Philip Melanchthon facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Philip Melanchthon

|

|

|---|---|

Portrait by Lucas Cranach the Elder, 1543

|

|

| Born |

Philipp Schwartzerdt

16 February 1497 |

| Died | 19 April 1560 (aged 63) Wittenberg, Electoral Saxony in the Holy Roman Empire

(now Germany) |

| Alma mater | |

| Years active | 16th century |

| Theological work | |

| Era | Reformation |

| Language | German |

| Tradition or movement | Lutheranism |

| Signature | |

Philip Melanchthon (born Philipp Schwartzerdt; 16 February 1497 – 19 April 1560) was an important German reformer. He worked closely with Martin Luther during the Protestant Reformation. Melanchthon was a key thinker and helped shape the Lutheran faith. He also played a big part in designing new education systems.

Melanchthon and Luther believed that people were saved by their faith in God, not just by good actions. They also thought that the church's rules about confession and forgiveness were too strict. They both disagreed with the idea that the bread and wine in the eucharist literally turned into Christ's body and blood. Instead, they believed Christ's body and blood were present with the bread and wine. Melanchthon taught that God's "law" shows us what is right. But the "gospel" (good news) shows us God's free gift of grace through faith in Jesus.

Contents

Early Life and Education

Philipp Schwartzerdt was born on 16 February 1497, in Bretten, Germany. His father, Georg Schwarzerdt, was a craftsman who made armor. His mother was Barbara Reuter. In 1689, his hometown was burned down by French soldiers. The Melanchthonhaus was built on the site of his birthplace in 1897.

In 1507, Philipp went to a Latin school in Pforzheim. There, he learned about Latin and Greek writers. He was greatly influenced by his great-uncle, Johann Reuchlin. Reuchlin was a Renaissance humanist, a scholar who loved classical learning. Reuchlin suggested that Philipp change his last name. "Schwartzerdt" means 'black earth' in German. So, Philipp changed it to "Melanchthon," which means the same in Greek.

In 1508, when Philipp was only eleven, both his grandfather and father died. He and his brother moved to Pforzheim to live with their grandmother.

The next year, he started studying at the University of Heidelberg. He studied philosophy, public speaking, and astronomy. He became known for his knowledge of Greek. In 1512, he was too young to get his master's degree. So, he went to Tübingen. There, he continued his studies and also learned about law, mathematics, and medicine.

After earning his master's degree in 1516, he began studying theology. He became convinced that true Christianity was different from the traditional teachings at the university. He also gave lectures on public speaking and classical authors. His first writings included poems, a preface for a book, and a Greek grammar book.

Professor at Wittenberg University

Melanchthon was not always supported as a reformer at Tübingen. But then, Martin Luther invited him to the University of Wittenberg. He became a professor of Greek there at just 21 years old. He spent his time studying the Scriptures, especially the writings of Paul. He also learned more about the new Evangelical ideas.

In 1519, he attended a debate in Leipzig. Even though he was just a spectator, he shared his thoughts. When his ideas were criticized, Melanchthon defended them. He based his arguments on the authority of the Bible.

After giving lectures on the Gospel of Matthew and the Epistle to the Romans, he earned a degree in theology. He then joined the theology faculty. On 25 November 1520, he married Katharina Krapp, whose father was the mayor of Wittenberg. They had four children: Anna, Philipp, Georg, and Magdalen.

Important Theological Works

In 1521, Melanchthon wrote a defense of Luther. He argued that Luther only rejected church practices that went against the Bible. While Luther was away at Wartburg Castle, Melanchthon faced challenges from other reformers.

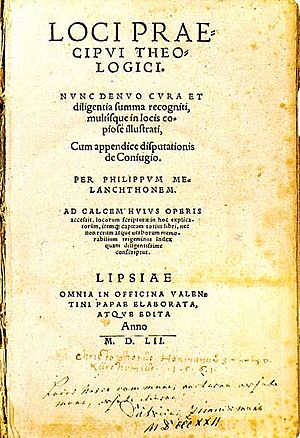

Melanchthon's book, Loci communes rerum theologicarum (1521), was very important for the Reformation. In it, he explained the new Christian teachings. This book helped create the Lutheran scholarly tradition. Later theologians built upon his work. Melanchthon also continued to lecture on classical subjects.

