Reign of Juan Carlos I of Spain facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Kingdom of Spain

Reino de España

|

|||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1975–2014 | |||||||||||||

|

Motto: Plus ultra

Further beyond

|

|||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||

| Capital | Madrid | ||||||||||||

| Official languages | Spanish | ||||||||||||

| Recognised national languages | Languages of Spain | ||||||||||||

| Religion | Catholicism (until December 1978) Non-confessionalism (since December 1978) |

||||||||||||

| Demonym(s) | Spaniard | ||||||||||||

| Government | Francoist monarchy (until June 1977) Parliamentary monarchy (since June 1977) |

||||||||||||

|

• King

|

Juan Carlos I | ||||||||||||

| President of the Government | |||||||||||||

|

• 1975–1976

|

Carlos Arias Navarro | ||||||||||||

|

• 1976–1981

|

Adolfo Suárez | ||||||||||||

|

• 1981–1982

|

Leopoldo Calvo-Sotelo | ||||||||||||

|

• 1982–1996

|

Felipe González | ||||||||||||

|

• 1996–2004

|

José María Aznar | ||||||||||||

| Legislature | Cortes Españolas (until 1977) Cortes Generales (since 1977) |

||||||||||||

| History | |||||||||||||

|

• Established

|

1975 | ||||||||||||

|

• Disestablished

|

2014 | ||||||||||||

| Currency | Peseta (₧, ESP; 1975–2001) Euro (€, EUR; since 2002) |

||||||||||||

| ISO 3166 code | ES | ||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||

The reign of Juan Carlos I of Spain began on November 22, 1975. This was after the death of Francisco Franco, who had ruled Spain as a dictator for many years. Franco had chosen Juan Carlos to be his successor. Juan Carlos became king and promised to follow the laws of the kingdom. His reign ended on June 19, 2014, when he decided to step down. His son, Felipe VI, then became the new king.

Contents

How Spain Became a Democracy (1975–1982)

The first few years of King Juan Carlos I's reign were very important. Spain changed from being a dictatorship to a democracy. This period is known as the transition to democracy. It ended around October 1982, when new elections took place.

Juan Carlos I Becomes King

In 1969, dictator Francisco Franco chose Juan Carlos de Borbón to be the next king. Juan Carlos was then known as the Prince of Spain.

After Franco died in 1975, Juan Carlos became king. He gave a speech where he talked about national unity. He wanted to make changes to the government. This showed he did not want to continue Franco's strict rule.

The first prime minister under the new king was Carlos Arias Navarro. He had also been Franco's last prime minister. Juan Carlos wanted to bring in new people who supported reforms. These included figures like Manuel Fraga and Adolfo Suárez.

Arias Navarro's government aimed for a slow, controlled change towards democracy. This was called "reform in continuity." They wanted to keep some parts of Franco's system. The government did not want to negotiate with the democratic opposition. They also planned to exclude "totalitarian" parties, like the Communist Party, from elections.

Many people, especially students and workers, protested. They demanded freedom and amnesty for political prisoners. There were many strikes, asking for better working conditions and political rights. In March 1976, five people died in Vitoria during police actions against protesters. This event, known as the "Vitoria massacre", made many people realize that Arias's reforms were not enough.

The opposition groups, including the Communist Party, decided to work together. They formed a group called Coordinación Democrática. They demanded a full political amnesty and free elections. They wanted a new constitution to be written.

King Juan Carlos was not happy with Arias Navarro's slow pace. In July 1976, the King asked Arias Navarro to resign. The King then appointed Adolfo Suárez as the new prime minister. Suárez was a "reformist" who had worked under Franco. His appointment surprised many people.

Suárez's First Government (1976–1977)

Adolfo Suárez formed a government of younger reformists. He announced his goal was to make sure future governments were chosen by the Spanish people. He promised free general elections by June of the next year. He also said that the political changes would be put to a public vote.

Suárez's government created the Political Reform Act. This law aimed to create a new parliament with two chambers, elected by all citizens. It also quietly removed all of Franco's old institutions. This meant the law actually ended the old system.

The government also granted an amnesty in July 1976. This freed many political prisoners. However, some prisoners, especially those linked to the Basque group ETA, remained in jail.

