Psychology of religion facts for kids

The psychology of religion looks at how people's minds and behaviors are connected to their religious beliefs and practices. It uses ideas and methods from psychology to understand different religions and how people experience them, whether they are religious or not.

Psychologists who study religion try to do three main things:

- They describe religious feelings, experiences, and how people show their faith.

- They try to explain where religion comes from, both in human history and in a person's life, considering many different influences.

- They look at the effects of religious beliefs and actions on individuals and on society.

This field of study really started in the late 1800s, but people have been thinking about these questions for centuries.

Contents

- What is the Psychology of Religion?

- History of the Field

- Ideas About Religion's Role

- Measuring Religion in Psychology

- How Religion Develops Over Time

- Evolutionary and Cognitive Psychology of Religion

- Religion and Prayer

- Religion and Ritual

- Religion and Personal Well-being

- Religion and Mental Health Challenges

- Religion and Therapy

- See also

What is the Psychology of Religion?

The main goals of the psychology of religion are:

- To clearly describe religious things, like shared traditions (such as rituals) or a person's own experiences and actions.

- To explain, using psychology, why these religious things appear in people's lives.

- To understand the results—both good and bad—of these religious experiences for individuals and for society.

One of the first challenges is to define "religion" itself. This word has changed its meaning a lot over time. Early psychologists knew this was tricky. Later, as psychology became more focused on numbers and measurements, researchers created many surveys to study religion, often based on Christian beliefs.

In recent years, especially among therapists, people have started using "spirituality" more often and trying to tell it apart from "religion." In some places, like the United States, "religion" can sometimes feel linked to strict rules or groups, which some people don't like. "Spirituality," on the other hand, is often seen as something very personal and about connecting with higher realities. Both words have changed their meanings over time in the West.

Researchers Schnitker and Emmons suggest that understanding religion as a search for meaning connects to three areas of psychology: what motivates us, how we think, and how we relate to others. Thinking about God and purpose is part of how we think. The need to feel in control is a motivation. And the search for meaning in religion is often tied to social groups.

History of the Field

William James

William James (1842–1910), an American psychologist and philosopher, is often called the founder of the psychology of religion. He wrote one of the first psychology textbooks. His book The Varieties of Religious Experience is a classic in the field, and his ideas are still important today.

James saw a difference between institutional religion (religious groups or organizations) and personal religion (an individual's own spiritual experiences). He was most interested in understanding personal religious experiences.

He also talked about two types of religiousness: healthy-minded and sick-souled. Healthy-minded people tend to focus on the good and ignore the bad in the world. Sick-souled people can't ignore suffering and need a powerful experience to make sense of good and evil.

James also believed in pragmatism when it came to religion. This means if religious actions and beliefs work for someone and help them, then they are a good choice for that person.

Other Early Thinkers

G. W. F. Hegel

Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel (1770–1831) thought that all systems of religion, philosophy, and social science are ways that our minds try to understand themselves and the world. He saw religion as a way humans record their experiences and thoughts. These writings, when collected, form the worldview of a religion.

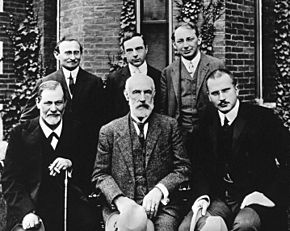

Sigmund Freud

Sigmund Freud (1856–1939) offered ideas about how religion began. In his book The Future of an Illusion, Freud suggested that religion is like a "fantasy" that people need to move past to grow up.

Freud believed that the idea of God is similar to a father figure. He thought that some religious beliefs could be like childhood ways of thinking. He felt that very strict religion could make people feel disconnected from themselves.

Carl Jung

The Swiss psychoanalyst Carl Jung (1875–1961) had a more positive view of religion and its symbols. He thought that psychologists couldn't answer whether God truly exists, so he remained neutral on that question.