In 1524, Melanchthon traveled to his hometown. There, he met a representative of the Pope, Cardinal Lorenzo Campeggio. The Cardinal tried to convince him to leave Luther's side. In 1528, Melanchthon wrote a guide for pastors. It explained the evangelical teachings and rules for churches and schools.

In 1529, Melanchthon went with the elector to the Diet of Speyer. He hoped to convince the Holy Roman Empire to accept the Reformation. But his hopes were not met. He was initially friendly with the Swiss reformers. However, he later changed his mind. He called Huldrych Zwingli's view of the Lord's Supper "an unholy teaching."

The Augsburg Confession

The Augsburg Confession was presented at the Diet of Augsburg in 1530. This document became one of the most important texts of the Protestant Reformation. While it was based on Luther's ideas, Melanchthon wrote most of it. Luther was not completely happy with its calm tone. Some people criticized Melanchthon for not being firmer at the Diet. Others believed he was not meant to be a political leader.

After the Diet, Melanchthon focused on his academic work. His important theological work from this time was a commentary on the Epistle to the Romans (1532). In it, he explained that "to be justified" means "to be considered righteous." Melanchthon's growing fame led to invitations to other universities. But he chose to stay in Wittenberg.

Views on Mary

Melanchthon was careful about honoring saints. But he wrote positively about Mary, the mother of Jesus. He said that Mary's faith was an example for the church. He noted that Mary made mistakes, like asking for more wine at a wedding. But she accepted Jesus' gentle correction. He believed Mary was born with Original Sin like everyone else. However, she was spared its worst effects. He did not support the feast of the Immaculate Conception. He called it an invention. Melanchthon saw Mary as a symbol of the church. He believed that Christians should join her in suffering with Christ.

Views on Natural Philosophy

Melanchthon was interested in Greek mathematics, astronomy, and astrology. He believed that God had reasons for showing comets and eclipses. He published an edition of Ptolemy's Tetrabiblos in 1554. He thought that natural philosophy was linked to God's plan. This idea influenced how science was taught after the Reformation. From 1536 to 1539, he helped reform the University of Wittenberg. He also helped reorganize Tübingen and start the University of Leipzig.

Death and Legacy

Melanchthon died on 19 April 1560. A few days before, he wrote why he was not afraid of death. He wrote that he would be free from sins and see God. He also wrote that he would understand mysteries he couldn't grasp in life. He caught a severe cold in March 1560, which led to a fever. His body was already weak from many struggles.

In his final moments, he worried about the church. He prayed and listened to Bible passages. He found comfort in John 1:11-12. When his son-in-law asked if he wanted anything, he said, "Nothing but heaven." He was buried next to Luther in the Schloßkirche in Wittenberg.

The Lutheran Church–Missouri Synod remembers him on 16 February, his birthday. The Evangelical Lutheran Church in America remembers him on 25 June. This is the day the Augsburg Confession was presented.

His Work and Character

Melanchthon was very important for the Reformation. He organized Luther's ideas and explained them to others. He also made them the basis for religious education. Luther and Melanchthon worked well together. Luther inspired Melanchthon to work for the Reformation. Without Luther, Melanchthon might have been just another scholar. Luther spread the ideas among the people. Melanchthon, with his education, gained support from scholars. His calm nature and love of peace also helped the movement succeed.

Both men knew their roles were important. Melanchthon once wrote, "I would rather die than be separated from Luther." He even compared Luther to the prophet Elijah. When Luther died, Melanchthon said, "Dead is the horseman and chariot of Israel!"

Luther also praised Melanchthon. He called Melanchthon "a divine instrument." Luther, who often argued with others, never spoke against Melanchthon directly. Even when he was sad, Luther controlled his temper with Melanchthon.

Their differences came from their personalities and beliefs. They were different but also attracted to each other. Luther was more generous. He never criticized Melanchthon's personal character. However, Melanchthon sometimes lacked confidence in Luther.

As a Reformer

As a reformer, Melanchthon was known for being moderate and careful. He loved peace. Some people thought these qualities meant he lacked courage. But his actions often came from caring for the community. He wanted the church to grow peacefully. He was not afraid for himself. He just preferred to suffer with faith rather than act aggressively.