Suárez had to convince the Army to accept these changes. He met with military leaders in September 1976. He assured them that the monarchy and Spain's unity would not be questioned. He also promised that "revolutionary" parties, like the Communist Party, would not be legalized. The Army agreed to the reform process under these conditions.

The Political Reform Act was approved by the old Francoist parliament in November 1976. Most members voted for it. Then, a referendum was held on December 15. The government strongly promoted a "YES" vote. The "YES" vote won with 94.2% of the votes. This vote gave the King and his government strong public support for their reforms.

In January 1977, there was a difficult period. Some extreme right-wing groups tried to stop the changes. The 1977 Atocha massacre happened, where lawyers linked to the Communist Party were killed. This event, however, led to more support for the Communist Party. The Army did not intervene, and the government did not declare a state of emergency.

The crisis helped speed up the legalization of political parties. On April 9, 1977, the Communist Party of Spain was legalized. This was a very brave decision by Suárez. Many in the Army were unhappy, but the King supported it. In return, the Communist Party accepted the monarchy and the Spanish flag.

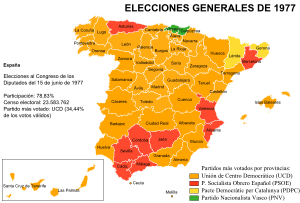

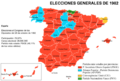

On June 15, 1977, the first free general elections since 1936 were held. There was a very high turnout. Adolfo Suárez's party, Unión de Centro Democrático (UCD), won the most votes but not a full majority. The PSOE came in second, becoming the main left-wing party.

These elections created a new political system. Two large parties, UCD and PSOE, dominated. Other parties, like the Communist Party and Alianza Popular (a conservative party), had less support. In Catalonia and the Basque Country, regional nationalist parties also gained seats.

Suárez's Second Government and the Constitution (1977–1979)

One of the first tasks for the new parliament was to pass a total amnesty law. This law freed all remaining political prisoners. It also meant that no one would be held responsible for actions during Franco's dictatorship. This was seen as a "pact of forgetting" to help Spain move forward.

Spain also faced an economic crisis. The government and political parties signed the Moncloa Pacts in October 1977. These agreements helped stabilize the economy and control rising prices. They also increased social spending on things like unemployment benefits and pensions.

Another important issue was the "regional question." Catalonia and the Basque Country wanted more self-government. The government gave them "pre-autonomy" status. This meant they could start setting up their own regional governments. This also encouraged other regions to ask for more self-rule.

The most important task was writing a new Constitution. A special committee was formed with members from different parties. They worked to create a document that everyone could agree on. The Socialists and Communists agreed to accept the monarchy, as long as the King's powers were limited.

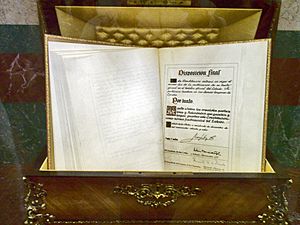

The new Constitution was approved by parliament on October 31, 1978. It received strong support from most parties. On December 6, 1978, the Constitution was put to a referendum. It was approved by 88% of voters. In the Basque Country, fewer people voted "YES" due to a campaign for abstention.

Suárez's Third Government and the 23-F Coup (1979–1981)

After the Constitution was approved, Suárez called new elections in 1979. UCD won again, but still without a full majority. The PSOE did not gain much ground.

Soon after, the first local elections since the 1930s were held. Left-wing parties won in many major cities. For example, socialists became mayors of Madrid and Barcelona.

The government also worked on the "autonomous" issue. They negotiated new self-government laws for the Basque Country and Catalonia. These laws, called Statutes of Autonomy, gave them more powers. Both were approved by referendums in October 1979. This led to the creation of their own parliaments and regional governments.

However, the UCD party started to face problems. The economy worsened, and ETA terrorism increased. Many people felt disappointed with politics. Adolfo Suárez's government faced internal divisions. In January 1981, Suárez announced his resignation as prime minister.

On February 23, 1981, during the vote for a new prime minister, a group of armed civil guards stormed the Spanish parliament. This was an attempted coup d'état. At the same time, a general in Valencia declared a "state of war" and sent tanks into the streets.

King Juan Carlos I played a crucial role in stopping the coup. He ordered all military leaders to stay in their barracks. In the early morning of February 24, the King appeared on television, dressed in his military uniform. He condemned the coup and defended democracy. This speech was key to defeating the coup. The coup leaders surrendered, and the government and deputies were freed.

