Licancabur facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Licancabur |

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Highest point | |

| Elevation | 5,916 m (19,409 ft) |

| Geography | |

| Location | Chile / Bolivia |

| Parent range | Andes |

| Geology | |

| Age of rock | Holocene |

| Mountain type | Stratovolcano |

| Last eruption | Unknown |

| Climbing | |

| First ascent | Inca, pre-Columbian |

| Easiest route | Hike |

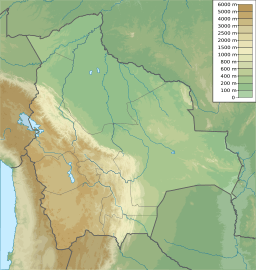

Licancabur is a tall stratovolcano (a cone-shaped volcano) located right on the border between Bolivia and Chile. It stands south of the Sairecabur volcano and west of Juriques. This impressive mountain is part of the Andes mountain range.

Licancabur has a very noticeable cone that reaches about 5,916 meters (19,409 feet) high. At its very top, there's a large crater about 400 meters (1,312 feet) wide. Inside this crater is Licancabur Lake, one of the highest lakes in the world! The volcano has three layers of old lava flows coming down its sides.

Licancabur formed on top of older rocks from the Pleistocene era. It has been active during the Holocene period, which means after the last ice age. We don't know of any eruptions in recent history. However, some lava flows that reached Laguna Verde are about 13,240 years old. The volcano mainly erupted a type of rock called andesite, with smaller amounts of dacite and basaltic andesite.

The weather around Licancabur is cold, dry, and very sunny. It gets a lot of ultraviolet radiation from the sun. Licancabur doesn't have any glaciers. Closer to the bottom of the volcano, you can find cushion plants and shrubs. In the past, chinchillas were hunted on the volcano's slopes.

Licancabur is a holy mountain for the Atacameno people. They see it as a relative of Cerro Quimal mountain in northern Chile. Many archeological sites have been found on its slopes and even inside its summit crater. This crater might have been an ancient watchtower.

Contents

The Name of Licancabur

The name "Licancabur" comes from the Kunza language, spoken by the Atacameño people. In their language, "lican" means "people" or "village," and "cábur" means "mountain." So, Licancabur means "mountain of the people." It's also sometimes called "Volcan de Atacama" or "Licancaur." The border between Bolivia and Chile, set by a treaty in 1904, actually goes right across the volcano.

Licancabur's Location and Formation

Where Licancabur Stands

Licancabur is part of the Central Volcanic Zone, which is a long chain of volcanoes in the Andes. It sits on the western edge of a high plateau called the Altiplano. Other active volcanoes nearby include Putana, Llullaillaco, and Lascar.

Licancabur is a very symmetrical cone, standing 5,916 meters (19,409 feet) tall. It rises about 1,500 meters (4,921 feet) above the land around it. The base of the volcano is about 9 kilometers (5.6 miles) wide. The sides of the cone are quite steep, about 30 degrees.

The volcano has erupted many lava flows. Some of the younger lava flows on the western side are about 6 kilometers (3.7 miles) long. Older flows can stretch up to 15 kilometers (9.3 miles). Some very old lava flows even reached Laguna Verde. There are also deposits from pyroclastic flows (fast-moving hot gas and ash) that are about 12 kilometers (7.5 miles) long.

The Crater and Lake

At the very top of Licancabur, there is a large crater about 400 meters (1,312 feet) wide. Inside this crater is an oval-shaped lake. The lake is about 90 meters (295 feet) below the crater's edge. It's about 85 meters (280 feet) long and 1.5 to 3 meters (5 to 10 feet) deep.

This lake is fed by snowfall and is one of the highest lakes in the world. In 1955, scientists thought the lake might have spilled over a low point in the crater rim when the climate was wetter. Now, extra water probably seeps out, which keeps the lake from getting too salty. There are other lakes like this in the Andes at similar high altitudes.

Nearby Volcanoes

Licancabur is just south of Sairecabur, which is a group of volcanoes. To the east of Licancabur is its partner volcano, Juriques. It's about 5,710 meters (18,734 feet) high and has a large crater about 1.5 kilometers (0.93 miles) deep. Volcanoes like Licancabur and Juriques often line up from west to east in this area because of how the Earth's plates move.

What Licancabur is Made Of

Licancabur has mostly erupted a type of rock called andesite. But scientists have also found basaltic andesite and dacite rocks. These rocks are usually dark and grey. The older lavas tend to have basaltic andesite, while the newer ones have dacite.

Scientists study the tiny crystals inside these rocks to learn about the volcano. The temperature of the magma (melted rock) before it erupted helped decide what kind of rocks would form. For dacite, the magma was about 930°C (1,706°F). For andesite, it was between 860°C and 1060°C (1,580°F and 1,940°F).

Scientists believe the magma for Licancabur formed deep underground. It came from the melting of the Earth's oceanic crust as it slid beneath the South American continent. This melted rock then mixed with other melted rock from the Earth's mantle.

Climate and Wildlife Around Licancabur

The area around Licancabur has been very dry for a long time. It gets a lot of sunshine all year because of a high-pressure system in the atmosphere. Since there's not much moisture, the strong winds help to spread the sun's energy. Winds usually come from the west, but in summer, they can change direction.

