts leave, often preferring to go out on an ebb tide (when the water is flowing out).

After leaving their home streams, they grow very quickly during the one to four years they live in the ocean. Atlantic salmon typically travel from their home streams to an area near West Greenland. During this time, they face dangers from humans, seals, Greenland sharks, skate, cod, and halibut. Some dolphins have been seen playing with dead salmon, but it's not clear if they eat them.

Once they are big enough, Atlantic salmon enter the grilse phase. This is when they are ready to return to the same freshwater stream they left as smolts. After returning to their home streams, the salmon stop eating completely before laying their eggs. Scientists believe that the smell of their home stream plays a very important role in how salmon find their way back. Once a fish weighs more than about 250 grams (0.55 pounds), birds and many fish no longer prey on them. However, grey and common seals often eat Atlantic salmon. The chance of a salmon surviving to this stage is estimated to be between 14% and 53%.

Reproduction

Atlantic salmon lay their eggs in rivers in Western Europe, from northern Portugal up to Norway, Iceland, and Greenland. They also breed on the east coast of North America, from Connecticut in the United States north to northern Labrador and Arctic Canada.

The female salmon builds a nest called a "redd" in the gravel at the bottom of a stream. She uses her tail to create a strong current of water, digging a hollow in the gravel. After she and a male fish release their eggs and milt (sperm) upstream of the hollow, the female uses her tail again. This time, she moves gravel to cover the eggs and milt that have settled in the hollow.

Unlike many Pacific salmon species that die after laying their eggs, Atlantic salmon can reproduce more than once. This means they can recover and return to the sea to repeat their journey and lay eggs again, sometimes several times. However, migrating and laying eggs takes a huge toll on their bodies, so most salmon only spawn once or twice. Atlantic salmon show a lot of variety in when they become adults. They might mature as parr, or after one to five winters in the sea. This variety helps them survive changes in river flows. For example, if there's a drought year, some fish of a certain age might not return to spawn, saving themselves for other, wetter years.

Related pages

Images for kids

-

A Fish ladder built to help Atlantic salmon and Sea-trout get over a weir.

-

Seine fishing for salmon – by Wenzel Hollar, 1607–1677.

-

Atlantic salmon marine cages in the Faroe Islands.

-

A fishmonger in Lysekil, Sweden shows a Norwegian salmon.

See also

In Spanish: Salmón del Atlántico para niños

In Spanish: Salmón del Atlántico para niños