Calvo Sotelo's Government (1981–1982)

After the coup attempt, Leopoldo Calvo Sotelo became the new prime minister. His government worked with the PSOE to strengthen democracy. They passed a law to prevent future coup attempts. They also worked on organizing the self-governing regions.

Calvo Sotelo's government decided to apply for Spain's membership in NATO (North Atlantic Treaty Organization). This was approved by parliament in October 1981. However, the PSOE promised to hold a referendum on NATO membership if they came to power.

The UCD party continued to struggle with internal problems. Many members left the party. Facing a weakened party, Calvo Sotelo called new general elections in August 1982.

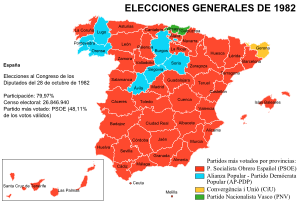

In the 1982 elections, the PSOE won a huge victory. They gained a full majority in parliament. The People's Party (a new name for Alianza Popular) became the main opposition party. The UCD party almost disappeared.

These elections were a big moment for Spain. They showed that citizens supported democracy. For the first time, a party that had been against Franco's regime came to power. This marked the end of Spain's transition to democracy.

Felipe González's Socialist Government (1982–1996)

After their big win in 1982, the PSOE, led by Felipe González, governed Spain for almost 14 years. They won elections in 1986 and 1989 with full majorities. From 1993, they continued to govern with support from other parties. During this time, Spain's democracy became very strong.

Making Democracy Stronger

The socialist government focused on making democracy stable. They wanted to end military coup threats and terrorism. They made the Army more professional and under civilian control. This helped stop any future coup attempts.

Against terrorism, the government tried to reintegrate imprisoned terrorists who rejected violence. However, there were also secret "dirty war" actions against ETA, known as the GAL. These actions caused many deaths.

The government also tried to negotiate with ETA leaders, but talks failed. ETA continued its attacks, some of them very deadly. In response, the main political parties signed an anti-terrorist pact in 1988.

The government also worked to develop rights and freedoms. They passed laws for education, recognizing private schools and giving universities more freedom. They also passed laws on Habeas corpus, freedom of assembly, and trade union freedom.

Regarding regional self-government, more autonomy statutes were approved. Public spending was decentralized, giving more power to the regions. However, Catalonia and the Basque Country continued to ask for even more self-rule.

Joining Europe and NATO

The socialists wanted Spain to be fully part of Europe. Negotiations for Spain to join the European Economic Community (EEC) had been slow. But with a new socialist president in France, progress was made. On January 1, 1986, Spain joined the EEC, along with Portugal.

After joining the EEC, it was time for the promised referendum on Spain's membership in NATO. Felipe González's government decided to support staying in NATO. They set three conditions: no joining the military structure, no nuclear weapons in Spain, and fewer US military bases.

Many people, especially from the left, opposed NATO membership. But Felipe González campaigned strongly for a "YES" vote. He even said he would resign if "NO" won. On March 12, 1986, the "YES" vote won by a small margin. This strengthened González's leadership.

Social Policies and the Economy

During the socialist period, Spain developed a strong welfare state, similar to other European countries. Healthcare and education were made available to everyone. Spending on pensions and unemployment benefits also increased a lot. This was possible because the government increased taxes.

The economy also grew strongly from 1985 to 1992. However, there was also an increase in speculative investments.

The government's economic policies led to disagreements with the main trade unions, especially UGT. The government focused on controlling prices and making the job market more flexible. This led to more temporary jobs.

The unions felt the government was not following the socialist program. In 1985, UGT leader Nicolás Redondo voted against a pension law. The disagreements grew, leading to a major general strike on December 14, 1988. The strike was very successful and paralyzed the country.

Socialist Decline (1989–1996)

Felipe González called elections in October 1989. The PSOE won again, but with a smaller majority. The People's Party (PP), led by José María Aznar, gained more seats.

During this period, several corruption scandals affected the PSOE government. One famous case was the "Guerra case", involving the vice-president's brother. Another was the "Filesa case", which involved the party's funding. These scandals damaged public trust in the government.

In 1992, Spain hosted two major events: the 1992 Summer Olympics in Barcelona and the Seville Expo. These events helped show Spain as a modern country. Spain also played a bigger role in international affairs, like hosting the Middle East Peace Conference.