Jung suggested that besides our personal unconscious (our hidden thoughts and feelings), there's also a collective unconscious. This is like a shared memory bank of human experiences, containing "archetypes" (basic, universal images that appear in all cultures). He believed that when these images come into our conscious mind, it can lead to religious experiences or artistic creativity.

Alfred Adler

Austrian psychiatrist Alfred Adler (1870–1937) focused on goals and motivation. One of his main ideas is that we try to make up for things we feel we are not good at. A lack of power often makes us feel less capable. Religion can fit into this because our beliefs in God often reflect our desire to be perfect or superior. For example, if God is seen as perfect, and we try to be perfect like God, we can feel better about our own imperfections.

Adler believed our ideas about God show how we see the world. He thought these ideas change over time as our view of the world changes. For instance, the old idea that humans were God's special creation is changing to the idea that we evolved through natural selection. This can lead to seeing God less as a real being and more as an idea representing nature's forces.

For Adler, it was important that the idea of God motivates people to act, and these actions have real effects on us and others. Our view of God guides our goals and how we interact with society.

Gordon Allport

In his 1950 book The Individual and His Religion, Gordon Allport (1897–1967) showed that people use religion in different ways. He talked about Mature religion and Immature religion. Mature religion is when someone's faith is flexible, open-minded, and can handle different ideas. Immature religion is more selfish and fits negative ideas about religion.

More recently, these ideas are called "intrinsic religion" (a true, heartfelt faith) and "extrinsic religion" (using religion for other reasons, like social status).

Erik H. Erikson

Erik Erikson (1902–1994) is famous for his theory of how people develop psychologically. He believed that religions are important for healthy personality development because they help cultures teach the good qualities needed at each stage of life. Religious rituals help with this development.

Erich Fromm

The American scholar Erich Fromm (1900–1980) built on Freud's ideas, offering a more detailed look at what religion does for people. Fromm thought that the right kind of religion could help a person reach their highest potential. However, he also felt that in practice, religion often becomes less healthy.

Fromm believed that humans need a steady way to understand the world, and religion often provides this. People look for answers to big questions that other sources can't provide, and religion seems to offer them. But for religion to be healthy, people must feel they have free will. A very controlling idea of religion can be harmful.

Rudolf Otto

Rudolf Otto (1869–1937) was a German scholar who studied different religions. His most famous book, The Idea of the Holy, talks about the idea of the "holy" as something mysterious and powerful. Otto called this feeling "numinous"—a non-rational, non-sensory experience that is outside of oneself. It's a mystery that is both fascinating and terrifying at the same time. This feeling of wonder is often at the heart of religious experiences.

Otto's ideas helped people study religion as a unique and important part of human experience.

Modern Thinkers

Many modern psychologists have written about the psychology of religion, especially in Europe and the US.

Allen Bergin

Allen Bergin is known for his 1980 paper that helped show that religious values do affect psychotherapy (a type of talk therapy). He was recognized for challenging traditional psychology by highlighting the importance of values and religion in therapy.

Robert A. Emmons

Robert A. Emmons wrote about "spiritual strivings" in his 1999 book, The Psychology of Ultimate Concerns. He suggested that spiritual goals help a person's personality become more whole.

Ralph W. Hood Jr.

Ralph W. Hood Jr. is a professor of psychology who has written many articles and books on the psychology of religion. He has also been an editor for several important journals in the field.

Kenneth Pargament

Kenneth Pargament is known for his book Psychology of Religion and Coping (1997). He studies how people use religion to deal with stress. He identified three ways people cope with stress using religion:

- Collaborative: People work with God to handle tough situations.

- Deferring: People leave everything up to God.

- Self-directed: People rely on themselves and don't involve God.

James Hillman

James Hillman, in his book Re-Visioning Psychology, suggested that instead of looking at religion through psychology, we should see psychology as a type of religious experience. He believed that all psychological events could be seen as effects of "Gods in the soul."