Because of its location near the equator and its high altitude, Licancabur receives a huge amount of ultraviolet radiation (UV). In fact, some reports say it has the highest UV levels in the world!

Temperatures at the crater lake can range from 5°C (41°F) down to -40°C (-40°F). In 1955, observers noted that temperatures at the summit were always below freezing.

Licancabur gets about 360 millimeters (14 inches) of rain each year, mostly as snow. Snow from storms usually melts within a few days. However, in sheltered spots, snow can last for months.

Licancabur is part of the Eduardo Avaroa Andean Fauna National Reserve. The plants at lower altitudes are typical of a high desert. You can find cushion plants and tussock grass at higher elevations. In some wetter areas, like river valleys, you might see thorny shrubs. However, the surrounding Atacama Desert has very little plant life.

At higher altitudes, melted snow helps support more life on Licancabur than on other similar mountains. You can find chinchillas, grasses, tola bushes, butterflies, flies, and lizards even at very high elevations. In the past, a type of tree called Polylepis incana might have been more common here when it was wetter.

Licancabur's Eruptive History

Licancabur was built up in three main stages, all involving lava flows. The last stage also included deposits from explosive eruptions. Most of the volcano's cone was formed during the second stage. The oldest lava flows are on the western and northern sides of the volcano. They are partly covered by newer flows from Licancabur and from the nearby Sairecabur volcano.

Licancabur mostly formed after the last major ice age, between 12,000 and 10,000 years ago. Its youngest lava flows are on its sides. These flows were not affected by glaciers, and some still have their original shapes. Lava flows that reached Laguna Verde have been dated to about 13,240 years ago.

The volcano has not erupted in recorded history. The condition of ancient Inca ruins on the mountain suggests that there haven't been any eruptions in the last thousand years. The crater lake of Licancabur has warm water (about 14°C or 57°F) and sometimes bubbles. This suggests that heat from inside the Earth might be keeping the lake from freezing. If Licancabur were to become active again, it would most likely erupt lava and pyroclastic flows from its crater or sides.

Humans and Licancabur

Even though Licancabur is not the tallest mountain nearby, it stands out and is very well-known. The Atacameno people considered it a holy mountain and worshipped it. Other high mountains are also seen as sacred. Licancabur was thought to be divine, and people were sometimes stopped from climbing it. It was believed that climbing it would bring bad luck. For example, the 1953 Antofagasta earthquake was seen as punishment for someone trying to climb the mountain that year.

Licancabur is considered the "mate" (partner) of Quimal mountain. During the solstices, these mountains cast shadows over each other. A legend says that a legless Inca king lived on Licancabur's summit. He was carried around, and sometimes his carriers died and were buried with treasures. Another story tells of Incas hiding gold and silver in the crater lake. The treasures supposedly disappeared, making the lake bitter and emerald-green. Licancabur is seen as a "male" mountain of fire, unlike San Pedro, which is a "mountain of water."

Ancient people offered golden objects, like a guanaco (a type of llama), as tributes in the summit crater. Between 1,500 and 1,000 years ago, people buried in San Pedro de Atacama were placed facing the volcano. Even the Pukará de Quitor fortress in Chile is built to face Licancabur.

In 1953, climbers found three buildings on Licancabur. They were built using the pirca style, where stones fit together without mortar. There was also a woodpile between two of the buildings. A special ceremonial platform is located at the very top of Licancabur.

Because of its amazing views, which include the city of Calama and old travel routes, Licancabur might have been a watchtower for the Atacamenos. This watchtower might have worked with other fortresses in the area. An ancient settlement found near Licancabur had a central courtyard surrounded by buildings. The pottery found there is similar to that from other important sites. An Inca rest stop, called a tambo, was also reported at the volcano. Its construction shows how much the Inca civilization influenced this region.

Other ancient sites have been found on Andean mountains like Acamarachi and Pular. These sites had stone structures and firewood. Many were used during the Inca period.

The Atacameno people first settled the area around Licancabur, probably because of the water in the local canyons. Later, the Incas arrived, followed by the Spanish in the early 1500s. Both groups were looking for resources like yareta (a type of plant) and chinchillas.

Climbing Licancabur

Climbing Licancabur is quite challenging, unlike some nearby mountains. Its upper part is very steep, and the ground is loose and prone to landslides. Earthquakes, snow, wind, or heat from the volcano can make the ground unstable.

Ascending from the Bolivian side usually takes about six hours to go up and half that time to come down. You need to be careful during winter, but the mountain can be climbed any month of the year. In 1953, a road was built that went up to about 4,267 meters (14,000 feet). The first recorded climb of the volcano was in 1884 by Severo Titicocha. Landmines have been reported on the Chilean side of the mountain, so climbers must be very cautious.

See also

In Spanish: Volcán Licancabur para niños

In Spanish: Volcán Licancabur para niños

- List of volcanoes in Bolivia

- List of volcanoes in Chile

- List of Andean peaks with known pre-Columbian ascents

| Aurelia Browder |

| Nannie Helen Burroughs |

| Michelle Alexander |