However, a strong economic recession began in 1992. Unemployment rose sharply, reaching 3.5 million people. This led to another general strike. The economic problems and scandals led Felipe González to call early elections in June 1993.

In the 1993 elections, the PSOE won again, but without a full majority. They had to rely on support from Catalan and Basque nationalist parties. The government continued to face economic challenges and more scandals.

In the European Parliament elections of 1994, the People's Party won more votes than the PSOE for the first time. This led them to demand new general elections.

As more scandals came out, the Catalan nationalist party CiU withdrew its support for the government. This left the PSOE in a minority. Felipe González had to call general elections for March 1996. The People's Party won these elections, ending the PSOE's 14 years in power.

Aznar's Popular Party Government (1996–2004)

The People's Party (PP) governed Spain for eight years under José María Aznar. In his first term (1996–2000), the PP needed support from Catalan nationalists. But in his second term (2000–2004), they won a full majority.

Economy and Social Changes

The PP government focused on improving the economy. They privatized public companies like Telefónica and Repsol. They also worked to reduce government spending and control prices. A key goal was to meet the requirements to adopt the new European currency, the euro.

These policies were successful. The Spanish economy grew strongly, unemployment decreased, and prices were low. In 1998, Spain joined the group of countries that adopted the euro. Euro banknotes and coins started circulating on January 1, 2002.

However, this strong economic growth also led to a "property bubble." Many people bought houses not to live in them, but as an investment. This made housing very expensive, especially for young people.

The government also maintained social spending on education, health, and pensions. They reaffirmed the Toledo Pact on pensions, ensuring their revaluation.

Anti-Terrorism and Regional Issues

The PP government adopted a new approach to fighting ETA terrorism. They believed that only police action could end ETA. They said the only "dialogue" with ETA would be for them to surrender their weapons.

ETA announced a truce in 1998, but the government saw it as a trick. In November 1999, ETA broke the truce and resumed attacks. The PP and PSOE then signed an Antiterrorist Pact. This pact, along with legal actions against Batasuna (ETA's political wing), weakened ETA.

However, tensions between "nationalists" and "constitutionalists" in the Basque Country continued. The PP government proposed making Herri Batasuna illegal. A new Law of Political Parties was passed. In 2003, the Supreme Court declared Batasuna illegal, calling it ETA's "political arm."

In Catalonia, a new left-wing government was formed in 2003. This government, which included a pro-independence party, caused tension with the central government. In early 2004, it was revealed that a Catalan leader had met with ETA. ETA then declared a truce "only for Catalonia."

Foreign Policy Changes

Aznar's government wanted Spain to be more involved in international actions. They decided to create an exclusively professional army, ending compulsory military service.

The PP government also aligned Spain more closely with the United States. This was seen in their European policy. They also had strained relations with Morocco, especially over the Perejil Island incident in 2002.

Spain strongly supported the "war against terrorism" declared by US President George W. Bush after the September 11 attacks. Spain supported the Afghanistan war and the Iraq War in 2003, even though most Spanish people were against the Iraq War. The government sent troops to Iraq after the invasion.

11-M Bombings and 2004 Elections

On March 11, 2004, three days before the general elections, the 11-M bombings happened in Madrid. Ten bombs exploded on commuter trains, killing 191 people and injuring over 1,500. It was the largest terrorist attack in Spanish history.

Initially, the government said ETA was responsible. However, police investigations soon pointed to Islamist terrorism linked to Al-Qaeda. The government continued to suggest ETA was the main suspect. This caused confusion and anger among the public.

On the day before the elections, thousands protested in front of PP offices. They accused the government of "hiding the truth." The government then announced arrests of Moroccans and the discovery of a video claiming responsibility for Al-Qaeda.

On Sunday, March 14, 2004, the general elections were held. The PSOE won, gaining more seats than the PP. A month later, José Luis Rodríguez Zapatero became the new prime minister.

Zapatero's Socialist Government (2004–2011)

Zapatero's socialist government lasted for two terms. The first (2004–2008) was a time of many changes. The second (2008–2011) was dominated by an economic crisis.

Years of Change (2004–2008)

One of Zapatero's first decisions was to withdraw Spanish troops from Iraq. This fulfilled an election promise. Spain also became closer to Germany and France. The European Constitution was signed in 2004. Spain held a referendum on it in 2005, which was approved, but many people did not vote.