Julian Jaynes

Julian Jaynes, in his book The Origin of Consciousness in the Breakdown of the Bicameral Mind, had a unique idea. He suggested that religion might come from a time in human history before people had full consciousness. He thought that early humans might have heard voices that seemed to come from outside themselves (like from invisible gods or spirits), which helped them survive and organize their societies.

Ideas About Religion's Role

There are three main ideas about what role religion plays in the world today.

Secularization

The first idea, secularization, suggests that as science and technology advance, religion will become less important. This view supports separating religion from politics, ethics, and psychology. It also suggests that religious beliefs might lose their sense of the divine or the supernatural.

Religious Transformation

This idea challenges secularization. It suggests that as people become more individualistic, religion will change. Religious practices might become more personal and focused on spirituality. This could lead to more people seeking spiritual experiences, even outside traditional religious groups. Things like eclecticism (drawing from many spiritual systems) and New Age movements are examples of this.

Cultural Divide

This idea, put forward by Ronald Inglehart, suggests that religion helps people feel secure. So, in places like Europe where there's a lot of social and economic security, people might feel less need for religion. But in other parts of the world where there's less security, religion might remain very strong. This could lead to a growing difference in culture between these regions.

The idea that religiousness comes from a need for security is also supported by studies that see religious beliefs as a way to feel in control. People want to believe in order and structure to avoid feeling like things are chaotic. Studies have shown that when people feel less personal control, they are more likely to believe in external systems, like religion or government, that provide order.

Measuring Religion in Psychology

Since the 1960s, psychologists have used psychometrics (ways to measure psychological traits) to understand how people are religious. For example, the Religious Orientation Scale measures if someone's religion is "intrinsic" (deeply felt) or "extrinsic" (used for other reasons).

Newer surveys include the Age-Universal I-E Scale and the Religious Life Inventory, which measure different types of religious orientation. The Spiritual Experiences Index-Revised looks at spiritual maturity based on spiritual support and openness.

Religious Orientations and Dimensions

Some surveys look at different religious orientations, which are different reasons why someone might be religious (like intrinsic or extrinsic). Another approach is to list different dimensions of religion, which are different ways a person can show their religiousness. For example, Glock and Stark (1965) described five dimensions: what people believe (doctrinal), what they know (intellectual), how they act (ethical-consequential), what rituals they do, and their personal experiences.

Surveys for Religious Experience

Religious experiences can be very different. Some people describe supernatural events, while others talk about a feeling of peace or oneness. When we categorize religious experiences, we can think of them in two ways:

- Objectivist view: This idea suggests that a religious experience proves God's existence. However, some people question how reliable these experiences are as proof.

- Subjectivist view: This idea says that religious experiences don't necessarily prove God exists. Instead, the important thing is the experience itself and how it affects the person.

How Religion Develops Over Time

Many researchers have used stage models, like those from Jean Piaget (about thinking) and Lawrence Kohlberg (about morals), to explain how children develop ideas about God and religion.

James Fowler's Model

The most famous stage model for spiritual development is by James W. Fowler, a psychologist. He proposed six stages of faith development that happen throughout a person's life. These stages are similar to how thinking and moral development happen.

| No. | Fowler | Age | Piaget |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | Undifferentiated Faith |

0–2 years | Sensoric-motorical |

| 1 | Intuitive- Projective |

2–7 years | Pre-operational |

| 2 | Mythic- Literal |

7–12 years | Concrete operational |

| 3 | Synthetic- Conventional |

12+ years | Formal-operational |

| 4 | Individual-Reflective | 21+ years | |

| 5 | Conjunctive | 35+ years | |

| 6 | Universalizing | 45+ |

- Stage 0 – "Primal or Undifferentiated" faith (birth to 2 years): Babies learn if their environment is safe and caring. If they feel safe, they develop trust in the world and the divine. If not, they might develop distrust.

