Operation Elster facts for kids

Operation Elster was a secret mission by Nazi Germany during World War II. Its goal was to gather information about U.S. military and technology sites. "Elster" means "Magpie" in English.

The mission started in September 1944. Two German agents sailed from Kiel, Germany, on a submarine called U-1230. They landed in Maine, USA, on November 29, 1944. The agents were William Colepaugh, an American who had joined Germany, and Erich Gimpel, an experienced German spy.

They spent almost a month in New York City. They spent a lot of money on fun things but did not complete any of their mission goals. Colepaugh soon decided he didn't want to be a spy anymore. He turned himself in to the FBI and told them about Gimpel. This ended the operation in late December 1944.

In February 1945, a military court found both agents guilty of spying. They were first sentenced to death. After the war ended, President Harry S. Truman changed their sentence to life in prison. Gimpel was released in 1955, and Colepaugh in 1960.

Operation Elster was one of only two times Germany landed spies in the U.S. by submarine during the war. Some people thought the mission was to damage the Manhattan Project. However, official records show no proof of this.

Contents

What Was the Mission?

The idea to send spies to the United States came from Nazi Germany's foreign minister, Joachim von Ribbentrop. This specific mission was planned by the Schutzstaffel (SS), a powerful Nazi group. Operation Elster was Germany's second and last try to land agents on American soil using a submarine.

They had tried before with Operation Pastorius in June 1942. That mission also failed because one spy told the FBI everything. All eight agents involved were caught.

At first, Operation Magpie was meant to check how well Nazi messages were working in the U.S. Later, its goals grew. It also aimed to collect technical information, mostly from public sources. They were especially interested in shipyards, airplane factories, and rocket-testing sites.

The mission was supposed to last two years. The agents were meant to send information to Germany using morse code. They would build a shortwave radio transmitter for this. If they couldn't use the radio, they would send letters with secret ink. These letters would go to special "mail drops," including American prisoners of war or people in Spain. The Germans also hoped the agents would build more radios for future spies.

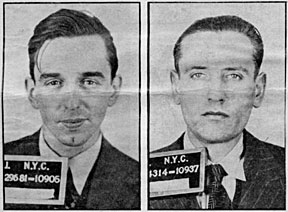

Who Were the Spies?

The two agents chosen for the mission were William Colepaugh and Erich Gimpel. Colepaugh was 26 years old and from Niantic, Connecticut. He was an American citizen who had joined Germany. Gimpel was 34 years old. He was a German radio operator and technician. He had been spying in other countries since the war began.

Gimpel was a very experienced spy. He started working as an informant in the mid-1930s in Lima, Peru. There, he worked for Telefunken as a radio engineer. He sent shipping information to German submarines waiting offshore. He also gathered useful information from corrupt Peruvian officials. He was sent back to Germany in 1942. Soon after, he was recruited by the German Foreign Intelligence Service. His skills as a spy and radio operator were very valuable.

Many stories say Colepaugh grew up in a family that liked Germany. They often listened to German radio messages. After high school, he briefly went to MIT. He also served in the United States Merchant Marine. In 1944, he feared being drafted into the Army. So, he joined a ship called the SS Gripsholm and sailed to Lisbon. There, he went to the German Embassy. He said he was giving up his U.S. citizenship and wanted to join the German Army. In Berlin, he was recruited by the Foreign Intelligence Service. They gave him lots of training in firearms and espionage.

The Germans didn't think Colepaugh was very reliable. But they needed him for the mission. He knew American society and customs well. It was also thought that Colepaugh would talk to local people for Gimpel. Gimpel spoke English with a strong German accent.

Landing in America

After finishing their training, Gimpel and Colepaugh got on the U-1230 submarine on September 22, 1944. They sailed towards the United States. Their landing spot was chosen because it was far away from people. It was near Crabtree Neck, Hancock Point, in Hancock, Maine. It was also one of the few places where the submarine could get close to the shore.

