Pan-Celticism facts for kids

Pan-Celticism is a movement that encourages friendship and teamwork among the Celtic nations and people. These nations are mostly in Northwestern Europe. Some groups want the Celtic nations to become separate countries and form their own union. Others just want them to work closely together. This includes nations like Brittany, Cornwall, Ireland, the Isle of Man, Scotland, and Wales.

The idea of Pan-Celticism grew from a time called Romantic nationalism and the Celtic Revival. It was most popular in the 1800s and early 1900s. Early connections happened through events like the Gorsedd and the Eisteddfod. The yearly Celtic Congress started in 1900. Today, the Celtic League is a main group for political Pan-Celticism. When people talk about cultural teamwork, like music or art festivals, they often use the term inter-Celtic.

Contents

What Does "Celtic" Mean?

There's been some discussion about the word "Celts." For example, the Celtic League once debated if Galicia in Spain should join. They decided no, because Galicia doesn't have a Celtic language spoken there today.

Some people in Austria believe they have Celtic roots. Austria is where the first known Celtic culture existed. After Austria was taken over by Nazi Germany in 1938, a writer interviewed Austrian scientist Erwin Schrödinger. He said, "I believe there is a deeper connection between us Austrians and the Celts." Today, Austrians are proud of their Celtic heritage. Austria also has one of Europe's largest collections of Celtic artifacts.

Groups like the Celtic Congress and the Celtic League define a "Celtic nation" as one that has a recent history of speaking a traditional Celtic language.

History of Pan-Celticism

How We Started Thinking About Celts Today

Long ago, before the Roman Empire and Christianity, people in Britain and Ireland spoke languages that led to today's Gaelic languages (like Irish, Scottish Gaelic, and Manx) and Brythonic languages (like Welsh, Breton, and Cornish). These people, and others in Europe who spoke similar languages that are now gone, are called "Celts." This idea became popular around the 1700s.

A Scottish scholar named George Buchanan was one of the first to connect these groups in the 1500s. He noticed that the languages of the Gauls (in France) and ancient Britons were similar. He thought if the Gauls were Celts, then the Britons were too. He also saw patterns in place names, suggesting they once spoke one Celtic language. These ideas became widely known later, thanks to scholars like Paul-Yves Pezron from Brittany and Edward Lhuyd from Wales in the early 1700s.

Over time, the Celtic peoples lost much of their independence. The Celtic Britons in Britain lost land to the Anglo-Saxons. Some fled to France and became the Breton people. The Gaels from Ireland expanded into Scotland. But then, the Normans arrived in the 11th century, causing problems for the Celts in Wales, Ireland, and Scotland.

Later, the British Empire and the Kingdom of France took more control. Even though the English and Scottish kings claimed Celtic ancestors, they pushed for everyone to become more English. In Ireland, the last Gaelic kingdoms were lost in 1607. The Statutes of Iona tried to make Highland Scots less Gaelic. These changes weakened the Celtic cultures.

Under British rule, Celtic-speaking people often became poor farmers and fishermen. The Industrial Revolution in the 1700s led to more people becoming English-speaking and moving away. Events like the Great Hunger in Ireland and the Highland Clearances in Scotland further reduced Gaelic speakers. In France, after the French Revolution, leaders wanted everyone to speak French. However, leaders like Napoleon were interested in the romantic idea of the Celts.

The Start of Pan-Celticism as a Political Idea

After a period of change in Britain and Ireland, a new interest in "the Celt" appeared in the late 1700s. This was part of the Celtic Revival. Key figures were James Macpherson, who wrote poems about Ossian, and Iolo Morganwg, who started the Gorsedd. English and Scottish poets were also inspired by Celtic ideas. People became fascinated by Druids and linked them to ancient stone structures like megaliths.

In the 1820s, early Pan-Celtic connections began, especially between the Welsh and Bretons. Scholars like Thomas Price and Jean-François Le Gonidec worked together on language projects. This led to a Pan-Celtic Congress in Wales in 1838, where Bretons attended. Among them was Théodore Hersart de La Villemarqué, who brought the Gorsedd idea to Brittany. Breton nationalists were very keen on Pan-Celticism, as it helped them connect with similar peoples outside France.

Around Europe, the study of Celtic languages and history grew as an academic field. German scholars like Franz Bopp and Johann Kaspar Zeuss led the way. Some scholars believed that if a nation lost its language, it would lose its identity. This idea was adopted by nationalists in Celtic nations, like Thomas Davis in Ireland, who wanted the Irish language to be strong again.