Another part of his character was his love for peace. He disliked arguments. But sometimes he was easily annoyed. His desire for peace often made him agree with others. He never forgot that his father asked his family "never to leave the church." He respected church history. This made it harder for him than for Luther to accept that they couldn't reunite with the Catholic Church. He valued the teachings of early church leaders.

He was conservative about church practices. He was even called "Crypto-Catholic" by some. But he never compromised on core beliefs for peace. He cared more about the church's structure than Luther did. He believed the church's power came from the whole community. He wanted to keep the traditional church structure, including bishops. He thought the government should protect religion and the church. He believed church courts should have both religious and non-religious judges. Melanchthon wanted church unity. But he didn't ignore differences in beliefs.

As he got older, he focused more on clear theological rules. He tried to ensure unity in beliefs through special formulas. These formulas were broad and focused on practical faith.

As a Scholar

Melanchthon was a great scholar of his time. He found simple ways to share his knowledge. His textbooks were used in schools for over a hundred years. He believed knowledge should serve moral and religious education. He helped prepare the way for the Reformation's religious ideas. He was a key figure in Christian humanism. This movement greatly influenced German academic life. His works were clear and useful. His writing style was natural and plain. He was better at writing in Latin and Greek than in German.

Melanchthon wrote many papers on education. He explained his ideas on how to learn. In his "Book of Visitation," he suggested schools teach only Latin. He divided children into three groups: those learning to read, those ready for grammar, and those skilled in grammar. He also thought the traditional "seven liberal arts" were not enough. He expanded the subjects to include history, geography, poetry, and new natural sciences.

As a Theologian

As a theologian, Melanchthon was good at organizing Luther's ideas. He made them easy to understand for teaching. He focused on practical matters. His main book, Loci, was written in short sections. The main difference between Luther and Melanchthon was Melanchthon's humanistic thinking. This made him open to connecting Christian truth with ancient philosophy.

Melanchthon's views were mostly similar to Luther's, with some small changes. He saw God's law as an unchanging spiritual order. He also believed that humans have some moral freedom. He said three things help people convert: God's Word, the Holy Spirit, and the human will. He defined freedom as "the ability to apply oneself to grace."

His definition of faith was less mystical than Luther's. He divided faith into knowledge, agreement, and trust. This led to the idea that understanding correct beliefs comes before personal faith. He also believed the Church was a group of people who followed true beliefs.

Melanchthon's ideas about the Lord's Supper were different from Luther's. He believed the physical elements and spiritual realities should be kept separate.

His beliefs changed over time, as seen in his Loci book. At first, he focused on evangelical ideas of salvation. Later editions became more like a textbook on beliefs. He eventually included the doctrine of God and the Trinity. He also said that free will helps in conversion. He emphasized the need for good works for moral discipline.

As a Moralist

In ethics, Melanchthon kept and updated ancient moral traditions. He explained the Protestant way of life. His books on morals were mostly based on classical writers like Cicero. His main works included Prolegomena to Cicero's De officiis (1525) and Epitome philosophiae moralis (1538).

In his Epitome philosophiae moralis, Melanchthon discussed how philosophy relates to God's law and the Gospel. He believed moral rules could be known through reason. He called these God's law and the law of nature. He thought that virtuous pagans did not understand Original Sin. So, they couldn't explain why people didn't always act virtuously. He believed sin darkened human reason. The revealed law, given because of sin, was just clearer than natural law. He believed that moral philosophy should be developed from natural principles. He did not make a sharp difference between natural and revealed morals.

His contributions to Christian ethics are found in the Augsburg Confession and his Loci. There, he described the Protestant ideal of life. This was about freely following God's law with faith and the Holy Spirit.

As an Interpreter of Scripture

Melanchthon's ideas on how to understand the Bible became the standard. He said that a good interpreter of the Bible must be a grammarian, a logician, and a witness. By "grammarian," he meant someone skilled in language, history, and ancient geography. He strongly believed in finding the single, literal meaning of the text. He said anything else was just applying the text to beliefs or life.