On the evening of November 29, 1944, the U-1230 entered Frenchman Bay. Gimpel and Colepaugh were put ashore around 11 p.m. Eastern Standard Time. They used an inflatable rubber raft rowed by two German sailors. Before going back to the submarine, the two sailors reportedly stood on American soil for a moment. They wanted to be able to brag about it later. The landing was delayed partly because the submarine had heard that another German submarine had been sunk nearby. After thinking about other landing spots, they decided to use the original one.

Gimpel and Colepaugh walked from the rocky beach to a local road. They hiked about 5 miles (8 km) to United States Route 1. Luckily, they were able to flag down a taxi going to Bangor. Two people saw the men walking in the Hancock Point area. Both noticed their city clothes, suitcases, and lack of hats on the snowy night. Mary Forni, a local housewife, saw them. Harvard Hodgkins, a 17-year-old Boy Scout, also saw them. He noticed their footprints in the snow came from a path leading to the beach. His father, a deputy sheriff, was away. By the time he returned and contacted the FBI, five days had passed.

What They Did in New York

From Bangor, the two spies traveled by train to Boston and then to New York City. They had fake identity papers. They also had about $60,000 in cash (a lot of money back then!). They had a secret stash of 99 diamonds, two .32 caliber Colt pistols, and a Leica camera for copying documents. They also had secret inks, special watches, and tiny hidden messages called microdots. These microdots contained radio plans and schedules.

Using fake names, Edward Green (Gimpel) and William Caldwell (Colepaugh), they rented an apartment. It was on the top floor of a building at 39 Beekman Place. They chose it because it didn't have a steel frame, which might block radio signals. They started buying parts for the radio transmitter Gimpel was supposed to build. They had left a heavy magnifying unit from Berlin on the submarine. So, they bought a magnifying glass, but it wasn't strong enough to read the microdots. Gimpel bought a radio handbook and some tools. He also bought a used General Electric radio receiver. He planned to turn it into a shortwave radio transmitter. But there is no proof he ever finished it.

Once in America, Colepaugh was more interested in spending money than spying. Gimpel tried to get him to record shipping activity in New York harbor. He also asked him to help buy radio parts. But Colepaugh preferred to enjoy the city's many attractions. Gimpel was more focused on the mission. However, he also enjoyed New York City. They often ate at nice restaurants and visited nightclubs. They also went to theaters like the Roxy and Radio City Music Hall. Some guess they spent between $1,500 and $2,700 (which is like $27,000 to $49,000 today) in just one month. Most of this money went to bars, restaurants, clubs, shows, and clothes.

Gimpel spent his time reading newspapers, watching newsreels at the movies, and eating at fancy steak houses. On December 21, Colepaugh left Gimpel for good. He took about $48,000 of their money and got a room at the Hotel St. Moritz.

How They Were Caught

A few days later, Colepaugh was worried. He found an old school friend, Edmund Mulcahy. He told his friend he was part of a Nazi spy mission. He asked for advice on how to surrender to the authorities. Colepaugh hoped he would not be punished if he turned himself in. He also hoped to share information about the Nazi war effort and tell on Gimpel. After talking over Christmas, Mulcahy agreed to contact the FBI for Colepaugh. On December 26, FBI agents arrived at the Mulcahy family home. They took Colepaugh into custody after asking him some questions.

The FBI was already looking for the two German agents. A Canadian ship had sunk near the Maine coast, suggesting a German submarine was nearby. Also, local people like Mary Forni and Harvard Hodgkins had reported seeing suspicious men. The FBI questioned Colepaugh at the United States Courthouse in Foley Square in New York City. He gave them information that helped them find Gimpel. They learned that Gimpel, who could read Spanish, often visited a Times Square newsstand. He bought Peruvian newspapers there. Gimpel was arrested at that spot on December 30.

Being Questioned

The two spies stayed in custody at the Courthouse in Foley Square. They were questioned for about three weeks. A U.S. Navy Department report about their questioning said it gave useful information about German submarine operations.