- Stage 1 – "Intuitive-Projective" faith (ages 3 to 7): Children learn about religion through experiences, stories, images, and the people around them. Their thoughts are very fluid.

- Stage 2 – "Mythic-Literal" faith (mostly school children): Children strongly believe in fairness and that their gods are often like humans. They often take metaphors and symbolic language literally.

- Stage 3 – "Synthetic-Conventional" faith (ages 12 to adulthood): Teenagers and young adults tend to follow authority and develop their religious identity. They might ignore conflicts in their beliefs to avoid feeling inconsistent.

- Stage 4 – "Individuative-Reflective" faith (mid-20s to late 30s): People take personal responsibility for their beliefs. They become open to more complex ideas about faith but also become more aware of conflicts in their beliefs.

- Stage 5 – "Conjunctive" faith (mid-life): People start to understand that reality is complex and that truth can't be explained by just one statement. They resolve conflicts by seeing a deeper, interconnected truth.

- Stage 6 – "Universalizing" faith (45+): People treat everyone with compassion, seeing them as part of a universal community. They live by universal principles of love and justice.

Fowler's model has led to a lot of research on how faith develops.

Other Ideas on Development

Some psychologists think that religious ideas come naturally to young children. For example, children might naturally believe that the mind can live on after the body dies. Also, children tend to see purpose and design in things, and they might prefer explanations that involve creation, even if their parents don't teach them that.

Researchers have also looked at how a child's early relationships might predict their religious conversion experiences. One idea is that children with secure relationships with their parents are more likely to have a gradual religious conversion, seeing God as a secure base. Another idea is that children with insecure relationships might have a sudden conversion, seeking a relationship with God to make up for their insecure attachments.

James Alcock suggests that several natural mental processes and biases combine to make believing in the supernatural seem automatic. These include magical thinking, seeing agents (like people or spirits) where there aren't any, and the idea that objects and events have a purpose.

Evolutionary and Cognitive Psychology of Religion

Evolutionary psychology suggests that our minds, like our bodies, have developed through natural selection to help us survive and reproduce. This means that certain ways of thinking might be common to all humans because they helped our ancestors.

Pascal Boyer is a key figure in the cognitive psychology of religion. He suggests that religious thinking and practices are a side effect of how our brains evolved. For example, our brains are good at understanding other people's minds, and this might lead us to imagine beings with thoughts and emotions, even if they don't have bodies (like gods). These ideas are striking and easy to remember.

People usually learn religious ideas and practices from their culture. A child raised in a Zen Buddhist family won't become an evangelical Christian without being exposed to that culture. Boyer believes that understanding these psychological processes can help us understand the nature of religious belief.

Steven Pinker thinks that the widespread human tendency to believe in religion is a scientific puzzle. He suggests that religious psychology might be a side effect of many parts of the mind that originally developed for other purposes.

Religion and Prayer

Prayer is a common religious practice. Many studies have looked at how prayer affects health. In the United States, about 55% of Americans say they pray daily. There are four main types of prayer:

- Meditative: Quiet thinking and spiritual reflection.

- Ritualistic: Reciting set prayers.

- Petitionary: Making requests to God.

- Colloquial: General conversation with God.

Studies have also found that prayer can involve awareness of oneself, reaching toward God, and reaching toward others.

Dein and Littlewood (2008) suggest that a person's prayer life can develop from immature to mature. A more mature individual might use prayer to ask for help coping with problems they can't change, and to feel closer to God or others, rather than trying to change reality. This change often happens during adolescence.

Prayer seems to have some health benefits. Studies suggest that reading and reciting Psalms can help people calm down. Prayer is also linked to happiness and religious satisfaction. Research has shown a negative link between prayer frequency and psychoticism (a personality trait linked to unusual thoughts). In Catholic students, frequent prayer was linked to higher neuroticism (a trait linked to anxiety). Some researchers suggest that physical actions during prayer, like bowing, might prepare a person for positive social behavior. Overall, small health benefits have been found consistently in studies.

