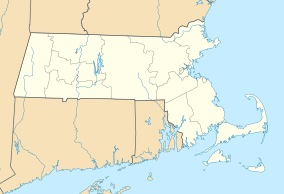

Longfellow House–Washington's Headquarters National Historic Site facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Longfellow House–Washington's Headquarters National Historic Site |

|

|---|---|

The Longfellow House

|

|

| Location | Cambridge, Massachusetts, USA |

| Area | 2 acres (0.81 ha) |

| Established | October 9, 1972 |

| Visitors | 50,784 (in 2015) |

| Governing body | National Park Service |

| Website | Longfellow House-Washington's Headquarters National Historic Site |

The Longfellow House–Washington's Headquarters National Historic Site is a special place in Cambridge, Massachusetts. It's famous for two big reasons. First, it was the home of Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, a very well-known American poet, for nearly 50 years. Second, before Longfellow lived there, it was the headquarters for General George Washington during the early days of the American Revolutionary War.

The house was built in 1759 for a man named John Vassall Jr.. He owned a large farm in Jamaica. Vassall had to leave the area when the American Revolutionary War began because he supported the King of England. George Washington then moved into the house on July 16, 1775. He used it as his main base during the Siege of Boston until April 4, 1776.

Later, Andrew Craigie, who was a chief pharmacist for Washington's army, bought the house in 1791. He added some parts to it. After Craigie died, his wife, Elizabeth, rented out rooms to help pay her bills. One of her renters was Henry Wadsworth Longfellow. Longfellow eventually became the owner in 1843 when his father-in-law bought it for him as a wedding gift. He lived there until he passed away in 1882.

The Longfellow family was the last family to live in the house. In 1913, they created a special group called the Longfellow Trust to keep the house safe. In 1972, the house and all its furniture were given to the National Park Service. Today, you can visit it during certain times of the year. It's a great example of the Georgian architecture style from the mid-1700s.

Contents

History of the House

Building the House

The house was first built in 1759 for John Vassall Jr. He was a Loyalist, meaning he was loyal to the King of England during the American Revolution. Vassall inherited the land when he was 21. He tore down an older building and built this new mansion. It was his summer home with his wife and children until 1774. Vassall also had several enslaved people working on his property.

In September 1774, just before the American Revolutionary War, Vassall's house and other properties were taken by the Patriots. This happened because he was seen as loyal to the King. He then left for Boston and later moved to England.

Washington's Headquarters

After Vassall left, the house was used as a temporary hospital after the Battles of Lexington and Concord. In June 1775, soldiers from the Marblehead, Massachusetts Regiment stayed there. General George Washington, who was the leader of the new Continental Army, needed more space for his team. So, he moved into the Vassall House on July 16, 1775. He used it as his headquarters and home until April 4, 1776.

During the Siege of Boston, Washington found the view of the Charles River from the house very helpful. Many important people visited Washington at the house. These included John Adams and Abigail Adams, Henry Knox, and Nathanael Greene. It was also in this house that Washington received a poem from Phillis Wheatley, the first African-American poet to have her work published.

Martha Washington, George Washington's wife, joined him in December 1775. She stayed until March 1776. She brought family members with her. In January 1776, the Washingtons celebrated their wedding anniversary in the house. Mrs. Washington wrote to a friend that they often heard "cannon and shells from Boston and Bunkers Hill." She used the front living room as her own reception area. The Washingtons also had several servants, including enslaved people like "Billy" Lee. They often hosted guests and bought a lot of food and drinks.

Washington left the house in April 1776. After him, a wealthy merchant named Nathaniel Tracy owned the house for a few years. Then, another merchant, Thomas Russell, owned it until 1791.

The Craigie Family and Renters

Andrew Craigie, who was the first chief pharmacist for the American army, bought the house in 1791. He even hosted Prince Edward, Duke of Kent and Strathearn, who was the father of Queen Victoria, in the house's ballroom. Craigie married Elizabeth, who was 17 years younger than him.

Craigie spent a lot of money trying to fix up the house. When he died in 1819, Elizabeth was left with many debts. To support herself, she started renting out rooms. Many of her renters were connected to nearby Harvard University.

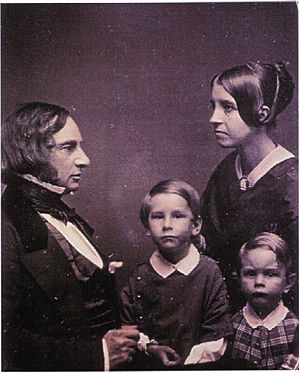

Henry Wadsworth Longfellow moved to Cambridge to work as a professor at Harvard. He rented rooms on the second floor of the house starting in the summer of 1837. Elizabeth Craigie first thought he was a student and didn't want to rent to him. But Longfellow convinced her he was a professor and the author of a book she was reading.

Longfellow's landlady, Elizabeth Craigie, was known for being a bit unusual. Longfellow once wrote about how canker-worms were eating the elm trees on the property. Elizabeth would let them crawl on her turban and refused to protect the trees. She said, "Why, sir, they have as good a right to live as we—they are our fellow worms." Longfellow loved his new rooms, which were the same ones George Washington had used. He wrote to a friend, "I live in a great house which looks like an Italian villa: have two large rooms opening into each other. They were once Gen. Washington's chambers."

Longfellow wrote some of his first important works in this house. These included Hyperion and Voices of the Night, which had the famous poem "A Psalm of Life". These early years in the house were the real start of Longfellow's writing career. Elizabeth Craigie died in 1841.