Charles de Gaulle (uncle of the famous General Charles de Gaulle) was a strong supporter of a Celtic Union in 1864. He believed that as long as a conquered people spoke their own language, they would remain free. He encouraged cooperation among Brittany, Ireland, Scotland, and Wales to protect their native languages. His friend Henri Gaidoz started a Pan-Celtic magazine called Revue Celtique in 1873.

In 1867, Charles de Gaulle organized the first Pan-Celtic meeting in Brittany. It was mostly attended by Welsh and Breton people.

Pan-Celtic Congresses and the Celtic Association

[[Multiple image|align=right|image1=2ndLordCastletown.jpg|width1=151|image2=Edmund Edward Fournier d'Albe (1868-1933).png|width2=157|footer=Lord Castletown and Edmund Edward Fournier d'Albe, who helped start the Celtic Association. They organized three Pan-Celtic Congresses in the early 1900s.}} The first big Pan-Celtic Congress was held in Dublin in 1901. It was organized by Edmund Edward Fournier d'Albe and Bernard FitzPatrick, 2nd Baron Castletown, through their Celtic Association. This followed a growing Pan-Celtic feeling at the National Eisteddfod of Wales in 1900. The Celtic Association also published a magazine called Celtia.

The Celtic Association held three Pan-Celtic Congresses: in Dublin (1901), Caernarfon (1904), and Edinburgh (1907). Each meeting started with a special ceremony involving a "Race Stone" called the Lia Cineil. This stone had letters from each Celtic nation's language carved into it. The ceremony was meant to show a strong Celtic identity against the British Empire's influence. It aimed to show that each Celtic people could have its own national space without losing its unique culture.

The reaction from Irish nationalists was mixed. Some, like D. P. Moran, made fun of the Pan-Celts, calling it a "farce." They didn't like the costumes and thought it was distracting from Irish goals. However, others, including Douglas Hyde and Patrick Pearse from the Gaelic League, attended the meetings. Lady Gregory even imagined an "Ireland-led Pan-Celtic Empire."

David Lloyd George, who later became the Prime Minister of the United Kingdom, gave a speech at the 1904 Celtic Congress.

Pan-Celticism After the Easter Rising

The Easter Rising in Ireland in 1916 greatly boosted Celtic nationalism. Irish revolutionaries fought against the British Empire to create an Irish Republic. They wanted to bring back Irish Gaelic culture and reduce English influence. This inspired groups in other Celtic nations, like Breiz Atao in Brittany and the Scots National League. Some also imagined a Celtic form of socialism.

However, the hope that an independent Ireland would help other Celtic nations gain freedom was not fully realized. The Irish Free State, once established, focused on diplomacy with Britain rather than supporting militant groups in other Celtic areas. Still, the Irish state, especially under Éamon de Valera, did support Celtic culture. For example, in 1947, de Valera visited the Isle of Man and arranged for recordings of the last native Manx Gaelic speakers.

Post-War Efforts and the Celtic League

After World War II, a group called "Aontacht na gCeilteach" (Celtic Unity) was formed in 1942 to promote Pan-Celticism. It aimed to be a meeting point for Irish, Scottish, Welsh, and Breton nationalists.

The renewed Irish republican movement during The Troubles also inspired other Celtic nationalists. In the 1960s and 1970s, there was new interest in Celtic culture. Some groups in Spain, like those in Galicia and Asturias, also became interested in Pan-Celticism. They attended festivals like the Festival Interceltique de Lorient. Although these regions had ancient Celtic roots, they no longer spoke Celtic languages. The Celtic League debated whether to include Galicia, but eventually decided that having a living Celtic language was key to being a Celtic nation.

21st Century Pan-Celticism

After the Brexit referendum in 2016, there were new calls for Pan-Celtic unity. Nicola Sturgeon, the First Minister of Scotland, spoke about a "Celtic Corridor" connecting Ireland and Scotland.

In 2019, Adam Price, the leader of the Welsh nationalist party Plaid Cymru, supported cooperation among Celtic nations after Brexit. He suggested a Celtic Development Bank for joint projects and a Celtic union. He also proposed that Wales and Ireland work together to promote their native languages.

Journalists and bloggers have also discussed ideas like a "Celtic confederation" or a "Celtic Council" for cooperation between Ireland, Scotland, Wales, and the Isle of Man.