There are different ideas about why prayer might have health benefits:

- Placebo effect: The belief that it will help, makes it help.

- Focus and attitude adjustment: Prayer helps people focus and have a more positive outlook.

- Activation of healing processes: Prayer might trigger the body's natural healing.

Other ideas include physiological (body), psychological (mind), social support, and spiritual factors. The spiritual factor goes beyond what science can currently measure, but it's included as a possible link between prayer and health.

Religion and Ritual

Another important religious practice is ritual. Religious rituals are actions and words performed in a specific way, based on tradition and culture.

Some suggest that rituals provide catharsis (emotional release) by creating distance from feelings. This allows people to experience emotions with less intensity. However, more recent ideas suggest that rituals help people connect with others, allowing for emotional expression.

Research also shows the social side of rituals. Performing rituals can show commitment to a group and might prevent people who aren't committed from getting group benefits. Rituals can also help emphasize moral values that guide a group and strengthen commitment to these values, helping society stay stable.

Religion and Personal Well-being

Religion and Health

There's a lot of research on the connection between religion and health. Thousands of studies have looked at how religion and health are related.

Psychologists think that religion can help both physical and mental health in several ways. It can encourage healthy lifestyles, provide social support, and promote a positive outlook. Prayer and meditation might also help the body function better. However, religion isn't the only source of health and well-being; not being religious can also have benefits.

Religion and Personality

Some studies have explored if there's a "religious personality." Research suggests that religious people tend to be more agreeable (kind and cooperative) and conscientious (careful and organized). People who identify as spiritual might be more extroverted (outgoing) and open to new experiences. However, people with very strict religious beliefs might be less open to new experiences.

Religion and Prejudice

Researchers have also looked at how religious beliefs can affect how people view others. Some studies show that stronger religious attitudes can predict negative attitudes toward people from different racial or social groups. This is often explained by intergroup bias, where religious people favor their own group and show disfavor toward other groups. This has been seen in many religious groups and shows how group dynamics play a role in religious identity.

Religion and Mental Health Challenges

While many researchers show that religion can have a positive role in health, others have found links between religious beliefs, practices, and experiences, and certain mental illnesses (like mood disorders or personality disorders).

In 2012, a team of experts from Harvard Medical School suggested a new category for mental health issues related to religious delusions or very intense religiousness. They compared the thoughts and behaviors of important figures in the Bible (like Abraham, Moses, Jesus Christ, and Paul) with patients who had symptoms of psychosis (like schizophrenia or manic depression). They suggested that these Biblical figures "may have had psychotic symptoms that contributed inspiration for their revelations," such as delusions of grandeur or hearing voices.

The research also looked at social models of mental health problems, studying new religious movements and charismatic cult leaders like David Koresh and Marshall Applewhite. They concluded that some people with psychotic symptoms can still form strong social groups, even if their view of reality is very distorted. This supports the idea that psychotic symptoms can exist on a wide range, from mild to severe, and are not always linked to an inability to function socially.

Religion and Therapy

Therapists are increasingly considering clients' religious beliefs to improve treatment. One approach is theistic psychotherapy, which uses religious principles in therapy. Therapists try to be respectful of clients' religious views while also using religious practices like prayer or forgiveness in therapy.

Pastoral Psychology

One way psychology of religion is used is in pastoral psychology. This field uses psychological findings to help pastors and other clergy provide better pastoral care to their congregations. It also helps chaplains in healthcare and the military. A main goal is to improve pastoral counseling. Some critics have argued that pastoral psychology in the mid-20th century moved too far away from traditional religious sources and became too focused on modern psychological ideas. More recently, pastoral psychology is seen as balancing both psychology and theology.

|

See also

In Spanish: Psicología de la religión para niños

In Spanish: Psicología de la religión para niños

| Roy Wilkins |

| John Lewis |

| Linda Carol Brown |