The Longfellow Family Home

After Elizabeth Craigie died, Longfellow continued to rent part of the house. In 1843, Nathan Appleton, Longfellow's father-in-law, bought the house for $10,000. He gave it to Longfellow as a wedding gift when Longfellow married his daughter Frances. Longfellow's friend reminded them what a special gift it was, "where Washington dwelt in every room." Longfellow was proud of the connection to Washington. He even bought a statue of Washington in 1844.

Longfellow lived in the house for the next 40 years. He wrote many of his most famous poems there, like "Paul Revere's Ride" and "The Village Blacksmith". He also wrote longer stories such as Evangeline, The Song of Hiawatha, and The Courtship of Miles Standish. In total, he published 11 poetry books, two novels, three epic poems, and several plays while living in this house. He also translated Dante Alighieri's Divine Comedy. He and his wife often called it "Craigie House" or "Craigie Castle."

Longfellow created a beautiful garden, and his wife decorated the inside of the house. They added central heating in 1850 and gaslights in 1853. The family welcomed many artists, writers, politicians, and other famous people. Visitors included Charles Dickens, William Makepeace Thackeray, and singer Jenny Lind. In 1876, Emperor Dom Pedro II of Brazil also visited the house. The Longfellows raised their three daughters and two sons in the home.

Longfellow often wrote in his first-floor study, which used to be Washington's office. He was surrounded by pictures of his friends. He would write at a table, a desk, or in an armchair by the fireplace. His second wife, Fanny, sadly died in the home in July 1861. Her dress accidentally caught fire. Longfellow tried to put out the flames and saved her face from burning. However, he was badly burned on his own face and started growing a beard to hide the scars.

Preserving the Historic Site

Keeping History Alive

Longfellow died in 1882. His daughter, Alice, was the last of his children to live in the house. In 1913, the Longfellow children created the Longfellow House Trust. Their goal was to protect the house and its view of the Charles River. They wanted to keep the home as a memorial to both Longfellow and Washington. They also wanted to show it off as a great example of Georgian architecture.

The house became famous even while the poet was alive. Its picture often appeared with his writings and on postcards. Its fame grew even more after Longfellow's death.

In 1962, the trust successfully worked to have the house named a national historic landmark. In 1972, the Trust gave the property to the National Park Service. It then became the Longfellow National Historic Site and opened to the public as a museum. Visitors can see many of the original 19th-century furnishings, artwork, and over 10,000 books that Longfellow owned. Everything on display belonged to the Longfellow family. On December 22, 2010, the site was renamed Longfellow House–Washington's Headquarters National Historic Site. This was done to make sure people remembered its important connection to George Washington.

The site also has about 750,000 original documents about the people who lived in the home. These old papers are available for researchers to study by appointment.

Across the street from the Longfellow House is Longfellow Park. This park was kept undeveloped to make sure the house still had a clear view of the Charles River. In the middle of the park is a memorial dedicated in 1914. It has a statue of the poet and carvings of famous characters from his stories, like Miles Standish and Evangeline.

In 1994, local people started the Friends of the Longfellow House. This group helps raise money to support the site and its ongoing preservation projects.

What's in the Collection?

The National Park Service says the Longfellow House has a "rich and varied collection of artifacts and archival materials." This includes fine art, decorative items, furniture, books, clothing, toys, tools, and Asian art. These items help tell the story of the people who lived there.

Architecture and Gardens

House Design and Changes

The house built in 1759 was in the Georgian style. It had large columns on the front that framed the main entrance and two side wings. This design showed the wealth and importance of John Vassall's family. In 1791, Andrew Craigie added two side porches and a two-story back section. He also made the library bigger, turning it into a large ballroom with its own entrance.

During the Longfellow family's time, not many big changes were made to the structure. Frances Longfellow wrote that they had "no desire... to change a feature of the old countenance which Washington has rendered sacred."

The Beautiful Gardens

The Longfellow House is also known for its garden on the northeast side of the property. Henry Wadsworth Longfellow started creating the first garden, shaped like a lyre, soon after his wedding. In 1845, he began to improve the garden seriously. He imported trees from England with help from a scientist named Asa Gray. These trees included a cedar of Lebanon and pines from different parts of the world.

The lyre shape wasn't very practical, so a new design was made in 1847. This new design was a square around a circle, which was then divided into four tear-shaped garden beds. These beds were outlined by trimmed boxwood plants. Mrs. Longfellow called the shape a "Persian rug."

After her father died in 1882, Alice Longfellow asked two of America's first female landscape architects, Martha Brookes Hutcheson and Ellen Biddle Shipman, to redesign the garden. They created it in the Colonial Revival style. The garden was recently restored by the Friends of the Longfellow House. They finished the last part of its reconstruction, a historic pergola, in 2008.

Replicas of the House

For a while, Longfellow's home was one of the most photographed and recognized houses in the United States. In the early 1900s, a company called Sears, Roebuck and Company even sold smaller blueprints of the house. This meant anyone could build their own version of Longfellow's home.

Several copies of Longfellow's house exist across the United States. One replica, simply called Longfellow House, is in Minneapolis. It was originally built by a businessman named Robert "Fish" Jones. Today, it serves as an information center for the Minneapolis Park System.

A full-size copy of the house was built in Great Barrington, Massachusetts, around 1900. This building is the only remaining full-size replica that still looks like the original historic home. There is also a replica in Aberdeen, South Dakota.

See also

- Wadsworth-Longfellow House in Portland, Maine

- List of National Historic Landmarks in Massachusetts

- List of residences of American writers

- National Register of Historic Places listings in Cambridge, Massachusetts

- List of Washington's Headquarters during the Revolutionary War

| John T. Biggers |

| Thomas Blackshear |

| Mark Bradford |

| Beverly Buchanan |