His commentaries were not just about grammar. They were full of theological and practical ideas. They confirmed Reformation doctrines and helped believers. Important commentaries include those on Genesis, Proverbs, Daniel, the Psalms, and especially the New Testament. He helped Luther translate the Bible. The books of the Maccabees in Luther's Bible are thought to be his work. A Latin Bible published in 1529 was a joint effort by Melanchthon and Luther.

As a Historian and Preacher

Melanchthon influenced how church history was studied. He was the first Protestant to try writing a history of Christian beliefs.

He also influenced how sermons were given. He never preached from a pulpit himself. His Latin sermons were for Hungarian students who didn't understand German. He also wrote a religious guide for younger students (1532) and a German catechism (1549).

Melanchthon also wrote the first Protestant guide on how to study theology. His influence helped advance every part of theology.

As a Professor and Philosopher

As a language expert and teacher, Melanchthon followed the ideas of South German Humanists. These scholars believed in the moral value of the humanities. For Melanchthon, the liberal arts and classical education led to understanding both natural and divine philosophy. He believed ancient classics were sources of pure knowledge. They were also the best way to educate young people. This was because of their beauty and moral content. Melanchthon organized educational institutions. He also created Latin and Greek grammar books and commentaries. He became the founder of learned schools in Protestant Germany. These schools combined humanistic and Christian ideals.

In philosophy, Melanchthon taught the entire German Protestant world. His philosophical books were influential for a long time.

He started with traditional university teachings. But as a passionate Humanist, he turned away from them. He came to Wittenberg planning to edit all of Aristotle's works. Under Luther's strong religious influence, his interest changed for a while. But in 1519, he edited Aristotle's Rhetoric and in 1520, his Dialectic.

He believed philosophy and theology were connected. Philosophy, like a light of nature, is born within us. It includes basic knowledge of God. But sin has made this knowledge unclear. So, God had to reveal his law again in the Ten Commandments. All law, including natural philosophy, only makes demands. The fulfillment of these demands is found only in the Gospel. The Gospel gives certainty in theology. It also confirms philosophical knowledge from experience and reason. Philosophy, as an interpreter of the law, is guided by revealed truth.

Besides Aristotle's Rhetoric and Dialectic, he published other works. These included De dialecta libri iv (1528) and Erotemata dialectices (1547).

Personal Appearance and Character

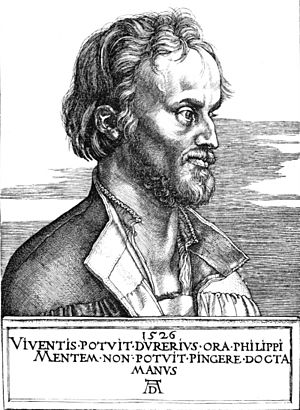

We have original portraits of Melanchthon by three famous painters. These include Hans Holbein the Younger, Albrecht Dürer, and Lucas Cranach the Elder. Melanchthon was small and physically weak. But he had bright, sparkling eyes that kept their color until he died.

He was never perfectly healthy. He managed to do so much work because he was very regular in his habits. He was also very moderate in what he ate and drank. He did not care much about money or possessions. He was so generous that his old servant sometimes had trouble managing the household. His home life was happy. He called his home "a little church of God." He always found peace there and cared deeply for his wife and children. Once, a French scholar found him rocking a cradle with one hand and holding a book in the other.

His kind nature also showed in his friendships. He said, "there is nothing sweeter nor lovelier than mutual intercourse with friends." His closest friend was Joachim Camerarius. Melanchthon called him "the half of his soul." He wrote many letters, which were not just a duty but a joy. His letters give us a good look into his life. He was more open in them than in public. He even wrote speeches and scientific papers for others, letting them use their own names. He was always ready to help his friends and everyone else.

He was very honest about himself. He admitted his faults even to his opponents. He was open to criticism from anyone. In his public life, he did not seek honor or fame. He truly wanted to serve the church and the truth. His humility came from his deep personal faith. He valued prayer, daily Bible reading, and attending church services.

See also

In Spanish: Felipe Melanchthon para niños

In Spanish: Felipe Melanchthon para niños

- Gottlob Frege, notable descendant of Melanchthon

- List of Erasmus's correspondents

- Dimitrije Ljubavić

- Philippists

- Ubiquitarians