The report said Colepaugh was "somewhat unstable." But he seemed to try to tell the truth. He was smart, very observant, and had a great memory for details. He was friendly and cooperative with the people questioning him. He always made sure to say if something was what he saw or what he heard from others. The questioners thought he was helpful because he hoped to avoid the death penalty.

Gimpel was described as "a very difficult subject for questioning." He was a professional German spy and knew how to keep secrets. He believed he would be sentenced to death and that nothing he did would change that. He was not truthful at times and only told them what he thought they already knew. His statements were not very helpful.

The FBI also looked into Gimpel and Colepaugh's backgrounds. In a report to President Franklin Roosevelt, J. Edgar Hoover noted that Colepaugh's mother claimed to be a cousin of the President and First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt. She said she had family proof. However, Roosevelt dismissed this, telling Hoover, "He is no relation of mine."

Their Court Case

Gimpel and Colepaugh were moved to Governors Island on January 18, 1945. They were to be tried by a military commission. Future Supreme Court Justice Tom C. Clark was chosen to lead the case. This was only the third time in U.S. history that a military court tried American citizens for spying. The first was in 1865 after the assassination of Abraham Lincoln. The second was in 1942, after German agents from Operation Pastorius were caught.

Gimpel's lawyers were Major Charles E. Reagin and Major John E. Haigney. Colepaugh was represented by Major Thayer Chapman and Major Robert B. Buckley. During the trial, Colepaugh's lawyers claimed he had a change of heart in Germany. They said he took the spy mission as a way to get back to the U.S. and turn himself in. But he couldn't easily get away from Gimpel, who was watching him. The prosecution argued that Colepaugh was often alone without Gimpel. They said he had many chances to turn himself in during the month since he arrived in Maine, but he didn't.

In February 1945, the military court found them guilty of spying. They were sentenced to death. But President Harry S. Truman later changed this to life in prison. Gimpel was released in 1955, and Colepaugh in 1960.

Were They Spying on Atomic Secrets?

Some people claim Gimpel had a secret mission to damage "heavy water" factories related to the Manhattan Project. This project was about building the atomic bomb. However, there is no proof of this in the official records. Some supporters claimed Gimpel's target was a heavy water research place at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. But no such large program existed there. Official files about Colepaugh and Gimpel do not support this claim.

Author David Kahn wrote that Gimpel's book, Spy for Germany, should be read with great care. He said it has many differences from Gimpel's FBI statement. The most important differences are the book's claims that he was told to find atomic secrets, that he partly succeeded, and that he sent a radio message to Germany. None of these claims are supported by his own statement, Colepaugh's statement, or later questioning of his German spy bosses. The atomic claim is specifically denied by Walter Schellenberg, who was the head of German military intelligence.

Claims About V-Weapons

During his questioning, Colepaugh claimed that German submarines were getting long-range rocket launchers. He said the U-1230 was followed by other submarines with these V-weapons. These weapons were supposedly meant to be launched at New York City and Washington D.C.. The U.S. took this threat seriously. But it never happened, and Colepaugh's claim was later proven false.

Books and Films About the Mission

Gimpel helped write a book about his experiences called Agent 146 in the mid-1950s. It was later published as Spy for Germany in Great Britain. A West German film with the same name was made in 1956. Author Robert Miller researched his own book about Operation Elster. He noticed many differences in Gimpel's very dramatic stories about his spying in the U.S. Miller said Gimpel's book "is filled with sensational contradictions and fantasies... when compared to the official FBI reports and trial records." Author David Kahn also compared Gimpel's book to official records. He found it had many mistakes and made-up stories.

What Happened Later

The place where the spies landed was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 2003.

See also

- Operation Pastorius

- National Register of Historic Places listings in Hancock County, Maine

| DeHart Hubbard |

| Wilma Rudolph |

| Jesse Owens |

| Jackie Joyner-Kersee |

| Major Taylor |