The People's Party accused the government of winning the elections unfairly due to "manipulation" after the 11-M attacks.

Zapatero's government introduced several legal reforms to expand citizens' rights. These included laws recognizing same-sex marriage, "express divorce", and promoting equality for women. They also passed the Historical Memory Law, which recognized victims of the Civil War and Franco's regime. These reforms faced strong opposition from the PP and conservative groups.

In Catalonia, the regional parliament approved a new Statute of Autonomy in 2005. It called Catalonia a "nation." This was criticized by the PP, who said it went against the Spanish Constitution. After negotiations, a modified version was approved in a referendum in 2006.

Regarding the Basque Country, Zapatero said he was willing to "dialogue" with ETA to end terrorism. In March 2006, ETA announced a "permanent ceasefire." The PP accused the government of giving in to ETA. Many demonstrations were held against negotiations with ETA.

However, on December 30, 2006, ETA placed a powerful bomb at Barajas airport, killing two people. The government then suspended the "peace process." ETA ended the truce in June 2007 and resumed attacks.

The Spanish economy was growing well when Zapatero took office. Many immigrants arrived in Spain, boosting the economy. The government regularized many undocumented immigrants.

However, in 2007, the "property bubble" began to burst. Housing prices stopped rising, and the construction sector slowed down. This led to an increase in unemployment. The economy became the main topic of debate for the 2008 general election.

Years of Crisis (2008–2011)

The PSOE won the general election in March 2008, but still without a full majority. Zapatero was re-elected prime minister.

The economic situation worsened significantly from September 2008 due to the global financial crisis. Unemployment soared, especially in construction. The government responded with economic stimulus plans, but the economy continued to shrink. Unemployment reached over 20% of the working population.

The government's spending to stimulate the economy led to a large public deficit. The finance minister, Pedro Solbes, wanted to cut spending, but Zapatero disagreed. Solbes left the government.

The crisis also affected Spanish banks, especially savings banks, which had lent a lot of money to construction companies. The government had to provide public money to help them.

In 2010, the European debt crisis began, affecting Spain. European countries demanded that Spain reduce its public spending. In May 2010, Zapatero announced drastic cuts in public spending. This included reducing civil servants' salaries and freezing pensions. These measures caused a new recession and increased unemployment.

The government also introduced "structural reforms," like a new Labor Reform and raising the retirement age. These policies led to a break with the trade unions, who called a general strike in September 2010.

Despite these measures, Spain's debt problems continued. In 2011, the European Central Bank intervened to buy Spanish debt. In return, they demanded more reforms. Zapatero's government quickly reformed the Constitution to limit public deficit.

The economic crisis led to a political crisis. Public trust in politicians and institutions fell. There were also many corruption scandals involving both major parties and even the Royal House. The King's son-in-law, Iñaki Urdangarin, was investigated in a case that damaged the monarchy's image.

The PSOE's popularity dropped in elections. In April 2011, Zapatero announced he would not run in the next general elections. The PSOE suffered a major defeat in the municipal and regional elections in May 2011.

On May 15, 2011, protests of "outraged" people, mostly young, began in Spanish cities. They camped in public squares, like the Puerta del Sol in Madrid. This movement, known as the 15-M movement, criticized political parties and demanded real democracy.

Another major issue was the growth of the independence movement in Catalonia. This followed a court ruling in 2010 that limited parts of the Catalan Statute of Autonomy. A large demonstration for independence was held in Barcelona in July 2010.

In the Basque Country, ETA announced the definitive end of its "armed struggle" on October 20, 2011. This opened a new political chapter in the region.

Rajoy's Popular Party Government (2011–2014)

Facing low support, Zapatero called early general elections for November 2011. The People's Party won a full majority, their best result ever. The PSOE had its worst result. Mariano Rajoy became the new prime minister.

Economic Crisis and Protests

Rajoy's government immediately focused on reducing public spending to control the budget deficit. They continued the previous government's austerity policies. The most important reform was the Labor Reform in February 2012. This reform was rejected by unions, leading to a general strike in March 2012.

The government cut public spending in many areas, like civil servants' salaries and social benefits. They also increased taxes, despite promising not to. These policies caused a second recession, and unemployment continued to rise. By March 2013, unemployment reached a record 27.1%.