In 2023, a 'Celtic Forum' was held in Brittany. Leaders from Wales, Scotland, Cornwall, Ireland, and Brittany attended. They discussed building on cultural and historical links and finding ways to work together on things like marine energy.

Arguments Against "Celt"

Since the late 1980s, some archaeologists have questioned the term "Celts." This idea, called "Celtoscepticism," suggests that the concept of Celts as a single group might not be historically accurate. These scholars often focus only on archaeological evidence and are wary of using the term "Celts" to describe ancient people in Britain or even the Celtic language family. They argue that the idea of a Celtic ethnic identity based on ancestry, culture, and language could be problematic.

However, many scholars, like John T. Koch, argue that the existence of a Celtic family of languages is a scientific fact that remains strong despite these debates.

Some archaeologists, like Malcolm Chapman and Simon James, wrote books questioning the idea of Celts. This led to heated discussions. Some believed that these anti-Celtic ideas were politically motivated, perhaps due to English nationalist feelings or worries about the decline of the British Empire, especially as Scotland and Wales gained more self-government. Others argued that their aim was to show the past as more "diverse" rather than a single Celtic identity.

Genetic studies suggest that the Celtic areas had major population changes. The last group, who spoke Celtic languages, arrived around 1000 BCE. This confirms that the Celtic languages came with a shift in population, not just people adopting a new language.

How Pan-Celticism Shows Up

Pan-Celticism can be seen in different ways:

Language Connections

Groups like the Gorsedd in Wales, Cornwall, and Brittany promote language ties. The Columba Initiative also connects Ireland and Scotland through language. There are two main groups of Celtic languages: the Goidelic languages (Irish, Scottish Gaelic, Manx) and the Brythonic languages (Welsh, Cornish, Breton).

Music Festivals

Music is a big part of Celtic cultural links. Inter-Celtic festivals are very popular. Some well-known ones are in Lorient, Ortigueira, Killarney, Kilkenny, Letterkenny, and Celtic Connections in Glasgow.

Sports

Wrestling

Celtic wrestling styles are very similar, suggesting they came from a common origin. In the Middle Ages, Irish and Cornish wrestlers often competed. The Irish style, Collar-and-elbow wrestling, uses a "jacket" like Cornish wrestling.

Cornwall and Brittany also have similar wrestling styles (Cornish wrestling and Gouren). They have had matches for centuries. Formal Inter-Celtic championships between Cornwall and Brittany started in 1928.

The Celtic wrestling championship began in 1985. Teams from Brittany, Cornwall, Ireland, Scotland, and other regions have competed.

Hurling and Shinty

Ireland and Scotland play each other in special international matches that combine hurling and shinty.

Handball

Irish handball and Welsh handball (Pêl-Law) share an ancient Celtic origin. Over time, they developed into separate sports. Informal matches likely happened in Wales in the 1800s between Irish immigrant workers and Welsh players.

Formal matches began after The Welsh Handball Association formed in 1987. They created new rules to allow international competition. The 1990s were a peak time for these matches, with Welsh champion Lee Davies winning a world title in 1997.

Rugby

Discussions about a Pan-Celtic rugby tournament happened for years. In 1999–2000, Scottish teams joined the Welsh Premier Division, creating the Welsh–Scottish League. In 2001, Irish teams joined, and it became the Celtic League.

Today, this tournament is called the United Rugby Championship. It has expanded to include teams from Italy and South Africa. However, the original "Celtic Rugby DAC" still runs the competition, keeping the inter-Celtic rivalries alive.

In Women's rugby union, the Irish, Welsh, and Scottish rugby unions started the Celtic Challenge competition in 2023. They hope to expand it in the future.

Political Cooperation

Political groups like the Celtic League, Plaid Cymru (Wales), and the Scottish National Party work together in the Parliament of the United Kingdom. Plaid Cymru has even raised questions about Cornwall and cooperates with Mebyon Kernow. The Regional Council of Brittany has formal cultural links with the Welsh Senedd. Political Pan-Celticism can range from a full union of independent Celtic states to occasional political visits.

During the Troubles in Northern Ireland, the Provisional IRA generally avoided attacks in Scotland and Wales. They saw England as the main colonial power.

In 2023, a 'Celtic Forum' took place in Brittany. Leaders from Wales, Scotland, Cornwall, Ireland, and Brittany attended. They discussed building on their cultural and historical links and finding ways to work together, for example, on marine energy.

