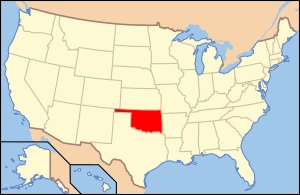

Paleontology in Oklahoma facts for kids

Paleontology in Oklahoma is all about studying ancient life, like fossils, found in the state of Oklahoma. Oklahoma is a super cool place for finding fossils! It has a huge collection of fossils from all three major eras of Earth's history when life was abundant: the Paleozoic, Mesozoic, and Cenozoic eras.

Oklahoma is especially famous for its Pennsylvanian fossils. This is because the rocks from that time are very complete here. Over millions of years, Oklahoma was sometimes covered by a warm, shallow sea and sometimes it was dry land. This means you can find fossils of sea creatures, early land animals, and even dinosaurs! The giant dinosaur Saurophaganax maximus is even Oklahoma's official state fossil.

Contents

Ancient Life in Oklahoma

Life in Ancient Seas

Oklahoma's fossil story begins in the Paleozoic Era. There are no fossils from the very oldest time, the Precambrian. For a long time, from the Cambrian to the Devonian periods, Oklahoma was covered by a warm sea.

- During the Cambrian Period, simple sea creatures like brachiopods (shellfish), graptolites (tiny colonial animals), sponges, and trilobites (ancient sea bugs) lived here.

- In the Ordovician Period, the seas were full of many types of brachiopods, bryozoans (moss animals), echinoderms (like sea stars), and tiny ostracods (shelled crustaceans). You can find lots of these fossils in places like Rock Crossing.

- The Silurian Period also had brachiopods, bryozoans, echinoderms, and sponges. A common trilobite called Calymene lived here too.

- By the Devonian Period, Oklahoma's seas were home to a huge variety of sea animals.

Life on Land and in Swamps

Later in the Paleozoic Era, during the Mississippian and Carboniferous periods, things started to change.

- In the Mississippian Period, Oklahoma still had sea creatures like Archimedes (a corkscrew-shaped bryozoan), brachiopods, and trilobites.

- During the Carboniferous Period, much of Oklahoma became dry land with huge river systems and swampy areas. These swamps were so big that they formed lots of coal deposits! Early four-legged animals, called tetrapods, walked through these swamps and left behind their footprints, which later turned into fossils.

- The Pennsylvanian Period (part of the Carboniferous) was a time when the sea sometimes covered the land again. Fossils from this period include various fish and the early tetrapods.

The sea slowly left Oklahoma by the end of the Paleozoic Era. The Permian Period in Oklahoma has one of the best fossil records of land animals in North America! You can find fossils of lungfish, different kinds of early amphibians, and early reptiles. There are also fossils of insects like beetles and millipedes. Sometimes, there's a gap in the fossil record called 'Olson's Gap,' where it's hard to find middle Permian fossils in North America.

The Age of Dinosaurs

For most of the Mesozoic Era, Oklahoma was dry land. This was the time of the dinosaurs!

- In the Late Triassic Period, small meat-eating dinosaurs left their footprints near Kenton. These tracks are called Grallator.

- During the Late Jurassic Period, huge plant-eating dinosaurs called sauropods lived here. Their fossils have been found in western Oklahoma.

- Most of Oklahoma was covered by a large inland sea called the Western Interior Seaway during the Cretaceous Period. This sea was home to giant ammonites (shelled squid-like creatures), echinoids (sea urchins), and many types of oysters. But even then, there were land animals too, including fish, amphibians, crocodiles, and even some dinosaurs and early mammals.

The Rise of Mammals

As the Rocky Mountains grew taller in the early Cenozoic Era, rivers flowed from them into Oklahoma. These rivers left behind sediments that preserved petrified wood and early mammal fossils.

- During the Pliocene Period, animals like camels, creodonts (ancient meat-eating mammals), and horses roamed the western part of Oklahoma.

- In the Pleistocene Epoch, also known as the Ice Age, Oklahoma was home to huge mammoths and mastodons. Their teeth and tusks are often found in gravel pits, and sometimes even full skeletons! Other Ice Age animals included Glyptotherium, a large, armored mammal related to the armadillo.

Discovering Oklahoma's Past

Scientific Research and Discoveries

Scientists have been studying Oklahoma's fossils for a long time.

- In 1931, a geologist named J. Willis Stovall from the University of Oklahoma heard that road workers found many fossils near Kenton.

- Stovall was very excited by what he saw. By 1935, he put together a team of students and workers to dig for fossils.

- His team worked for almost three years, digging through tons of rock! They found bones from many kinds of dinosaurs.

- They found fossils of Apatosaurus, Camarasaurus, Camptosaurus, and Stegosaurus.

- They also discovered a new type of meat-eating dinosaur that was later named Saurophaganax maximus, which is now Oklahoma's state fossil!

- Stovall's team also found fossils of a huge long-necked dinosaur called Diplodocus.

- Other discoveries included new types of crocodiles and turtles.

- Later, in 2004, scientists also found a bone from a Brachiosaurus among the fossils Stovall's team dug up.

Where to See Fossils

If you want to see some amazing fossils from Oklahoma, you can visit these museums:

Images for kids

-

A 1909 painting of a herd of Columbian mammoths, which lived in Oklahoma during the Ice Age.