In April 2012, the government announced more cuts in education and healthcare. This led to a general education strike in May 2012.

The Spanish banking system also faced problems. Many banks needed public money to recover. In June 2012, Spain asked the European Union for a financial rescue of up to 100 billion euros to help its banks.

The government's harsh policies did not immediately stop the rise in Spain's borrowing costs. In July 2012, it seemed Spain might need a full bailout. However, the president of the European Central Bank, Mario Draghi, promised to do "everything necessary" to save the euro. This helped calm the financial markets.

Catalonia's Challenge and Political Crisis

Another major challenge for Rajoy's government was the growing independence movement in Catalonia. A large demonstration for independence was held in Barcelona in September 2012. The Catalan parliament then approved a "Declaration of Sovereignty" in January 2013.

In September 2013, a huge human chain, called the "Catalan Way towards Independence", was formed across Catalonia. The Catalan parties agreed to hold a "consultation" (referendum) on independence in November 2014. However, the Spanish parliament rejected the request to hold this referendum.

The economic crisis also led to a general political crisis. Public satisfaction with democracy fell sharply. Many political institutions, including parties and unions, received very low ratings. The monarchy's image also suffered.

In the European Parliament elections in May 2014, the two main parties, PP and PSOE, lost a lot of support. Smaller parties, and a new party called Podemos, gained many votes. This showed a big shift in Spanish politics.

King Juan Carlos I Steps Down

The King's son-in-law, Iñaki Urdangarin, was involved in a corruption scandal known as the Nóos case. This greatly damaged the monarchy's image. In December 2011, the Royal House removed Urdangarin from official events. The King himself spoke about "justice being equal for all." Urdangarin was later charged and had to testify in court.

Another blow to the King's image came in April 2012. It was revealed that he had broken his hip during an elephant hunt in Botswana. This caused a big controversy. The King publicly apologized, saying, "I am very sorry. I made a mistake and it won't happen again."

The King had several more hip operations. In January 2014, he appeared tired at an official event. Soon after, his daughter, Infanta Cristina, was also charged in the Nóos case. This further hurt the monarchy's popularity.

On Monday, June 2, 2014, Juan Carlos I announced that he would step down as king. He had made this decision months earlier.

The same day, rallies were held in several cities, calling for a referendum to decide if Spain should remain a monarchy or become a republic. This idea was also debated in parliament when the law for the King's abdication was discussed. The law was approved by a large majority of deputies.

On June 18, King Juan Carlos signed the law, which was his last official act. The next day, his son, Felipe VI, was proclaimed King of Spain.

Images for kids

-

The Prince of Spain Juan Carlos de Borbón in 1971.

-

Manuel Fraga Iribarne, a key minister in Arias Navarro's government.

-

Palace of Moncloa, seat of the Presidency of the Spanish Government since 1976.

-

The new Constitution.

-

Leopoldo Calvo Sotelo (1976).

-

Blast furnace number two of the dismantled Altos Hornos del Mediterráneo in Sagunto.

-

Nicolás Redondo and Marcelino Camacho, leaders of General Union of Workers and Workers' Commissions respectively ─ the two major trade union confederations that organized the general strike of "14-D" ─ during an act of homage to the political prisoners of the Francoism in 2008.

-

Felipe González with the President of the Council of Ministers of Italy, Giuliano Amato, at the beginning of the Spanish-Italian Summit (March 3, 1993).

-

José María Aznar with US President George W. Bush at the Summit of las Azores on March 17, 2003, at which the ultimatum that initiated the Iraq War was given to Saddam Hussein.

-

First government of José Luis Rodríguez Zapatero, April 2004.

-

Elena Salgado, new Minister of Economy and Finance as of April 2009, replacing Pedro Solbes.

-

Mariano Rajoy, three weeks after winning the elections.

-

The president Artur Mas and the leader of ERC Oriol Junqueras sign on December 19, 2012, an Acord per a la transició nacional (or Pacte per la Llibertat) committing to convene a consultation so that the "people of Catalonia" can decide whether they want to become a "new State in Europe".

See also

In Spanish: Reinado de Juan Carlos I de España para niños

In Spanish: Reinado de Juan Carlos I de España para niños

| Selma Burke |

| Pauline Powell Burns |

| Frederick J. Brown |

| Robert Blackburn |