Town Twinnings

Many towns in Wales and Brittany, and Ireland and Brittany, are "twinned." This means they have special friendships, with exchanges of local politicians, choirs, dancers, and school groups.

Historical Connections

The ancient kingdom of Dál Riata was a Gaelic kingdom that covered parts of western Scotland and northern Ireland. As late as the 1200s, Scottish leaders were proud of their Gaelic-Irish origins. In the 1300s, Scottish King Robert the Bruce said Ireland and Scotland shared a common identity. However, over time, their interests grew apart. The Scots becoming Protestant and Scotland's stronger political position compared to England were some reasons.

There was a lot of movement of people between Ireland and Scotland. Many Scottish Protestants settled in Ulster (Northern Ireland) in the 1600s. Later, in the 1800s, many Irish people moved to Scottish cities to escape the Irish famine. Recently, the study of Irish-Scottish connections has grown, with the Irish-Scottish Academic Initiative starting in 1995.

Organisations

- The International Celtic Congress is a non-political group that promotes Celtic languages in Ireland, Scotland, Brittany, Wales, the Isle of Man, and Cornwall.

- The Celtic League is a political Pan-Celtic organization.

Celtic Regions and Countries

Many Europeans have some Celtic ancestry. However, the main way to define a Celtic nation today is by having a living Celtic language. Based on this, the Celtic League and the Pan Celtic Congress (since 1904) consider these to be the Celtic nations:

Other regions with Celtic heritage include:

- Austria – Home to the ancient Hallstatt culture.

- Czech Republic – Home of the Boii tribe.

- England (parts like Cumbria and Devon)

- France – Known as Gaul in ancient times, with many Celtic tribes.

- Northern Italy – Once called Cisalpine Gaul, inhabited by Celtic people.

- Portugal – Home to tribes like the Lusitani.

- Spain – A large part of the Iberian peninsula was home to Celtic tribes. Some scholars believe the Celts originated here.

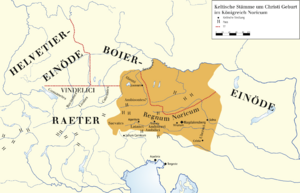

- Slovenia – Part of the ancient Celtic Kingdom of Noricum.

Celts Outside Europe

Areas with Celtic Language Speakers

There are groups of Irish and Scottish Gaelic speakers in Atlantic Canada.

The Patagonia region of Argentina has a large Welsh-speaking population. The Welsh settlement there, called Y Wladfa, started in 1865.

The Celtic Diaspora

Many people with Celtic roots live in the Americas, New Zealand, and Australia. They have many organizations, cultural festivals, and language classes. In the United States, Celtic Family Magazine shares news, art, and history about Celtic people.

Irish Gaelic games like Gaelic football and hurling are played worldwide. The Scottish game shinty is also growing in the United States.

Timeline of Pan-Celticism

Modern Pan-Celticism grew during a time of romantic nationalism in Europe, mostly before World War I. Some believe that later efforts came from a search for identity in a world with more industry and technology.

- 1820: The Royal Celtic Society was founded in Scotland.

- 1838: The first Celtic Congress (called Pan-Celtic Congress) was held in Abergavenny.

- 1867: The second Celtic Congress was held in Saint-Brieuc.

- 1888: The Pan-Celtic Society was formed in Dublin.

- 1891: The Pan-Celtic Society closed.

- 1919–1922: The Irish War of Independence led to most of Ireland becoming independent.

- 1939–1945: Second World War and German occupation of Brittany.

- 1947: The Celtic Union was formed.

- 1950: The Celtic Union ended.

- 1950: Cornwall hosted its first Celtic congress.

- 1961: The modern Celtic League was founded.

- 1971: The Killarney Pan Celtic Festival began.

- 1997: The Columba Initiative began.

- 1999: The Scottish Parliament and Welsh Assembly opened.

- 2000: The Cornish Constitutional Convention was formed.

- 2000–2001: The Cornish Constitutional Convention gathered over 50,000 signatures asking for a Cornish Assembly.

See also

- Agnes O'Farrelly

- Alan Heusaff

- Armes Prydein

- Charles de Gaulle

- John Stuart Stuart-Glennie

- Mona Douglas

- Richard Jenkin

- Ruaraidh Erskine

- Sophia Morrison

- Théodore Hersart de la Villemarqué

| Selma Burke |

| Pauline Powell Burns |

| Frederick J. Brown |

| Robert Blackburn |